On March 11, 2011, a magnitude-9 earthquake occurred off the coast of Japan, which triggered a monumental tsunami. The tsunami created massive destruction, taking lives, collapsing buildings, roads, railways and a dam and triggering a series of nuclear accidents. Tsunami debris continues to wash up on the shores of North America and Hawaii, seven years later. The Royal BC Museum has become the repository and permanent home for the biological material collected from this tsunami debris.

Fifty boxes of organisms collected from tsunami marine debris, both wet and dry, were shipped to the Royal BC Museum. This included some debris that was comprised of man-made objects (substrates), to which marine life was still attached. This sea life was primarily marine invertebrates such as barnacles, bivalves, bryozoans, and hydrozoans. The substrate materials included pieces of fibreglass, masonry, plastics, rubber, Styrofoam and wood, from objects such as docks, boats, buoys, household items and buildings. I agreed to carry out a conservation assessment of the dry material and to advise staff on the best way to store it.

The purpose of storing the Japanese tsunami debris collection at the Royal BC Museum is the long term preservation of the marine life. Research work will be carried out to identify any invasive species that have made their way here from Japan. The stability and the longevity of the substrates will influence the long term preservation of the attached sea life. If the substrates degrade, break apart and disintegrate, the attached colonies and individual specimens will be lost.

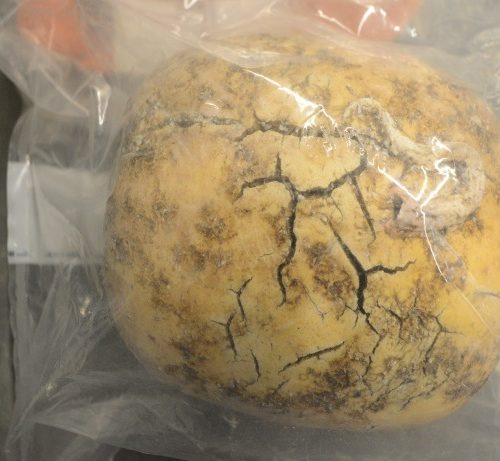

I assessed the collection and found that the dry, synthetic, substrate materials were deteriorated and dirty. All were discoloured, bleached, brittle and/or cracked. Some of the substrates were missing sections. There were no plans to remove residual sea salt and sand from the substrates, as this would damage the attached marine life.

I consulted with our senior conservator Kasey Lee, on the best storage conditions for plastics and rubber, as she had just returned from attending a Conservation of Plastics workshop at the Canadian Conservation Institute. The Conservation experts recommended that plastic materials be stored under freezing conditions.

I proposed to Dr. Henry Choong, our curator of Invertebrate Zoology and Heidi Gartner, our Collection Manager of Invertebrate Zoology, that the dry tsunami debris material be stored in a chest freezer, at minus 20◦ C. This would halt the deterioration processes of the plastics, and prevent the loss of marine life. It would also reduce the off-gassing of volatile acids from substrate materials such as wood and rubber. This would preclude the development of Byne’s disease, the chemical and physical breakdown of carbonate-based materials such as shells, due to exposure to acids.

I also suggested that, as a precaution, unbuffered acid-free tissue paper or card be added to the storage containers. This would serve as a humidity buffer because the deterioration processes of some plastics are accelerated in the presence of moisture. As rubber will continue to oxidize in freezing conditions, to slow down its deterioration rate, I also recommended that an oxygen scavenger be added to the sealed storage boxes containing the rubber substrates.

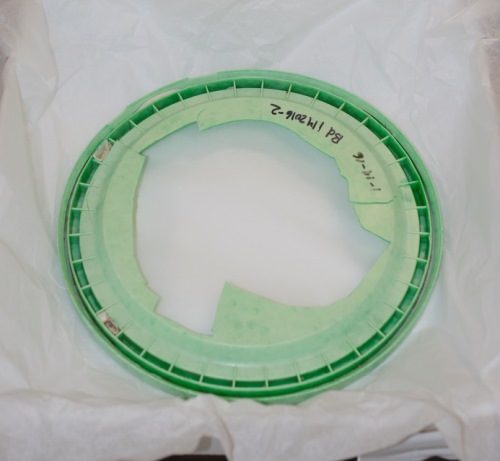

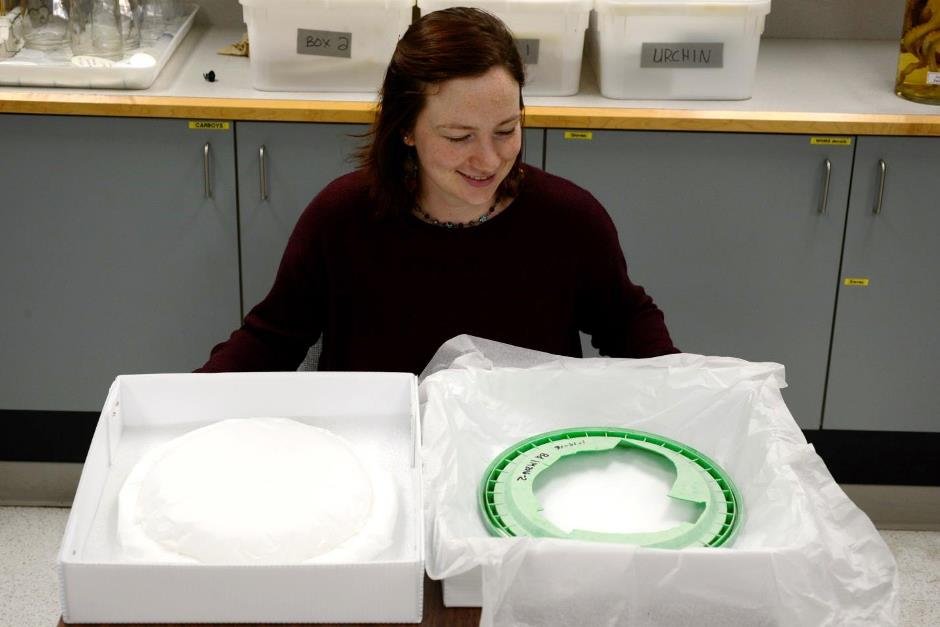

I provided advice to contractor Pascale Archibald on proper storage containers and supplied her with some of the conservation – approved storage materials to house the tsunami debris collection. She wrapped individual objects and cushioned them in unbuffered, acid-free tissue paper in clear polystyrene Durphy boxes. Pascale also made custom storage mounts for the irregular-shaped substrates, using corrugated polyethylene known as Coroplast and polyethylene foam called Ethafoam.

Re-housing of the dry tsunami debris material for long term storage is now completed. The substrates are supported without damaging the attached sea life. An oxygen scavenger will be added to the containers with the rubber substrates and all of the newly-housed dry material will be moved into a chest freezer in the Invertebrate lab.

The green plastic lid is now stored on a cushioned mount made of Ethafoam and polyester fiberfill in a custom-built Coroplast box.

Identification of several of the plastics will be carried out with FTIR analysis (Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy) at the Canadian Conservation Institute.

A temporary display of the Japanese tsunami debris collection can be viewed in the Royal BC Museum Pocket gallery in Cliff Carl Hall, until Sunday, October 14, 2018.