Uncategorized

Every bit of help is welcome when controlling exotic species—at least we have a few exotics eating others. Domestic cats are obvious predatory exotics here in BC, whether they’re fattened pets out prowling for even more food or feral and eating just to survive.

Domestic chickens (Gallus gallus) also eat whatever they can catch, so any stray lizard wandering into a chicken run had better run really fast. Do chickens care if wall lizards taste like chicken?

House sparrows (Passer domesticus) are known to eat hatchling common wall lizards (Podarcis muralis), and now we can add the European starling (Sturnus vulgaris) to the list of exotic species eating common wall lizards too.

This European starling has a taste for exotic food, photographed by Jeremy Gatten, May 30, 2018, in Central Saanich.

Now I find myself in a funny spot. I like lizards, but I don’t like invasive species. Yet I find myself rooting for an invasive species because it is eating wall lizards.

The Early Bird post

Many photos have circulated in the last year showing an American kestrel feeding on common wall lizards. It is so nice to see a predator with a taste for exotic food.

But falcons aren’t the only lizard predators out there. Young lizards are taken by a wide range of animals, from spiders—yes, hatchling lizards get caught in webs and eaten by spiders—and snakes to raccoons, domestic cats and dogs, some larger birds like the great blue heron, and a wide range of perching birds.

American robin with a fast-food snack. Photo courtesy of Kathy Lamb.

This weekend I received a nice photo of an American robin who has also decided that young wall lizards are fast food worth the effort.

Spotted towhee with a sizable saurian snack. Photo courtesy of Jenny Whitfield.

Spotted towhees, house sparrows, dark-eyed juncos, Steller’s jays and a few other birds also love lizard lunches. But even with passerine predation, the wall lizard population is still beyond control.

American robin and its tetrapod treat. Photo courtesy of Kathy Lamb.

If you see something hunting and catching common wall lizards, please take photos and document the event. Records can be added to iNaturalist and emailed to me at the Royal BC Museum.

The Yard Birds post

Why wouldn’t you want a garden full of birds and their songs? My city garden is alive with birds—not rock pigeons, European starlings and house sparrows, but species native to this region.

Anna’s hummingbirds, golden-crowned sparrows, dark-eyed juncos, bushtits, bewick’s wrens, spotted towhees, American robins, Cooper’s hawks, merlins . . . the list goes on. A savannah sparrow spent a few sheltered days in our garden recuperating after a window strike. The long grass and other plants gave it plenty of shelter from predatory eyes.

Forget grass—go for complexity.

Small trees, bushes and ground cover all make a multilayered environment that is great habitat for a range of birds. Plant flowers for pollinating insects. Leave debris on the ground to provide shelter for other arthropods and prevent rain compaction of the soil.

The more complex the ground cover, the less you may need to water—the soil itself will be shielded from direct sunlight and will keep moist. If you are lucky, toads and salamanders will move in.

Cultivate seed-bearing plants that birds can harvest in addition to plants that you can enjoy, both visually and on the dinner table. In our garden, there is a fair degree of sharing with our avian neighbours. Our thornless blackberries, kale flowers and borage are a hit with the house finches.

Have a look at this video series. Obviously, based on the birds (cardinals—wow!), this is from eastern Canada (Ontario). The closest comparisons I have seen in my garden to the bold colours of a cardinal are a western tanager and northern oriole.

The same garden design principles apply everywhere—complexity, minimum disturbance, a water source(?). Wherever you are in North America, you can have a garden full of birds, colour, song and natural entertainment.

Fishy Photo post

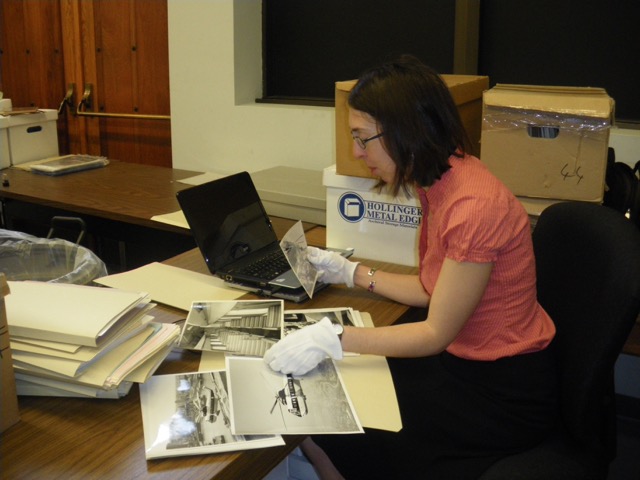

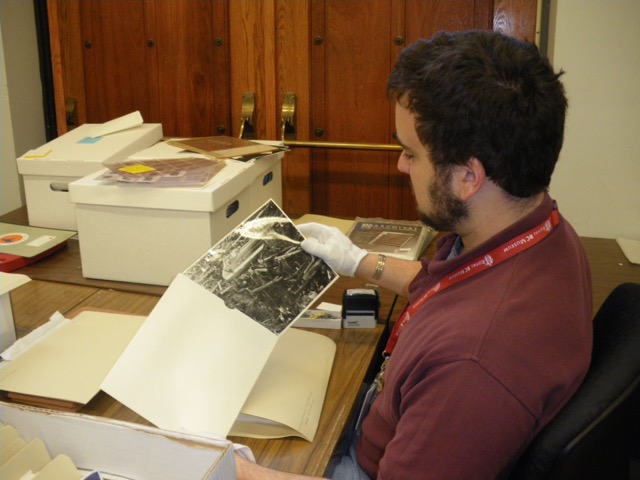

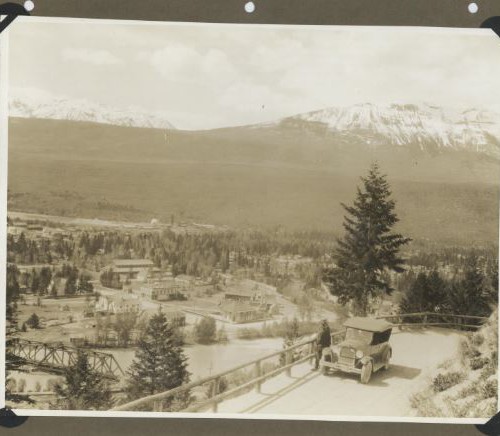

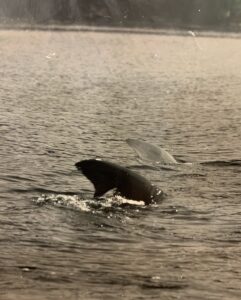

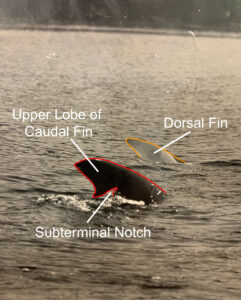

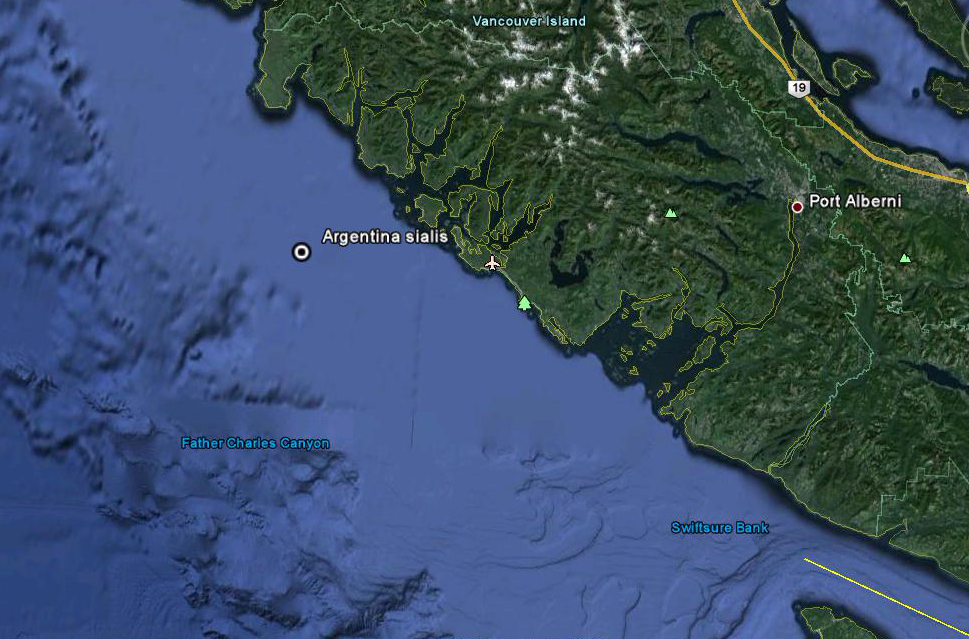

While cleaning out files for the move of our offices (and the entire Royal BC Museum collection), I found an old black and white photograph. Most photos I have found are not useful given today’s publication standards. But this black and white photo by Barry Campbell, taken September 8, 1975, shows a basking shark off the north end of Flores Island, not far from Obstruction Island, along the west side of Vancouver Island.

The photographer said he had seen up to eight sharks at a time in this area—I can’t imagine seeing eight of the planet’s second largest shark. This species has been all but eliminated from British Columbia. Seeing one is newsworthy today; if someone said they’d seen eight, I would not believe them.

There is another note attached to the photograph, dating to 2002. The author of this newer note states that the fins are from a dolphin or some other whale. However, the photo clearly shows the shark swimming away from the photographer with the tail in the foreground, and further away is the dorsal fin flopped over to the left. The subterminal notch in the tail, which delineates the upper lobe, is clearly visible. The dorsal seems to be lighter coloured, but this could simply be the angle light is hitting the dorsal fin at relative to the tail. The shark was estimated to be about 7.6 metres long (back then he used the old measurement of feet, and this shark was about 25 of those).

I wasn’t fortunate enough to be on the CCGS Vector the year they saw a basking shark up near Langara Island, but someday I hope to see one of these massive plankton predators in person.

Anoles Appear post

Our garden centres carry tropical plants as well as temperate plants for your garden. Even hardware stores like Canadian Tire, Rona, Lowes and Home Depot carry a fair selection of plants. Indoor plants often come from way south of Vancouver Island, and in the last few years, there has been a noticeable increase in people reporting the presence of stow-away lizards—usually the brown anole (Anolis sagrei). In the southern USA, the brown anole is at a population density such that accidental transport is commonplace, even expected.

In 2020, I received several emails about brown anoles in plants bought from stores in BC. The appearance of lizards as stowaways likely is not new, but people’s awareness of exotic and potentially invasive species has certainly improved. The lizards generally appear as hatchlings, after being shuttled north of the international border as single eggs in potting soil.

These days, people can easily report the strange things that crawl out of their new house plants. Records are added to iNaturalist to document the trade in plants as a vector for herpetile dispersal. We even received a cuban treefrog (RBCM 2541) in August 2020, caught at a Rona outlet in Nanaimo. While these are not “wild” records in the strict sense in iNaturalist, they are important records of assisted dispersal.

In 2020, a male brown anole appeared in Duncan on Vancouver Island in a plant bought at the Canadian Tire outlet in that city. The record is in iNaturalist. This one was small, but not a hatchling as I had suspected. I had assumed lizards arrive as eggs, deposited one at a time in the soil in plant pots. This male was thin, and it could have been in Canadian Tire in Duncan for some time. Once it was caught, it was fed and housed in luxury accommodations, and now has been dropped off to keep me company.

Brown anoles have variable thermal tolerance, with those ranging further north having a lower critical thermal minimum. In other words, those which invaded northern regions have evolved tolerance for cooler temperatures—not bad for a species originating in the Caribbean. I wonder when climate change and a warming BC coast will intersect with the minimum temperatures needed for brown anole survival? I bet they can already survive here in a greenhouse or garden centre with some measure of climate control.

Because of the cold snap in the USA in 2021 and previous polar vortex events, there was strong selection for cold-tolerant lizards. We now know of anoles that can survive down to 4.4C (Stroud et al. 2020). This means that future stowaways may come from cold-hardy stock, assuming cold tolerance is persistent as a new trait. Tolerance of colder temperatures increases the chance brown anoles could survive here in southwestern BC in the right location. The rest of Canada still is too cold to support anoles outside of a cozy warm greenhouse.

Brown Anoles are native to Cuba, the Bahamas and satellite islands, but they have become globe-hopping invaders, with a significant track record of establishment and spread in the USA since the first appearance in the Florida Keys (Garman 1887, in Lever 2003).

Kraus (2009) and Lever (2003) lists the following transport vectors for brown anoles, with additions by me based on iNaturalist records where the source of the lizard was specified (Canadian records in red):

Pet Trade: Canary Islands and all Hawaiian Islands.

Cargo stow away: St. Vincent, Grenada, Ontario, and the US states of Maine, Florida, Georgia, Texas, Pennsylvania, Alabama, Arkansas and Louisiana.

Intentional release: Florida

Unknown: Mexico, Belize, Bermuda, and the US state of South Carolina.

Nursery Trade: Cayman Islands, Taiwan, British Columbia, Alberta, Ontario, and the US states of Florida, Georgia, Texas, California, Arizona, Colorado, Vermont, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, New York, Delaware, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Michigan, Iowa, Kentucky, Indiana, Wisconsin, Mississippi, Illinois, Kansas, Oklahoma, Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, Ohio, South Dakota, Tennessee, Washington and Virginia.

Clearly the trade in ornamental plants is the biggest source of brown anoles, and we can expect more of these exotic lizards in the future. Fortunately they tend to ship one at a time, are unlikely to find mates, and records in iNaturalist across most of the United States represent single lizards, not established populations. But don’t be surprised if you shop at a nursery someday and see these guys flitting about in search of insects. If a male and female do end up in the same greenhouse, and there are plenty of plants where eggs can be deposited, a population could easily become established. Their colonization pattern is almost like our own, surviving in a biosphere, waiting for the rest of a planet to be terraformed. But in this case, lizards only have to wait for climate warming to give them the chance at freedom.

References: Kraus 2009. Lever 2003.

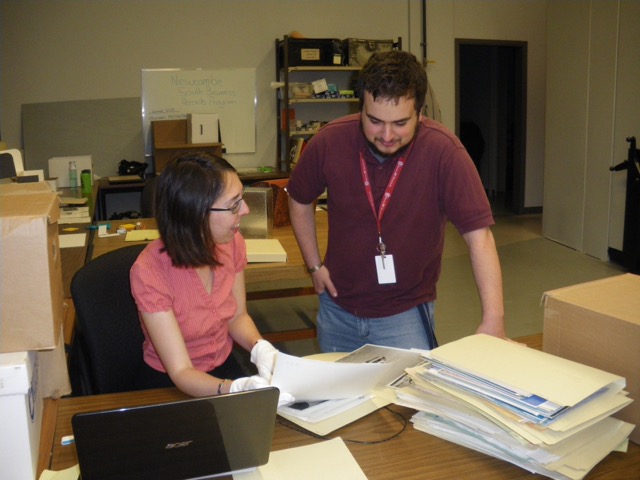

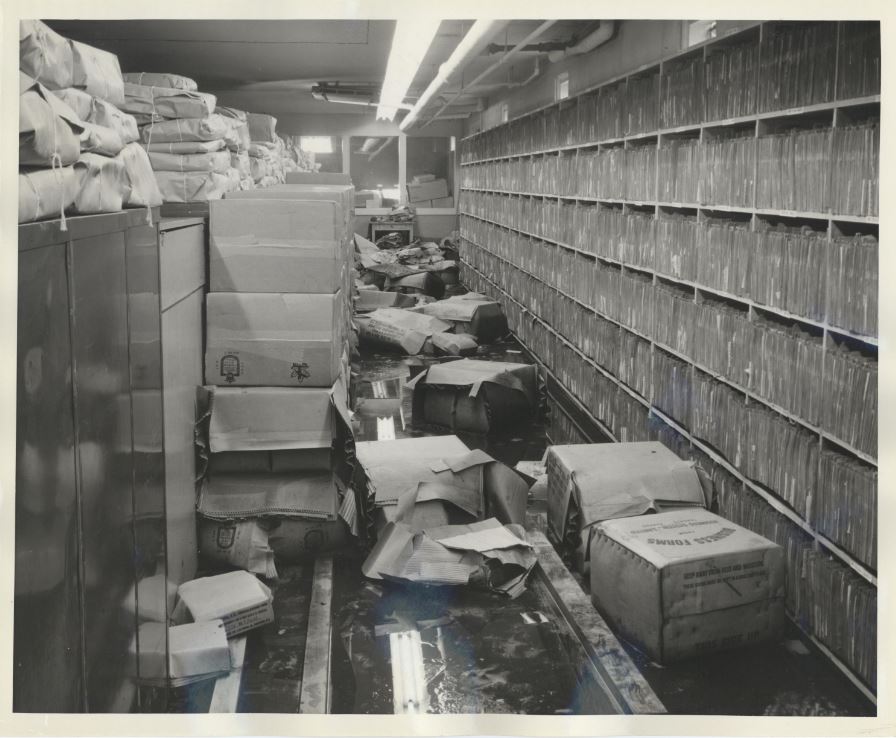

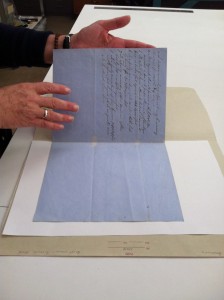

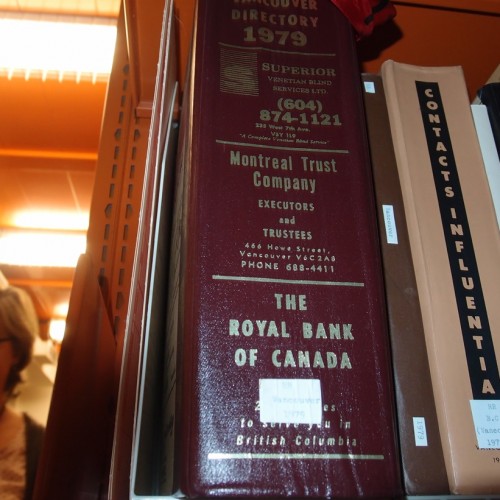

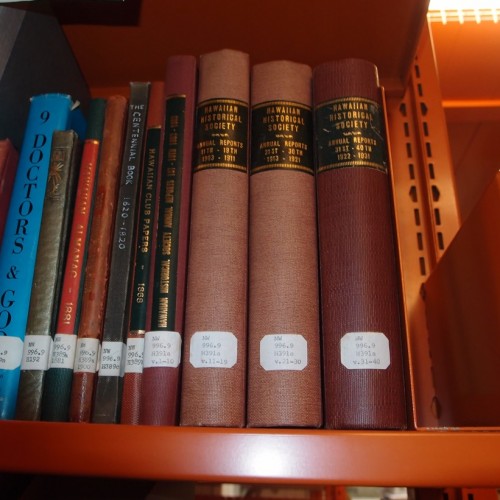

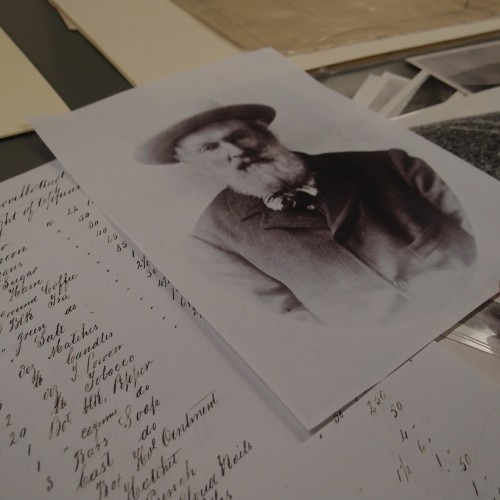

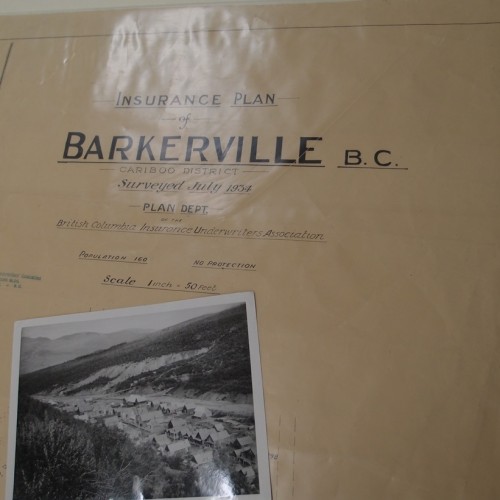

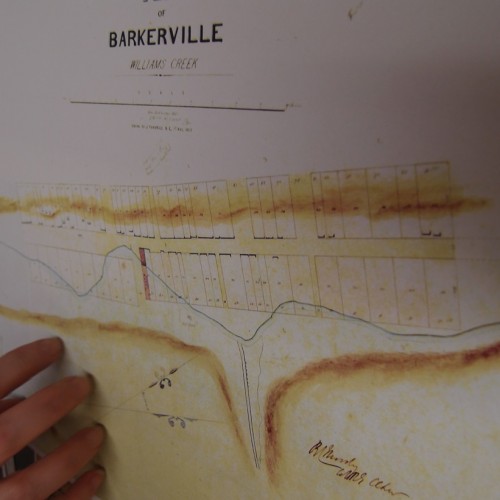

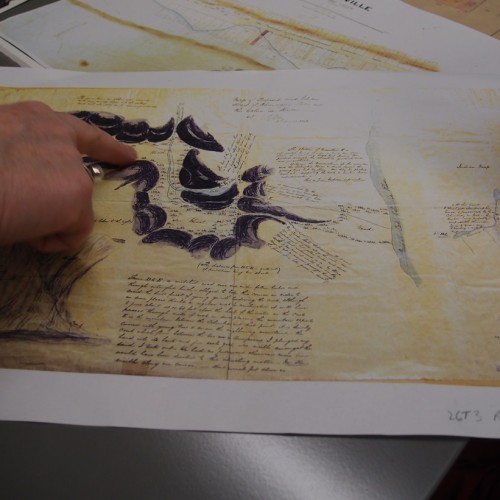

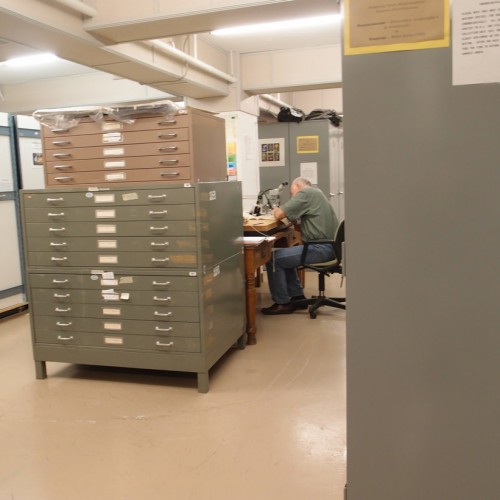

The Royal BC Museum and BC Archives are preparing collections for a move to the new Collections and Research Building that will be constructed in Colwood in 2024 (see the announcement in Victoria News). This process involves surveying collections, re-housing items that may not currently be housed with enough protection for transportation outside of the storage areas and conserving artifacts and records that are not stable enough to be moved.

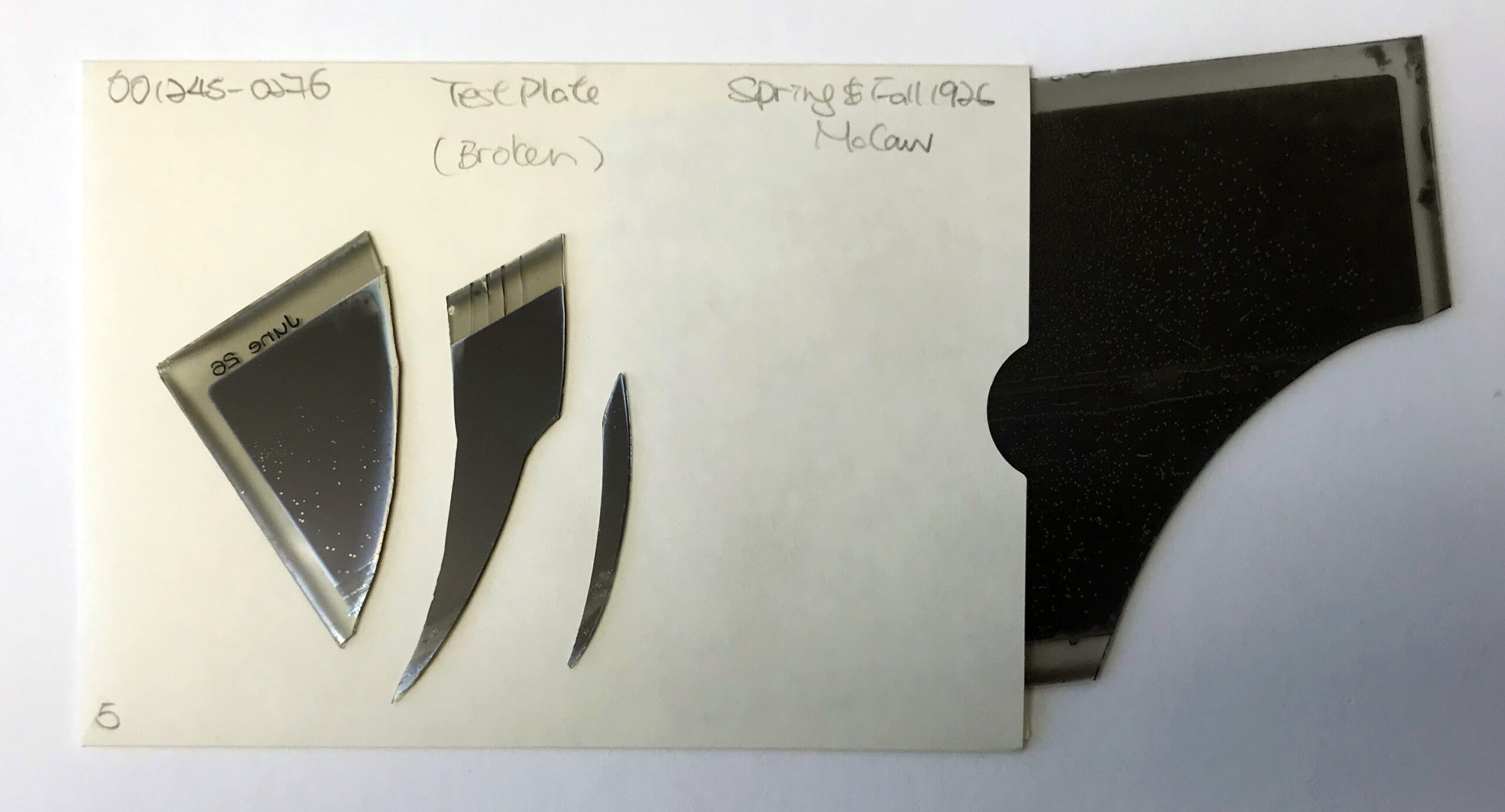

The Issue of Broken Glass Plates

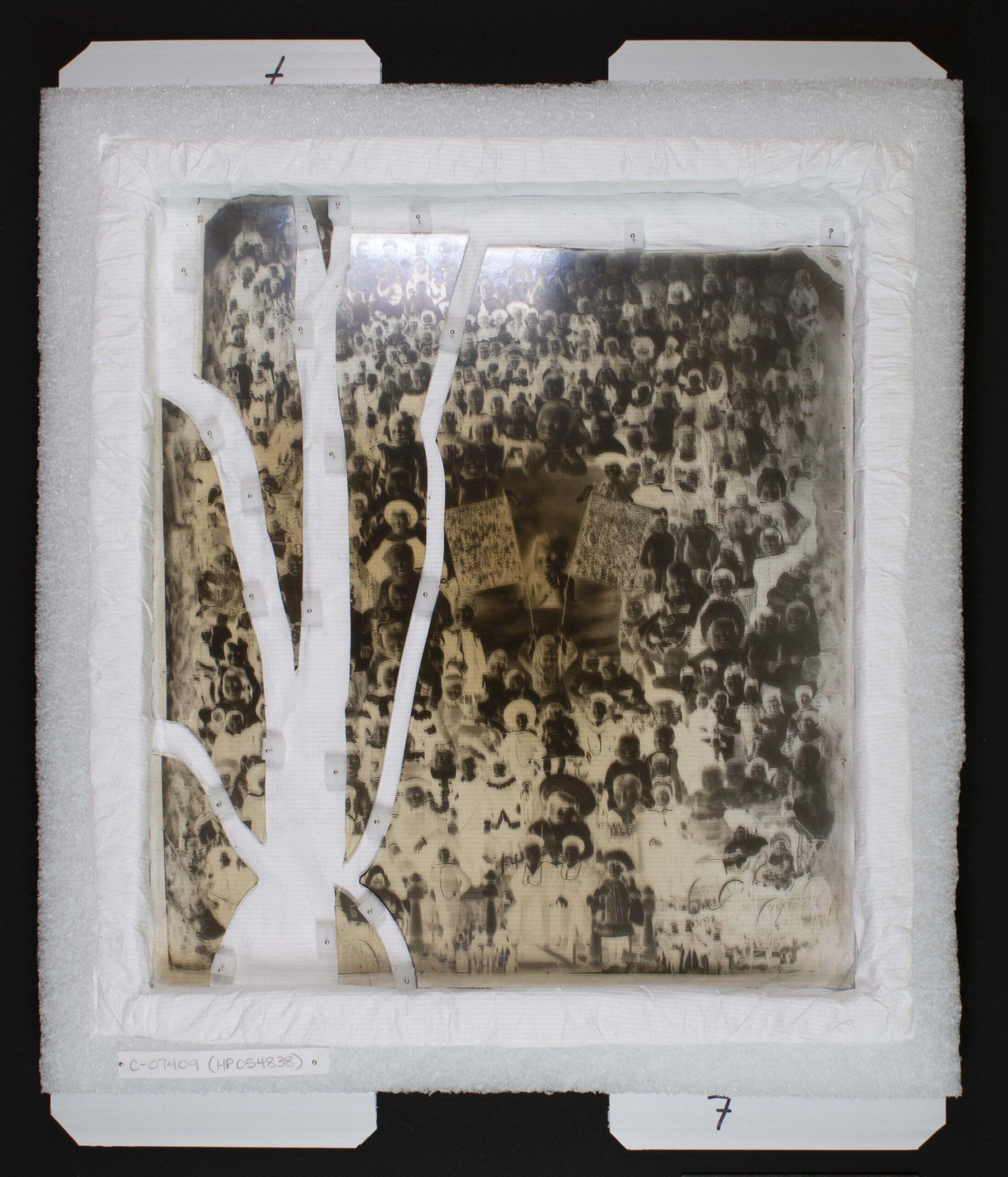

One thing that has come through the Paper Conservation Lab a lot is broken glass-plate photographs. Glass plates were used as a support for photographic slides and negatives early in the history of photography and continued to be used well into the first half of the twentieth century. Many have undergone treatment in the past couple of years (see my previous blog post, Fragments of Glass: Repairing a WWI Glass Plate Negative), but these treatments are time-consuming. Too time-consuming for the size of the backlog measured against the staff resources currently available. This means that some plates may need to be moved prior to being treated. How do you move sharp, fragile shards of glass-plate photographs in a manner that keeps the plates and those handling them safe, while also maintaining the intellectual links these plates have to the rest of their respective collections?

The solution must account for plates of varying sizes that currently exist in two or more shards of varying sizes. All of the shards will need to be kept together so that pieces don’t get lost, and each shard should be secured in place to prevent shuffling during transit. Many broken plates are currently stored in envelopes. In these cases, the individual pieces have been permitted to grind up against each other and move around, creating an opportunity for the sharp edges of the glass to cut up the delicate photographic emulsion layer–a situation that would only become exacerbated by the vibrations associated with a move. It has also led to some shards becoming shuffled and mixed up.

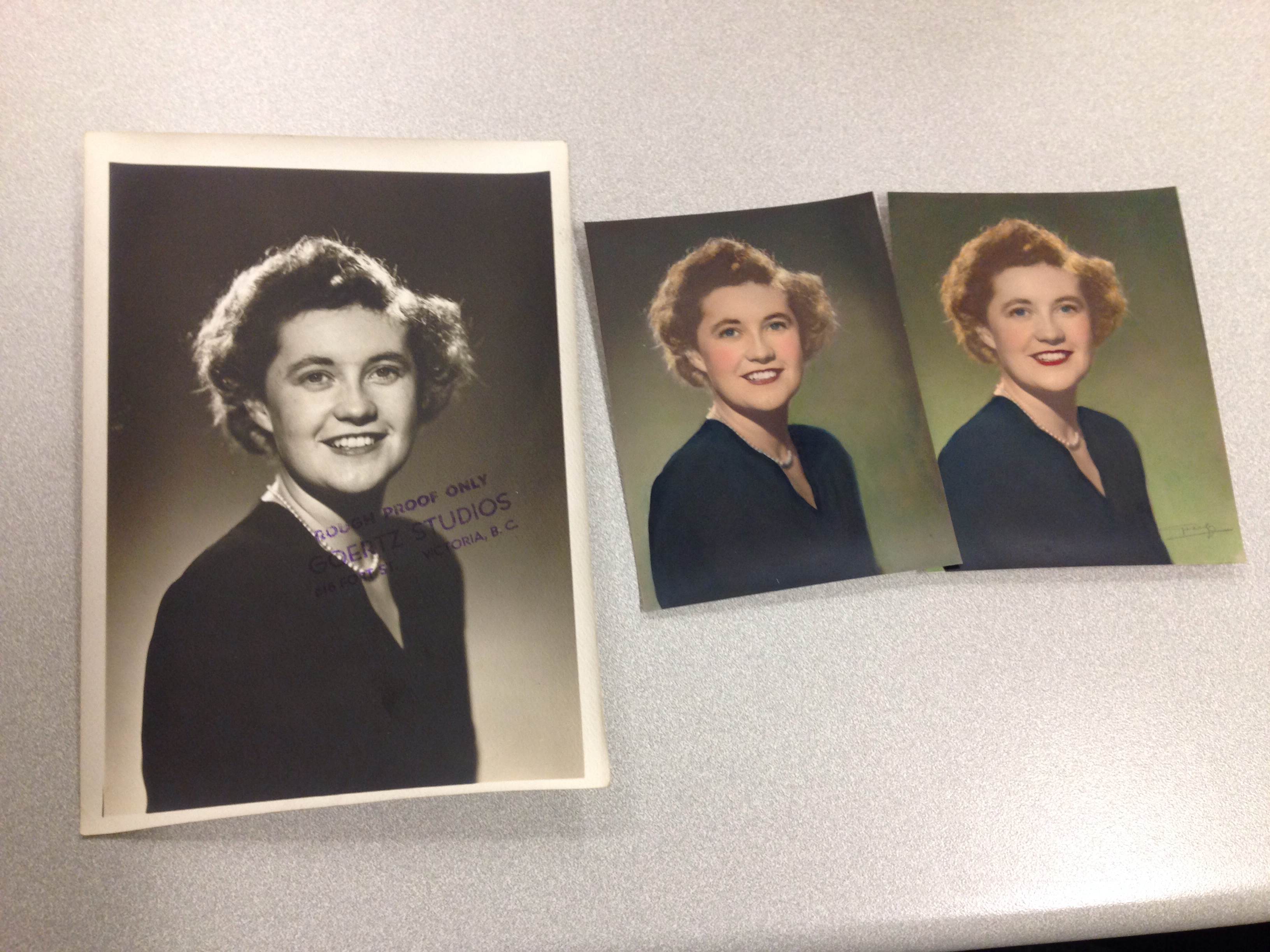

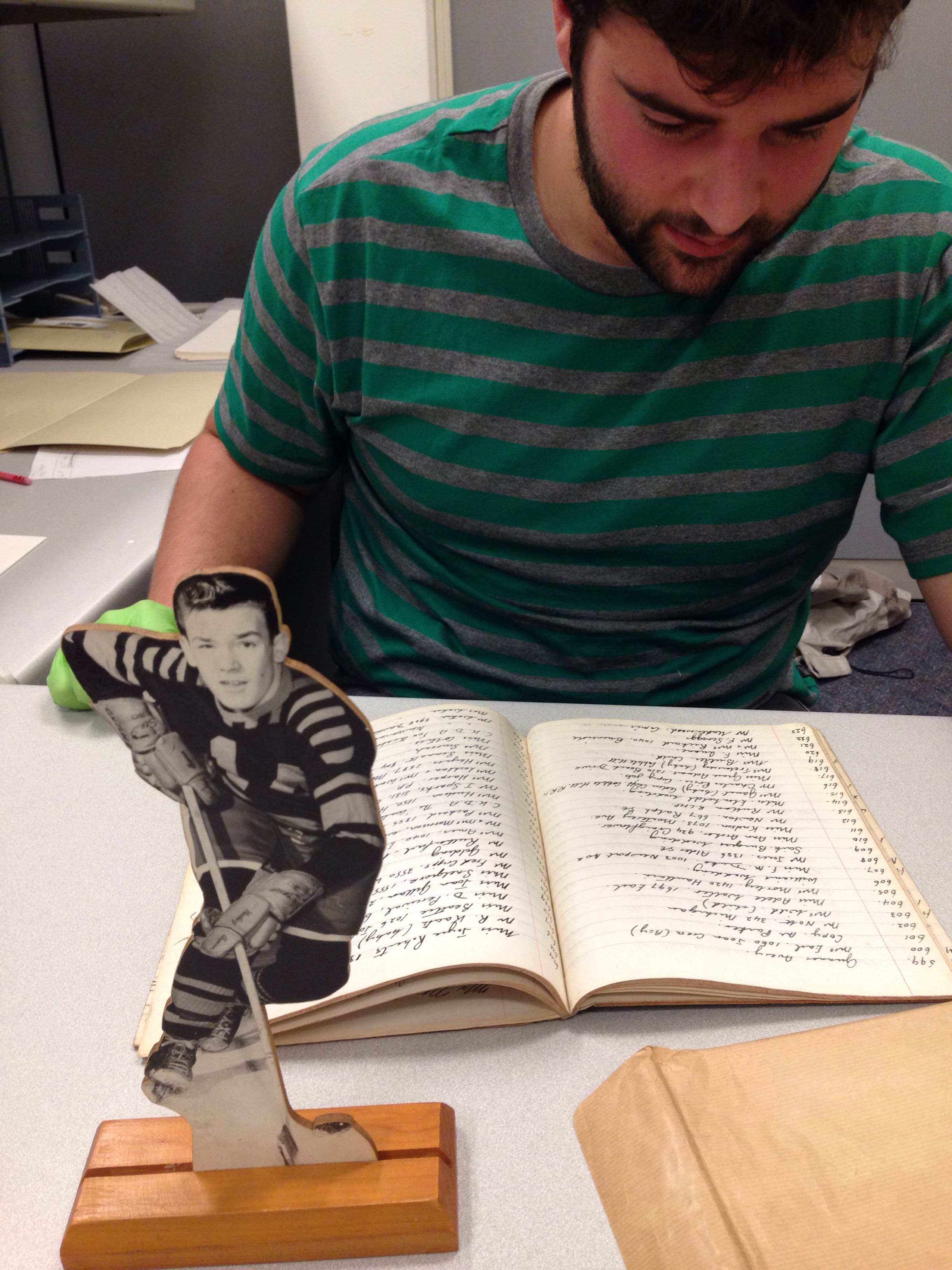

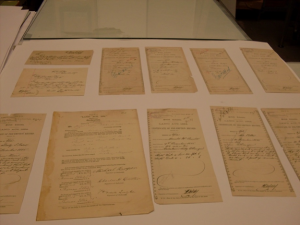

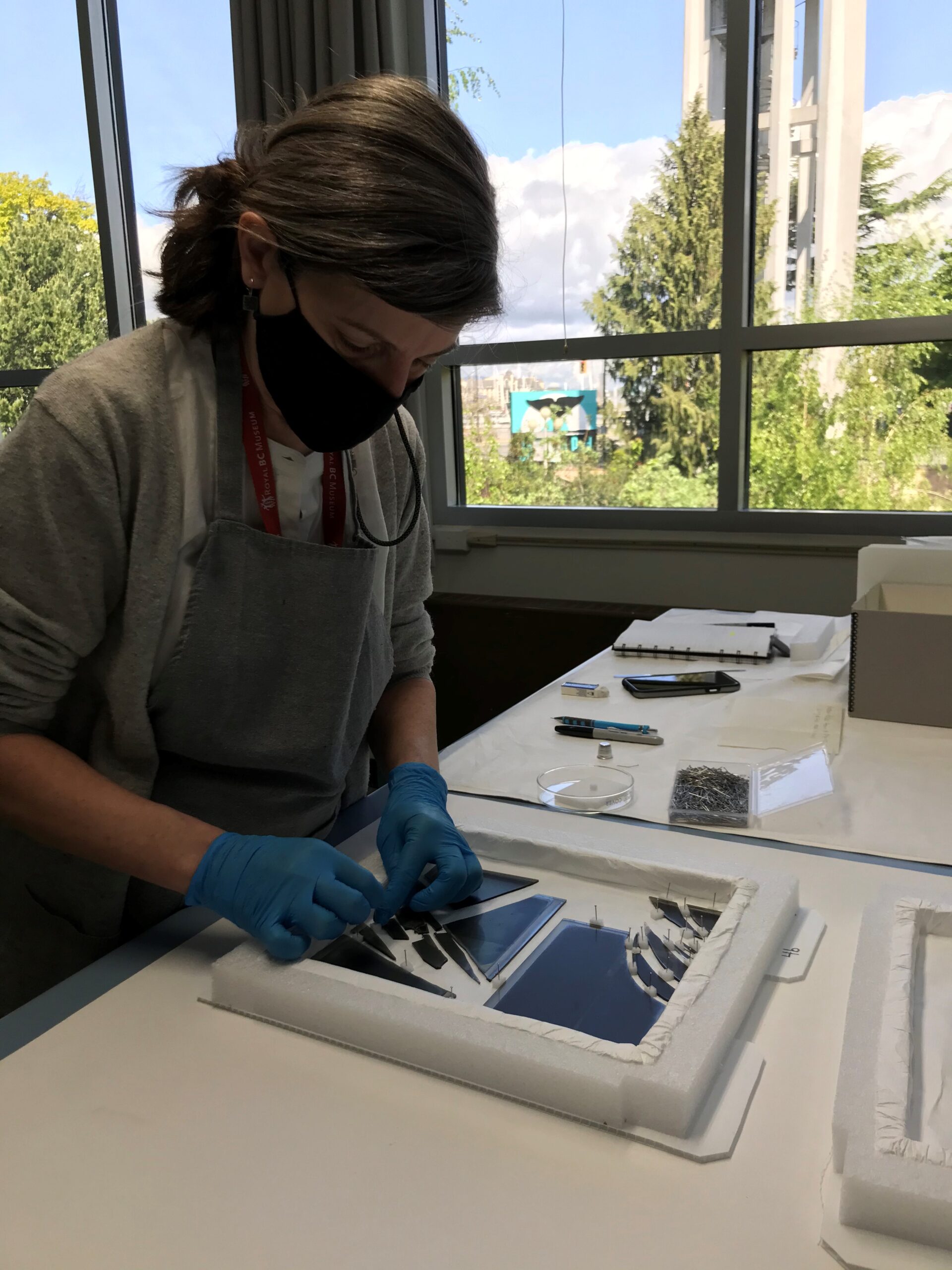

Fig 3. Collection manager Vicky Karas using the transmitted-light table to sort through shards of glass plate negatives to reassemble broken plates preparation for rehousing

The Re-Housing Solution

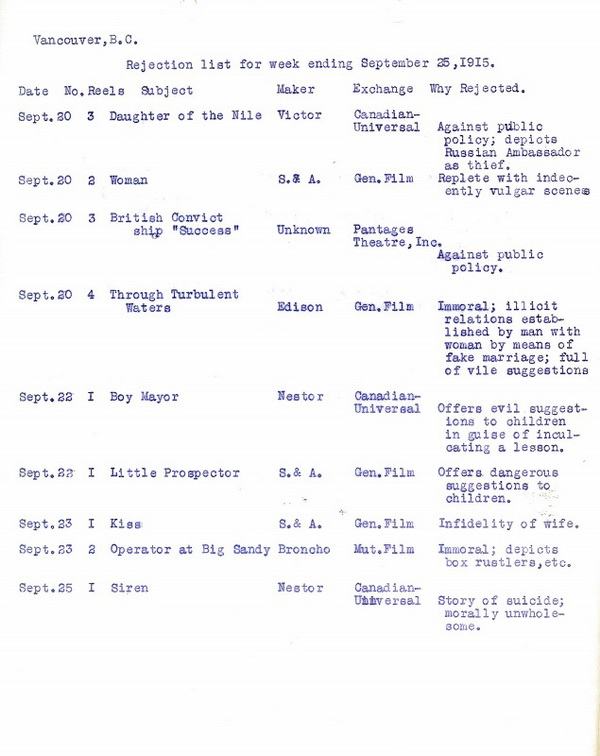

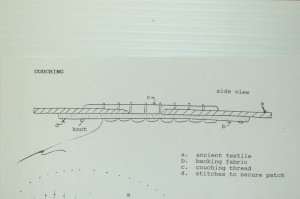

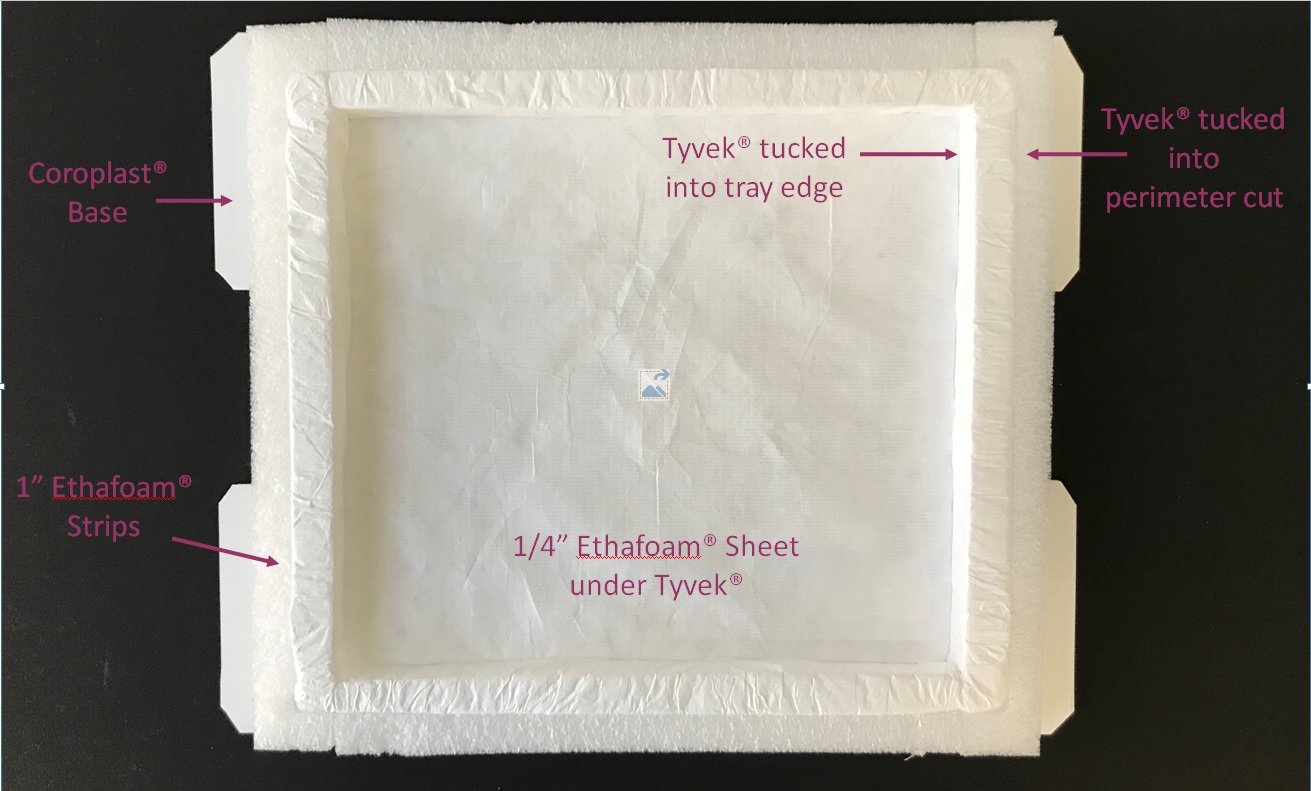

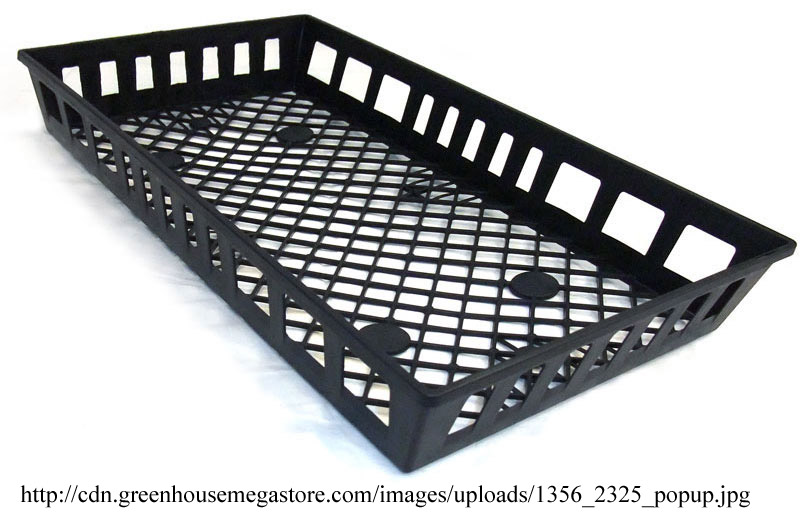

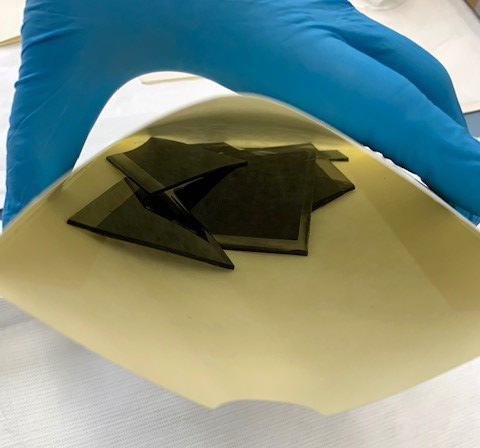

To provide flexible yet sufficient support and protection for broken glass plates for the collection move, these broken plates are being moved into custom-made pincushion trays. The base of this

tray is Coroplast, a corrugated plastic board of archival quality. The edges are one-inch Ethafoam strips with a quarter-inch Ethafoam sheet in the center. The edges and inset surface of these trays are then lined with Tyvek to create a smooth surface for the plates. The Ethafoam is attached to the Coroplast with hot glue and the Tyvek is held in place without the use of any adhesives—it is pressed into the inner edge creases of the tray and under the edge strips, then folded up over the top edges of the tray and tucked into an incision that runs around the sunken portion of the tray.

Figure 4. Construction of pin-cushion tray

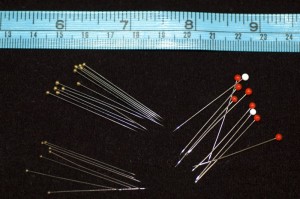

The glass-plate shards are set into the tray, one piece at a time, beginning in one of the tray corners. Each shard is held in place with a small block of Volara foam, which is then pinned in place with a one-inch stainless steel dressmaker’s pin. Once enough pins have been applied to hold this first shard in place, the next shard is added and held in place with more pinned foam blocks until all shards are pinned in place.

These trays are 26 cm x 23.5 cm in the centre, which means they can accommodate the majority of plate holdings. For smaller plates, two can fit in a tray. The external dimensions of the Coroplast base fit within a standard-size record storage box. The hand cut-outs on either side allow for the trays to lifted in and out easily and the one-inch Ethafoam edges provide support for subsequent trays when stacked within the box. Trays are numbered so that their position can be precisely noted and tracked while they remain separate from their original locations and replaced after treatment in the future. (Each tray also has an “a” side and a “b” side, to accommodate instances where there are two plates to a tray.)

The pincushion trays that have been created for this project will provide excellent protection for each shard as they move from one collections storage building to another and await conservation treatment. The downside of this new temporary storage system is that it drastically increases the amount of space these plates are taking up—and in the context of most archival and museum institutions, space comes at a high premium. In this instance however, the museum is moving to a new facility with larger collections stores, so the increase in the footprint of this collection is not a major concern. It is also a temporary storage system.

In the years to come, these plates will be treated and returned to their original storage locations as time permits, and these boxes of trays will not be needed. However, the flexibility of these pincushion trays means that if any new glass plates are acquired broken, there is an existing storage method available and already assembled to provide temporary protection and support while they await treatment.

Acknowledgements

I would like to extend a big thank you to Vicky Karas who has put a great deal of time, care and effort into this re-housing project already . . . and there’s still more to come.

Thank you to Lesley Golding, collections manager for the BC Archives photographic holdings, for her insight during the development of this temporary storage plan and her expertise in regards to location tracking and control.

Free Fly Frog Food post

When I was a kid, I had a range of pets—mostly reptiles and amphibians; no surprise there. To feed my frogs, toads and lizards, I either snuck around the garden with a large aquarium dipnet and trapped flies (which were on our dog’s poop), or I trapped them with a more passive technique.

Today (February 12, 2021) I answered an email about yet another brown anole (Anolis sagrei) that had arrived on some tropical plants, this time at a Canadian Tire outlet in Duncan, BC.

The anole’s new owners are going to set up a terrarium for this little lizard, and why not. They are charming terrarium inhabitants. I gave the owners advice on how to feed and water the lizard, and I decided to detail the trap I made as a kid so they could harvest flies as free food for their new pet.

Here was my trap, made from household items that, when I was a kid, went in the trash (this was pre-recycling).

1) Cut a pop bottle in half and recycle the cap.

2) Cut slots in the top half of the bottle so it fits inside the lower half of the bottle.

3) Cut a hole in the bottom of the bottle (here the hole is in one of the nubbins—corrugations—at the bottom). Flies will find their way in, but when you come to pick up the trap, they likely will not find this hole and will fly upwards.

4) Bait the trap and put the bottom halves together.

5) Tape a parmesan cheese container over the top. Why I use a parmesan cheese container will be explained in a second.

6) Wait.

7) When flies have entered, pick up the entire apparatus and use your thumb to prevent escape out the hole in the corugation.

8) Flies likely will go up and into the parmesan jar when they are disturbed.

9) Remove the tape carefully, and in one smooth motion, lift the parmesan container and screw its cap (this one is red) in place. Bugs will be nicely contained.

10) Now you can simply place the container in your terrarium with the lid open (this is why I used the parmesan container—it has a convenient flap to open, with fly-sized openings). If you are worried about flies escaping before you close the terrarium, then put the parmesan container in the fridge to cool the flies. Then once flies are cool, put the container in the aquarium and let the flies warm up—and watch your pets devour their dipteran dinner.

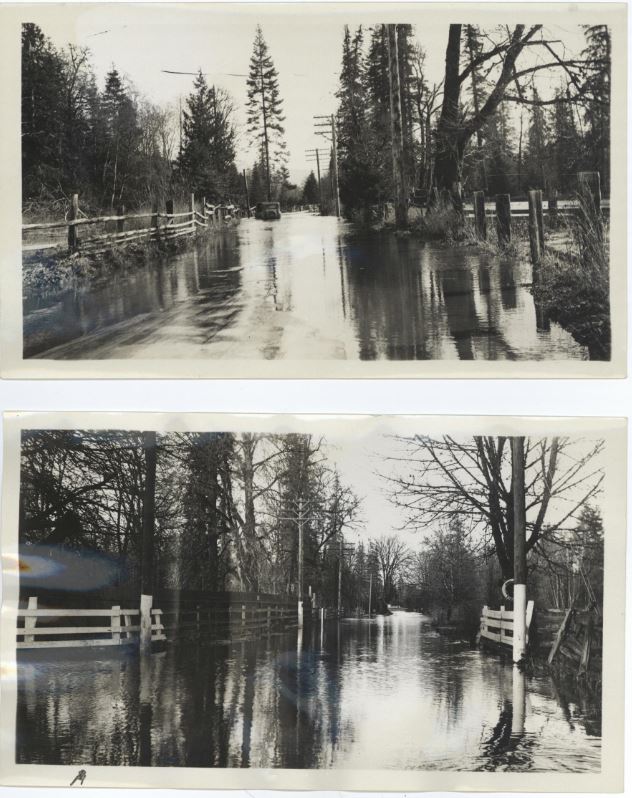

Chilliwacked post

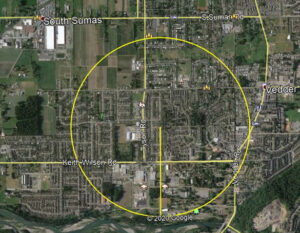

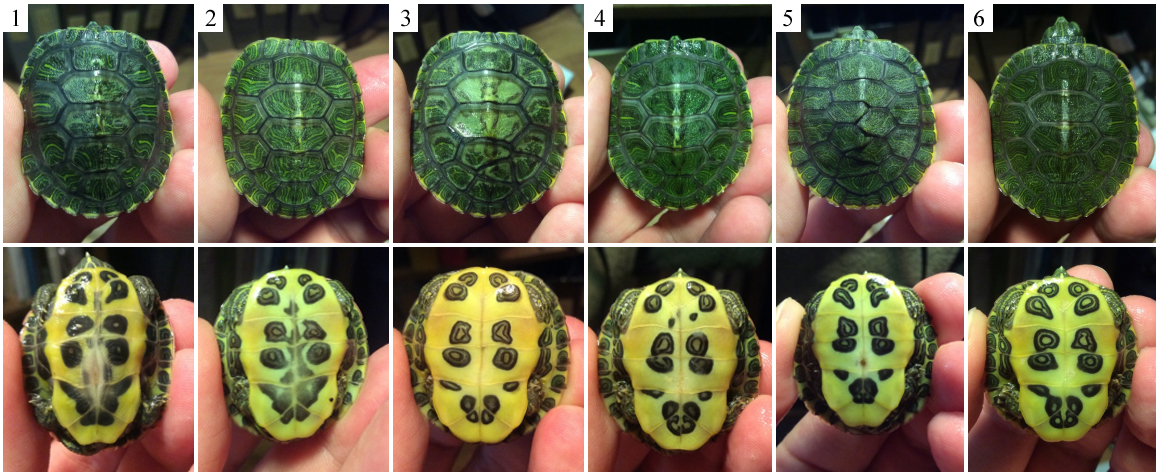

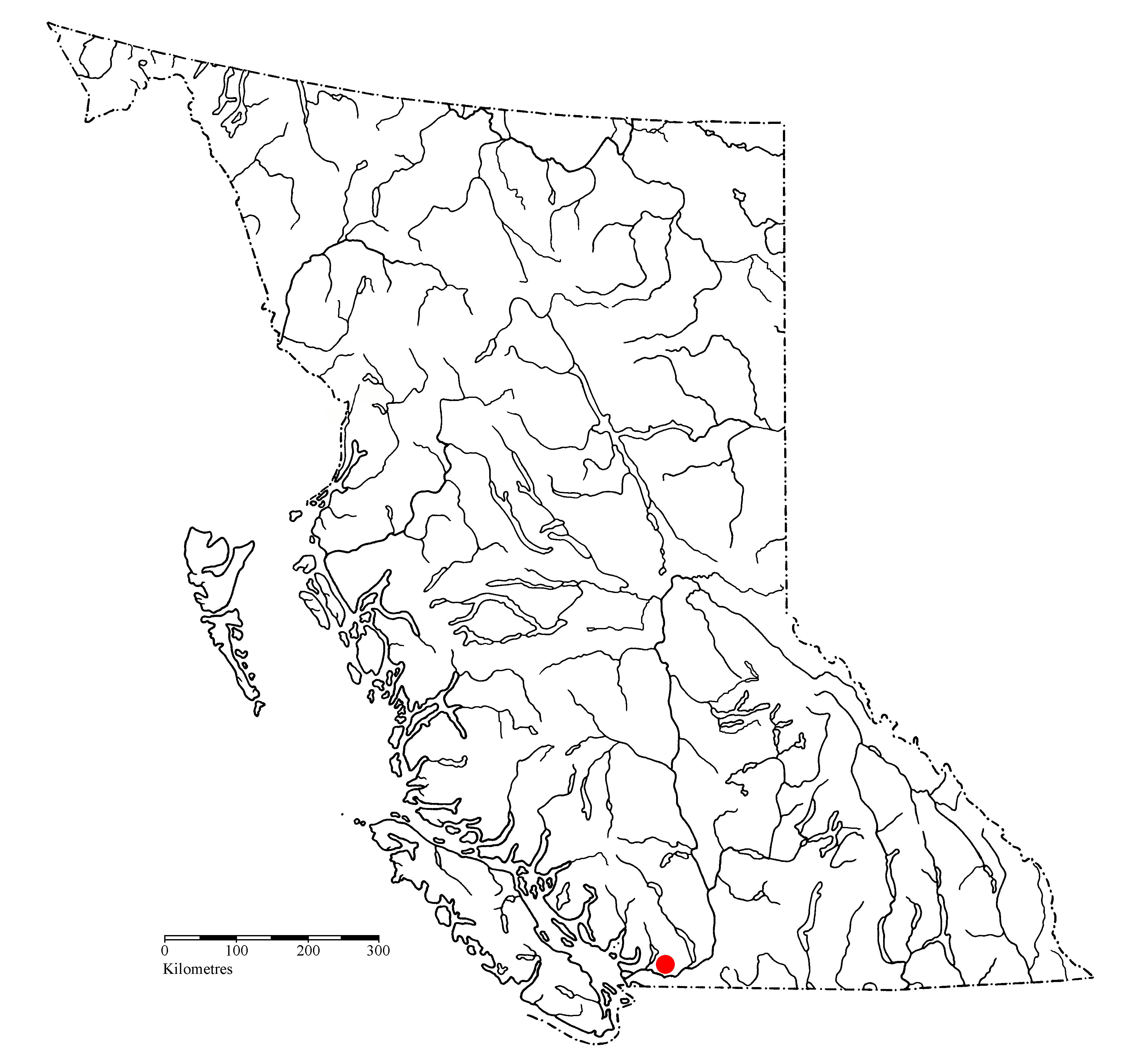

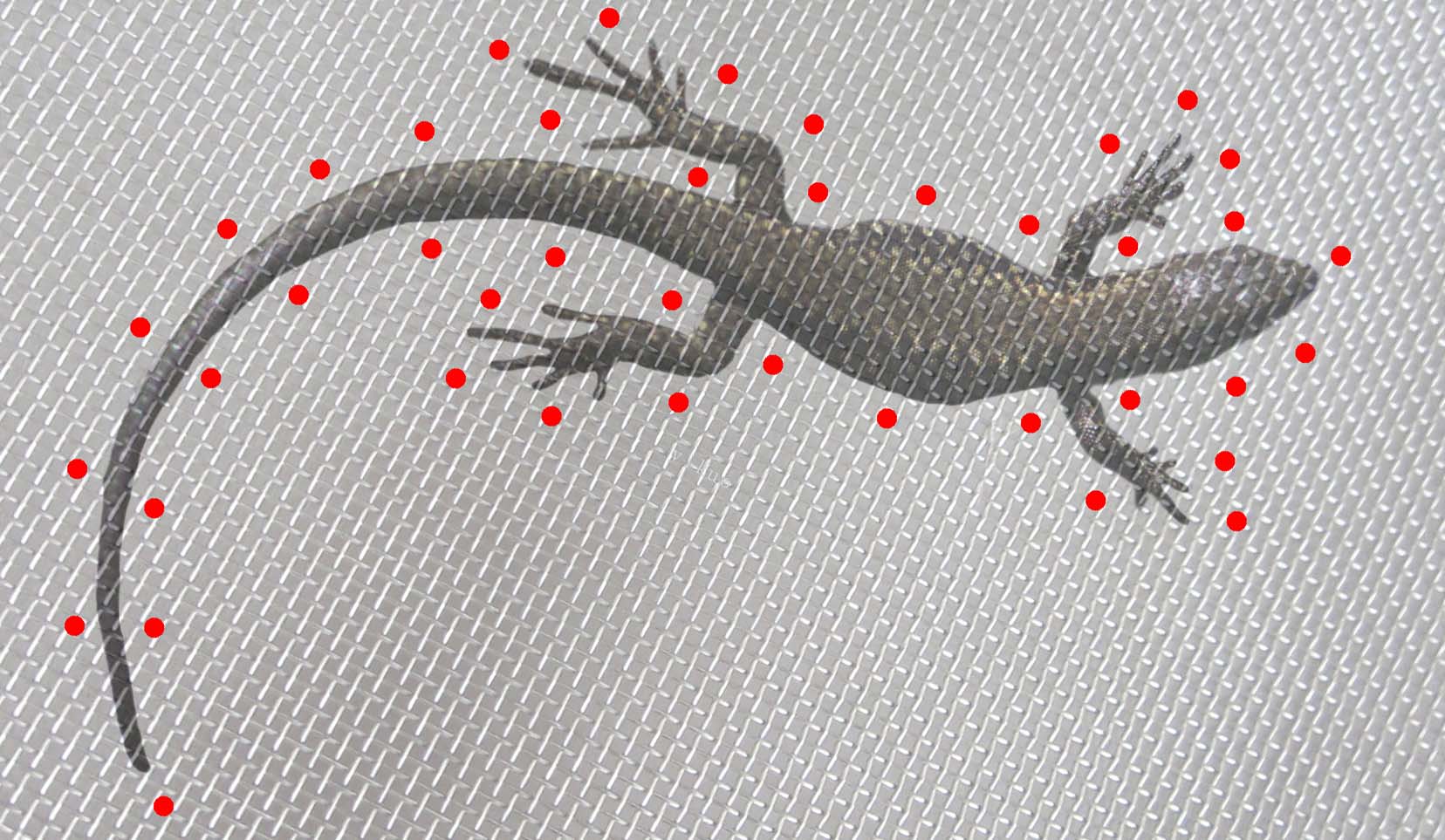

Common wall lizards, Podarcis muralis, were first detected in Chilliwack in late June 2020 by Frances and Georgina Wetmore.

Photo courtesy of Alex Wetmore.

The report came to me in late September to verify the identification, and without a doubt, the photo captured a common wall lizard. After a few quick emails, Christian Lodders pinpointed the epicenter of the colony along Kathleen Drive in Chilliwack. Several gardens in the area now are known to have wall lizards—in other words, they are firmly established. Newly hatched wall lizards were seen this autumn.

How did they get from Vancouver Island (or Denman Island) to Chilliwack? Who knows. Lizards could have been shipped by accident as eggs in a plant pot. One nest creates an instant population of 5–10 lizards, genetic bottleneck notwithstanding. Maybe a gravid female was a stowaway in some camping gear? Mr. Lodders talked to homeowners in the area, and there is no indication anyone intentionally released lizards.

As on Vancouver Island, the end result is the same for Chilliwack—if lizards are not eradicated, they will spread in the area. Under their own power, lizards can disperse one kilometre in 10 years (as outlined in the yellow circle above), and with assistance from humans, their range can expand far more rapidly in the area. With a little help, they could make their way to Washington, and that state would have two wall lizard species: Italian wall lizards (Podarcis siculus) are already established on Orcas Island.

Abstract

Premise of the study: Many arctic-alpine species have vast geographic ranges, but these may encompass substantial gaps whose origins are poorly understood. Here we address the phylogeographic history of Silene acaulis, a perennial cushion plant with a circumpolar distribution except for a large gap in Siberia.

Methods: We assessed genetic variation in a range-wide sample of 103 populations using plastid DNA (pDNA) sequences and AFLPs (amplified fragment length polymorphisms). We constructed a haplotype network and performed Bayesian phylogenetic analyses based on plastid sequences. We visualized AFLP patterns using principal coordinate analysis, identified genetic groups using the program structure, and estimated genetic diversity and rarity indices by geographic region.

Key results: The history of the main pDNA lineages was estimated to span several glaciations. AFLP data revealed a distinct division between Beringia/North America and Europe/East Greenland. These two regions shared only one of 17 pDNA haplotypes. Populations on opposite sides of the Siberian range gap (Ural Mountains and Chukotka) were genetically distinct and appear to have resulted from postglacial leading-edge colonizations. We inferred two refugia in North America (Beringia and the southern Rocky Mountains) and two in Europe (central-southern Europe and northern Europe/East Greenland). Patterns in the East Atlantic region suggested transoceanic long-distance dispersal events.

Conclusions: Silene acaulis has a highly dynamic history characterized by vicariance, regional extinction, and recolonization, with persistence in at least four refugia. Long-distance dispersal explains patterns across the Atlantic Ocean, but we found no evidence of dispersal across the Siberian range gap.

Keywords: AFLP; Caryophyllaceae; Silene acaulis; arctic-alpine; disjunct distribution; phylogeography; psbD-trnT(GGU) spacer; refugia; rpL32-trnL(UAG) spacer; trnL(UAA) intron; trnL(UAA)-trnF(GAA) spacer.

In June of 2018, I was invited to participate in a BioBlitz at the Hakai Institute on Calvert Island. From the initial planning stages, it was clear that this was going to be an exciting and scientifically rich journey. The organizers (Dr. Brian Starzomski, Sara Wickham, and Gillian Sadlier-Brown) invited me to help them to survey the island for “all terrestrial life.” With such a daunting task at hand, I was relieved to discover that a number of other experts, including other entomologists, botanists, lichenologists, ornithologists, and general naturalists, had also been invited.

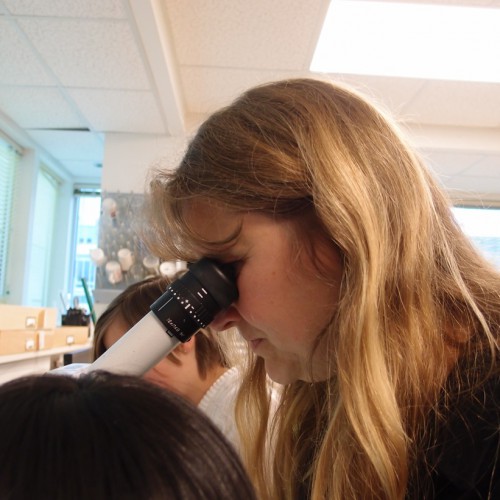

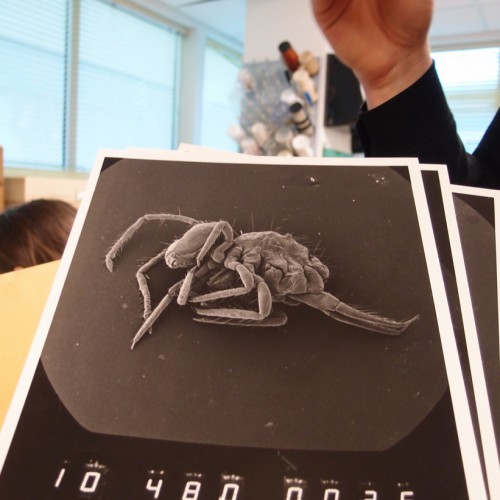

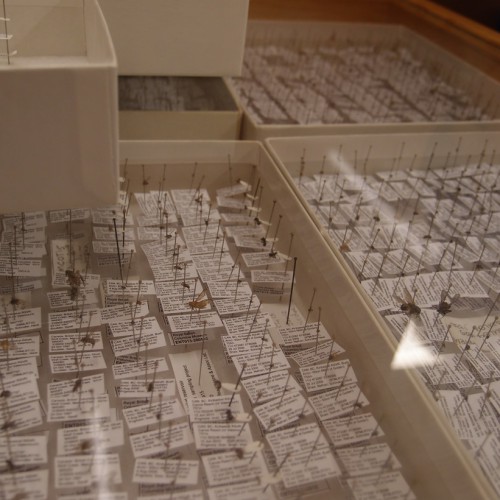

Following a 1.5 hour float plane flight north from Campbell River, we arrived at Calvert Island. Situated about halfway between the northern tip of Vancouver Island and the southern tip of Haida Gwaii, the island truly represents the heart of the Great Bear Rainforest. From the first moments at the facility, we began our task of identifying as many of the species inhabiting the island as possible. The next seven days were spent traversing to the beaches that make up the northwest coast of the island, hiking to inland hilltops, and scouring lagoons at low tide. In all locations, I collected insects, while others collected insects, but also plants, spiders, lichens, and observations of vertebrates. Evenings were spent carefully preparing the specimens gathered each day. A lab full of equipment and enthusiastic staff made it possible to identify specimens, photograph them, and extract tissue. The extracted tissue will be sent to the Centre for Biodiversity Genomics at the University of Guelph for DNA barcoding.

The week was beautiful and tiring, but extremely productive. The insect and spider specimens, over 1300 in total, have made their way to the Entomology Collection at the Royal BC Museum. They are being further identified to species where possible. This single week of field work will produce a valuable snapshot of the insects and spiders inhabiting a special portion of British Columbia’s central coast. They could help us to answer any number of questions about the patterns of biodiversity in our province and the forces that affect those patterns. Stay tuned here for future analyses of these data.

A beautiful coastal habitat, alive with insect diversity. North Beach, Calvert Island. Photo by Joel Gibson.

On March 11, 2011, a magnitude-9 earthquake occurred off the coast of Japan, which triggered a monumental tsunami. The tsunami created massive destruction, taking lives, collapsing buildings, roads, railways and a dam and triggering a series of nuclear accidents. Tsunami debris continues to wash up on the shores of North America and Hawaii, seven years later. The Royal BC Museum has become the repository and permanent home for the biological material collected from this tsunami debris.

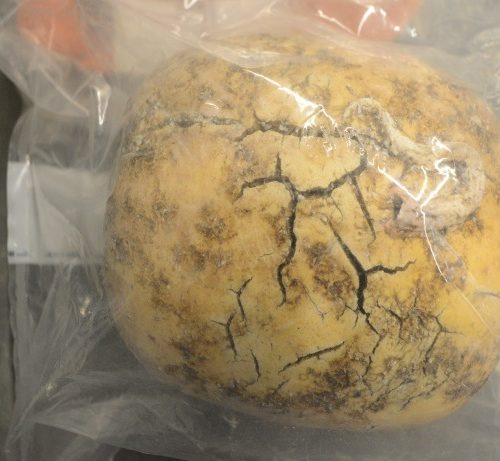

Fifty boxes of organisms collected from tsunami marine debris, both wet and dry, were shipped to the Royal BC Museum. This included some debris that was comprised of man-made objects (substrates), to which marine life was still attached. This sea life was primarily marine invertebrates such as barnacles, bivalves, bryozoans, and hydrozoans. The substrate materials included pieces of fibreglass, masonry, plastics, rubber, Styrofoam and wood, from objects such as docks, boats, buoys, household items and buildings. I agreed to carry out a conservation assessment of the dry material and to advise staff on the best way to store it.

The purpose of storing the Japanese tsunami debris collection at the Royal BC Museum is the long term preservation of the marine life. Research work will be carried out to identify any invasive species that have made their way here from Japan. The stability and the longevity of the substrates will influence the long term preservation of the attached sea life. If the substrates degrade, break apart and disintegrate, the attached colonies and individual specimens will be lost.

I assessed the collection and found that the dry, synthetic, substrate materials were deteriorated and dirty. All were discoloured, bleached, brittle and/or cracked. Some of the substrates were missing sections. There were no plans to remove residual sea salt and sand from the substrates, as this would damage the attached marine life.

I consulted with our senior conservator Kasey Lee, on the best storage conditions for plastics and rubber, as she had just returned from attending a Conservation of Plastics workshop at the Canadian Conservation Institute. The Conservation experts recommended that plastic materials be stored under freezing conditions.

I proposed to Dr. Henry Choong, our curator of Invertebrate Zoology and Heidi Gartner, our Collection Manager of Invertebrate Zoology, that the dry tsunami debris material be stored in a chest freezer, at minus 20◦ C. This would halt the deterioration processes of the plastics, and prevent the loss of marine life. It would also reduce the off-gassing of volatile acids from substrate materials such as wood and rubber. This would preclude the development of Byne’s disease, the chemical and physical breakdown of carbonate-based materials such as shells, due to exposure to acids.

I also suggested that, as a precaution, unbuffered acid-free tissue paper or card be added to the storage containers. This would serve as a humidity buffer because the deterioration processes of some plastics are accelerated in the presence of moisture. As rubber will continue to oxidize in freezing conditions, to slow down its deterioration rate, I also recommended that an oxygen scavenger be added to the sealed storage boxes containing the rubber substrates.

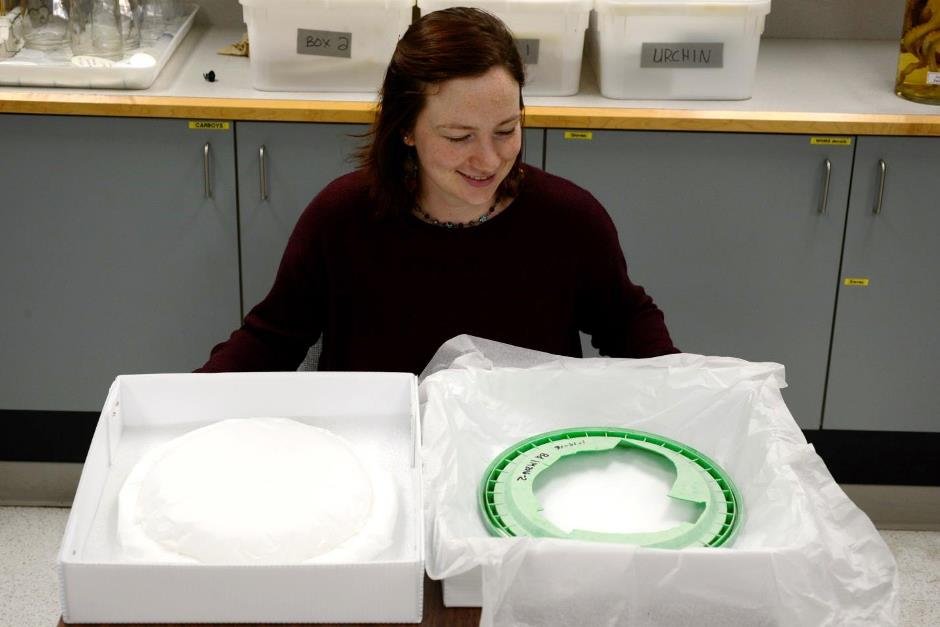

I provided advice to contractor Pascale Archibald on proper storage containers and supplied her with some of the conservation – approved storage materials to house the tsunami debris collection. She wrapped individual objects and cushioned them in unbuffered, acid-free tissue paper in clear polystyrene Durphy boxes. Pascale also made custom storage mounts for the irregular-shaped substrates, using corrugated polyethylene known as Coroplast and polyethylene foam called Ethafoam.

Re-housing of the dry tsunami debris material for long term storage is now completed. The substrates are supported without damaging the attached sea life. An oxygen scavenger will be added to the containers with the rubber substrates and all of the newly-housed dry material will be moved into a chest freezer in the Invertebrate lab.

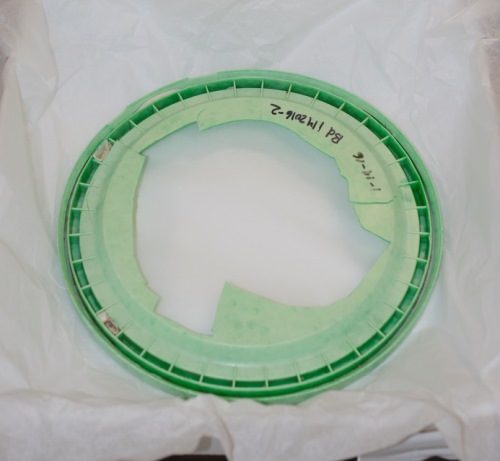

The green plastic lid is now stored on a cushioned mount made of Ethafoam and polyester fiberfill in a custom-built Coroplast box.

Identification of several of the plastics will be carried out with FTIR analysis (Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy) at the Canadian Conservation Institute.

A temporary display of the Japanese tsunami debris collection can be viewed in the Royal BC Museum Pocket gallery in Cliff Carl Hall, until Sunday, October 14, 2018.

In June of 2018, I was invited to Calvert Island by the Hakai Institute to take part in the Hakai Seagrass BioBlitz.

The Hakai seagrass surveys, part of an ongoing long-term research project, focus on unravelling subtidal patterns of microbial ecology, with a focus on several ecologically important marine macroalgae and seagrass (Macrocystis, Nereocystis, and Zostera). Sampling was done offshore with divers, and also in surfgrass habitat on the rocky shore.

The seagrass biomass provides food, habitat, and nursery areas for numerous adult and juvenile vertebrates and invertebrates. A single acre of seagrass may support thousands of fish, and millions of small invertebrates. Because seagrasses support such high biodiversity, and because of their sensitivity to changes in water quality, they have become recognized as important indicator species that reflect the overall health of coastal ecosystems.

During our survey in June, we sampled focal species on various nearshore and intertidal localities around Calvert Island. This work is part of other surveys done at local and regional spatial scales and along the Central Coast in conjunction with the Hakai long-term seagrass and kelp monitoring programs conducted by the Salomon Lab at Simon Fraser University. Our team on the survey comprised experts from the Beaty Museum, Florida Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian, Friday Harbor Labs, and of course, the Royal BC Museum.

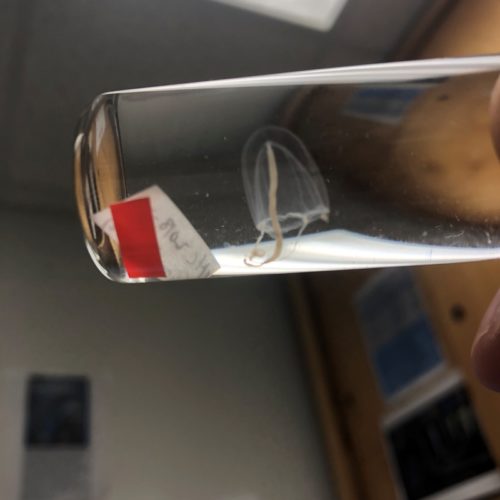

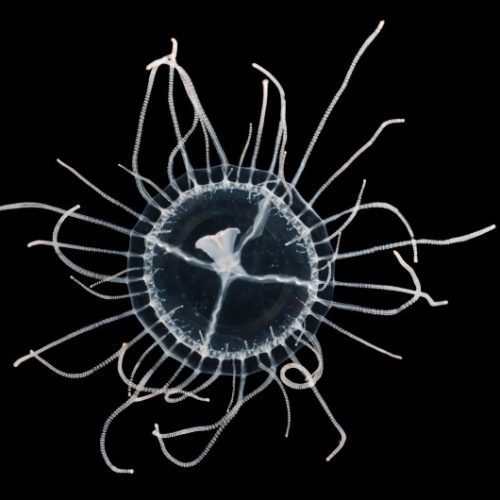

Specimens collected include polychaetes (worms), diatoms, amphipods, hydromedusae (small jellies), and hydroids. I am a hydrozoan specialist, so my task was identifying and studying the hydrozoans (hydroids and hydromedusae) found living on the seagrass.

All specimens were photographed, databased, and sent to be barcoded. The Tula foundation provided the funding for the barcoding through the Barcode of Life Data System-BOLD, University of Guelph. Cnidarian samples (hydroids, etc) will be sent to the Smithsonian for DNA work, as they require different treatment.

The Royal BC Museum’s participation reflects the institution’s important role as a member of the larger biodiversity research community- increased taxonomic resolution of the flora and fauna associated with seagrass helps us understand the structure and dynamics of the seagrass habitats. Another goal of this year’s, and other bioblitzs, is to generate an exhaustive field guide to the algae and invertebrates that can be found in seagrass habitats around Calvert Island.

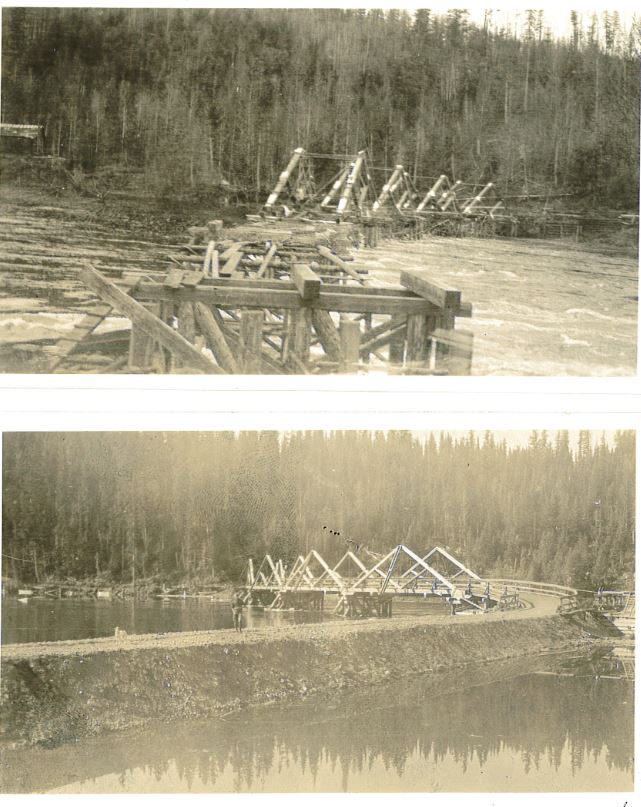

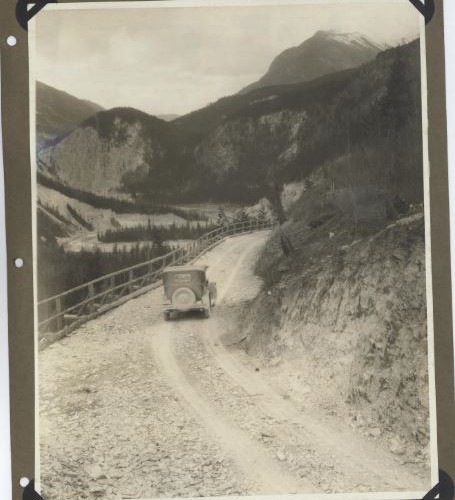

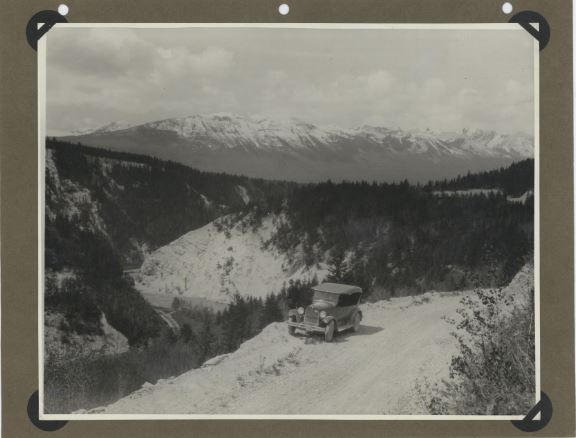

The drive to Golden

Stories of the past inform and shape our understanding of the present. But what happened to the stories less shared, either in public institutions or private sphere? The Royal BC Museum as a public institution is committed to exploring, preserving, and sharing British Columbia (BC)’s diverse heritage. With guidance from the Advisory Committee and in partnership with the South Asian Studies Institute (SASI) at the University of the Fraser Valley (UFV), our work on the Punjabi Canadian Legacy Project (PCLP) Phase 1 in 2015-2017 resulted in the development of new collections, new online educational tools, and community consultations throughout the province. This work was made possible by the generous support from the H.Y. Louie Co. Ltd, as well as the strong institutional support from host institutions around BC.

In the 2015-2017 Phase 1 consultations, communities have expressed the wish to create strong, diverse legacy projects, including K-12 and public education materials, travelling exhibitions to traditional and non-traditional public exhibition spaces, community engagement and development, and other communications. The Advisory Committee are currently helping to shape a fundraising plan for these projects.

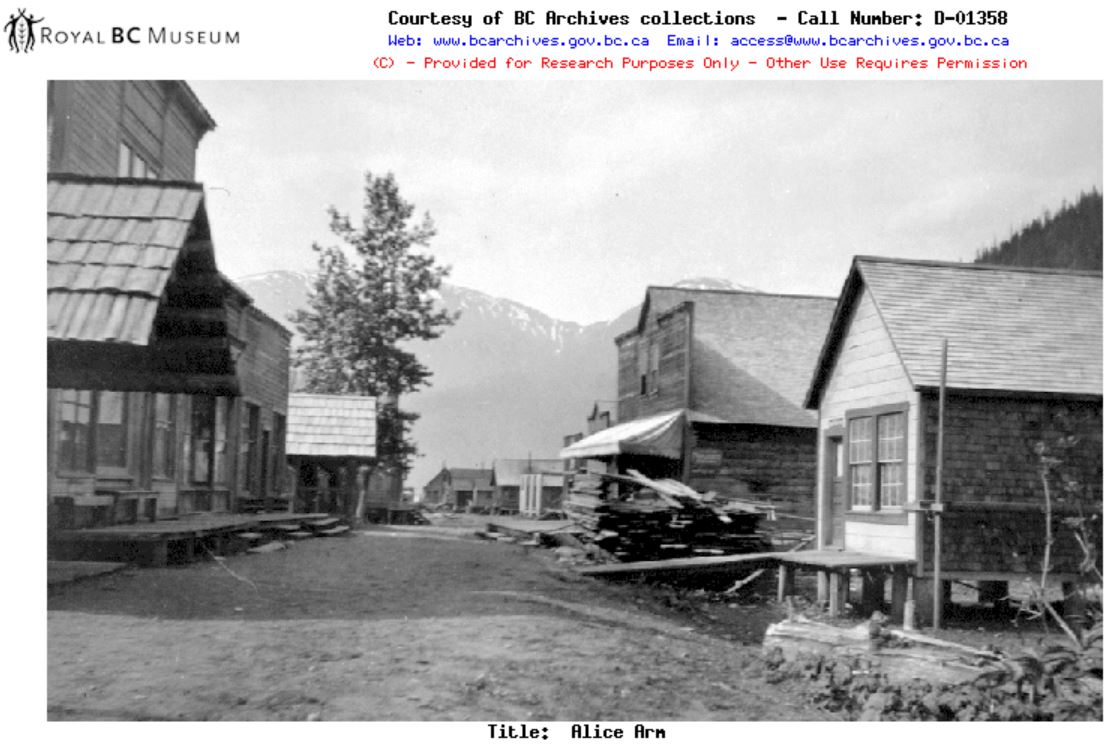

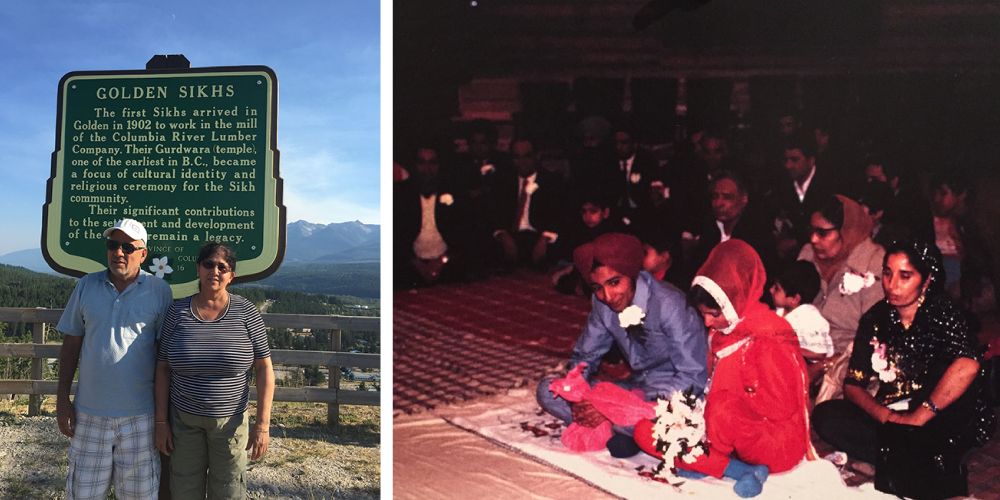

The site in Golden, BC believed to be the location of the first Sikh temple in North America in the early twentieth century.

Following the consultations feedback, currently we are working on the Phase 2 of the PCLP with a modest BC Museums Association Canada 150 fund administered through the UFV, ending in March 2018. In response to community feedback on further outreach, the SASI and the Royal BC Museum collaborate to hold community workshops to continue engagement and collect family history. From summer to winter 2017, we completed workshops in Golden, Prince George, Paldi/Duncan, Kelowna, Vancouver, Surrey, and Abbotsford with support from the host institutions. The project coordinator stayed in each region to collect oral history after the workshops. By March 2018 we estimate to complete 80 interviews. The stories we have collected so far in the project reveal amazing connections of the Punjabi Canadian communities across the province and overseas.

Over the course of this work, our community connections opened the project team’s eyes to community resilience and networks. In July 2017, families with former ties to Golden, BC, a Rocky Mountain town where communities believe to be home to the first gurdwara in North America, held a reunion in Surrey. The event gathered 200 people from around the province who moved away from Golden for work or children’s education. The project team attended this reunion, and met some of the families again in Golden as they scheduled their family annual trips to Golden at the time of our community workshop.

In Golden, we heard about the first Sikh wedding in 1972 from the broom and bride, Swarn and Balbir Patara. At the time there was no Sikh temple in the area. What communities believe to be the first Sikh temple in North America in the early twentieth century left no relics in Golden. They had to ship the utensils, religious items and even a priest from Paldi near Lake Cowichan to perform the wedding ceremony.

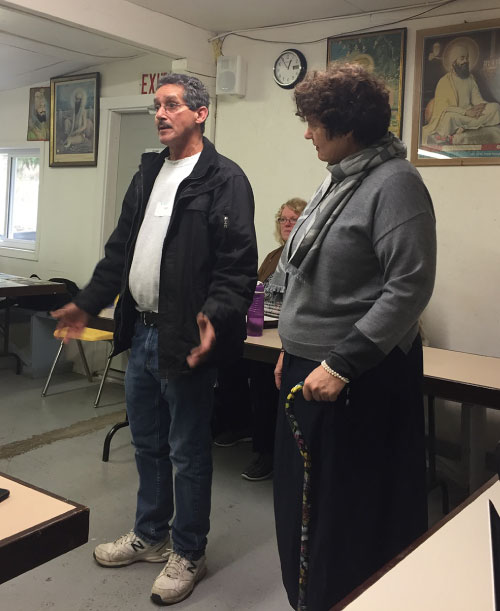

Left: Swarn and Balbir Patara, the first Punjabi couple to get married in Golden with a Sikh wedding in 1972, speaking to us about the local history in front of the plaque in Golden, BC. Right: Swarn and Balbir Patara’s wedding in 1972.

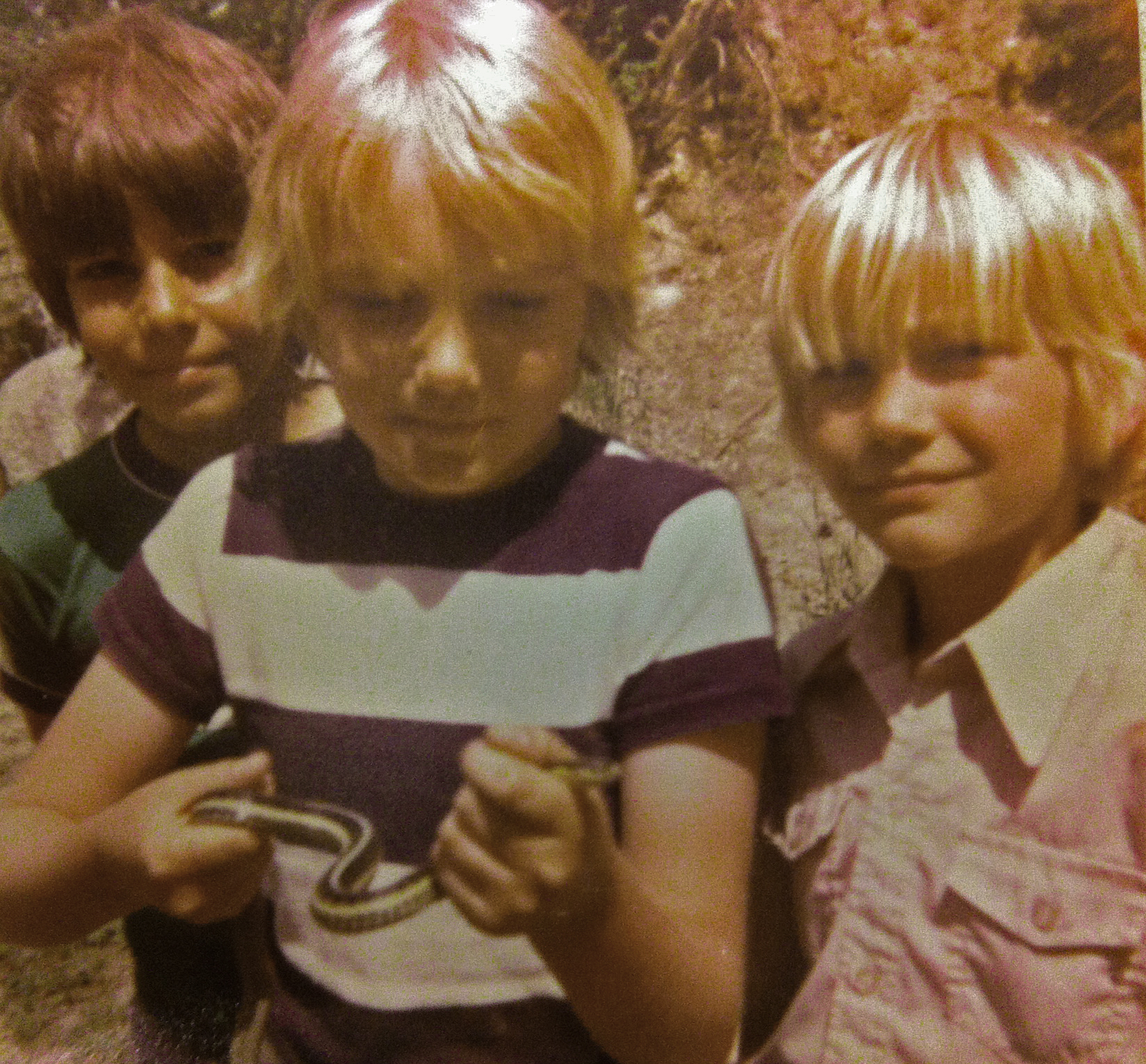

The two local hosts, Davo Mayo, the President of the Paldi Gurdwara and Kathryn Gagnon, Manager/Curator of the Cowichan Valley Museum & Archives, welcomed the attendees at the Community Workshop at the Paldi Sikh Temple in Paldi, BC in October 2017.

In Paldi, we heard again about the traditions in the early days, stories that people shared in other communities as well. At the time, as the community population was small, people travelled to gather at different gurdwaras for holiday celebrations and commemorations together. For example, the Independence Day of India was celebrated at Masachi Lake Gurdwara, and Vaisakhi was celebrated in the Victoria Gurdwara. For these gatherings, all the community members got together in the temple from different cities, and to accommodate them, a lot of mattresses were stored at the temple premises. Many today remember it vividly and would love to keep this tradition alive.

In the amazing journey of working on this project, the connections among many families and communities through generations and places that we have learnt along the way have been heartwarming and great motivations for us to continue this legacy building project.

For more general info on the Punjabi Canadian Legacy Project click here. To see the Phase 2 project updates, click here. A short video on the Paldi workshop can be found here.

Community Workshop at the Golden Sikh Temple in Golden, BC in July, 2017.

Community Workshop at the Ross Street Komagata Maru Museum at the Khalsa Diwan Society of Vancouver in November, 2017.

In July 2017 the Royal BC Museum loaned John Lennon’s 1965 Rolls Royce Phantom V to Rolls Royce Motorcars Ltd for an exhibition at Bonhams of London, UK. I had the distinct pleasure of overseeing the delivery of the Lennon Rolls Royce on that trip.

So how do you drive a three ton car with a custom paint job that is fragile and irreplaceable to Britain? The answer is you don’t. You fly, of course.

The Lennon Rolls Royce is more like a moveable artifact than a car, with most of its value associated with its history and aesthetics rather than its monetary collector value. There’s nothing like it in the world. Accordingly, care and planning for the loan were critical. Even a small ding or mechanical failure means a permanent change to the artifact, one that might require expensive restoration work, or more likely, will stay with the car for the rest of its life. The car is not in perfect condition now, but most of the blemishes are actually associated with the history of the car before it arrived at the Museum. John Lennon used the car extensively in the late ‘60’s and later lent it out to other well-known rockers including the Rolling Stones, the Moody Blues and Bob Dylan. Oh, the stories it could tell.

My epic adventure with the Lennon Rolls Royce began with loading the vehicle into an enclosed trailer for the trip to the mainland, where it would be crated for its overseas flight. It rode the ferry without notice, tucked safely inside its enclosed transport. So the first leg involved a truck trailer and a boat.

Once on the mainland, the Rolls Royce was unloaded from the trailer under its own power, measured and examined, and a crate design was finalized. A carpenter set to work building a reinforced platform that looked like it was built to support an office building. In the end, it is likely that the crate weighed almost as much as the car itself.

When the crate base was ready, I drove the Rolls Royce up a precarious ramp onto the platform. This was no easy feat, as the car is right-hand drive, sports a choke, various vintage knobs and levers, and is not driven regularly, so tends to run a bit rough. There were a few anxious moments when it actually ran out of gas on the ramp, and I feared that the engine-assist breaks would fail to keep me (and the car) from rolling backward into the nearest obstacle. Fortunately the hand brake worked and we were able to tow it up the rest of the way onto the crate base.

The car was then strapped down over and propped up under the axels, just in case the tires deflated in flight, allowing the car to sink and the straps to go slack. The crate was made only slightly larger than the car, with no pads or cushioning as these would abrade the paint as a result of vibration during movement.

The Rolls Royce then flew into Stansted Airport, north of London, UK. The countryside around that part of Britain is amazingly familiar, with the same blackberries in bloom, chestnut trees laden with spikey balls, and, surprisingly to me, fields of Canola (I hail from the prairies). We met the Rolls Royce in the cargo hangar after it cleared customs. I would have loved to see the looks on the faces and hear the banter of those customs agents, but that business took place behind closed doors. The vehicle literally rolled out along a conveyor belt, was lifted off by a humungous fork lift, and deposited into a shower-curtained lorry (when in Rome…). It fit, with at least an inch to spare. See, it’s all about the planning.

Then we were off again through the English countryside, to a tiny little town between fields, churches and tudor-style inns to the outfit that would uncrate the Rolls Royce. When we arrived, the team immediately set to work unbuttoning the crate with the expectation of children on Christmas morning. They knew what was inside and several took a few moments to call their friends and loved ones to brag about their task. Everyone took pictures. I fended off overly-enthusiastic bystanders who wanted to climb in.

Once again there was an adrenaline moment when the improvised ramp split as the Rolls Royce was driven down off the crate base. A piercing crack was heard, followed by the sight of the car dropping a few centimeters. As rubber ages, it becomes stiff and brittle and the tires on the Rolls Royce were definitely on their last… well, legs. A blow out would be disastrous. Just the jarring of the slight fall could have dislodged a brittle joint or loose paint. Fortunately no damage was done and the ramp was reinforced before the front wheels met the same fate.

The next leg of the trip involved driving the vehicle onto a special car-carrying lorry. Fortunately this was a slick job with nothing left to guesswork and ingenuity. The truck actually disgorged its box onto the level pavement where the vehicle could be easily driven inside using fold out metal ramps. Then the driver could take his leave through the overhead side door. These people were professionals with all the best equipment. I left the driving to them.

Once safely loaded into the car-transport lorry, we embarked on another long drive through the English countryside, destined for P & A Wood, official Rolls Royce service company. They had been contracted to put new tires on the Lennon Rolls Royce, and to give it a thorough inspection by trained mechanics, experts that we don’t have on staff at the Royal BC Museum. I marvelled at how the lorry navigated the tight traffic circles, passing through one quaint town after another. My driver was kind enough to explain to me the processes for thatching roofs and creating the decorative pargetting on the plaster cottages we passed. The sheep and cows raised inquisitive heads and the ubiquitous pigeons dared us to hit them as they scavenged at the roadside.

After an hour or so, we finally reached our destination, a very impressively appointed set of newer buildings sporting Rolls Royce/Bentley showrooms, parts stores, and two service shops. We unloaded the Rolls Royce on the street, almost causing a couple of accidents as passing motorists craned to have a look, and drove into a spotless building that looked more like a showroom than a service department. The Lennon Rolls Royce was deposited amongst its kind, with Fred Astaire’s 1927 Rolls Royce Phantom I just ahead of us. I felt a sense of awe, but surprising to me, so did the various workers inside, who were thrilled to see the famous John Lennon Phantom V up close. The digital shutters began snapping again all around me. It was and will always be a privilege to be in the company of such a world famous piece of history.

I left England shortly after depositing the Lennon Rolls Royce with P & A Wood, headed home to my office job at the Royal BC Museum. The Curator, Lorne Hammond, would take my place in London a few days later, assisting with the installation and media events at Bonhams. The rest will be Rolls Royce history. It appears that they have finally forgiven John Lennon for daring to mess with their refined brand image. Time has a way of sorting out those things. But the excitement around the Lennon Rolls Royce appears to be timeless.

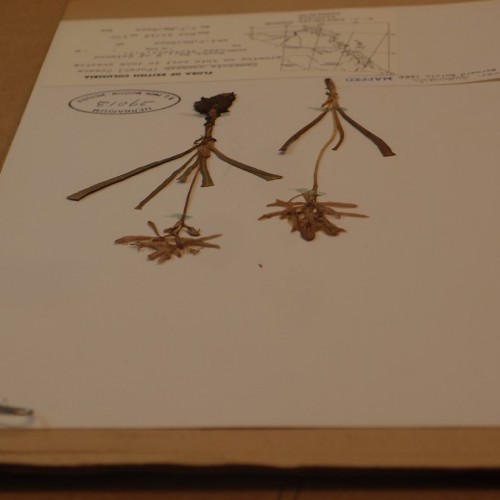

B.C. is home to more than 3,000 flowering plant species; the richest flora in Canada. This botanical exuberance is our legacy of a complex geological history coupled with a varied landscape and climate. The result is the occurrence of many rare species in our province.

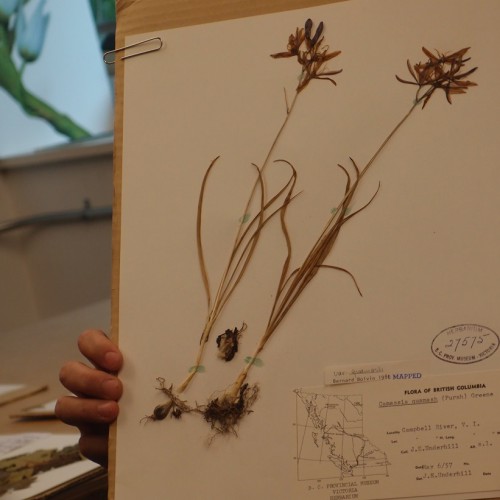

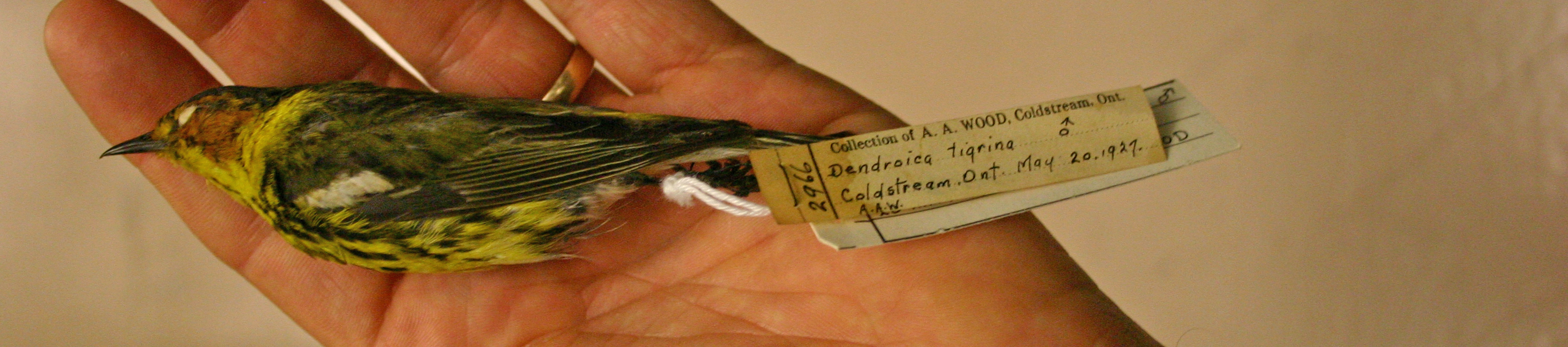

At the Royal British Columbia Museum Herbarium, we keep dried and pressed examples of the province’s plants including at least one specimen of each of the rare species. These identified and labelled specimens are accompanied by information about place and date of collection, collector, and often details of the local environment. The specimens serve as proof, or vouchers of the species in B.C. and as a reference for comparison of newly collected material.

Rare plants can be classified into four groups:

1. Those that occur at a single or few localities, each population with few individuals.

2. Those that occur at several localities and are locally common.

3. Those that occur in many areas, but in low numbers.

4. Those that occur in a restricted area but are abundant

Rare plants, in many cases, are endangered plants because compared to widespread species even minor disturbance can cause them to disappear or be seriously affected. However, some rare species on distant difficult-to-reach mountains may not be endangered, whereas large populations in areas under intense influence from human activity can be seriously endangered. Climate change is one disruptive phenomenon that will reach all plants.

My work focuses on the environmental history of the province and how that history might explain the distribution of rare species. Furthermore, lessons learned from ancient history provide insights into the potential fate of our flora, including rare species, in the event of major climatic warming associated with the “Greenhouse Effect”.

With the potential for warming of about 2-4 degrees Celsius, in the mean annual temperature, we can expect major changes in vegetation and consequently major impact on rare species. In this context all rare species on whatever scale whether local (such as Galiano Island), regional or provincial must be considered potentially endangered. The reason for this concern, is that we do not know how plant species will respond to climate change. We do know that change will effect plants somehow. Rare species are most sensitive because even the smallest impact may destroy a population; and because a species is rare, once it disappears, there will be no reservoir in British Columbia from which it can recover. The greatest concern is for plants that are not only rare and impacted by climatic warming but also under stress from direct human activities such as logging, agriculture or urban development; For all rare plant species we must consider reducing these added stresses to help them survive the broader assault of Global warming.

As climate change proceeds we may expect some rare or endangered species to benefit and expand. These would include species of dry open habitants such as the garry oak (Quercus garryana) woodland and meadows of south east Vancouver Island and adjacent Gulf Islands. This region contain a very high concentration of rare plants such as the endemic Macoun’s meadow-foam (Limnanthes macounii), bristly manzanita (Arctostaphylos columbiana), golden Indian Paintbrush, (Castilleja levisecta) a balsamroot (Balsamorhiza deltoidea) and many others. The rare and endangered species of the arid lands of the southern Okanagan – Thompson and Kootenay may benefit; provided we conserve sufficient habitat for them and provide corridors for their migration. These species thrive under hot dry setting and could spread northward and up-slope as forests and woodland succumb to drought. Good examples include the Mariposa lilies (Calochortus spp).

The losers will be plant species of moist and cool or cold settings; inhabitants of the alpine zone and wetlands. Eventually, forests will spread up-slope, eliminating open alpine habitats and species especially on southern low elevation alpine areas. In some places weedy species such as knapweed, may expand into pristine subalpine and alpine zones as live stock carry seeds through expanding grasslands.

Wetlands in all parts of the province, especially dry regions such as the Gulf Islands and adjacent Vancouver Island and the southern interior, will be at greatest risk. Studies of bog and lake cores from these areas clearly reveal that water levels, water chemistry, and as a result, plant communities change markedly as climate alters. For example, in our area many smaller lakes and ponds were neutral to alkaline, precipitating the limey sediment called marl. Some medium-sized lakes were completely dry in Interior B.C. where the mean annual temperature was about 2 C warmer. Once suitable conditions for a wetland plant disappear, the plant disappears. Unlike terrestrial plants, wetland plants cannot disperse up-slope or up-valley along a corridor or gradient of suitable habitat. Somehow they must jump to the next suitable wetland before the one in which they live dries up. Combine natural change of wetlands with increased demand for water by livestock, moist sites for agriculture, drinking water, irrigation and invasion by introduced species such as Purple loosestrife and you have a prescription for very difficult times for endangered wetland plant species.

Each local area should know what rare and endangered species occur there and where they grow. Learn how to recognize your rare plant residents. Consider adopting the plants and their locality and monitor the population for increases or decreases. Develop local policies and strategies to minimize the impact on these special plants and places. Take responsibility for conserving the natural legacy of thousands of years of history; some of those rare species may become crucial elements of the new vegetation that is to come.

*Article modified from original printed in the Active Page Galiano Monthly Magazine, January 1991.

Protected: In a Manner of Speaking download

As many of you will have noticed, there is a new archives collection search database. It uses a system called AtoM (Access to Memory) which is also used by City of Vancouver Archives, UBC Rare Books and Special Collections, SFU Archives, the World Bank and others. It is quite different from the old “blue and white site” with which we have become familiar, and with which – with all its faults – we have become comfortable. However, the old search site, dating back to the early years of the internet, will soon be gone, having survived longer than most websites.

Detailed instructions for the new system are available as well as a brief search guide, but for those who have used the old site, the following search tips may be useful.

>Use * (instead of ?) as a wild card (e.g. judg* to retrieve judge, judgement, judgment, judging, etc.), and ? (instead of #) for single character substitution (e.g. ver?g?n will find Veregin, Verigan, Verigen as well as the more common spelling of Verigin).

>Use AND (all caps) to combine terms (e.g. alma AND russell) and quotation marks to specify an exact match (e.g. “alma russell”) Otherwise the search will be treated as an OR, i.e. match any terms, search. For example, alma russell will retrieve descriptions with Alma Russell as a phrase and with both Alma and Russell somewhere in the description (not adjacent), but also records with only Alma and with only Russell.

>With the exception of the Identifier field in Advanced Search, search terms can be in upper or lowercase. When using Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT) – which must be in uppercase – enter the entire search statement in uppercase if you wish to avoid having to shift from lower to upper case, e.g. ALMA AND RUSSELL AND WAR.

>Enclose any term or number with a hyphen or other special character in quotation marks, e.g. “MS-0055”, “I-00204”, “e/c/w96a”. Otherwise the hyphen, slash, etc. will be ignored. For example, if MS-0055 is searched without quotation marks (other than in the Identifier field), the results will include records descriptions with only ms (or MS) and only 0055 present as well as those with both.

>The Identifier field option in Advanced search is unique in that it is not only case sensitive but it does not require quotation marks to search a number with hyphens designated as an identifier (e.g. call number, accession number, item number). A string of such numbers can be entered with spaces in between to search on any of the terms entered, e.g. MS-0054 MS-0055 G-02580 G-02581 G-02582. Note that not all numbers are considered identifiers, e.g. HP photo numbers are only searchable in a basic or Any Field search.

>Use the General material designation filter in Advanced search to limit results to one type of record, e.g. textual, sound, etc. By default the system searches all types (except library material and vital event records which are in separate databases).

Limit search results to series level descriptions to view textual records at the same level as the blue and white site. If you know the MS or GR numbers, use the Identifier search option in Advanced Search which will also yield only the series level description. Similarly, a PR number will produce only the fonds level description.

>When viewing an individual series level record description use the Quick Search feature in the left-hand column to search for specific lower-level record descriptions. If the series level description has an attached finding aid (in the Notes area), click on the link to open the PDF and use CTRL-F to search for specific files or items.

Next: Basic search vs Advanced search

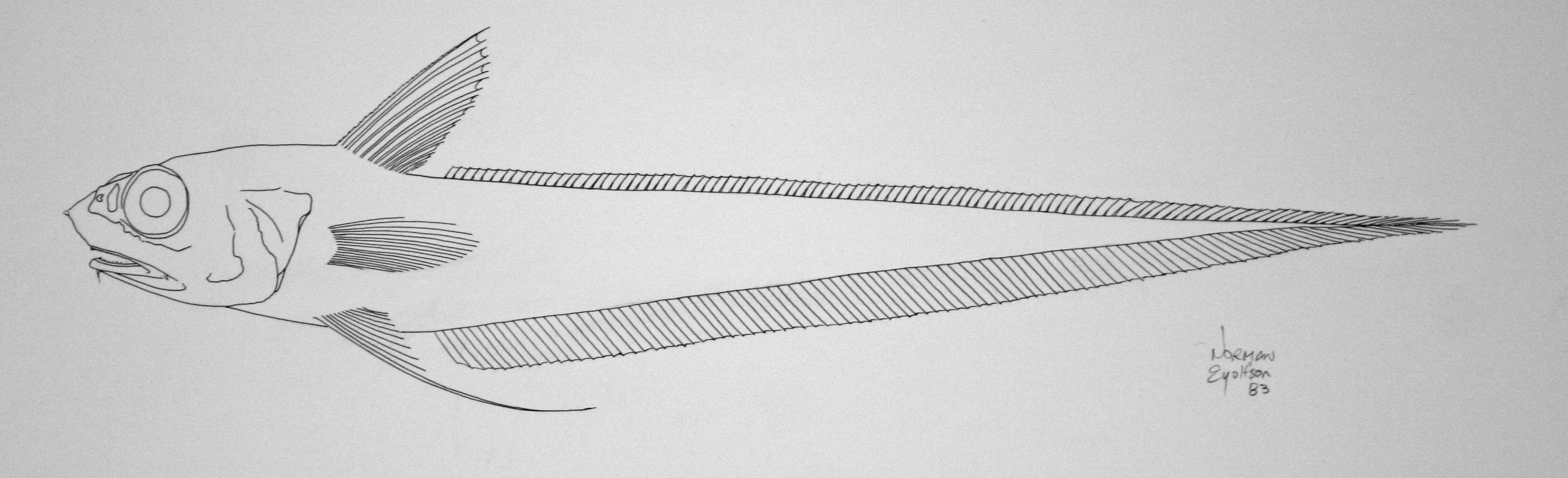

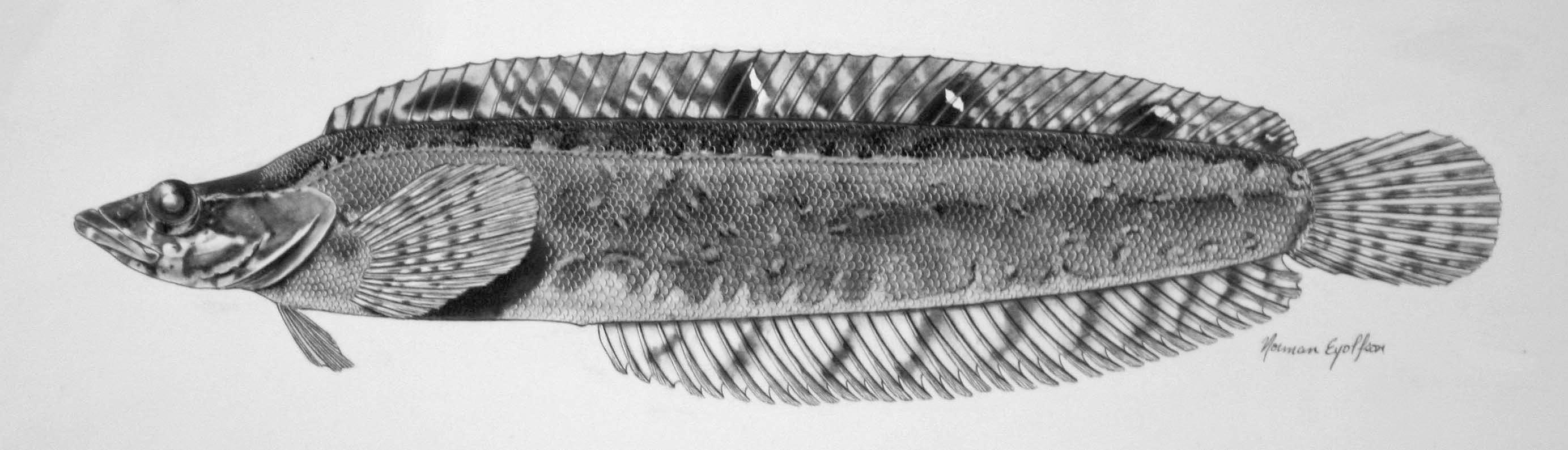

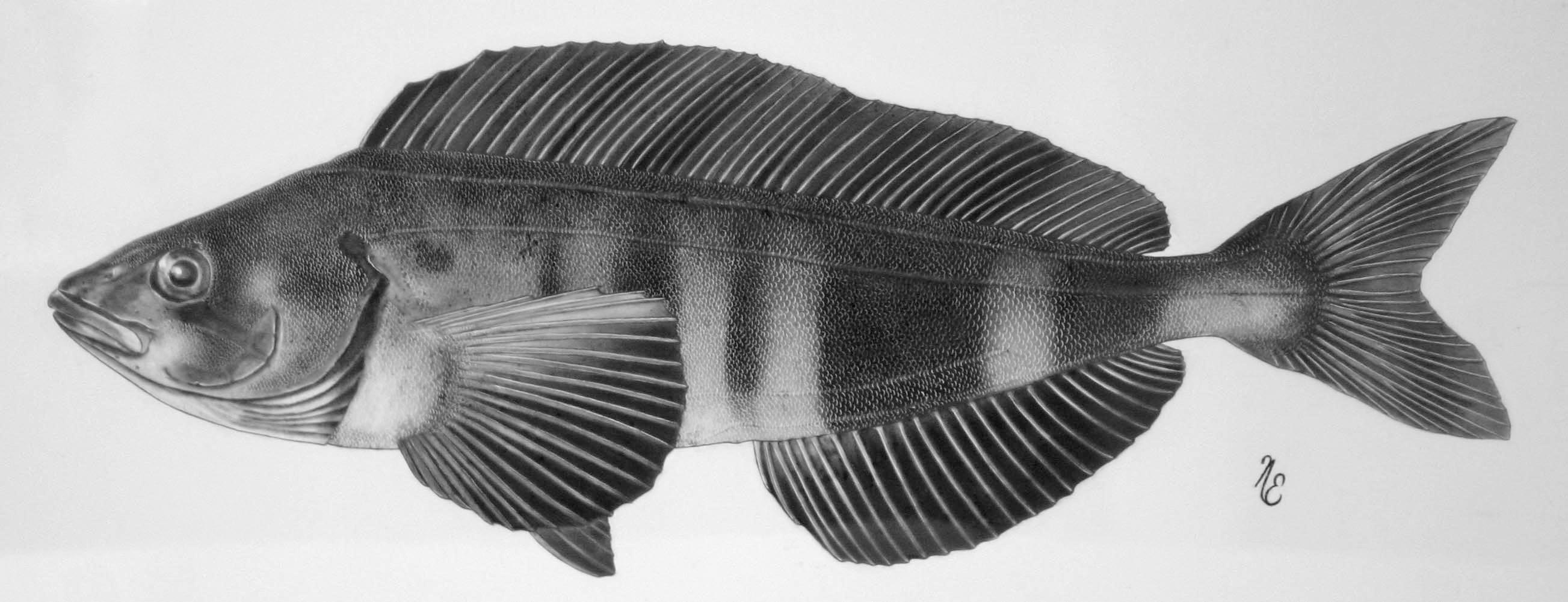

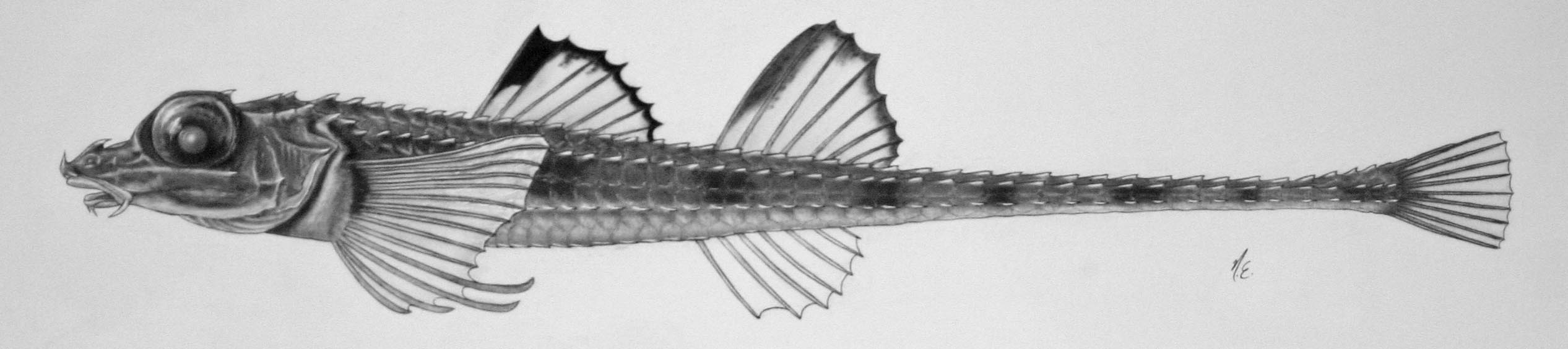

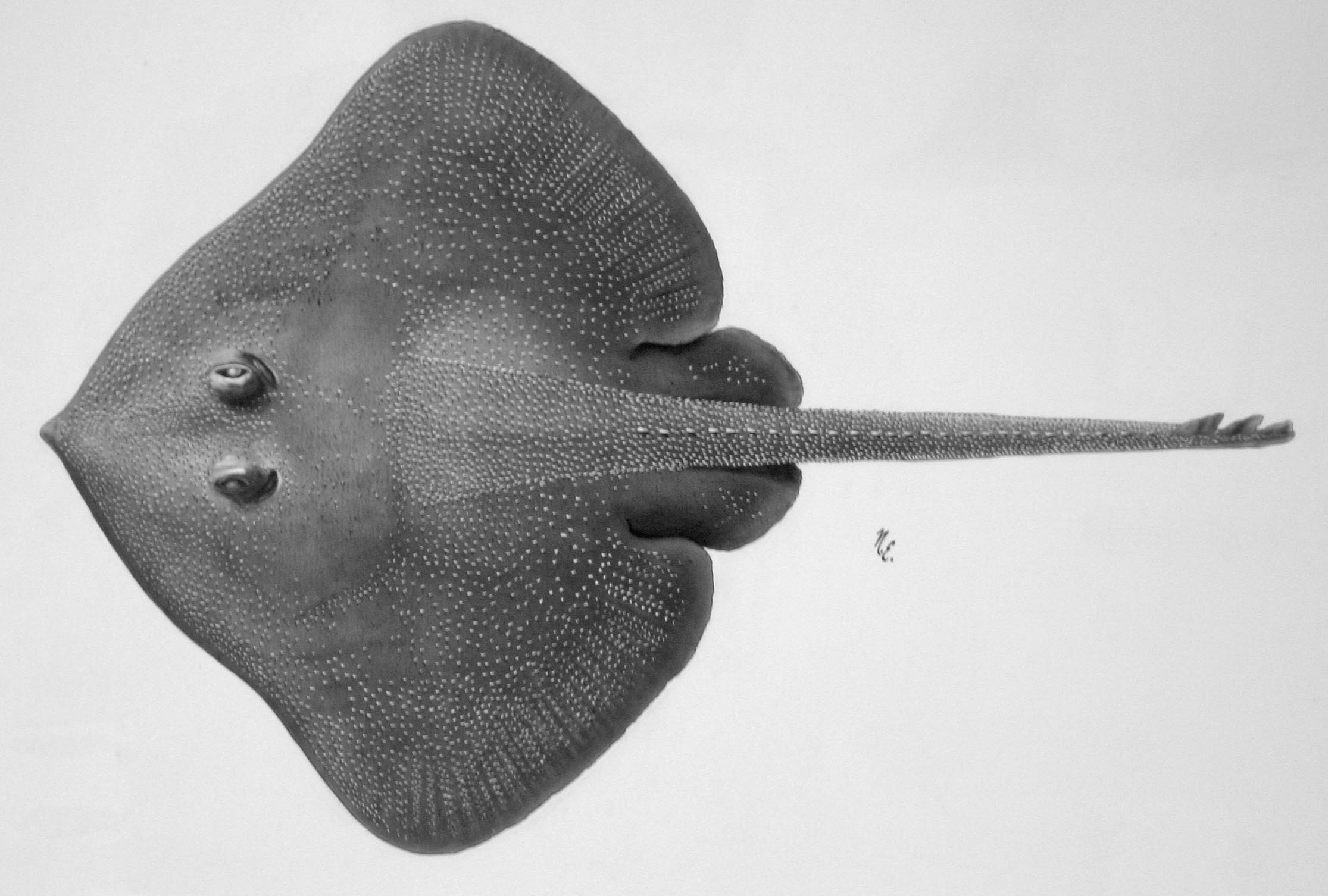

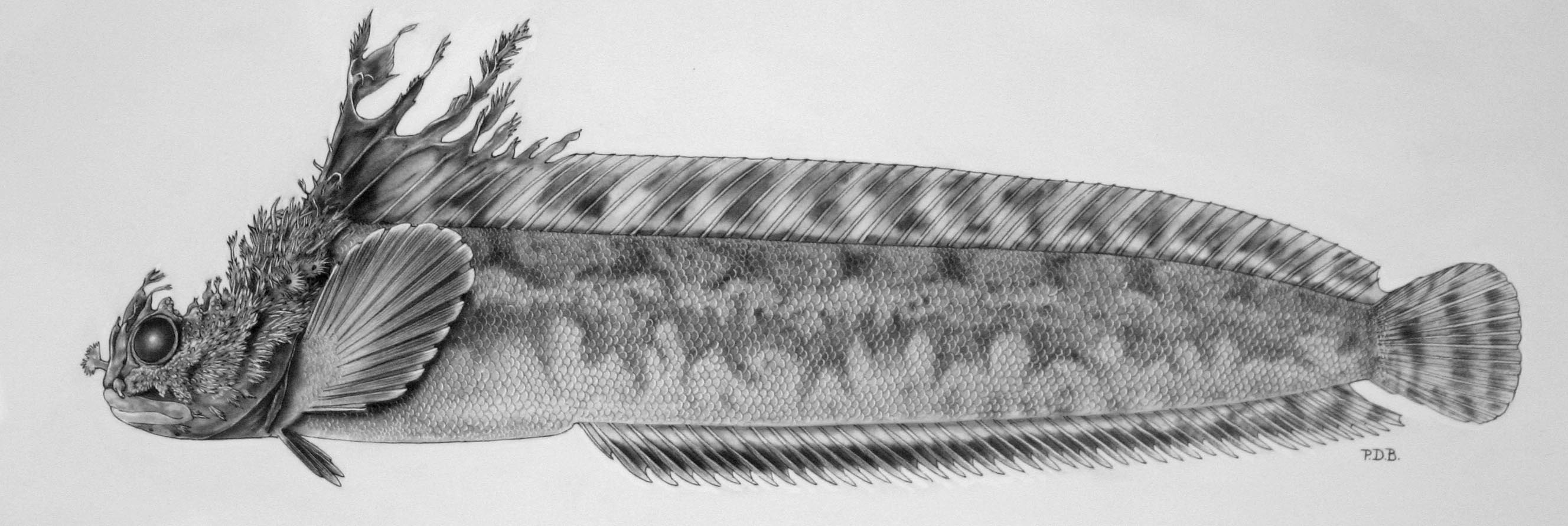

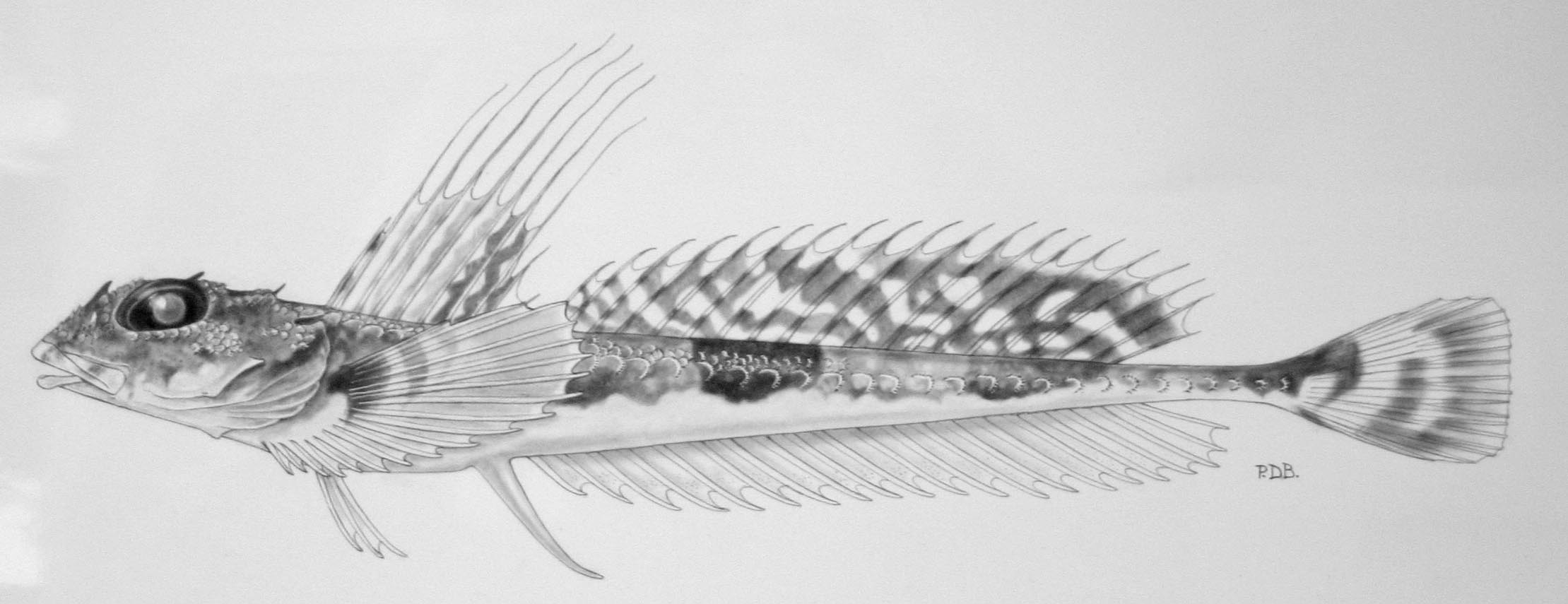

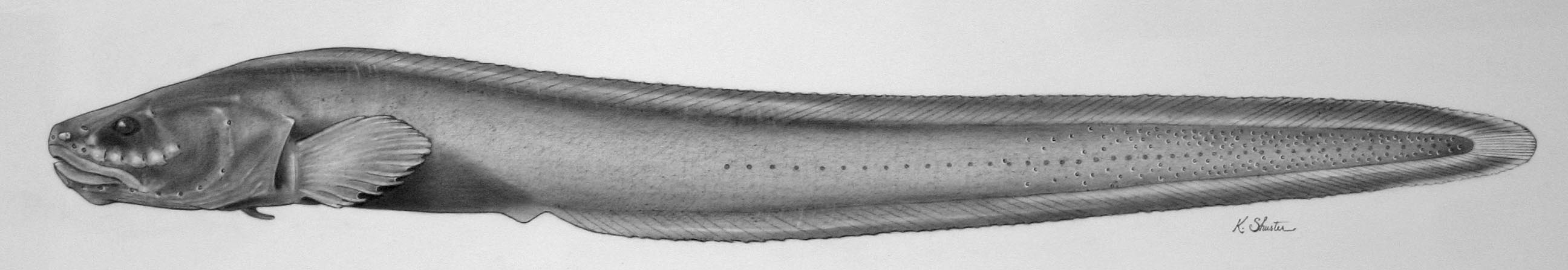

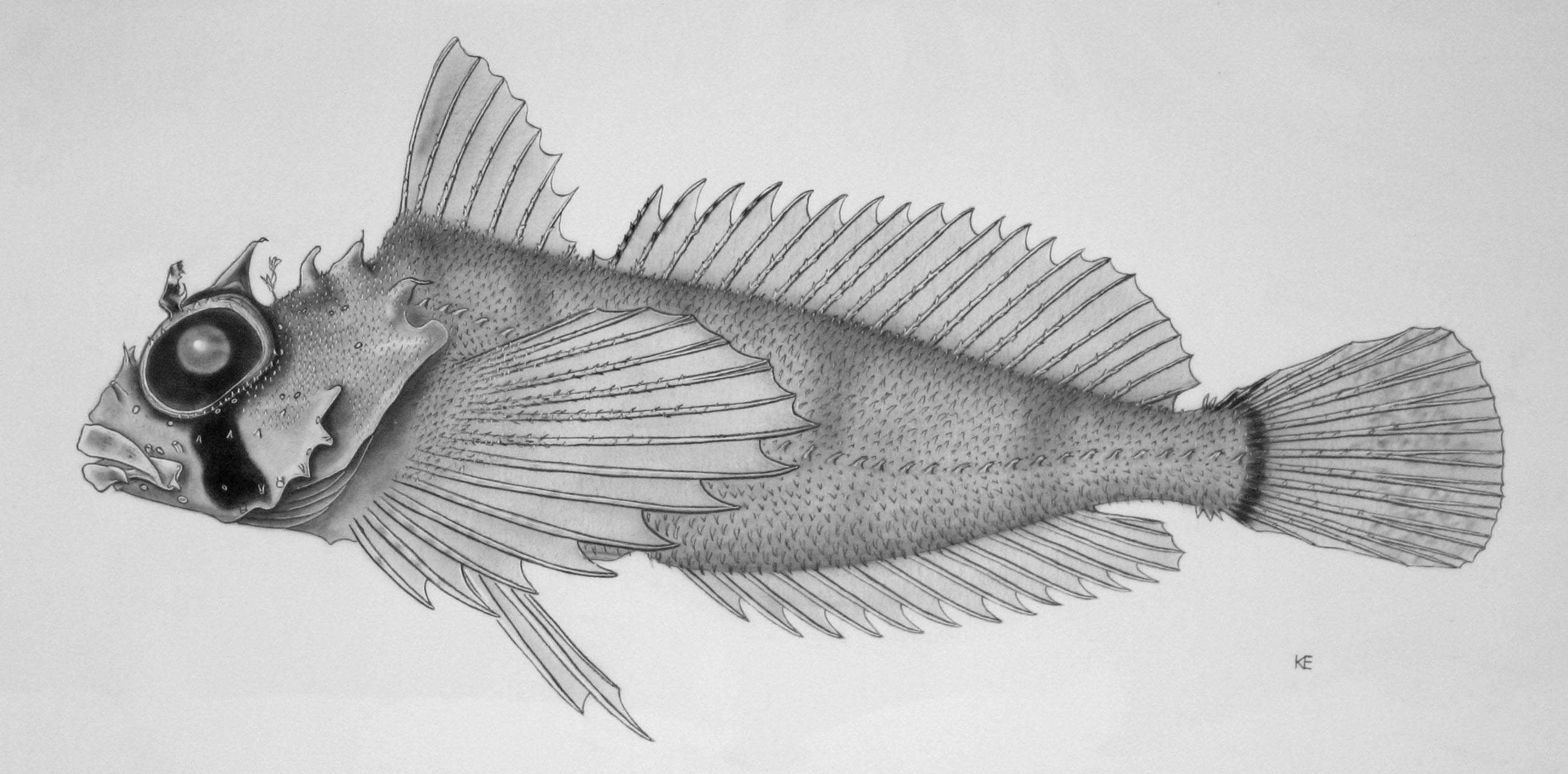

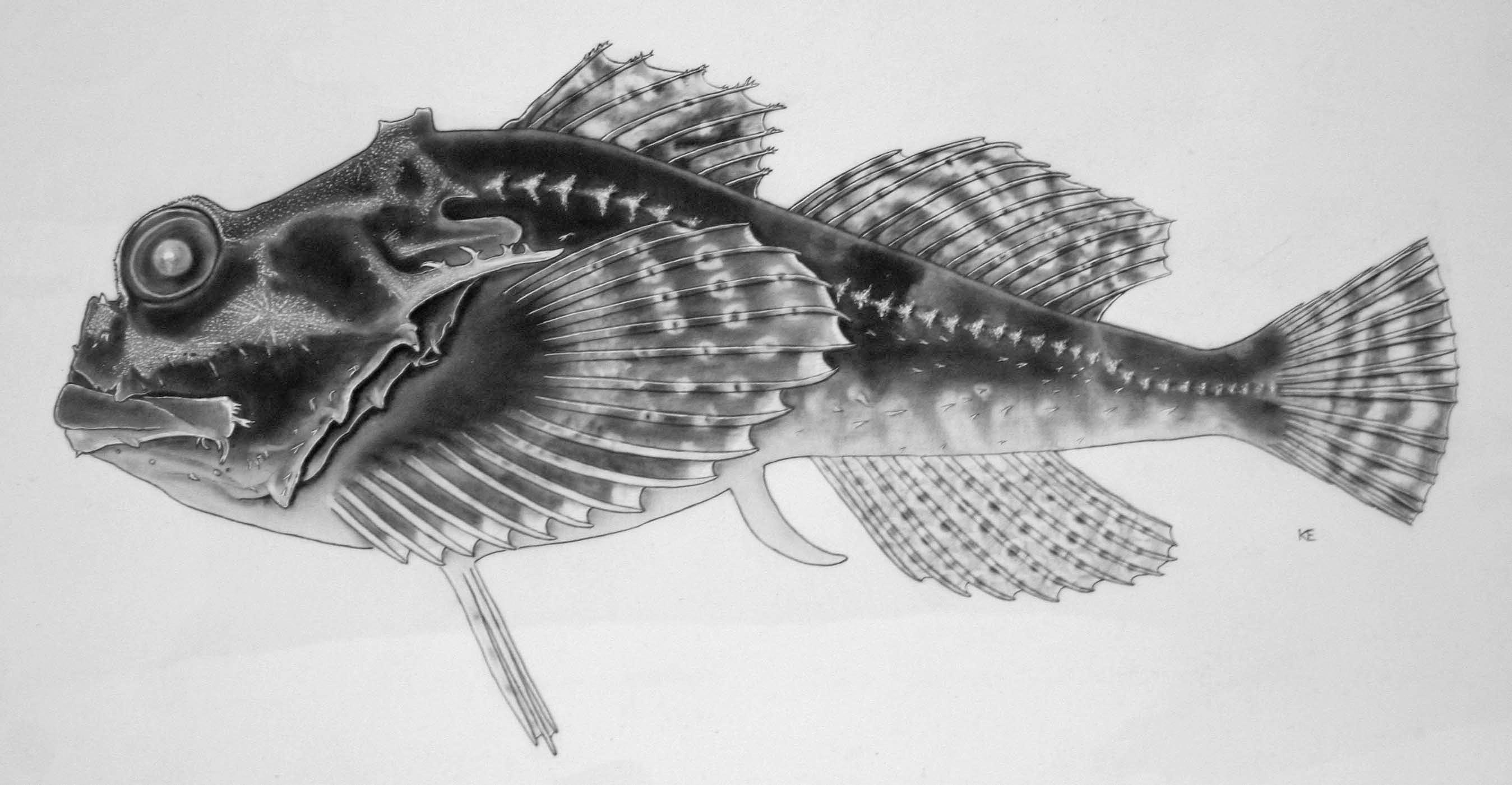

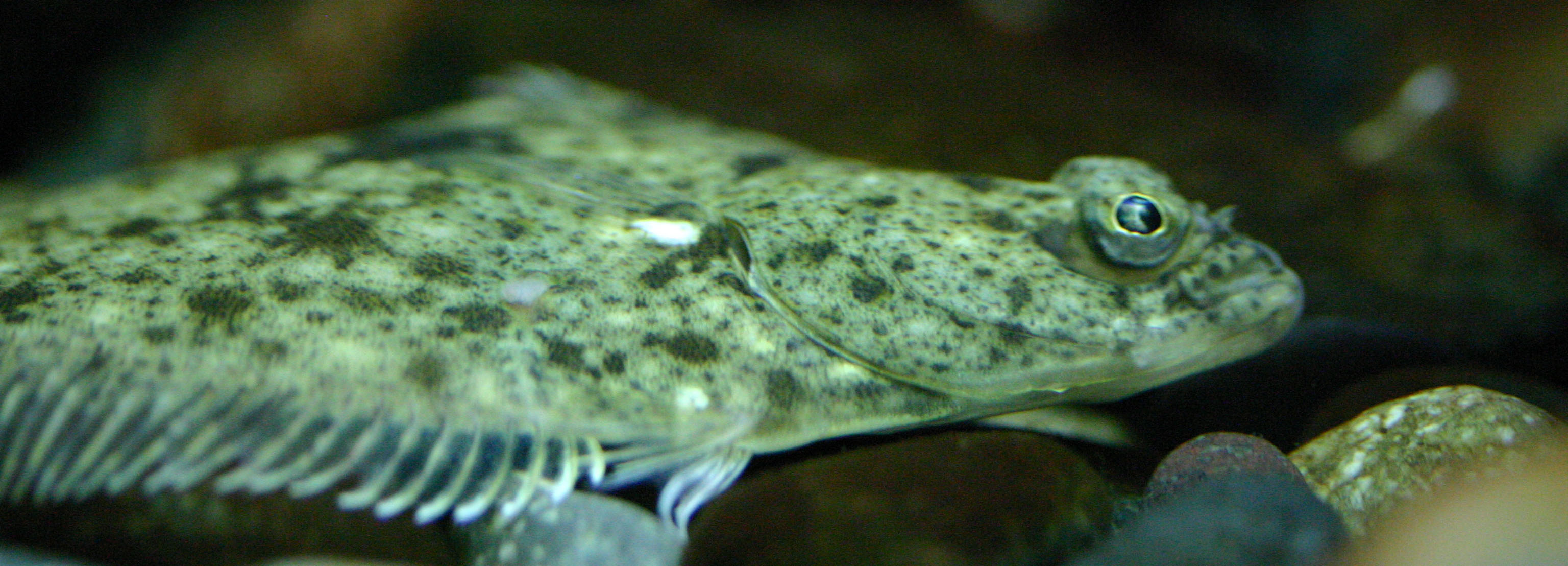

By-Catch post

When most people think about by-catch, they think of shrimp fisheries and the thousands of tons of sea life which gets caught along with shrimp. The desired species are kept, and most everything else is dumped back into the sea or onshore.

By-catch can be a great source of new specimens for museum collections. When I go out with the Department of Fisheries and Oceans on deep sea trips I am able to sample the catch and preserve what I want. Some specimens are new to BC, some are just cool – like Brown Catsharks. We keep some specimens because they have an interesting story – like the Dreamer that had swallowed a huge wad of packing tape.

By-catch from my samples and individually donated specimens also benefits other museum researchers. Melissa Frey and I carefully dissected a large copepod (a species of Pennella) that had attached to the back of the eye of a Louvar. I get the fish, the invertebrates collection gets the massive ectoparasitic copepod (I win – both in non-creepiness and biomass). Sometimes we save other parasites (flukes to leeches) from aquatic vertebrates for the “aquatic” invertebrate collection, as well as mites and ticks from reptiles, to fleas from mammals, and some funky flies (Family Streblidae) which are ectoparasites of bats. These go into the entomology collection.

This week, the entomologists returned fire with another specimen – this time from their sampling program at Hotsprings Cove, Maquinna Provincial Park. Their insect traps catch the occasional shrew, toad and salamander, and today I received this tiny Western Red-backed Salamander for the amphibian and reptile collection.

Again I win – a cute salamander for the collection and all I had to do was walk down stairs and say, “Thank you very much”. Such is the nature of museum collaboration.

Again I win – a cute salamander for the collection and all I had to do was walk down stairs and say, “Thank you very much”. Such is the nature of museum collaboration.

PEACE post

This past summer I had ‘one of those moments’ – a moment that where you are suddenly aware that you are on the brink of something special – and it happened at an unexpected place: a car rest stop.

View of the Peace River from the car rest stop.

Yes, I had this ‘moment’ while at a car rest stop, at the top of a hill, overlooking the Peace River. I was struck by the beauty of the river and surrounding area. However, the feeling was compounded by the fact that I was also about to take part in my first ‘bioblitz’.

A bioblitz is an event that takes place over a short period of time where scientists, naturalists, and volunteers attempt to identify as many species as possible in a specific area. Myself, and 5 colleagues from the Royal British Columbia Museum (RBCM), were about to join a bioblitz organized by the Biological Survey of Canada (BSC) and the Yellowstone to Yukon (Y2Y) Conservation Initiative. Over a five days period we would be joining at least 20 other participants in documenting the biodiversity of the Peace River area that lies between Hudson’s Hope and Fort St John along the Peace River. The area was chosen because 1) it is an area that would change drastically with the construction and flooding caused by the BC Hydro Site C hydroelectric dam and 2) because relatively little is known about the flora and fauna in the area. As a biology nerd, I was excited to be participating in such a large collaboration in such an important area.

The RBCM participants were Claudia Copley (Entomology Collection Manager), Darren Copley (Bird and Mammal Preparator), Erica Wheeler (Botany Collection Manager), Ken Marr (Botany Curator), and Kristiina Ovaska (Invertebrate Research Associate). The other participants included researchers from all over the province (and few from outside the province!) that work for a range of private and professional (both governmental and NGOs) organizations and businesses. However, the best part of the bioblitz was that we were joined, supported, and guided by local naturalists, land owners and First Nations.

Darren and Claudia Copley scanning the skies for birds.

Erica Wheeler collecting plant specimens with the help of a local land owner.

Kristiina Ovaska, RBCM Invertebrate Research Associate.

A collaborative field team from the RBCM, Ministry of Environment, and the local community.

Local young naturalist.

Local land owners sharing their knowledge of the area.

Through the incredible collaboration of Y2Y and BSC, researchers were connected with local First Nations, land owners, and boat owners who shared their time, knowledge, and resources – thereby, allowing researchers to visit unique and difficult to reach habitats. During the five day bioblitz we able to explore an incredible diversity of habitats and sampled wetlands, sloughs, rivers, creek slopes, cascading water seeps, rotting tree falls, and forest leaf litter.

Sampling wetlands.

Sampling along the river edge.

A stunning and unique environment along the Peace River.

I was thrilled to get to work with our Research Associate, Kristiina Ovaska, in the Peace. Not only is Kristiina an expert on terrestrial gastropods and amphibians but she is a talented photographer. Here is a small sampling of the amazing photos she took of the local biodiversity:

Caught!

Freshwater snail.

Terrestrial slug.

Spider.

In short, it was an incredible week. My feeling, my ‘moment’, at the car rest stop on the first day was more than justified. I had an amazing week learning from, and working with, incredible researchers and naturalists. However, I was most touched by the connections made with the local community and First Nations. They are a group of people that are very passionate and committed to wanting to preserve the Peace River in its current state. The habitats, the plants and animals, and the people of this place are deeply connected.

On a Dark Path post

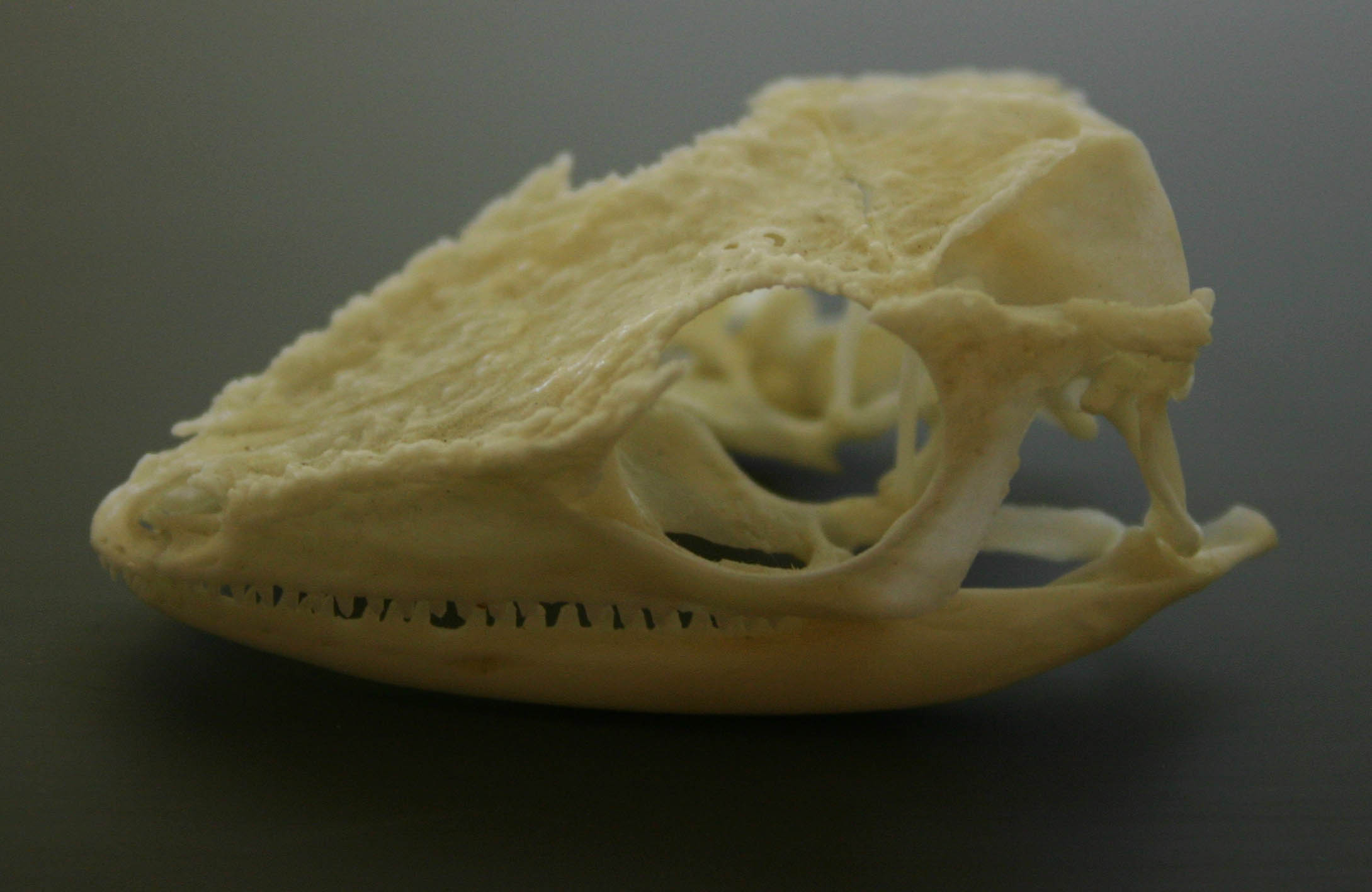

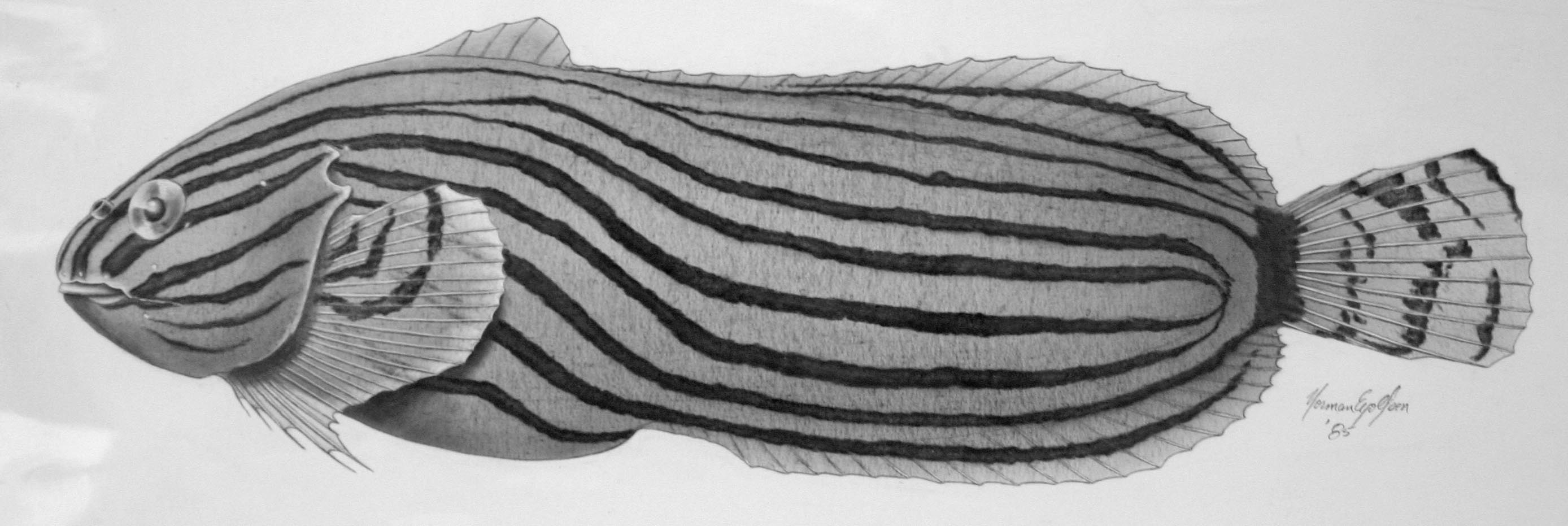

Even before I was hired as a museum curator, I was asked to write 28 species entries for some obscure fishes in Animal: the definitive visual guide to the world’s wildlife. I had to take painfully dry science and distil it into 45 or so words that anyone could understand. That set me on a dark path (cue sound effects) to the hidden vaults of museum collections and my laboratory. Who doesn’t want a laboratory full of bones?

The skeleton of an Olive Ridley Sea turtle in my laboratory.

Museum work dwells in obscurity, and a great proportion of BC citizens have no idea that RBCM staff publish academic research on par with university professors. We have an annual research day where museum staff tell other staff-members what is going on here – because we often tend to work in isolation and forget to trumpet our own successes. Short story is: Yes we do research – but to quote a friend’s daughter, “It’s not rocket science.” Some people question the value of museum research since it is not generating food, medicine or some other product essential to the Canadian economy. But not everything has an immediate practical value.

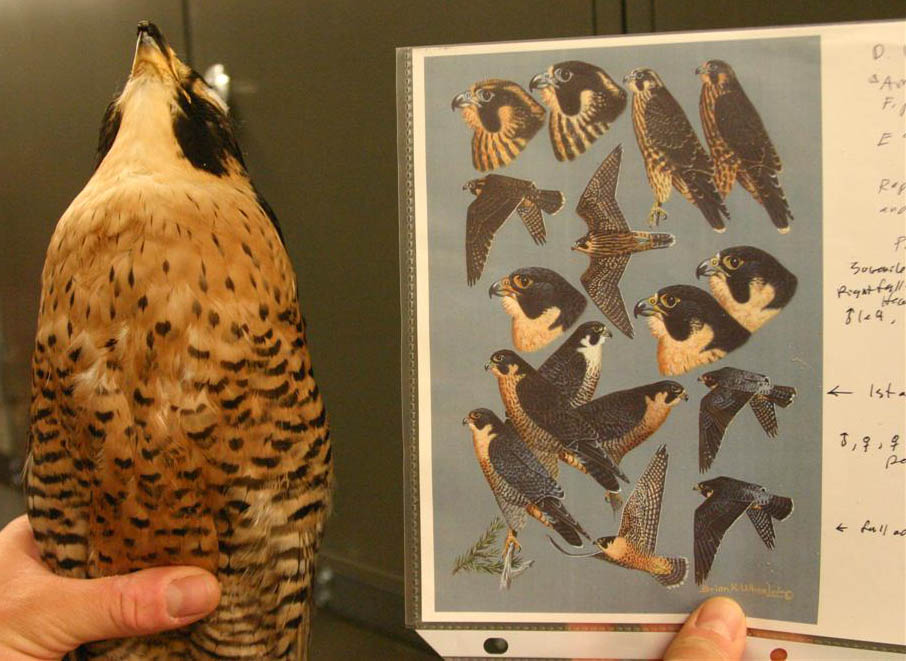

A North Pacific Argentine (Argentina sialis) from BC blasts off into academic obscurity. Modified from: http://www.forwallpaper.com/wallpaper/takeoff-launch-rocket-fire-smoke-baikonur-240897.html

People spend hours debating whether Pluto is a planet or not, and we spend billions of dollars on rockets and probes to examine our distant neighbours. We won’t colonise that planetoid/planet – so why spend so much energy debating its celestial designation? We debate it because people love to learn about new things – and let’s face it, people love a good argument.

Pure science has its own unique value – it is unlike other fields of study. If we look back, there was a time when electricity was considered a mere curiosity with no practical application. That is hilarious from a 2015 vantage point, as I bask in fluorescent light, the hum of the light’s respective ballasts in my ears, with several electronic gadgets at my fingertips. Much of what we do in museum research and collections development appears to have no practical value. We collect and study objects with no idea how they will be used by future generations. Perhaps the Louvar and Finescale Triggerfish are the vanguard to future drastic changes to the Pacific Ocean’s ecology. Perhaps not. I have no idea whether anyone will ever look at those fish again.

We commonly get accused of stamp collecting – merely trying to collect one of everything just to say we have a complete set. Perhaps my collection of Star Wars cards predisposed me to a life as a museum scientist. Now that I think of it, we actually have packs of Star Wars cards in the RBCM’s Human History collection. I wonder if the museums packages still have the horrible tasting chewing gum? But I digress…

Instead of being satisfied with one of everything in Natural History (a philatelic approach), we keep collecting. We collect year to year from different areas, males, females, young, old, eggs, tadpoles, oddities, etc., and in all Natural History disciplines, the one commonality is that we do specimen based research. We don’t have labs full of machines that go ‘ping’, unlike university biology departments – which to me look more like chemistry labs these days. But at a museum, we still have preserved specimens – plants, crabs, fish, fungi, lichen, birds, whales… This is a taxonomists playground. University researchers come to us when they need material for study (DNA, hair samples, or to make measurements from historic specimens) – just today I had a request for feather samples from White-crowned Sparrows. Museums also are as close to a time machine as you can get outside of science fiction. At museums you can hold an animal or plant collected 100 or more years ago. Nowhere else provides this sort of service to science and society.

But who cares? What is the point of discovering a new fish in BC waters? Or unravelling a species complex of beetles or stickleback? For me, the research generates knowledge for the simple pleasure of knowing stuff. I get a research paper published and maintain a publication record as a fish nerd – and that is enough for me. Do you benefit from scientific introspection (AKA navel-gazing)? I say yes.

People did well enough before the Victorian era, even though the present diversity of nature was far from understood. But ships in the 1700s and 1800s carried frenzied explorers to far corners of the world, in a grand age of biological stamp-collection. The race was on to catalogue nature and this continues even today. Without a proper understanding of species boundaries, all other branches of biological science and medical experimentation collapse. There is no sense comparing the effects of a drug on Norway Rats relative to a control group of un-medicated gerbils. It may seem simplistic to say that, but if we don’t understand species, we could be comparing quite different organisms rendering scientific results meaningless.

As a practical example of your reliance on science, try figure out what species of fish are in your local grocery store. Sure the labels says “sole”, but which one? Is that a local species? Or imported from Europe? Could one of them represent an endangered species? Are all the fish in the same tray from the same species? You may not be interested in a museum article on the identification of a single fish, or the RBCM’s contribution to DNA barcoding, but you may be ecologically conscious and want to make informed dietary decisions. Without proper identification, or if the basic taxonomy is wrong, we all flounder in ignorance. Even your grocery store choices depend on basic museum science.

Beyond practicalities on an individual level, does the museum as an organisation benefit from obscure research? Again yes. Active study maintains the institution’s reputation as research facility. It shows we are engaged, and that we continue to discover new things. The research helps build the collection – a biological library which generates even more scientific study. We stockpile museum specimens and information for the benefit of society. Museum researchers generate primary literature for academic discussion, but we also filter volumes of information to create concise content for public consumption. We bridge the gap between hard-nosed science and the hard-working public. A museum fails when it isolates collections and researchers from the public. What is the point of a museum collection if no one sees it, no one studies it, and the information is not shared.

There is no point collecting specimens only to lock them away forever.

There is no point collecting specimens only to lock them away forever.

How can you keep current with our scientific advances and collection development? Our work is available globally in scientific journals. However, peer-reviewed science is mostly held in university libraries, and online access to scientific articles can be an expensive cure for insomnia. We also make our work available in a more casual format. You can visit in person and stroll through our galleries, take a collection tour, view one of our travelling exhibits, and we are also just a click away with blog articles, museum magazine articles, and web portal content. There are many ways the RBCM bridges the gap between pure academic research and the interests of every-day museum visitors. You don’t expect to learn about Pluto at the RBCM, but you do come here to learn about British Columbia and connect with our vibrant research community. We are irrelevant without you.

Clean Baleen post

![Whale-005[1]](http://staff.royalbcmuseum.bc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Whale-0051.jpg) On April 20th, 2015, a 9 meter Grey Whale washed up on Long Beach, Vancouver Island. On April 23rd, a small army of researchers and volunteers performed a necropsy and cleaned most of the meat off the bones. The bones are now buried and once clean, will be added to the Royal BC Museum’s research collection.

On April 20th, 2015, a 9 meter Grey Whale washed up on Long Beach, Vancouver Island. On April 23rd, a small army of researchers and volunteers performed a necropsy and cleaned most of the meat off the bones. The bones are now buried and once clean, will be added to the Royal BC Museum’s research collection.

One item that did not stay with the whale’s bones was its baleen. Baleen is essentially the same epidermal material as your fingernails and acts as a sieve to allow the whale to strain water from edible morsels like crustaceans. You can see the baleen in the mouth in both of these photos, although in the second photo, most baleen had already been removed. Several organisations wanted material for public display, and so I decided to experiment with a method of slow dehydration to preserve strips of baleen.

The baleen itself was removed right down to the gum-line along the jaw – and it pulled out very cleanly. I left cut sections of baleen at room temperature in a standard picnic cooler overnight. The next day I washed the sand and other debris out of the baleen and then immersed each piece in 95% ethanol. The pieces stayed in ethanol for 5 months (almost to the day), with the hope that the alcohol would draw out water from the remaining tissues.

To make a short story long: it worked.

The baleen was removed from the ethanol and left to air dry over a few days. I had thought I would have to use heavy nails to nail each piece to a board to prevent the tissue from curling, but it proved unnecessary. The gum-line did curl slightly, but not enough to ruin the look of each piece.

The baleen was removed from the ethanol and left to air dry over a few days. I had thought I would have to use heavy nails to nail each piece to a board to prevent the tissue from curling, but it proved unnecessary. The gum-line did curl slightly, but not enough to ruin the look of each piece.

In these three photos you can see the baleen in lingual view (the side facing the tongue), labial (the side facing the lip) and the underside of the gumline which shows fine slots and canals which housed the cells producing baleen tissue.

In these three photos you can see the baleen in lingual view (the side facing the tongue), labial (the side facing the lip) and the underside of the gumline which shows fine slots and canals which housed the cells producing baleen tissue.

Now the baleen chunks can be left at room temperature and over time the slight alcohol-fishy-smell should dissipate. Once permits are secured for each organisation, I’ll be able to ship the sections of baleen to local nature centers so that people can see first hand how fascinating baleen really is.

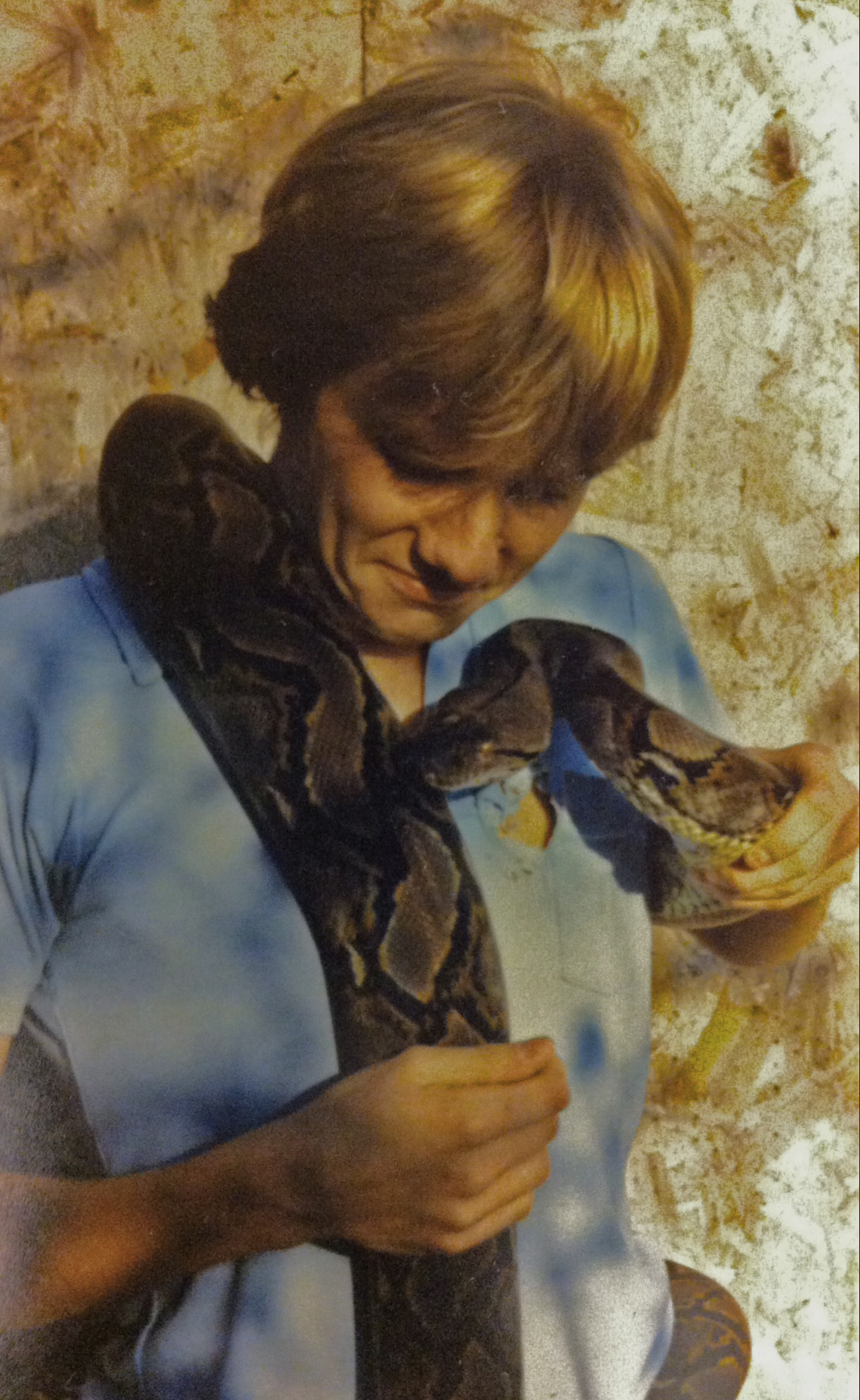

Parents and Mentors post

I am sure my parents just shook their heads when I started bringing home reptiles and amphibians, but they did not discourage me. That is what matters. They suffered the smells that wafted from the various cages, had to deal with escaped snakes, lizards and newts (newts always were found dried-out in mid-stride…), and took me to the hospital after a large python tried to kill me. But I don’t think they had any idea that my interest in animals would lead to a worthwhile career.

Chasing snakes and frogs in the Interlake of Manitoba (Norris Lake).

Chasing snakes and frogs in the Interlake of Manitoba (Norris Lake).

In winter my Dad took me out to buy goldfish, and in summer, we’d go to nearby ponds to catch frogs to feed to my pet snakes. We’d also do our annual pilgrimage to the snake dens at Narcisse, in Manitoba’s interlake region. I was a lucky kid. My parents let me vanish into swamps with ice cream buckets to hunt frogs and snakes all day. I wonder what proportion of kids today are so free. Perhaps there is a game now where kids get to catch and keep frogs and snakes. Sim-Terrarium anyone?

Granite Lake, west of Kenora, Ontario – one of many snakes I caught as a kid, along with Jamie Coyle and my brother Ian.

Granite Lake, west of Kenora, Ontario – one of many snakes I caught as a kid, along with Jamie Coyle and my brother Ian.

These memories came flooding back because my friend Lea also has started her son on a similar path. Lea has allowed her son to have a pet praying mantis and a chamaeleon… who knows what is next. My guess is a Bearded Dragon will be next or a Leopard Gecko. A few decades from now perhaps he will have my job here at the RBCM.

Canada goose bones from the RBCM collection (RBCM 16187).

Canada goose bones from the RBCM collection (RBCM 16187).

Last week I helped a young lad identify a bone he had found. Obviously he had ideas about the bone’s identity, and had wondered whether it was a skull or not. But after a short visit to the Ornithology collection, I was able to show that the bone he found was the sternum from a Canada Goose. Then I explained where muscles attached that allowed the bird to flap its wings – and how to find the same muscles on the next chicken or turkey they roasted. Perhaps he will become a prominent comparative anatomist. And he too will thank his parents for helping foster an interest in nature.

Parents – try not to freak out when your kid brings one of these home.

Parents – try not to freak out when your kid brings one of these home.

Perhaps I am to these kids, what Bill Preston was to me. Bill was the herpetologist at the Manitoba Museum, and as the author of the Amphibians and Reptiles of Manitoba, he made a great impression on me. Bill’s book (now very worn) kept me interested in amphibians and reptiles and I eventually replaced him at the Manitoba Museum as their Vertebrate Zoologist. If we spark the imaginations of kids and get them outside to build our next generation of naturalists, who knows where they will end up. I was thrilled to see so many kids at the RBCM’s two commemorative beach walks this summer – my youngest daughter included.

Anna and I during the June 14th beach seine at Willows Beach (photo by Chris O’Connor, RBCM)

Anna and I during the June 14th beach seine at Willows Beach (photo by Chris O’Connor, RBCM)

We also hosted some amazing kids this year at our Gold Rush day camps. They certainly will remember the vats and jars of pickled specimens in my lab. These kids are the future scientists, politicians, lawyers, entrepreneurs, and regardless of which career they choose (we can’t all be lucky enough to work at a museum), kids need exposure to nature. It doesn’t matter if kids like lichen, liverworts, lepidoptery, or leopard frogs, our job as parents and mentors is to make sure today’s kids appreciate and value their connection to the earth.

Learning about soil (photo by my wife, Jeannette Bedard).

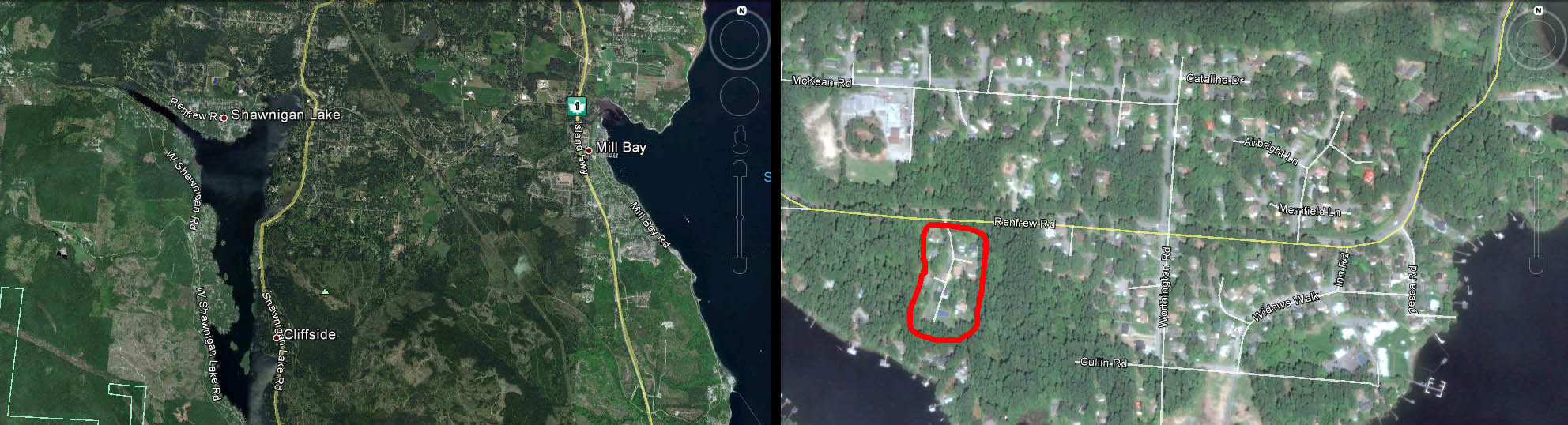

My favourite invasive species is still on the move. It is August 24th, 2015, and I just received photos confirming the presence of European Wall Lizards at Shawnigan Lake, British Columbia. A few weeks back, I was chatting with Rod Park, a cameraman with CHEK news. He said he had lizards at his house in Shawnigan Lake. The behaviour he described sounded suspiciously like that of the Wall Lizard. Alligator Lizards (our native lizard on Vancouver Island) are far more secretive and not so likely to be found in numbers in urban environments.

Today I received photos taken by Rod’s son Sterling, and even though the lizards did not cooperate – the photos are certainly good enough to show that they do indeed have European Wall Lizards. The lizards appeared about a year ago, and now sightings are a regular occurence. This is typical – one or two lizards reproduce, and the population explodes to 50 or more lizards in a few years. Some gardens on the Saanich Peninsula have hundreds of Wall Lizards – this species is highly invasive.

Photo by Sterling Park, August 2015

Photo by Sterling Park, August 2015

Who knows how they made the jump to Shawnigan Lake – as eggs in a plant pot? Adult stow-aways? Intentional release? We may never know. This record certainly is a surprise – there are a few records from Mill Bay, but none as far west as Shawnigan Lake. Please be careful when moving hay, horse trailers, plants and soil – you never know what else you are carrying. Wall Lizards don’t need any more help – they have gone far enough.

Photo by Sterling Park, August 2015

Photo by Sterling Park, August 2015

Anyone reading this in the Shawnigan Lake area — please email any sightings to me here at the RBCM so we can keep tabs on the rate of spread in your region. This summer we also had our first record in North Vancouver, and so I wonder where they are next to appear? This species could spread far down the Pacific coast and disturb native wildlife as it spreads. Wall Lizards are an unwelcome addition to our fauna and there seems to be no way to eliminate them from Vancouver Island now.

Photo by Sterling Park, August 2015

Since they are cannibalistic, I could imagine they’d have no problem eating (or at least killing) hatchling Sharp-tailed Snakes and Sharp-tail Snake eggs, or newborn garter snakes. They probably can eat newborn Northern Alligator Lizards, and every sunny day, Wall Lizards in BC must eat hundreds of thousands of insects and spiders. The unique place we call British Columbia is being hit hard by exotic species. You can make a difference. Help prevent the spread of these invasive lizards.

My contact info:

Gavin Hanke Curator, Vertebrate Zoology | Archives, Collections & Knowledge

675 Belleville Street, Victoria, BC Canada V8W 9W2

T 250 952-0479 | F 250 387-0534 (who sends faxes anymore?)

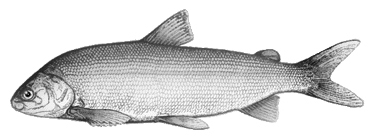

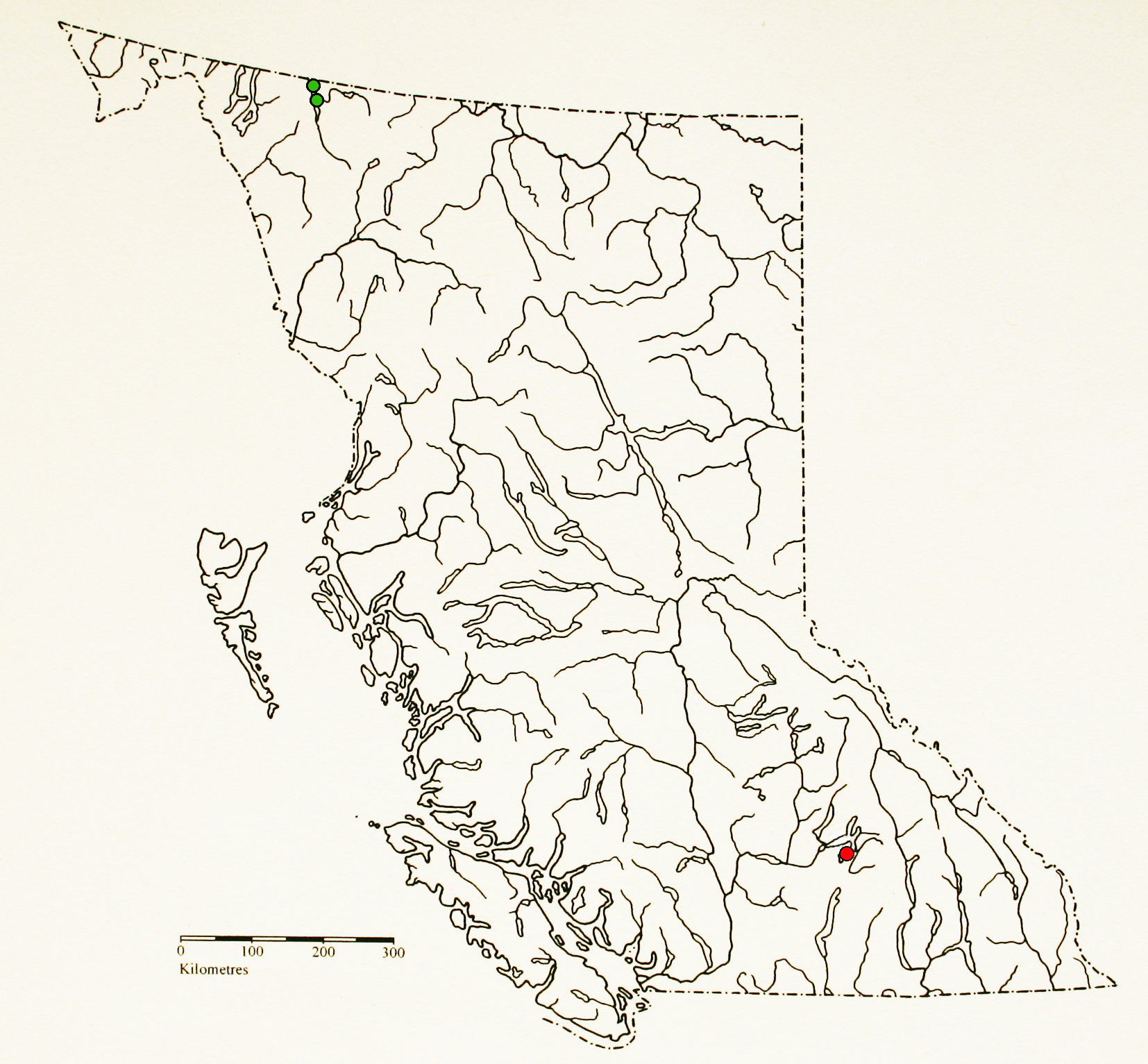

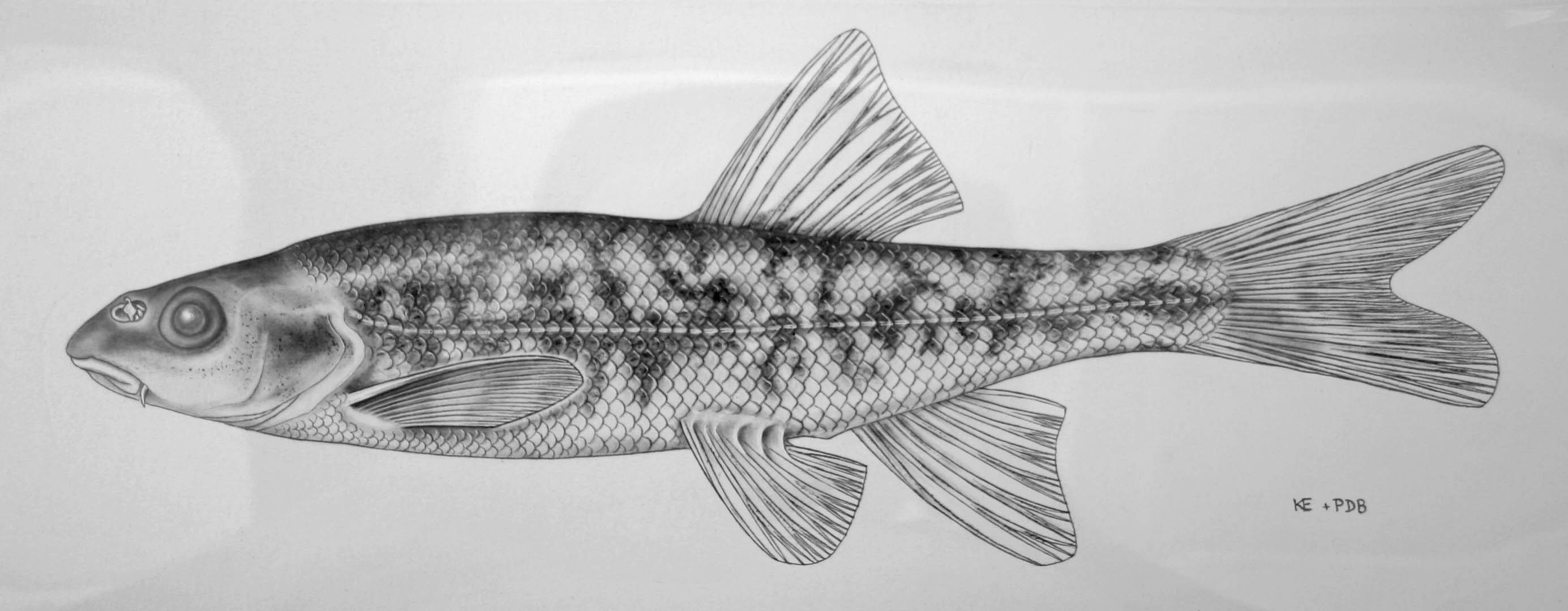

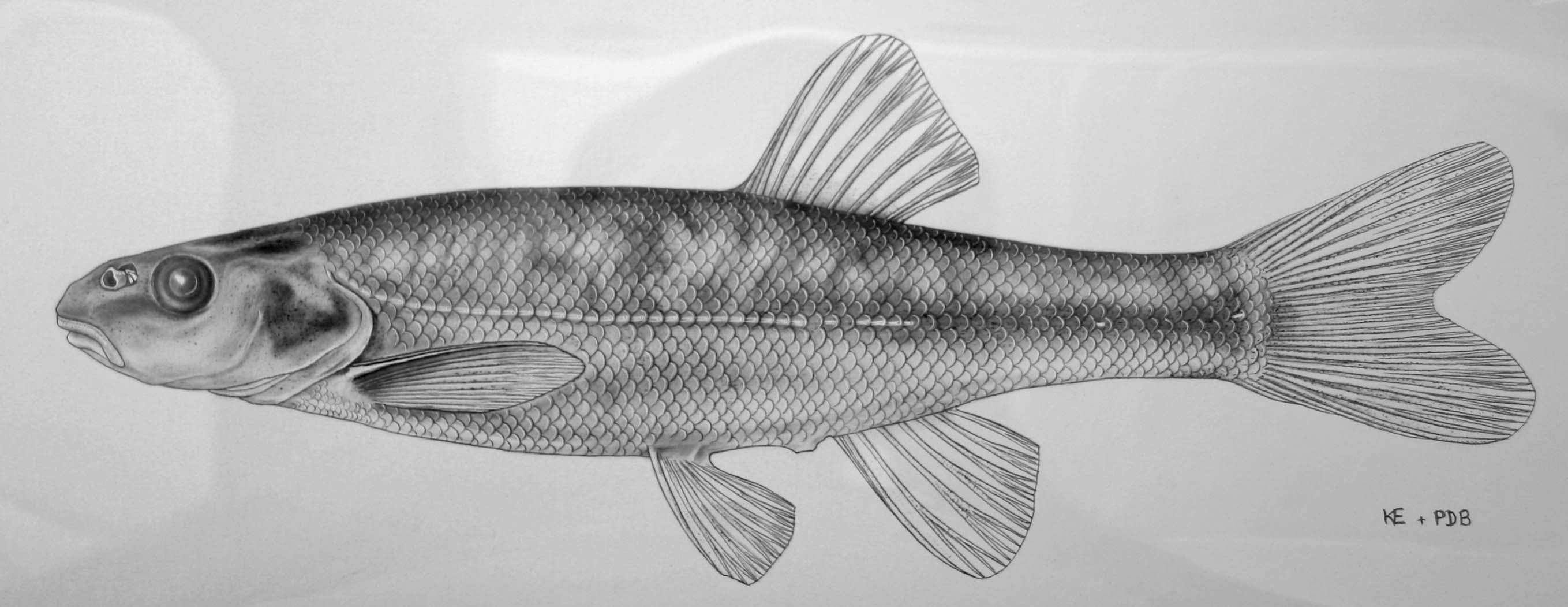

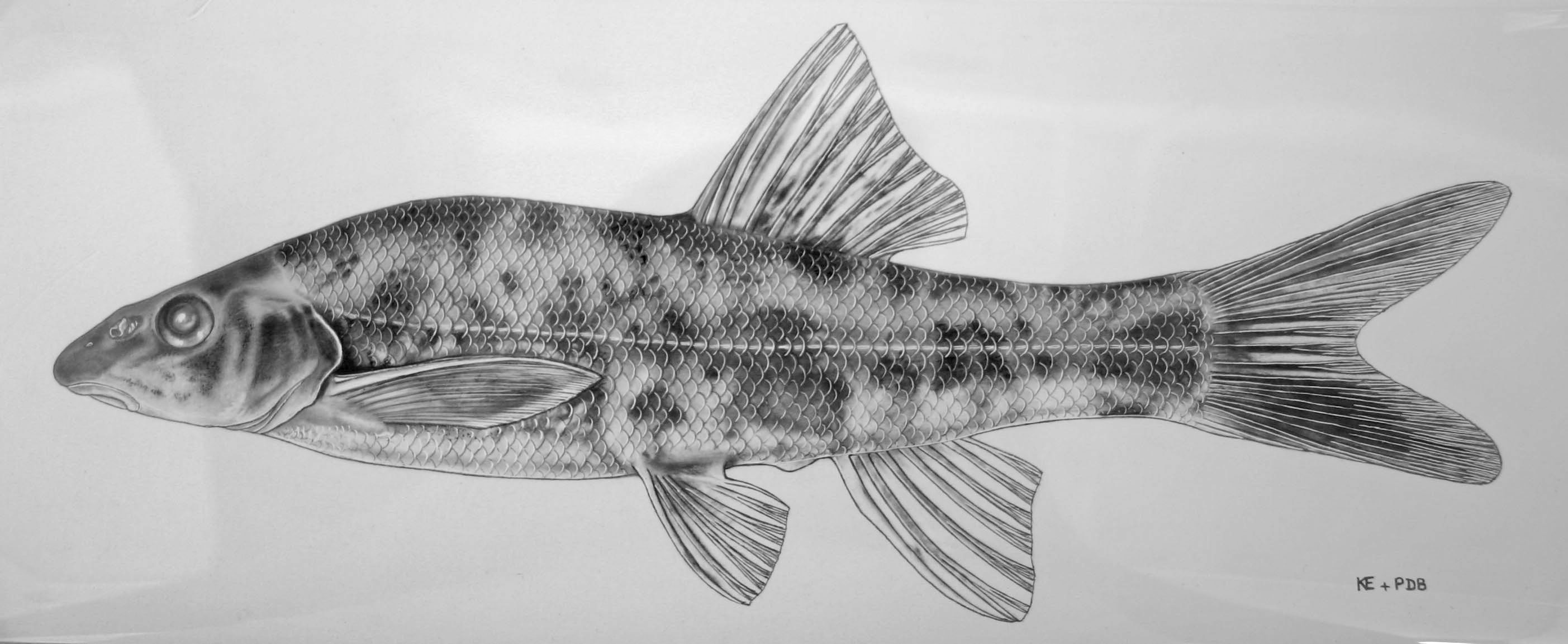

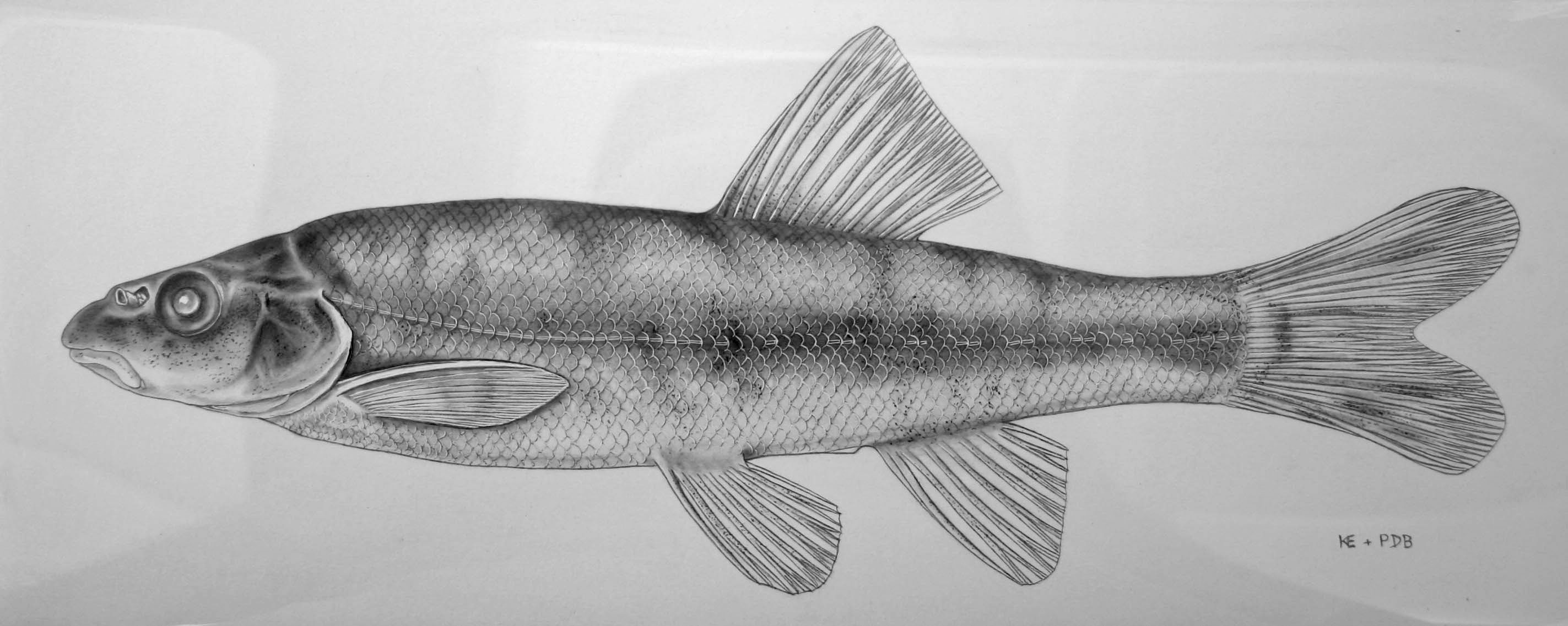

We rarely get a chance to sample freshwater fishes in BC, especially in the extreme north and rely on voucher specimens from other researchers to build our collection. One of the most rarely collected fishes is the Broad Whitefish (Coregonus nasus). Usually I talk about southern fishes invading northward, or exotic fishes released by people, but the Broad Whitefish is an example of an Arctic fish that just barely ranges into British Columbia, and we had six listed for the RBCM collection:

RBCM 000-00155-003; a single fish from off Canoe Creek mouth, Shuswap Lake, collected in 1979.

RBCM 979-11202-001; a single fish from Nisutlin Bay, Teslin Lake, Yukon, collected in 1979.

RBCM 979-11208-001; a single fish from just north of Teslin on east side of Teslin Lake, Yukon, collected in 1979.

RBCM 986-00295-001; two fish with no locality data, although they were collected the same day by the same collector as RBCM 990-00170-001.

RBCM 990-00170-001; a single fish from Kugmallit Bay, Beaufort Sea, collected in 1980.

Only one of our specimens was caught within British Columbia, and this single fish is from Shuswap Lake off the mouth of Canoe Creek. If you check Don McPhail’s magnum opus on Freshwater Fishes of British Columbia, there is no record of Broad Whitefish stocked in Shuswap Lake. Something so obvious as a Broad Whitefish in Shuswap Lake should have thrown up warning flags, but the specimen in the RBCM collection has sat since November 2000 and had not been re-examined. One of the jobs of a museum curator is to periodically look for probable mistakes in specimen identification, and correct identifications if possible.