We rarely get a chance to sample freshwater fishes in BC, especially in the extreme north and rely on voucher specimens from other researchers to build our collection. One of the most rarely collected fishes is the Broad Whitefish (Coregonus nasus). Usually I talk about southern fishes invading northward, or exotic fishes released by people, but the Broad Whitefish is an example of an Arctic fish that just barely ranges into British Columbia, and we had six listed for the RBCM collection:

RBCM 000-00155-003; a single fish from off Canoe Creek mouth, Shuswap Lake, collected in 1979.

RBCM 979-11202-001; a single fish from Nisutlin Bay, Teslin Lake, Yukon, collected in 1979.

RBCM 979-11208-001; a single fish from just north of Teslin on east side of Teslin Lake, Yukon, collected in 1979.

RBCM 986-00295-001; two fish with no locality data, although they were collected the same day by the same collector as RBCM 990-00170-001.

RBCM 990-00170-001; a single fish from Kugmallit Bay, Beaufort Sea, collected in 1980.

Only one of our specimens was caught within British Columbia, and this single fish is from Shuswap Lake off the mouth of Canoe Creek. If you check Don McPhail’s magnum opus on Freshwater Fishes of British Columbia, there is no record of Broad Whitefish stocked in Shuswap Lake. Something so obvious as a Broad Whitefish in Shuswap Lake should have thrown up warning flags, but the specimen in the RBCM collection has sat since November 2000 and had not been re-examined. One of the jobs of a museum curator is to periodically look for probable mistakes in specimen identification, and correct identifications if possible.

Here is my Key to help identify whitefishes, and is a combination of identification keys by McPhail (2007), Wydoski and Whitney (2003), Nelson and Paetz (1992), Scott and Crossman (1973), McPhail and Lindsey (1970). The numbers in the key in brackets allow you to backtrack if you made a mistake.

Choice 1a – single flap of skin between front and rear openings of nostrils, snout narrow and somewhat pointed, gill rakers stout and short – go to 2

Choice 1b – two flaps of skin between front and rear openings of nostrils, snout width tapers gradually or is blunt, gill rakers elongate but may be shorter – go to 4

Choice 2a (1a) – small spots (parr marks) retained in adults, snout blunt and rounded, base of adipose fin less than eye diameter, 18 to 20 scales around the base of the tail, lateral line scales same size as adjacent body scales:

PYGMY WHITEFISH (Prosopium coulterii) – found in the Fraser, Columbia, Mackenzie, Yukon, North Coast, and Central Coast drainages. Because parr marks retained as adults, Pygmy Whitefish commonly mistaken for juveniles of Mountain Whitefish.

Choice 2b (1a) –lateral line scales are noticeably smaller than adjacent body scales, snout pointed when viewed from above – go to 3

Choice 3a (2b) – base of adipose fin less then the diameter of eye, snout pinched and slightly pointed, gill rakers short and stout, scales on flank with darker margin:

ROUND WHITEFISH (Prosopium cylindraceum) – found in the Mackenzie, Yukon, and North Coast drainages.

Choice 3b (2b) – adipose fin about 1.5 times the eye diameter, scales on flank evenly pigmented without darker margin, snout variable from ones with evenly tapered convex snouts to those with longer and thinner snouts offset from the general profile of the head:

MOUNTAIN WHITEFISH (Prosopium williamsoni) – found in the Fraser, Columbia, Mackenzie, North Coast, and Central Coast drainages.

Choice 4a (1b) – mouth extremely large and almost as wide as head, jaws with fine teeth, and the jaws appear squared when viewed from top, snout flattened and superficially pike-like, lower jaw extends beyond upper jaw, body cylindrical and elongate:

SHEEFISH (Stenodus leucichthys) – found in the Mackenzie and Yukon drainages.

Choice 4b (1b) – snout small and narrow and not as wide as head, lower jaw may project ahead of upper jaw, body deep and compressed – go to 5

Choice 5a (4b) – tip of snout flat to overhung – go to 6

Choice 5b (4b) – tip of snout pointed, lower jaw may protrude beyond upper jaw – go to 7

Choice 6a (5a) – tail fin shallowly forked, adipose fin nearly the same size as eye, upper jaw far longer than deep, head tapers back towards dorsal fin (deepest part of body at dorsal fin origin):

LAKE WHITEFISH (Coregonus clupeaformis) – found in the Fraser, Columbia, Mackenzie, Yukon, North Coast, and Central Coast drainages.

Choice 6b (5a) – tail fin deeply forked, adipose fin significantly larger than eye, upper jaw is as deep as it is long, body profile raises abruptly from head giving a hump-backed appearance (deepest part of body well-ahead of dorsal fin):

BROAD WHITEFISH (Coregonus nasus) – found in Teslin Lake, Yukon.

Choice 7a (5b) – upper jaw does not reach level with the leading edge of eye or only barely reaches eye level, pelvic fins positioned nearly level with the dorsal fin origin (i.e., the equivalent distance from the snout to the pelvic origin, measures back from the pelvic origin to the narrow part of the caudal peduncle ahead of the origin of the fulcral rays of the tail):

LEAST CISCO (Coregonus sardinella) – known only from Atlin, Teslin and Swan lakes in the Yukon drainage in British Columbia.

Choice 7b (5b) – upper jaw longer, reaching at least the level of the pupil, pelvic fin origin positioned noticeably behind the dorsal fin origin (i.e., the equivalent distance from the snout to the pelvic origin, measures back from the pelvic origin to a point behind the origin of the fulcral rays of the tail) – go to 8

Choice 8a (7b) – deepest part of body ahead of the dorsal fin origin (slightly hump-backed appearance), upper and lower jaws usually equal such that neither protrude, dorsal margin of upper jaw fairly straight, pelvic fin origin positioned mid-way along the length of the dorsal fin base:

ARCTIC CISCO (Coregonus autumnalis) – found in the Mackenzie (in British Columbia known only from a spawning run in the Liard River).

Choice 8b (7b) – deepest part of body at the dorsal fin origin (not hump-backed), upper jaw reaches back level with the pupil of eye, dorsal margin of upper jaw curved, pelvic fins positioned well-behind the dorsal fin origin:

LAKE CISCO (Coregonus artedi) – found in the Mackenzie River system in British Columbia.

NOTE: Lake Ciscoes are highly variable within and between river/lake systems. Within lakes, there may be bottom dwelling and open water populations that evolve distinctive body features and this complexity makes species identification difficult. Molecular data suggest that populations of Coregonus artedi evolved a normal, long-jawed form and a short-jawed form within many lakes. This short jawed form usually gets called Coregonus zenithicus because fisheries biologists considered the short jawed form a distinct species that dispersed from the Laurentian Great Lakes. Molecular evidence suggests that multiple independent origins of “zenithicus-like” short-jawed forms evolved across Canada from separate populations of typical Coregonus artedi. The lumping of all short-jawed forms from all lakes across Canada obscures true evolutionary relationships among whitefishes.

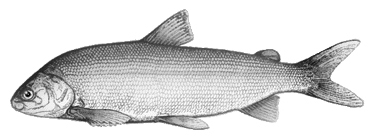

RBCM 000-00155-003, from off the mouth of Canoe Creek, Shuswap Lake, collected June 12, 1979 (I was in grade 6). It was originally labeled as Salmo sp., and re-identified as Coregonus nasus in November, 2000. What do you think? Does it match the description or the drawing from Scott and Crossman (1973) (below)?? Even Step 1 in the key eliminates this fish as a Coregonus species – RBCM 000-00155-003 has one flap of skin separating the anterior and posterior nasal openings. Lateral line scales are a bit smaller than adjacent body scales, the snout is pointed when viewed from above, and the base of the adipose fin is significantly longer than the eye diameter. Oh well, problem solved. – it is a Mountain Whitefish (Prosopium williamsoni), from well-within the known range for that species.

RBCM 000-00155-003, from off the mouth of Canoe Creek, Shuswap Lake, collected June 12, 1979 (I was in grade 6). It was originally labeled as Salmo sp., and re-identified as Coregonus nasus in November, 2000. What do you think? Does it match the description or the drawing from Scott and Crossman (1973) (below)?? Even Step 1 in the key eliminates this fish as a Coregonus species – RBCM 000-00155-003 has one flap of skin separating the anterior and posterior nasal openings. Lateral line scales are a bit smaller than adjacent body scales, the snout is pointed when viewed from above, and the base of the adipose fin is significantly longer than the eye diameter. Oh well, problem solved. – it is a Mountain Whitefish (Prosopium williamsoni), from well-within the known range for that species.

Drawing of a Broad Whitefish (C. nasus) from Scott and Crossman (1973).

Drawing of a Broad Whitefish (C. nasus) from Scott and Crossman (1973).

Broad Whitefish have a deep compressed body, and the body profile raises abruptly behind head giving a hump-backed shape (weight forward – in flyfishing terms). This species also is noted for its short, deep upper jaw bone, and short, blunt snout which overhangs the mouth. The head is small relative to the body. The lateral line is straight and the body is covered with large cycloid scales. Broad Whitefish are dusky to nearly black on the back, which blends to silvery sides and a pale yellow-white belly. The head and gill covers may have fine dusky freckles. Fins are dusky to black in adults, the pectoral and anal fins may have blue to purple iridescence, and fins of young individuals are pale and translucent. Young Broad Whitefish also lack spots (parr marks), unlike young Mountain Whitefish which have spotted bodies like juvenile salmon. Broad Whitefish grow to 86 cm.

The diet of Broad Whitefish in Teslin Lake shows they are bottom-feeders. They eat caddisfly larvae, midge larvae and pupae, waterboatmen, snails and fingernail clams, amphiopds, and zooplankton. Larval fish and fish eggs may also be eaten. Young Broad Whitefish take copepods, cladocera and midge larvae, and graduate to larger items later in the first summer.

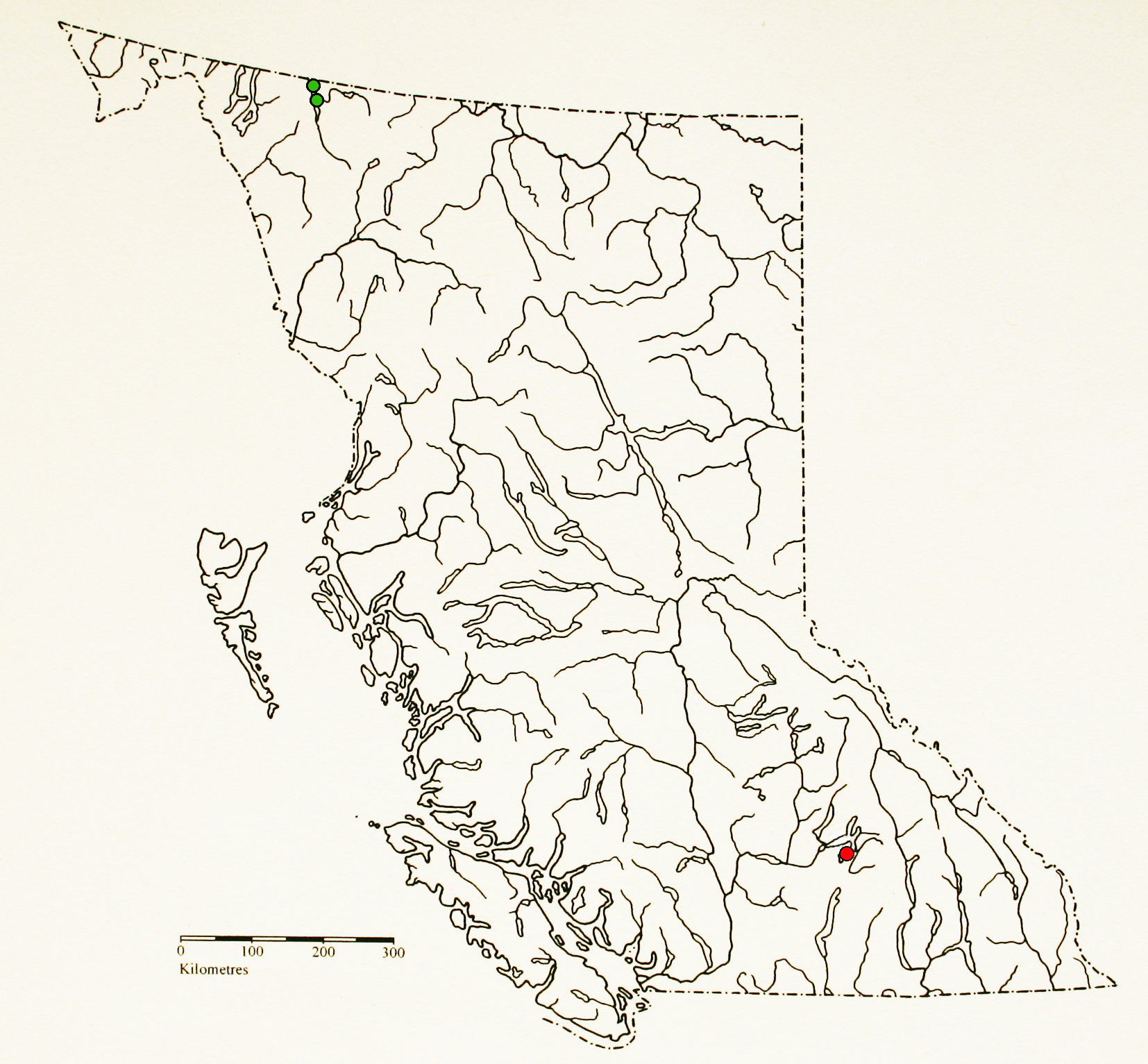

Globally, Broad Whitefish are found from the Baltic Sea, and Norwegian Sea, east across Russian Arctic to the Kuskowim River, the Yukon River system in Alaska, and other coastal streams and lakes draining into the Bering Sea, Chukchi Sea, and Beaufort Sea. They are also known from the Mackenzie River and Perry River drainages in Nunavut. In BC, Broad Whitefish are restricted to Teslin Lake and its tributaries in the Yukon River drainage. This represents the southern-most limit of the species’ natural range in North America.

Green dots indicate localities listed by McPhail 2007; the red dot indicates the location where RBCM 000-00155-003 was collected in Shuswap Lake.

Green dots indicate localities listed by McPhail 2007; the red dot indicates the location where RBCM 000-00155-003 was collected in Shuswap Lake.

Broad Whitefish are said to be common in rivers rather than lakes, but also are found in estuaries, rarely venturing far along Arctic coastal areas. Broad Whitefish are tolerant of murky water, but also will be found in clear lakes or streams, and as their hunched-over body shape suggests, the species is oriented towards the river or lake bottom rather than the surface or open water. Broad Whitefish are known to make extensive migrations, but the population in BC is lacustrine and presumably, movements are restricted to spawning runs, movements for feeding, and perhaps retreat to deeper water to overwinter. Fish in Teslin Lake are caught in less than 10 meters depth in summer, and this probably reflects feeding habitat during the productive summer season. Yearling Broad Whitefish also occupy shallow water, as do young-of-the-year, and move to the shelter of any structure or headlands when waves pound the shoreline, and to deeper water in winter.

Broad Whitefish move from lakes to tributary streams to spawn in October to November, but this behavior may begin as early as July to August in the far north. They probably spawn under ice cover when water is near 0°C. Broad Whitefish may spawn in streams which drain from a lake, or they may head upstream in tributaries which feed into a lake to find suitable gravel substrate for egg deposition. We do not know the exact nature of Broad Whitefish spawning in Teslin Lake. Females can carry up to 51,000 eggs, and in the Arctic Red River, females can outnumber males by 15 to one, and they spawn at night. Like other whitefish, Broad Whitefish scatter their eggs over the substrate and abandon their offspring. Because of energetic constraints in the north, Broad Whitefish may spawn every other year, although a good proportion will spawn in consecutive years. Shortly after spawning, adults move back to their resident lake (or downstream to another lake) for winter refuge. Some Broad Whitefish use the same over-wintering areas in consecutive years. Eggs have been incubated for 59 days at 4°C, and hatched as temperatures were elevated to 7°C; this temperature increase probably simulated spring’s slightly warmer runoff to the developing embryos. In the wild, eggs probably hatch around ice breakup in spring. Broad Whitefish are known to live at least 35 years.

For comparison, here’s the head of a real Broad Whitefish from the Beaufort Sea (RBCM 990-00170-001). The snout profile and the shape of the upper jaw (maxilla) are significantly different – and yes – just to be picky, I checked and RBCM 990-00170-001 has two flaps separating the anterior and posterior nasal opening.

For comparison, here’s the head of a real Broad Whitefish from the Beaufort Sea (RBCM 990-00170-001). The snout profile and the shape of the upper jaw (maxilla) are significantly different – and yes – just to be picky, I checked and RBCM 990-00170-001 has two flaps separating the anterior and posterior nasal opening.

While whitefishes in Canada have been studied intensively, there is still much to learn. There probably are new species to discover (keep your eye on Coregonus zenithicus (Shortjaw Cisco) – it may include several cryptic species). Perhaps with concerns over climate change and with increased attention to northern ecosystems, Canadian whitefish will get the attention they deserve. The single fish identified as a Broad Whitefish from Shuswap Lake, far south of the native range of Broad Whitefish, represents a misidentified Mountain Whitefish (Prosopium williamsoni). In BC, Broad Whitefishes are restricted to Teslin Lake and its tributaries. I think I should bug my friend Kim Howland, she likes whitefish, and suggest she spend some time at Teslin Lake to get more specimens for the museum collection. The RBCM officially has no Broad Whitefish from BC.

Sources:

Howland et al. 2009, McPhail 2007, Wydoski and Whitney 2003, Mecklenburg et al. 2002, Maitland 2000, Nelson and Paetz 1992, Wheeler 1978, Scott and Crossman 1973, McPhail & Lindsey 1970, Carl et al. 1967.