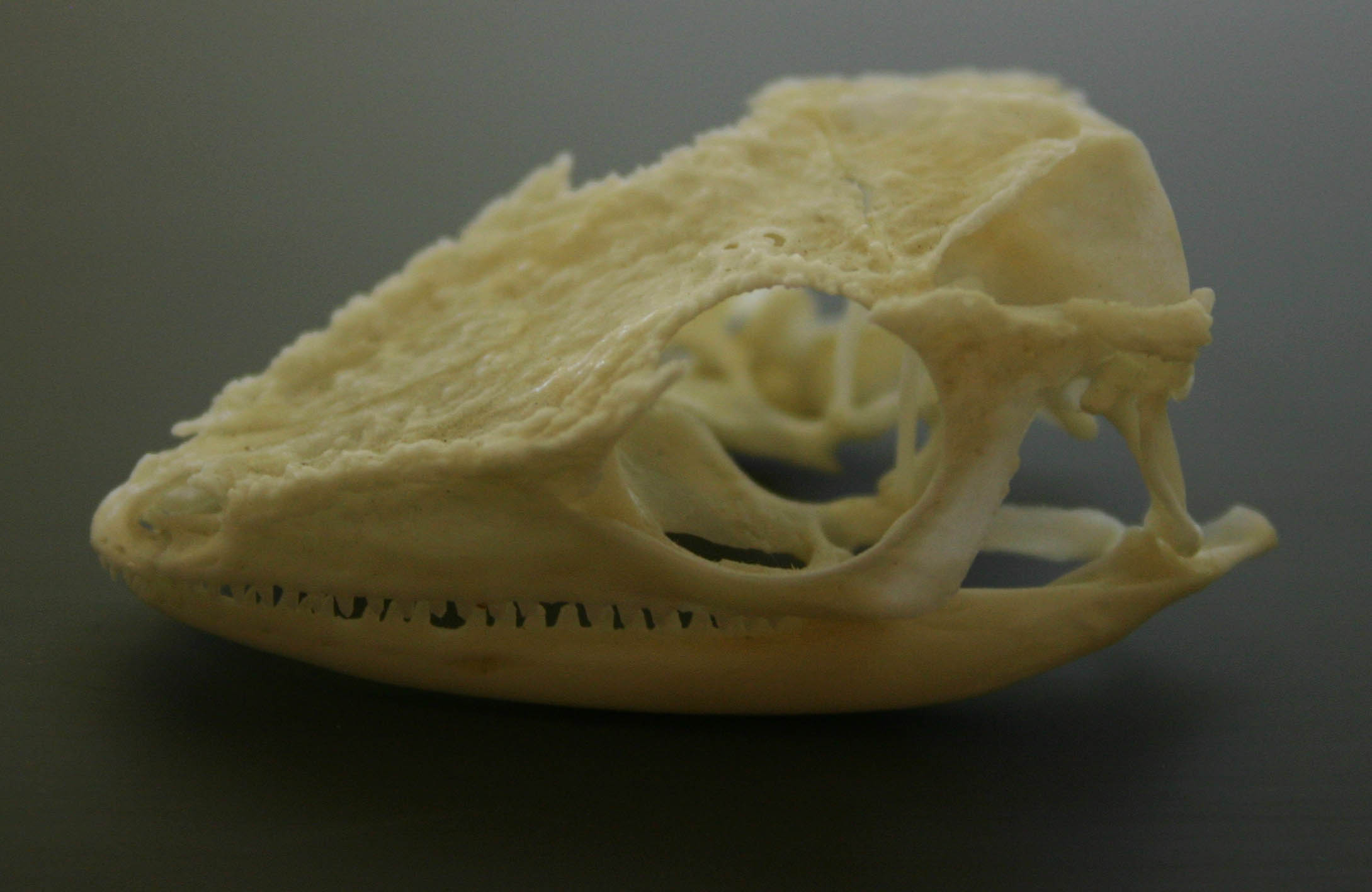

I once had a Cuban Anole (Anolis equestris) as a pet when I was in high school – I still have his skull. Yea I know, it is creepy to have your pet’s head on a shelf. But we are approaching Halloween and at this time of year, creepy is cool.

A photograph of the skull of my old Cuban Anole (Anolis equestris).

A photograph of the skull of my old Cuban Anole (Anolis equestris).

I was reminded of my old pet because of an article which recently appeared in the scientific journal Nature (Helmus et al. 2014). In this article, the authors show that island biogeography – where species disperse and diversify based on island size and isolation – has been overturned in the Caribbean by economic processes. In the Caribbean, anoles have dispersed far and wide as contaminants with cargo of one sort or another. Several species have colonised new islands as stow-aways with cargo, or as fugitives from the pet trade. The sharp increase in anole dispersal began around WWII, and increased significantly after the “cold war” thawed.

Brown Anole (Anolis sagrei) in Florida (photo by Marlene Gifford).

Brown Anole (Anolis sagrei) in Florida (photo by Marlene Gifford).

Cuba stands out (Figure 1) as a large island with diverse habitat that is not geographically isolated, but has not been invaded by hordes of rampaging anoles. The authors of this new paper suggest that the isolation of Cuba is economic, and there are few chances for stow-away lizards to get a toe-hold on that island. However, lizards were able to leave. Cuban Anoles have invaded islands on Great Bahama and Little Bahama banks, several locations on mainland Florida, and as far west as Oahu. The Brown Anole, also from Cuba, has invaded Belize, the Cayman Islands, southern Georgia, Texas, Alabama, Louisiana, California and Hawaii. Obviously these multiple exotic occurrences do not represent repeated independent dispersal events from Cuba, but they almost certainly represent translocation of anoles by commercial activity (the pet trade, gardening industry, or fruit shipments).

One of our Wall Lizards (Podarcis muralis) in Saanich.

One of our Wall Lizards (Podarcis muralis) in Saanich.

Compared to Cuba, our island is quite isolated as far as reptiles are concerned (and a touch cooler for much of the year). The water surrounding Vancouver Island is cold, tides are strong, and there is little chance that a lizard could raft over from the mainland. But like the Caribbean, the probability that exotic lizards move with human help is 1. Natural island biogeography is circumvented when animals are brought here intentionally, and released. Luckily most pet lizards escape or are released one at a time and never find mates. Within the Saanich area though, European Wall Lizards disperse in shipments of hay, in livestock trailers, and possibly also in plant pots (as eggs) or crates of produce. While our exotic lizard first arrived here intentionally, recent dispersal on Vancouver Island is increasing due to commerce. Perhaps the next bale of hay my wife buys for garden mulch, will explode with lizards when the twine is cut.

Who knows, if climate warms significantly, even anoles could colonise our island in the Pacific.

For more reading:

Lever, C. 2003. Naturalized reptiles and amphibians of the world. Oxford University Press, New York. 318p.

Matthew R. Helmus, M.R., D.L. Mahler & J.B. Losos. 2014. Island biogeography of the Anthropocene. Nature 513: 543–546.