Collections, Knowledge and Engagement

- GR-3346.37 2021 Speech from the Throne

- The archives’ most recent record, created less than a year ago·

- GR-3518 Records of the Provincial Health Officer *

- This accrual covers the records of Dr. Perry Kendall, who served as the Provincial Health Officer from 1999 to 2018. The records address the health of Indigenous populations, water quality and pandemic influenza preparation among other public health topics.

- GR-3676 and GR-3677 Cabinet committee records and Premiers’ records*

- Large accruals were added to these series this year, documenting cabinet proceedings and priorities. Most records up to 1991 are publicly accessible.

- GR-3890 Drafting legislation case files*

- Comprehensive records covering all aspects of the process for drafting and approving provincial legislation. The records relate primarily to the 1970s and 1980s.

- GR-3948 Notebook related to the Tsilhqot’in War

- This delicate and difficult to decipher notebook relates to the events of the 1864 Tsilhqot’in War. It includes a diary of a group of settlers attempting to apprehend the Indigenous men allegedly involved in the deaths of several settlers.

- GR-3996 Conservation Officer Service major investigation case files*

- The series consists of the major investigation case files of the Conservation Officer Service between 1992 and 2007. Major cases are serious in nature and address complex issues such as trafficking animal parts, big-game poaching, illegal fishing or guiding, or selling animals for human consumption that are procured illegally.

- GR-3999 Environmental Appeal Board records*

- This series includes appeal files submitted to the Environmental Appeal Board and its predecessors: the Pollution Control Board and Pesticide Control Board. The records document the government’s management of the environment.

- GR-4000 Provincial Police circulars and wanted posters*

- This series includes a variety of informational posters for alleged criminals wanted across Canada and the United States. Many of the records are pasted into indexed volumes, serving as simple criminal record “databases.”

- GR-4002 Forest Practices Board meeting files*

- This series includes records of the Forest Practices Board which serves as the independent watchdog for sound forest and range practices in the province.

- GR-4005 Conservation Officer Service wildlife attack final reports*

- This series consists of final reports summarizing wildlife attacks on humans created by the Conservation Officer Service between 1991 and 2012. They illustrate the evolution of wildlife attack investigative technique, causes of wildlife attacks, and methods used to dispatch wildlife.

- GR-4008 BC Ambulance Service and air evacuation major accident and investigation files*

- This series consists of BC Ambulance Service (BCAS) and air evacuation major accident and incident investigation files between 1992 and 2011.

- GR-4041 Witness statements from CPR train robbery

- These records purport to be related to a train holdup by the infamous Bill Miner at Ducks. The details match other historical accounts of the incident; however, the year is wrong! These may benefit from some further research.

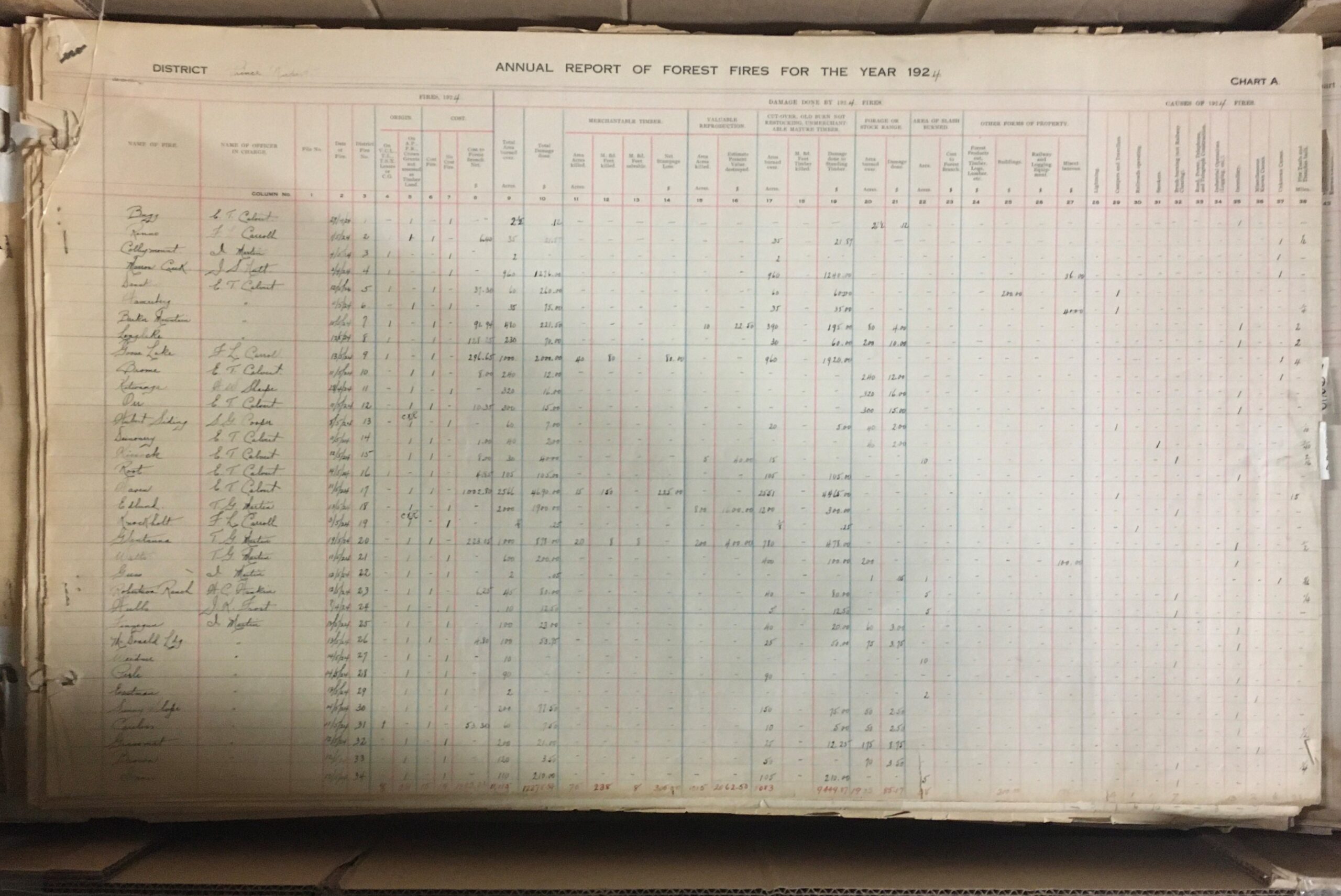

- GR-4048 Prince Rupert Forest District wild fire mapping records

- These huge volumes document wildfires in the Prince Rupert region from 1921 to 1980

- GR-4051 British Columbia Lottery Corporation’s ombudsperson’s investigations*

- This series consists of the ombudsperson’s investigation into the British Columbia Lottery Corporation’s prize payout procedures between 1999 and 2010. BCLC retailers and BCLC retailer employees appeared to be winning major prizes at a higher rate than other players in the province. The public and the media expressed concern that some of those winning tickets may actually belong to ordinary players.

- GR-4063 Cariboo government office records

- This series contains colonial records from the Cariboo region, including Barkerville. Records cover all aspects of government administration in the area from registering mining claims to court cases to crime statistics.

- GR-4064 Correspondence regarding immigration

- This series includes correspondence of the Provincial Immigration Officer from 1903-1905. Many records relate to the deportation of Japanese people under the racist 1904 Immigration Act.

- 24930E Plan of the No. 2 Extension coal mine

- This plan was made as part of the investigation into the cause of a 1909 explosion in the Ladysmith mine, resulting in the deaths of 32 men.

- GR-0522 Kamloops Government Agent land records

- This is a large series of records (160 boxes) that show a comprehensive history of land use in the Kamloops area over 100 years. This includes the time period the land was managed by the Canadian government as part of the Railway Belt.

- GR-3929 Riverview Hospital Historical Collection*

- This collection includes a wide variety of records related to the operation of Riverview Mental Hospital (previously known as Essondale). The records were collected and maintained by the Riverview Historical Society. With the closure of the hospital in 2012, government records in the society’s holdings were transferred back to the government and have recently been made available in the archives. The collection includes records of all media and provides an overview of the hospital’s history, grounds, staff, and patient care.

- 10am-12pm, Tuesday August 24th – teachers from SD61, 62, 63 or 79 (onsite at the museum)

- 10:30-12pm, Wednesday August 25th – teachers in districts beyond Greater Victoria region (online format)

- aSchool of Biology, Faculty of Biological Sciences, University of Leeds, Leeds, U.K.

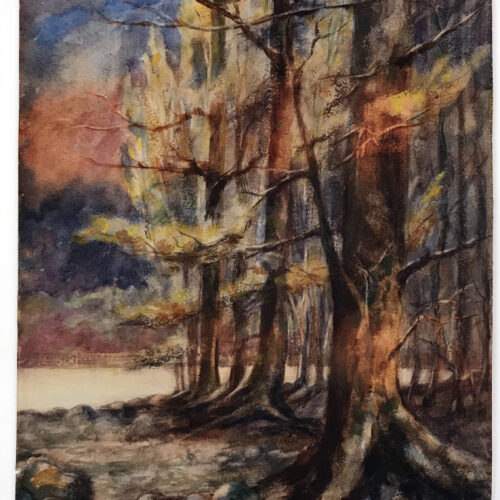

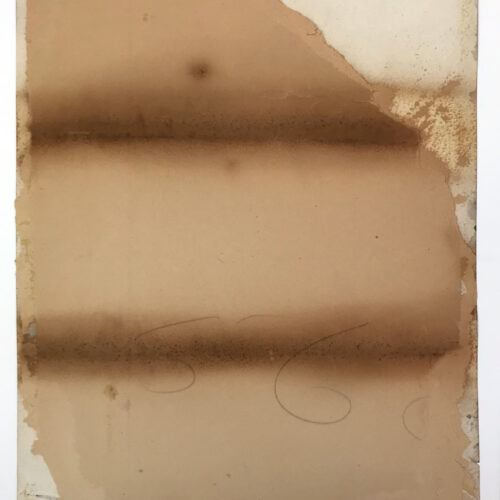

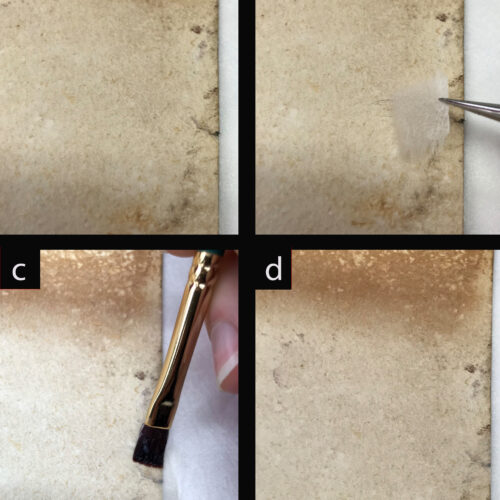

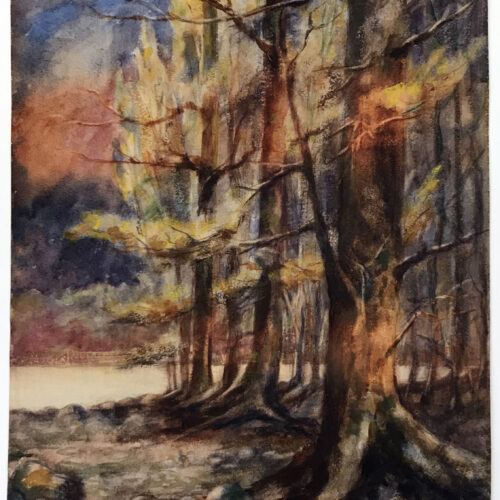

bRoyal British Columbia Museum, Victoria, BC, Canada - A partial backing means that the painting is not supported evenly, which often leads to folds, creases and other types of damage if the work is not handled very carefully

- Differential support can also lead to deformations in the paper because some areas of the sheet are constricted from movement (with environmental fluctuations) and some aren’t, leading to a build-up of internal stresses

- The poor-quality cardboard was also very brittle and likely to crack or snap. If a snap in the cardboard were to happen, this would inevitably translate into bends, creases or even breaks in the painting as well.

- Acidic components of the poor quality wood pulp cardboard (as well as acidic components that appear to have been absorbed from another source, visible as brown lines across the cardboard backing) will leach into the painting causing the paper to degrade and become brittle and discoloured. This could eventually affect the paint as well.

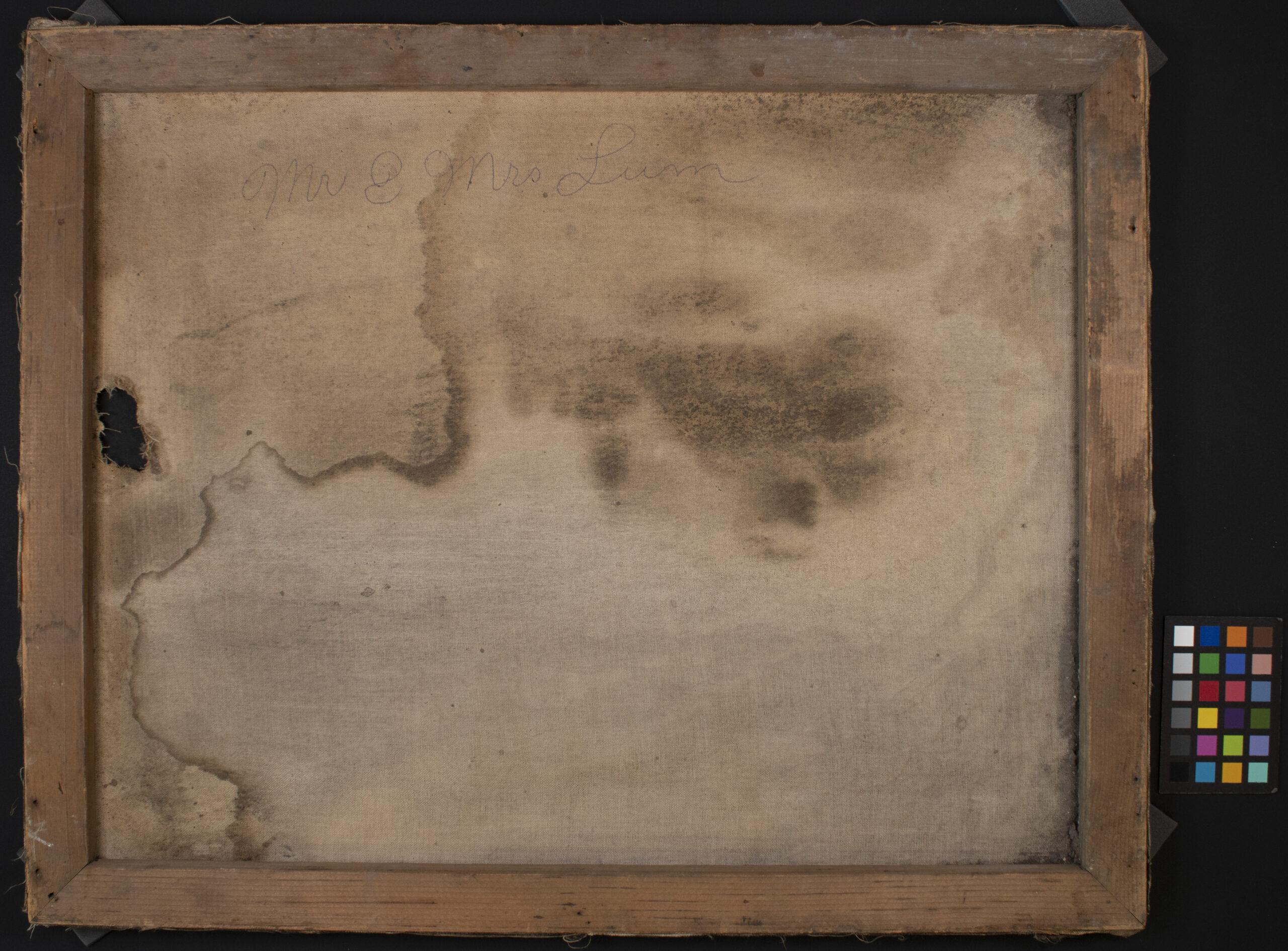

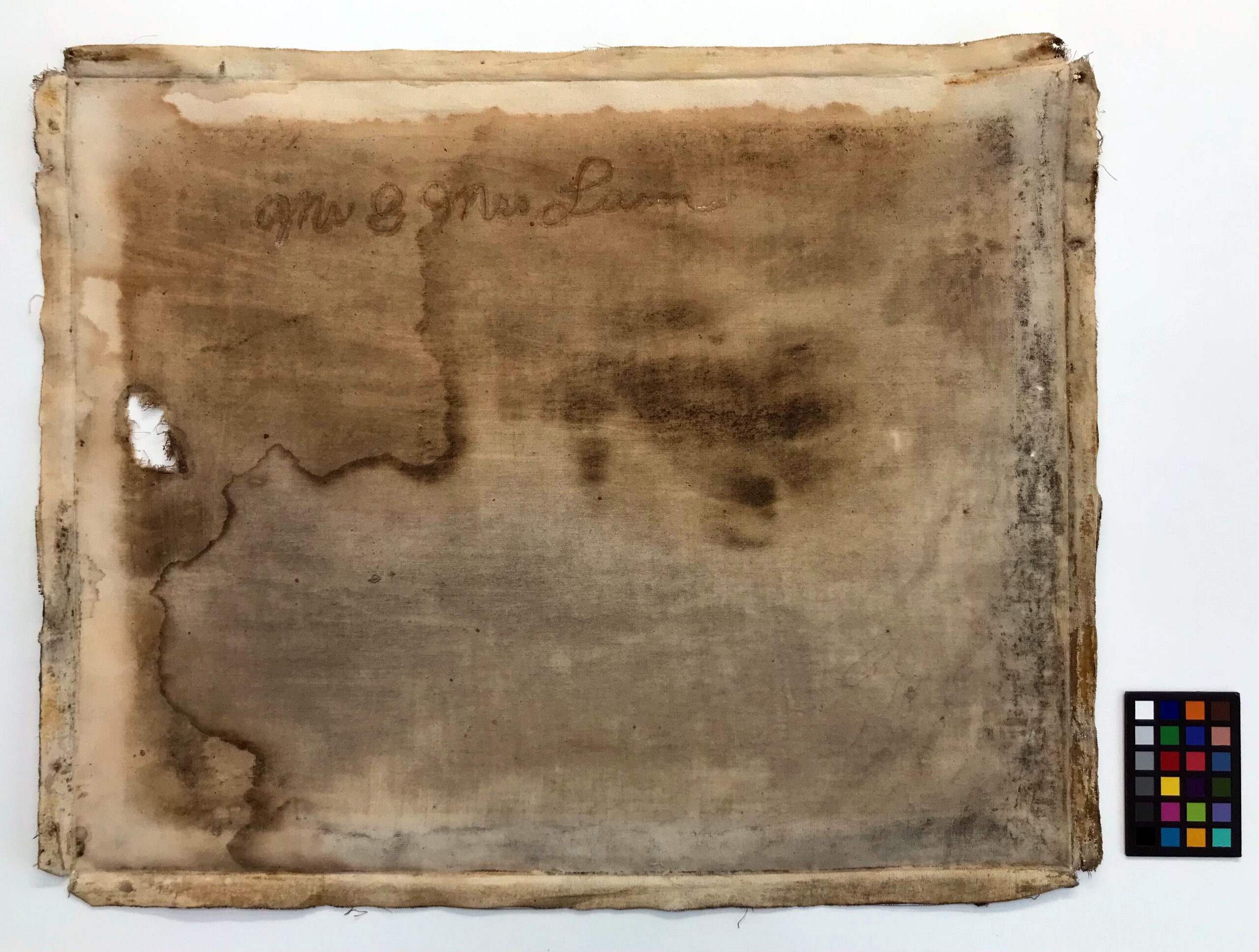

As the museum and archives prepare to move the collections to the new Collections and Research Building in Colwood, BC, more items are arriving in the Conservation labs for treatment to ensure they are stable enough to endure the journey. This past year, one portrait made its way to the paper conservation lab in need of pre-move stabilization. In this case, a large hole and obvious moisture damage were cause for concern.

This portrait of Mr. and Mrs. Lum (BC Archives, J-01350) is one in a collection of four (BC Archives, MS-3411). Mr. Chin Lum Kee, also known as Ah Lum, was born in Guangdong (previously known as Canton), China in 1835. He arrived in the new colony of British Columbia during the Fraser River Gold Rush. While in Sto:lo territory, he met his wife, Squeetlewood, also known as Lucy, who was born in 1854.

The portrait is a solar enlargement, based on a salted paper print (more information on this type of photography below). Black and white crayon have been used to work up the figures’ clothing and watercolour has been used to add soft colouring to the faces and background. In keeping with photographic portraiture of the time, the figures are captured from the chest upward with their bodies fading softly into the bottom of the picture plane. This solar enlargement on paper has been mounted to canvas and stretched over a wooden strainer.

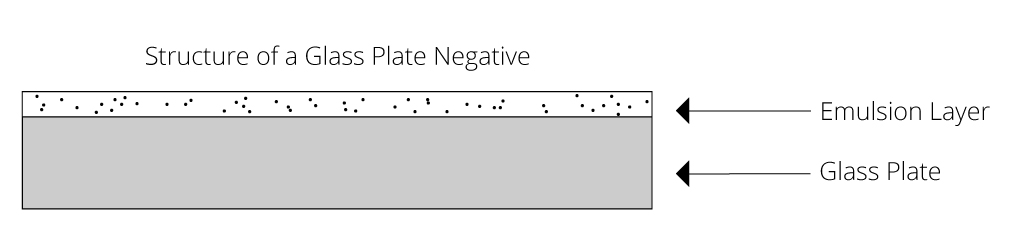

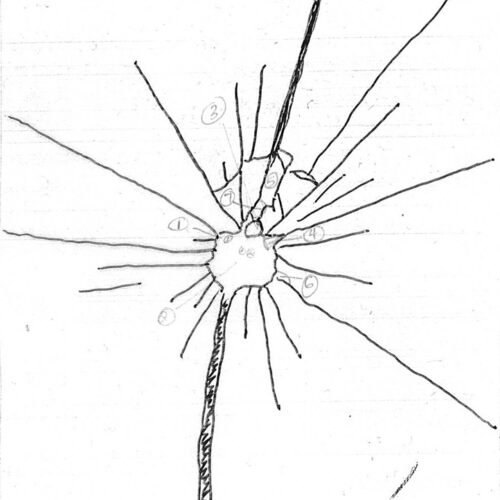

A Brief History of Solar Enlargements

Solar enlargements, also known as crayon portraits, were produced between the 1860s and the early 20th century. During the 19th century, photographic prints were made by placing photo-sensitised paper in direct contact with a photographic negative. Making a photographic print larger than the original negative began to be possible in the late 1850s with the invention of “solar cameras”. These enlarged prints required lengthy exposures and were faint and soft-focused. Furthermore, any imperfections in the photographic negative would be amplified in the enlargement.

As a result, these faint photographs were used as a sort of under-drawing upon which charcoal and coloured paints and crayons were used to retouch and enhance the image. It was common for artists to be employed alongside photographers for this purpose.

The most popular process for these enlarged photographic “under-drawings” was the salted paper print, however albumen prints could be used as well. Bromide enlarging paper was introduced in the 1880s which employed a gelatin emulsion layer available in many different surface textures. For more information on historical photographic processes, visit the Image Permanence Institute’s Graphic Atlas.

Condition Issues

The portrait of Mr. and Mrs. Lum came to the conservation lab because it was not in a condition where it could be safely handled. There was a large hole in both the paper photograph and the canvas behind it. The paper had been worn away along the left edge, resulting in a loss of some of the image. This is likely, at least in part, the result of some previous moisture damage. There were also tideline stains across the image from previous moisture damage. The adhesive holding the paper photograph to the canvas was disintegrating (or previously dissolved?) which meant most of the photograph was not actually attached to the stretched canvas support and was therefore more vulnerable to creases, rips and tears. Finally, the whole structure was heavily soiled with dirt, dust and debris.

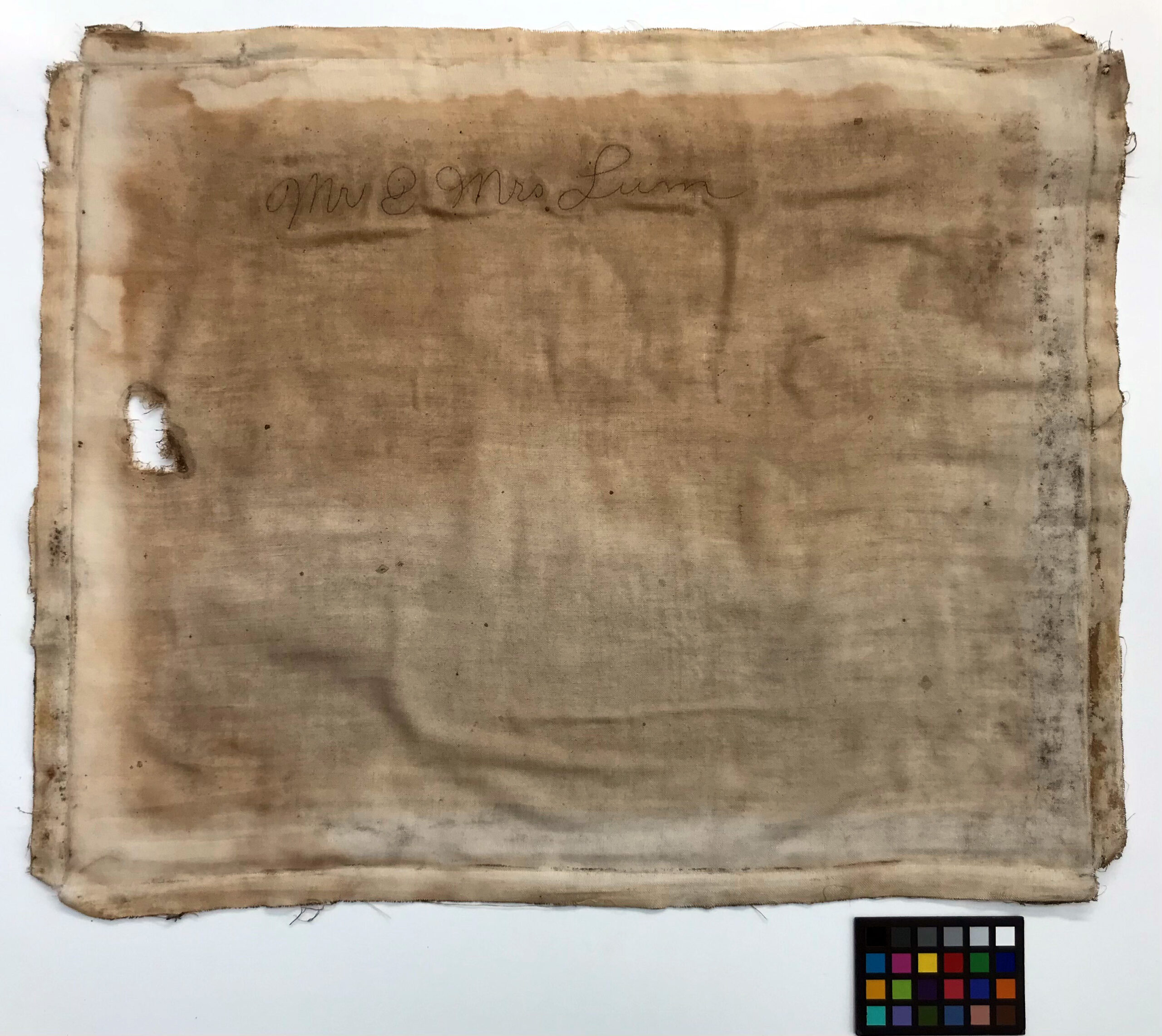

Figure 3. Bottom edge of [Mr. & Mrs. Lum], before treatment. Photograph lifted to show underside of primary support (paper) and the secondary support (canvas).

Treatment

Treating a composite object is always difficult. Since this portrait was so heavily soiled and already stained by moisture damage, an aqueous wash (water bath) was deemed necessary. The decision was made to disassemble the object, which meant removing the partially attached photograph (or “primary support”) from the stretched canvas and then removing the canvas from the strainer. Each piece was then cleaned separately and reassembled once dry.

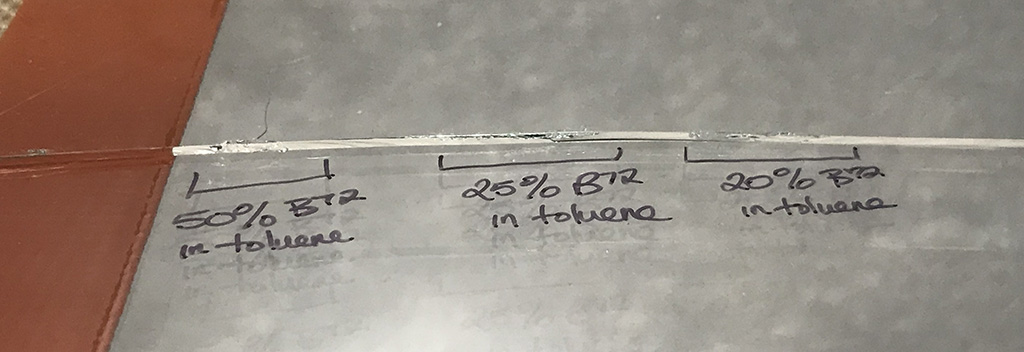

Cleaning the Primary Support

To be sure none of the media would be affected by washing, solubility testing of all the different media types as well as the staining was carried out under the microscope. The media was already thought to be quite stable—after all, it had survived moisture damage in the past—and the solubility tests proved this to be the case. The tidelines had mixed results with some appearing quite soluble and others less so. These results were enough to suggest that the primary support would benefit from a wash: the media would not be affected and the stains would likely disappear or at the very least, be reduced. Washing out these stains and other products created as a result of deterioration in the paper would also raise the pH, making the paper more chemically stable.

Figure 4. Recto of [Mr. & Mrs. Lum], before treatment. Paper triangles point to areas where solubility testing was carried out under the microscope.

Then, the solar enlargement was washed in an aqueous bath. There were some small fragments that had come detached from the left side of the photograph. These fragments were also washed but using a different, more delicate method. These fragments were gently placed on wet Tekwipe®, a non-woven fabric made from cellulose and polyester. This fabric has capillaries that draw clean water from one basin through the fabric, wetting out the paper resting on its surface and removing dirt and other products of deterioration in the paper and then move the dirty water along the rest of the fabric to the empty basin on the other side.

Figure 6. Primary support being removed from aqueous bath. Note the colour of the wash water has turned yellow with dirt and the water-soluble products that are formed as paper deteriorates.

Figure 7. Small fragments from the left side of the primary support being washed on Tekwipe® using capillary action.

Once washed, all pieces for the primary support were placed under weight to dry flat. After a few days of drying, the photograph was humidified and a thin piece of Japanese tissue paper was applied to the back. This lining provides a consistent support layer and prevents any further losses or tears around the areas that have already suffered losses.

Figure 8. Recto of solar enlargement after aqueous wash and lining with Japanese tissue. Note that some tidelines remain but they are reduced. The staining across Mrs. Lum’s face has been washed away.

Cleaning the Canvas

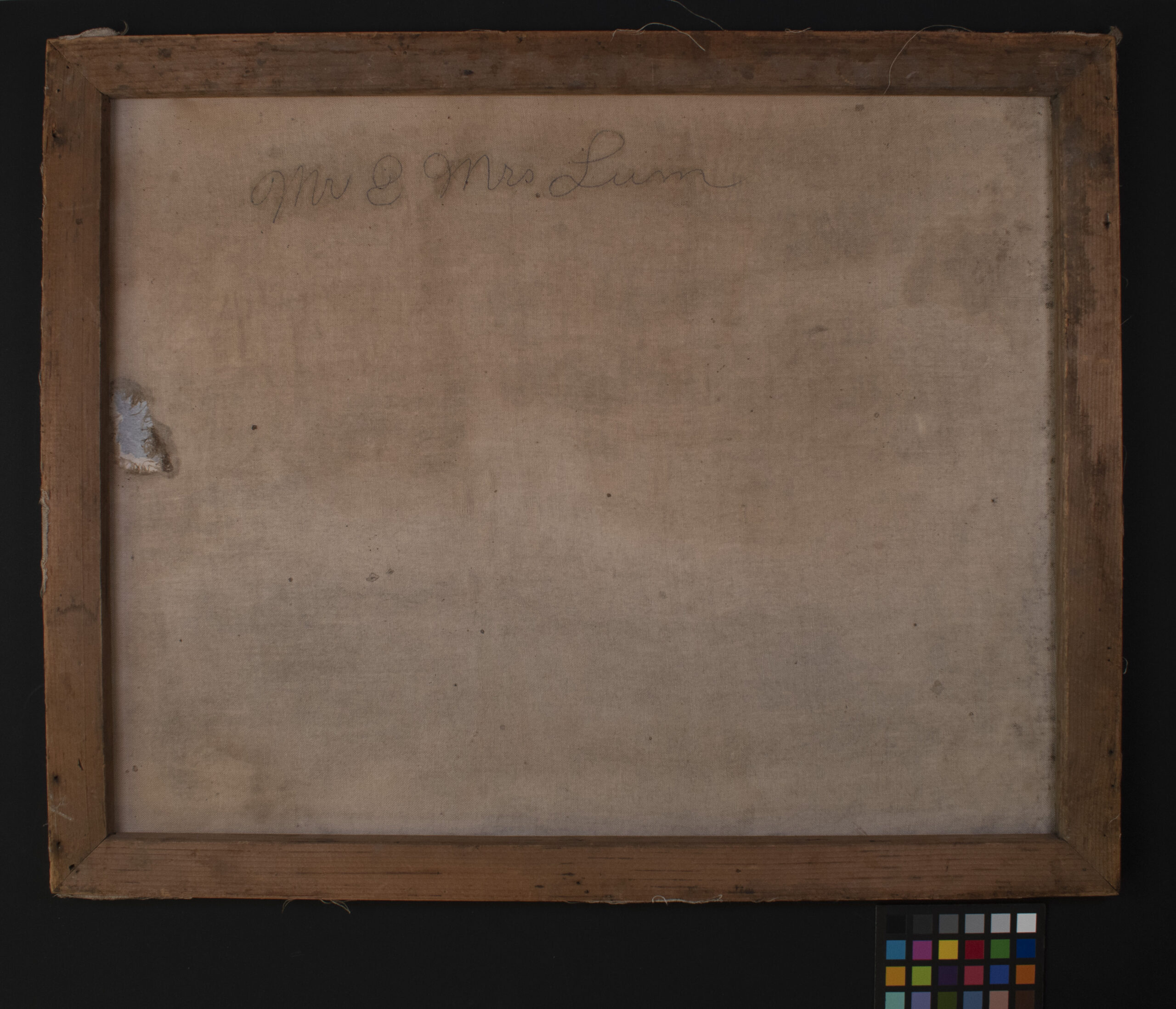

The canvas was gently removed from the wooden strainer and vacuumed on very low suction to remove loose clumps of dust and dirt that were deposited on the surface, particularly along the perimeter where the strainer had been.

The canvas was also heavily soiled and need a wash, however there is an inscription in blue ink on the back of the canvas that was discovered to be water-soluble during the solubility testing mentioned previously. To protect that ink from being solubilized during the wash, cyclododecane was applied as a temporary seal. Cyclododecane is a waxy substance that becomes liquid when warmed. It was applied over the ink as a warm liquid and solidified in place upon returning to room temperature. One of the unique properties of this wax is that it sublimes (passes directly from a solid state to a gas state) at room temperature over relatively short periods of time.

With the ink inscription temporarily sealed with cyclododecane, the canvas was washed with the help of textiles conservator Colleen Wilson. After the wash, it was allowed to dry and the cyclododecane was allowed to sublime, leaving the ink behind, unaltered.

Figure 9. Paper conservator, Lauren Buttle, applying cyclododecane to canvas to temporarily seal the water-soluble inscription in preparation for an aqueous wash.

Figure 10. Verso of canvas after being removed from strainer, with cyclododecane applied to inscription, before aqueous wash.

Figure 11. Textiles conservator, Colleen Wilson, blotting canvas with a sponge during first bath with detergents.

Figure 12. Verso of canvas 1.5 weeks after aqueous wash and after cyclododecane has fully disappeared.

Cleaning the Strainer

The wooden strainer was also vacuumed to remove surface dirt and dust. Some residual adhesive left on the outside edges of the strainer were re-moistened and removed with a Teflon spatula.

Reassembly

With all the individual pieces cleaned, the lined photograph was reattached to the canvas and then the canvas was re-stretched and adhered to the outside edges of the strainer. The Japanese tissue lining of the primary support provides support over areas of loss.

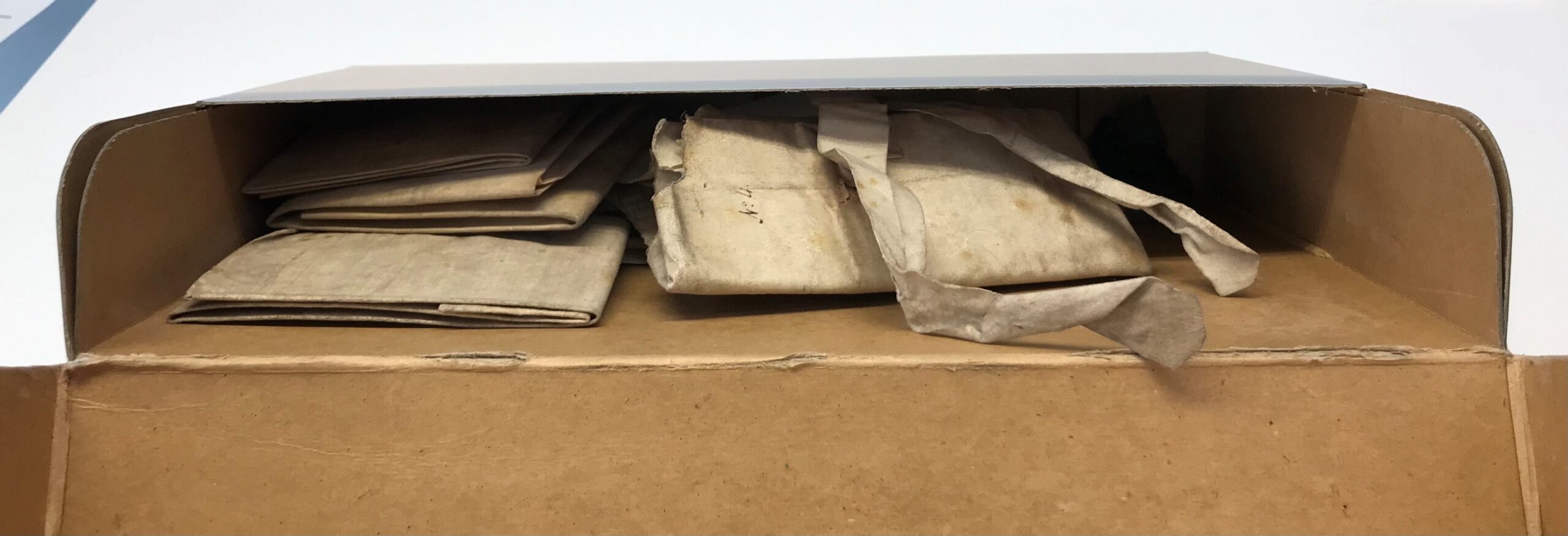

Re-Housing the Lum Portraits

While the main reason for diverting the Lum portraits to the conservation lab was to stabilize them for the move, there was also the issue of how to safely transport them. When they arrived in the lab, they were altogether in a paper folder, a housing system that was not offering sufficient protection in the context of a collection move.

Once conserved, this portrait, as well as the other three portraits in the collection, were placed in HTS (handling-travel-storage) frames. These storage structures are based on models developed by the Canadian Conservation Institute and the National Gallery of Canada. These frames will provide protection to each work and can be easily re-used for other similarly-sized works if necessary.

References

Canadian Conservation Institute (2018). “Framing a Painting – CCI Note 10/8”. Government of Canada. Framing a Painting – Canadian Conservation Institute (CCI) Notes 10/8 – Canada.ca

Reilly, James M. (1986). Care and Identification of 19th-Century Photographic Prints. Rochester, NY: Eastman Kodak Co.

Whitman, Katharine (2005). “The Technology of Solar Enlargements”, Topics in Photographic Preservation, Vol. 11, pages 104-110. Washington DC: American Institute for Conservation of Historic & Artistic Works. History (culturalheritage.org)

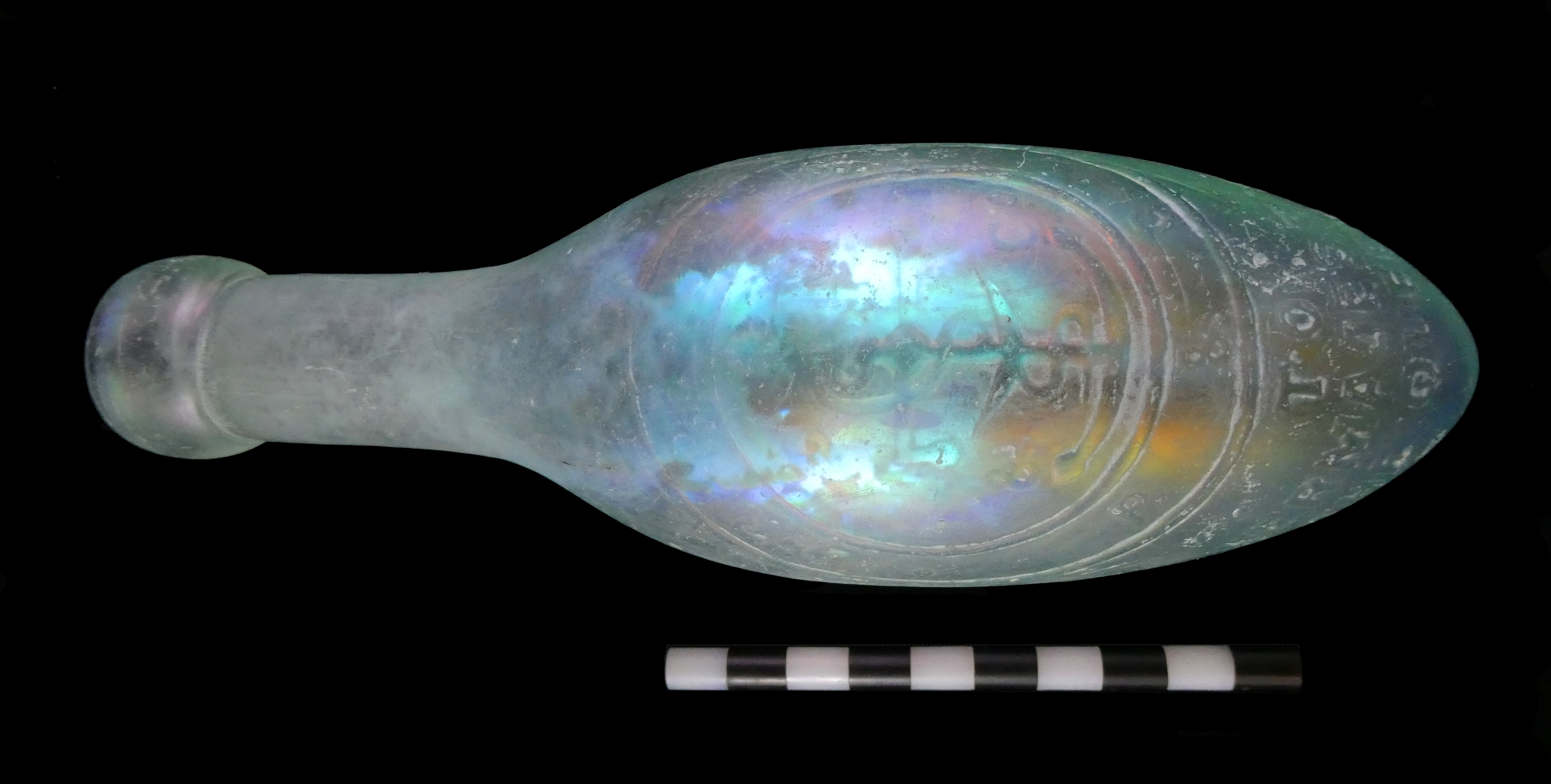

A few months ago, a box of archival records that had been requested for access was transferred to the Royal BC Museum paper conservation lab. These documents were part of the Archibald Menzies fonds, a small collection of records and belongings related to Archibald Menzies (1754–1842), a Scottish surgeon and naturalist who accompanied Captain George Vancouver aboard the HMS Discovery in 1791–95.

The documents in this box were mostly parchment and had been folded several times in the past, then piled into a box for storage. Upon retrieving the box, the archivist realised that none of these documents were easy to open. The parchment was hard and inflexible, suggesting that any attempt to forcibly flatten out the records might lead to damage. When problems like this arise, these materials are diverted to our conservation team for assessment and remedy.

So, how can we convince parchment to relax, open up and share its hidden secrets? First, we need to understand where it’s coming from.

The Nature of Parchment

Parchment is made from animal skin—usually that of a calf, sheep or goat. The skins are removed from the animal, dehaired and defleshed, and then treated with a lime or other alkali solution. After liming, the skin is dried under tension, and in some cases, surface treatments are carried out to make it more suitable to receive inks and paints. Before the invention of paper, parchment was a common writing support in Europe and parts of the Middle East. It continued to be used as such for several centuries after papermaking became popular and widespread.

Parchment is very sensitive to moisture and heat. This means that when water is present, the parchment will expand and absorb moisture. When conditions become warm and dry, the parchment will shrink and release moisture. Over long stretches of time, these cycles of shrinking and expanding cause the parchment to deteriorate, becoming distorted and hard.

Relax and Unfold

The parchment documents in this collection were tightly folded, and attempts to open them were met with strong resistance. Forcing them open could have potentially led to cracks, breaks and losses in the document; however, leaving them as they were meant that no one could read them.

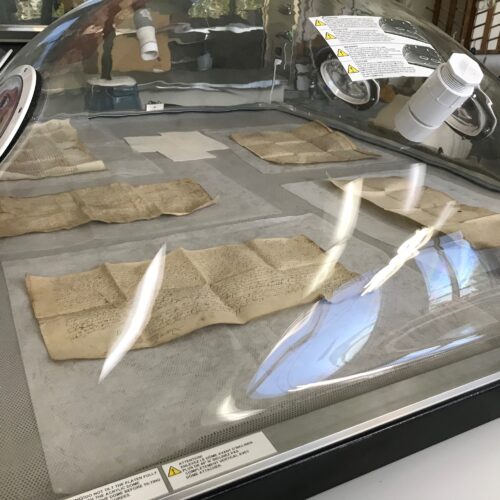

To open these documents without incurring damage and loss, we needed them to relax. This state of inner peace was achieved with the careful introduction of moisture. Since parchment is so sensitive to moisture, the use of moisture to treat deteriorated parchment might seem counterintuitive; however, in the case of this treatment, moisture is delivered in the form of water vapour (never liquid water), and it was delivered with control.

The tightly folded documents were placed in an environmental chamber where the relative humidity (RH) could be raised using an ultrasonic humidifier. The RH levels were monitored throughout this treatment using a hygrometer placed in the chamber. Slowly, over a period of approximately two hours, the documents were unfolded bit by bit, until they were relaxed enough to fall completely open.

Once the documents had fully revealed themselves, they were placed under very gentle pressure between felt pads to ensure they dried flat.

A New Home

Now that these documents are open for viewing, they will be stored flat. They have been transferred to a flat storage box with custom padded trays for two of the documents, with seals and cords attached, ready for the next researcher.

Every year the Government Records team at the BC Archives processes over 2,000 boxes of records created by the provincial government. Most of these records can now be accessed by anyone, even you! Just remember that all government records are covered by privacy legislation, such as the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act. This means some records have access restrictions on sensitive or personal information. Here is an overview of just a few of the record series from the last year or so that are now available in our database.

A page from the GR-4064 fire atlas. Each volume measures over three feet by four feet and weighed over 60 pounds.

A page from the GR-4064 fire atlas. Each volume measures over three feet by four feet and weighed over 60 pounds.

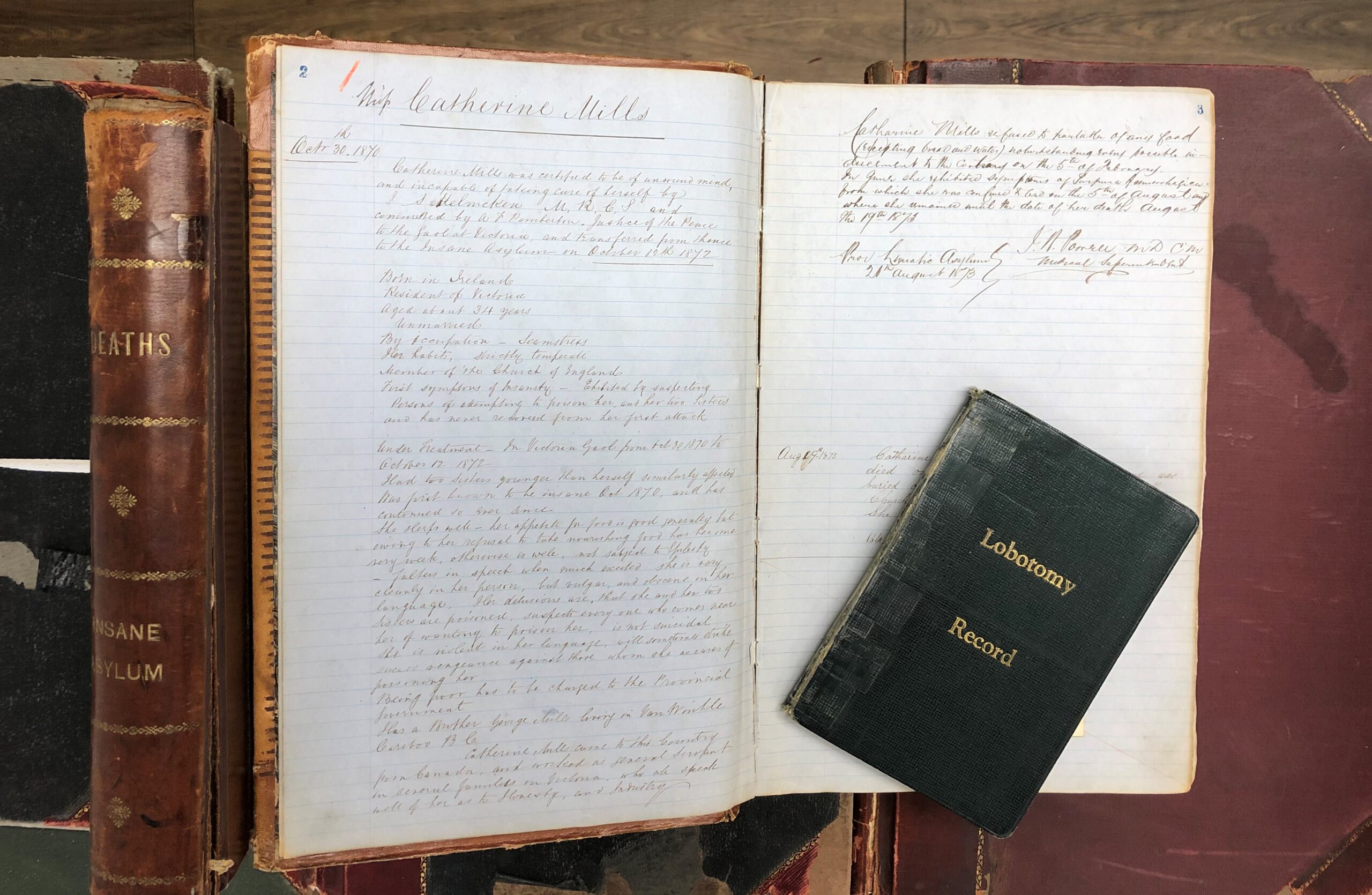

A selection of volumes from GR-3929, including the first patient file from 1870.

A selection of volumes from GR-3929, including the first patient file from 1870.

Bonus records! Here are some other records that were made available a bit before 2021, but are still worthy of a mention:

*These series include sensitive personal information or other restricted records that are not publicly accessible.

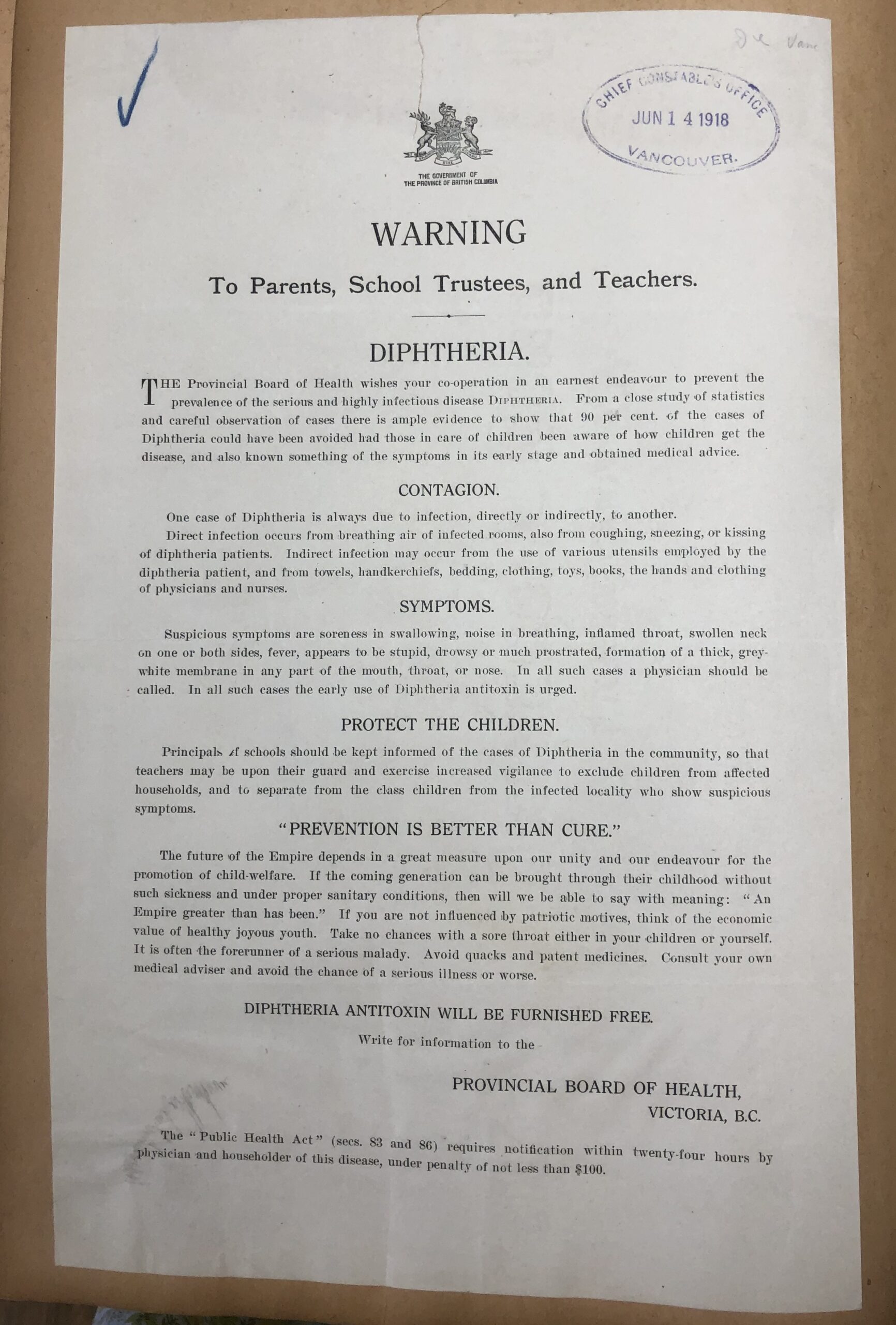

A public notice to be posted in schools, included with police records in GR-4000

A public notice to be posted in schools, included with police records in GR-4000

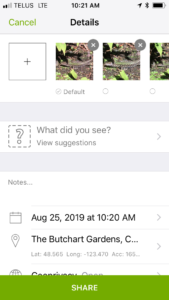

Lizard Lovin post

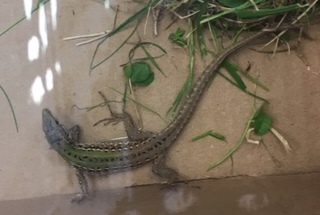

‘Tis the season: northern alligator lizards are busy making little lizards.

Have you seen alligator lizards mating? If so, please take note how long they spend together. Males bite the head and neck of females and hang on, sometimes for over 24 hours. Mating itself doesn’t take 24 hours—so perhaps males hang on to make sure other males are excluded.

In BC, the alligator lizards tend to vanish when new urban developments spread across the landscape—maybe (probably) the habitat is unsuitable, roadkill happens, a certain invasive lizard certainly doesn’t help, and well-fed domestic cats also take their toll, as do lawn mowers and weedwackers.

But if you are lucky enough to have northern alligator lizards in your garden, please take detailed notes on their activity, prey, and how they use your garden structures. It’s also helpful to record mating activity and how long a pair stays together. Community science (sometimes called citizen science) is a way to get very detailed views of species distributions to see how species are responding to our increasing sprawl.

Greg Pauly, curator of herpetology at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, studies natural history, evolution and conservation of reptiles and amphibians, and the impact of urbanization on biodiversity.

You can share photos and information with Greg at gpauly@nhm.org.

Here are a few of his blog posts:

Love in the Time of Coronavirus: The Alligator Lizard Version

Look Out for Amorous Alligator Lizards

Studying Lizard Love Through Citizen Science

Alligator Lizards: Mating season has begun – YouTube

Government is constantly evolving to meet the needs of the citizens it serves. This often results in the renaming and reorganizing of its various branches and departments. These changes can make it tricky to track which government body was responsible for creating and maintaining particular records through the years. To help myself better understand who created some of the land records I was working with, I set out to create a visual representation of how the land management functions of government moved around over time. This soon expanded to include several other ministries whose records I worked on. It eventually grew to cover all ministries (and their precursor departments) from 1871, when the province was created, to 2021.

Please see BC Government Ministry History Diagram for the most current version of the diagram.

I created the chart using information from BC Archives authority records, Orders-in-Council and lists of Cabinet Appointments from the Legislative Library. Ministries are shown in square bubbles and are connected to each other with arrows. The oldest departments are at the top, moving down to the current ministries at the bottom of the page. The ministries are arranged in columns that represent broad categories of government functions, such as health or agriculture.

Arrows with solid lines show that a ministry was renamed. This usually means it continued to do pretty much the same work and fulfill the same functions of its predecessor.

Arrows with dotted lines show that some functions moved to another ministry. Dotted lines also show links from ministries that are established (created) and disestablished. I was only able to note large changes; sometimes the various branches that make up a ministry were split between a half dozen other ministries, making it pretty impossible to track all their movements individually.

The complexity and change over time make this a bit overwhelming to look at all together. But the changing names of a ministry can provide a high-level snapshot of general trends in government’s priorities over time. Each ministry is usually focused on a single function or issue, such as providing health care or managing public forests. The evolution of ministries reflects what government thought was important—and what mattered to voters. To a certain extent, this also reflects what mattered to society at large, though government was dominated by white men for most of the province’s existence, and universal enfranchisement did not occur until 1952.

Government departments changed very little from the province’s creation in 1871 until the 1970s. Government was small. Initially, the Attorney-General and Provincial Secretary were responsible for functions that would be divided among a dozen different ministers today. The major changes involved the creation of new departments as the role of government began to expand in the twentieth century.

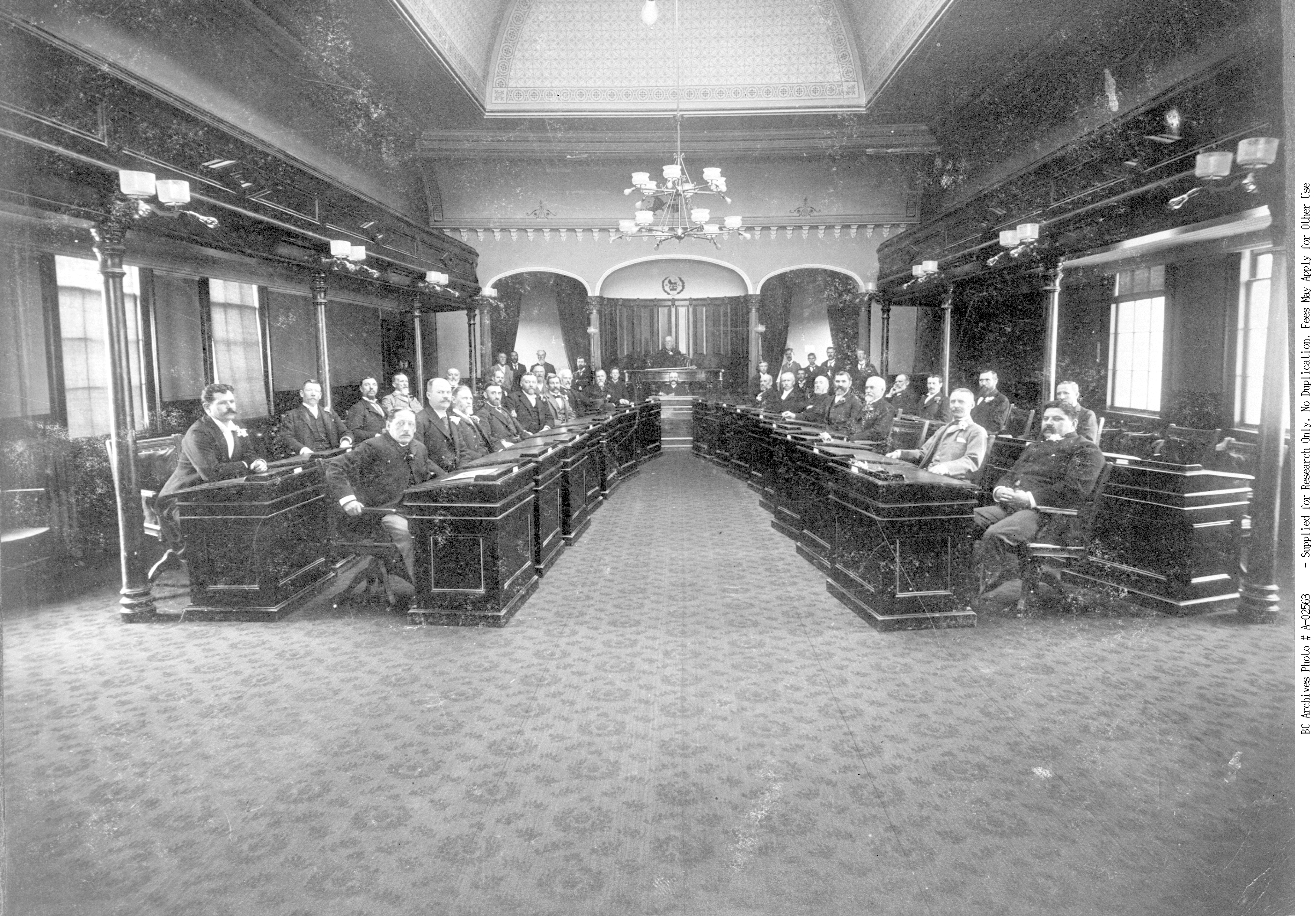

Members of the Legislative Assembly demonstrating some pretty good social distancing. Photo taken in 1870 in front of the Victoria government buildings known as the Birdcages, after the union of the two colonies and just prior to Confederation. C-06178.

Initially, building infrastructure and promoting the industrial harvest of natural resources (to expand economic opportunities for other white settlers) appears to be more of a priority than providing social supports. For example, two separate departments for railways and public works were established almost 50 years before the Department of Health Services and Department of Social Welfare were finally created in 1959.

In 1976, all departments were renamed and became ministries. After this point, changes became much more common. By the 1990s it seems to have become fairly standard practice for a newly elected government to reorganize Cabinet, appointing new ministers to differentiate themselves from the previous government and reflect changing priorities throughout their term in office.

Some ministries have remained remarkably similar over the last hundred years. Others have been regularly broken up, combined and moved around in ways that, at times, can seem confusing and a bit counterintuitive. For example, in 1978, the Ministry of Recreation and Conservation was disestablished and broken into several ministries, including a new Ministry of Deregulation.

BC Legislative Assembly, Seventh Parliament, Third Session, in 1897 in the Birdcages. Construction of the current Legislative Assembly building was completed the following year. A-02563.

Names have power. Word choice can really impact how people perceive things, and the level of importance or value they place on an issue. The arm of government responsible for social services provides a good example of this. It has fulfilled fairly similar functions over time, but the language around the work has evolved alongside societal beliefs about poverty. It began in 1959 as the Department of Social Welfare. Later names included the Department of Rehabilitation and Social Improvement, the Ministry of Human Resources and the Ministry of Employment and Income Assistance. Currently, it is the Ministry of Social Development and Poverty Reduction.

Establishing (or disestablishing) a ministry shows that government is assigning its affairs a certain level of importance, with an elected official appointed to focus on the function or issue. The creation of a Ministry of Women’s Equality in 1991, when BC’s first female premier Rita Johnson was in power, shows women’s equality was an important issue for government at the time. In 2001, this ministry was disestablished and lumped into the Ministry of Community, Aboriginal and Women’s Services with four other disestablished ministries, including the also-disestablished Ministry of Aboriginal Affairs.

Overall, I have found the chart a helpful way to track government’s changing responsibilities at a glance. My hope is that it can be a useful tool for researching archival government records. A record’s creator (often the ministry or department that created it) is one of the main things archivists look at when arranging and determining different series of government records (GR-numbers) in the BC Archives database. If you can think about the ministry that may have created the records you are looking for, it may provide access to some unexpected results. You can search for archival records by creator here.

Happy researching!

Help shape teaching resources for your provincial museum.

The Royal BC Museum is looking for BC French teachers to participate in one of two focus groups in August. We are looking for teachers from across the K-12 spectrum to participate, (eight teachers in each focus group, ideally with a spread across grade ranges).

We want your input on the kinds of resources you’d like to have available from the museum. What would support you in the classroom, online or on field trips? You’ll be asked to assess what we have currently available, and then identify high priority gaps where you’d like to see resource development.

Compensation

Participants will be paid $100.

Focus Group Dates

Results from the focus groups will inform a secondary phase which will contract a French educator to develop the identified resources and make them available on the Royal BC Museum Learning Portal and ShareEdBC websites

Contact Liz Crocker lcrocker@royalbcmuseum.bc.ca to sign up.

As a government records archivist, I process a lot of records related to land or resource use, and specifically forestry records. Since the beginning of British Columbia’s colonization, forestry has been a major part of the province’s economy. After over 150 years of industrial logging, the majority of the province has been disturbed by some kind of industrial activity, leaving an estimated 2.7% as productive old growth forest today.

Most land in the province is Crown land controlled by the provincial government. Crown land and resources—in this case timber—are leased or licensed to forestry companies to use. These agreements are generally referred to as timber tenures and can include a variety of uses, lengths of time they are valid for and other required management practices.

Managing all these resources has created a huge amount of government records. Many of these are now kept by the BC Archives for government reference and historical knowledge, and so that the public can hold its government accountable. I recently processed a series of records related to forestry in the Clayoquot Sound area, now part of GR-3659.

GR-3659 documents a type of timber tenure referred to as a Tree Farm Licence (TFL). Most of western Vancouver Island is covered by a handful of TFLs. TFLs provide a forestry company with almost exclusive rights to harvest timber and manage forest in a certain area for 25 years. Every 5 years, companies are required to create detailed plans outlining how they will manage the land and resources within the TFL area.

Working with the records in GR-3659 got me thinking about a related historical event—the 1993 Clayoquot Sound protests, also known as the War in the Woods, which occurred primarily on TFL 54 and TFL 57. So, I took a look at some of the other records that document it.

Protests and blockades began in the 1980s after logging was proposed on Meares Island in Clayoquot Sound. Several attempts were made by the government to reach a consensus between the members of the forest industry, environmentalists, municipalities and Indigenous Peoples. These included the Clayoquot Sound Development Task Force (GR-3535, box 921203-0023) and the Clayoquot Sound Development Steering Committee. Environmentalists left the Steering Committee in 1991 after the government refused to defer logging until an agreement was made. The Steering Committee ultimately dissolved in October 1992, without completing a finalized development strategy.

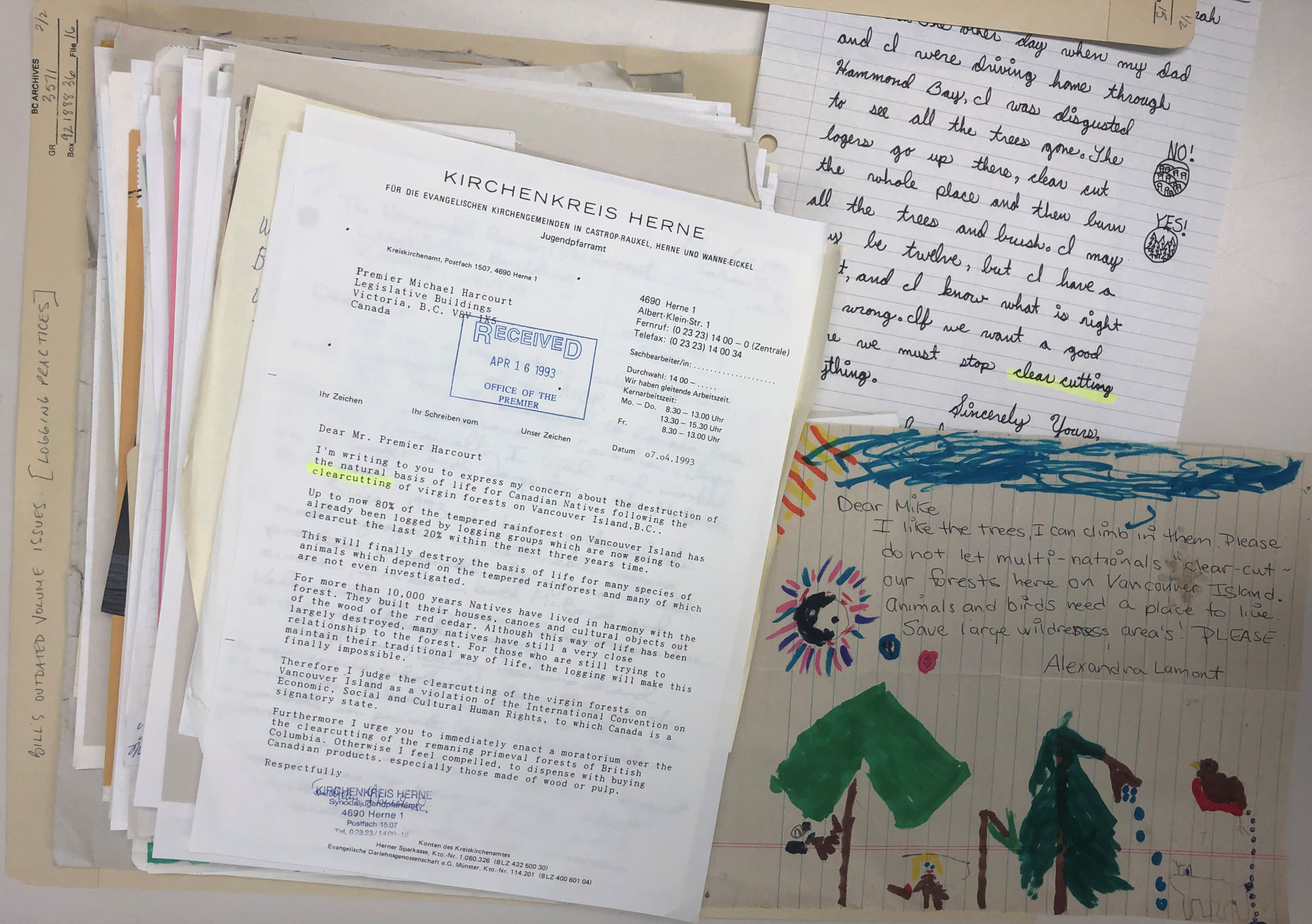

A few months later, in April 1993, Cabinet passed the Clayoquot Sound Land Use Plan, but it was widely contested. The government’s lack of consultation with local First Nations and the large area of old growth forest available for clear cutting resulted in protests that spread around the world. Protest camps and blockades were set up to prevent logging, in defiance of court injunctions. Police attempts to enforce the injunction led to over 800 arrests. Thousands of people protested over the summer of 1993, making it possibly the largest event of civil disobedience in Canadian history.

Ultimately, the government was able to reach a consensus with the Nuu-chah-nulth First Nation, whose traditional territory includes Clayoquot Sound, and new land use plans were developed. This also led to the creation of Iisaak, a new First Nations owned logging company operating in the area (some of their records are in GR-3659), and the designation of Clayoquot Sound as a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve.

Letters protesting old growth logging received by the Premier in 1993 from across Canada and the rest of the world (BC Archives, GR-3571, box 921888-0036, file 16)

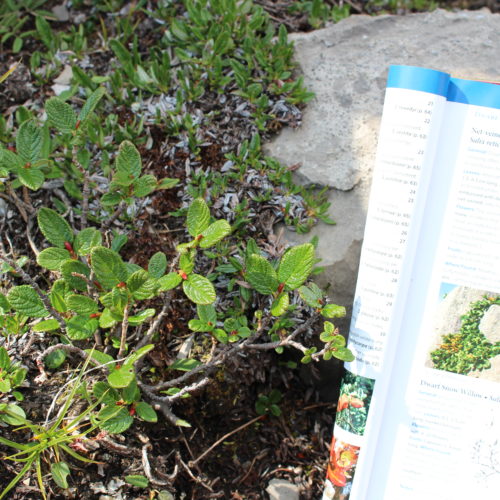

A small portion of the RBCM Native Plant Garden.

The native plant garden at the Royal BC Museum, with more than 300 species of plants, is a haven for wildlife in an otherwise heavily urbanized setting. The garden was initiated in 1968 in part to promote landscaping with our diverse native flora. The diversity of bird species that are known to visit the garden is truly impressive considering the downtown setting, and the garden also harbours a wealth of invertebrate animals: butterflies, bees, dragonflies, and damselflies, as well as many others.

Some of the animals are just passing through on their migration – for instance the eye-catching Green Darner dragonflies that have been seen there in the fall on their way south (yes! -some dragonflies migrate!) and the gorgeous Wilson’s Warblers that pass through on their way north each spring. Others are year-round residents in the garden: Song Sparrows, Spotted Towhees, while others come to the garden in the winter months and then head off to points north as the rest of the province warms up: Golden-crowned Sparrow, Ruby-crowned Kinglet.

It is not just that the garden offers a patch of greenspace though. What makes the garden a preferred location for our native wildlife are the native plants that inhabit it. The plant species that are native to this region co-evolved with the animals that also live here, seasonally or permanently – they need each other. There is no better example of this then examining the butterfly species reported from the garden. They come to this small area because the plant that they lay their eggs on and that their caterpillar eats can be found in the garden. Some examples include willows for two of our local Swallowtail butterfly species, Ocean Spray for the Lorquin’s Admiral, and Sedum for Moss’s Elfin. In the fall elegant Cedar Waxwings are regularly seen gobbling up the Black Hawthorn fruits, as well as those of some of the other shrubs in the landscape. These fruits are a critical food source for birds that they cannot typically find in urban settings.

The winter garden has value as well: native trees and shrubs offer a year-round source of food to the birds of the region because many invertebrates live on the plants; providing a source of protein to insectivores like Chestnut-backed Chickadees, Red-breasted Nuthatches, and Bushtits. This past winter a flock of as many as fifty Yellow-rumped Warblers spent many months foraging in the garden – always able to find food among the regionally-adapted plants because of the insects feeding on them.

Delta Surprise post

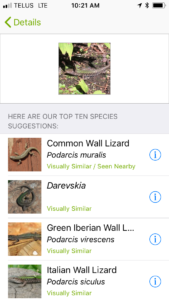

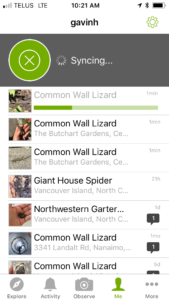

I don’t expect to get new lizard range records in mid-November, especially since the weather has been so grey and cool. This month it seems we have had wind storm after wind storm. Our northern alligator lizard (Elgaria coerulea) should be down for winter—maybe an occasional one will appear on really warm days. Common wall lizards (Podarcis muralis) will emerge, but only when it is sunny. I have seen wall lizards active in sun-exposed locations when the air temperatures are only 5–7°C. But since I have been indoors, I have resorted to correcting United States lizard misidentifications on iNaturalist.

This Monday morning (November 16th, 2020) is grey and cold, and another wind storm is due tonight. But to my surprise, I received an email from Nicole Greenbaum at Paridon Horticultural Ltd. in Delta, BC. She found a lizard in the company’s tropical greenhouse and had correctly identified it as a western fence lizard (Sceloporus occidentalis). Nicole’s discovery is western fence lizard #2 for British Columbia (and Canada).

Canada’s second confirmed western fence lizard; photo by Nicole Greenbaum.

The greenhouse is heated throughout the winter, and so if they are not able to catch this little lizard, it will have quite the winter. Of course I have asked them to catch it to represent BC’s first specimen for the museum collection. Photos are useful, but a specimen is better.

Who wouldn’t want to live in a tropical greenhouse? Photo by Nicole Greenbaum.

This lizard is a juvenile, with a body just over 3 cm. From the photos, I can’t tell whether it is male or female. But the record is now in iNaturalist.

It is possible that a female laid eggs and even more are in the greenhouse, but most likely, this is a single stowaway that came in with a shipment of plants. We have no idea where it originated, nor when it arrived. The greenhouse has not received plants from the United States in some time (it is 2020 after all), so the lizard has likely lived there all summer. I suppose that is effective, pesticide-free insect control.

I wonder when the next one will make its way north of the United States border?

A Tale for COVID Time

I have always believed that culture can transform, art can heal and history holds a mirror to ourselves and our time—thus my deep love for the study of history, arts and culture.

This current unsettling time of global pandemic crisis easily evokes feelings of insecurity and fear. It is a time of racism and uprisings against racism and other forms of discrimination. When I was given a small public space to share my work, I wondered what would be helpful when facing the challenges of our time.

The Royal BC Museum’s special Pocket Gallery A Tale of Two Families: Generations of Intercultural Communities and Family Lessons conveys a special message for the time of COVID. It assures us other people have not only made it through harsh times but have built legacies of success and community support.

Due to historical exclusion and colonial record-keeping practices, few families from settler minority groups can trace their histories back to the gold rush period that began in 1858. Since 2016, I have worked with two families that can: one French Canadian and the other Chinese Canadian. Their stories reveal rarely recorded generational continuities from the gold rush era to the present day. These families have survived times of great adversity, including the Great Depression and the Chinese exclusion era, to build lasting legacies in BC. What has kept the two families going for generations and through difficulties? What has allowed them to continue to grow and prosper today?

A deeper look at the family histories through the family members’ lenses reveals patterns in how the two families persisted through generations. Both families emphasize education, intercultural community building and kindness as family values. Their ideals resonate with our shared experiences and collective values as Canadians. During times of extraordinary challenges, such core values can shape people’s response. The stories of the Guichon and Louie families exemplify resilience through hard times in British Columbia history. Their family lessons are British Columbians’ strength.

On September 23, 2020, the museum hosted a special COVID-safe appreciation event for the featured families and communities of this Pocket Gallery. Maurice Guibord, président, Société historique francophone de la Colombie-Britannique, shared on video the significance of the Guichon family history.

Ms. Hilde Rose, the only living third-generation ranch operator, spoke on behalf of the Guichon family. With her husband Guy Rose, who was a third-generation Guichon, she operated the Quilchena Cattle Co. and the historic Quilchena Hotel for decades.

Mr. Alan Lowe, board chair of the Victoria Chinatown Museum Society and long-time beloved leader and former mayor of Victoria, spoke on behalf of the Victoria Chinatown communities to stress the importance of Chinatown history and the need to preserve it with a new museum in Victoria’s Chinatown.

Mr. Brandt Louie spoke on behalf of the Louie-Seto family as a direct descendant of the pioneer families of the Louies, Setos and Lees in BC, and of the Lews from the United States. He is also the third-generation leader of the H.Y. Louie Family Co. Ltd. His full speech can be found here.

The families’s joined commitment to education, intercultural community building and kindness resonate with our shared values as Canadians. These core values can help us shape our response during COVID time and the fight against discrimination through intercultural understanding and the pursuit of social justice.

Nature during COVID post

Royal BC Museum Biodiversity Research During the Pandemic

Nature is unrelenting. The zoonotic origin of the SARS-CoV-2 novel virus responsible for COVID-19 is a powerful reminder of the connections between human activities, health and biodiversity. As I write this, the COVID-19 pandemic continues to impact all aspects of human society, while the urgency to document, understand and protect biodiversity remains unabated. Museums in particular face the dual challenges of keeping the public engaged and maintaining their research programs. In many institutions, fieldwork, normally a major component of research activities during the summer months, has had to be postponed. Many aspects of learning, public engagement and curation of collections have moved online.

Researchers at the Royal BC Museum are considering the direct and indirect consequences of the pandemic on biodiversity while continuing to meet the challenges of biodiversity research. Aside from anecdotal reports (indicating, for example, that in many places biodiversity may be benefitting from reduced human activity), it is too early to provide a definitive answer to how the pandemic is affecting biodiversity. Given time, and with ongoing communication among scientists in natural history collections and the wider scientific community, this question can be answered by mobilizing and using biodiversity data found in natural history collections.

Ongoing communication of natural history collections is important, especially during this challenging time. Many people experience natural history collections only as museum exhibits. In this context, it can be difficult to visualize museum collections as baseline biodiversity data that are fundamental to diverse scientific fields. However, natural history specimens constitute the data for documenting biodiversity and constructing phylogenies, and they address evolutionary, ecological and biogeographic questions. Additionally, possibilities extend beyond the physical specimen, and may include genomic, behavioural and occurrence data. Therefore it is crucial that collections be maintained, that they grow, and that their data be continually enriched and shared. Through collections, we can improve our understanding of evolving species interactions, including those of pathogens and their hosts, which can help to better predict the risks of novel zoonotic diseases.

What about fieldwork? To cope with the travel restrictions and safety conditions surrounding the pandemic, some researchers have adopted different strategies. For example, in place of large-scale, rapid, people-intensive biodiversity surveys, some locations are studied in great detail over time, with fewer people. One project is the Quadra BioMarathon, conducted by researchers from the Hakai Institute to assess the diversity, abundance and composition of plankton just offshore from Hakai’s Quadra Island facility. The Royal BC Museum provides taxonomic expertise and advises on collection, preservation and identification of specimens.

Curators, collection managers and other researchers at the Royal BC Museum continue to work on collections, expanding, refining and making accessible the data through online collaborations with colleagues from as close as across town or as far as halfway across the globe. We are also committed to making biodiversity data and knowledge accessible to our diverse communities online.

Ongoing projects by Royal BC Museum researchers include taxonomic analysis, linking specimens to nucleotide, genome or protein data, and making data accessible through the Royal BC Museum online database.

Useful links:

GBIF Global Biodiversity Information Facility

iDigBio (Integrated Digitized Biocollections

Royal BC Museum Natural History Curators and Collection Managers

Dr. Victoria Arbour, Curator, Palaeontology

Dr. Henry Choong, Curator, Invertebrate Zoology

Dr. Joel Gibson, Curator, Entomology

Dr. Gavin Hanke, Curator, Vertebrate Zoology

Claudia Copley, Collections Manager and Researcher, Entomology

Heidi Gartner, Collections Manager and Researcher, Invertebrates

Piranha! post

“Don’t let it loose.” That is the message to all pet shops in the province. Shoppers should see the logo that the Inter-Ministry Invasive Species Working Group (IMISWG) asked pet shops to display:

But clearly this message is not getting through.

A blue-eyed panaque was caught in a ditch leading to Shawnigan Lake.

A pacu was caught in Green Lake, Nanaimo.

An albino oscar was caught in Chemainus.

A flowerhorn cichlid was found in Kelowna. Flowerhorns are a man-made hybrid and do not exist in the wild.

Goldfish and rosy-red (fathead) minnows appear in BC with alarming regularity.

All of these abandoned animals originated in the pet trade.

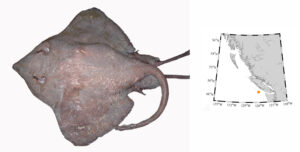

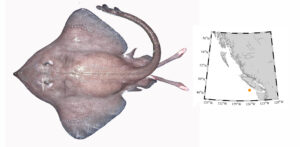

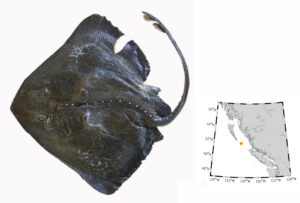

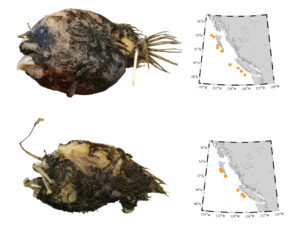

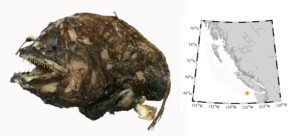

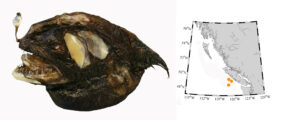

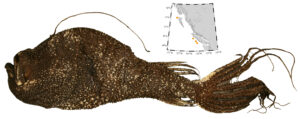

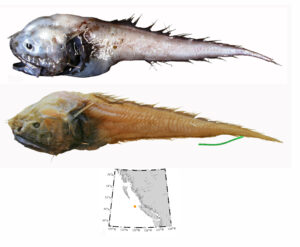

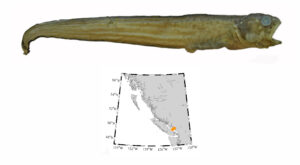

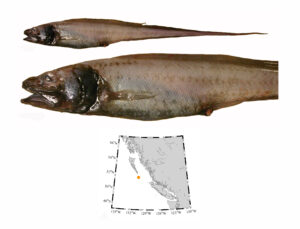

And in 2019, two redbelly piranhas (above, the caught in September; below, the one caught in July) were found in Westwood Lake in Nanaimo. This is a South American species with a famous reputation, exaggerated by several really bad B-movies.

Piranha also may have been released in Langford Lake—a fish enthusiast who routinely dumped his piranha when they grew too large was reported by a friend. We are fortunate that piranhas won’t survive our winters and that most BC lakes are too cold to sustain them even in summer. However, it does show the frequency with which pets get dumped, and you have to wonder what motivates people to abandon pets, especially pets that are potentially harmful to the environment (and in this case, to people).

According to Fuller et al. (1999), the native range of the redbelly piranha is lowland central and southern South America east of the Andes, including the Amazon and Parana basins and the coastal drainages of Brazil and Guianas. In North America, the species has been found in Florida, Hawai’i, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Texas and Virginia. You can bet all of these are aquarium releases. Individual white piranha (S. rhombeus) also have been released in Florida, and a sinkhole pool at a Florida tourist attraction was stocked intentionally in the 1960s. The pool supported a population for about 14 years before state officials used rotenone to wipe them out. Other piranha, which were not identified, have appeared in California, Connecticut, Florida, Idaho, Illinois, Iowa, Kentucky, Missouri, New Hampshire, New York, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Utah and Washington.

I don’t think we have a synopsis of records in Canada, but I know pacu and silver dollars—relatives of the piranha—have appeared in Manitoba and Ontario, so who knows how many piranha have also been dumped in this country.

If you don’t want a fish, take it back to a pet shop, find it a new home, or if you have to, have it euthanized humanely. Our waterways are cool to cold, and it is unfair to make tropical fish suffer in cold water. And released tropical fish present a disease risk to our native fishes. Don’t release pets. BC becomes less beautiful with every abandoned animal (and aquarium plant—but that is another story entirely).

Reference:

This is the month that the garden explodes with food—and lizards. Everywhere you look, there is food to harvest. We try to weigh everything to get an idea of the cash value in our garden, but sometimes you just have to eat things right off the vine.

Our tomatoes are ripening daily, with the Pineapple Cherry tomatoes at their delicious best now that we are nearing the end of August. Several of our tomatoes are not your typical variety: the Snow White ripens a pale cream-white colour, Black Prince are red-brown when ripe, and then we have the Green Zebra, which (as the name suggests) is striped green when ripe. They are all fantastic.

We have already started saving seeds for next year. The seeds are left in water for a few days to simulate the rotting fruit, then we drain and dry to store seeds over winter.

Zucchini, cucumbers, squash and melons are all producing fruit, though I don’t think the melons will amount to anything. Our pumpkin went nowhere. C’est la vie dans la grande ville. We will buy pumpkins to carve for Halloween and support a local grower in the process.

Cabbages are being converted to sauerkraut. Some cucumbers were grown specifically for pickles, others to eat straight up.

We have collected over 6 kg of blackberries, and our strawberries are still producing. The yellow raspberries produced just enough fruit for all three of us to enjoy a quick snack.

Apples are nearly ready. And if this wasn’t enough fruit, our neighbours have offered some pears—we just have to pop over and pick them.

A grey squirrel has figured out that our garden has loads of food and destroyed our mini-sunflowers. It also has been eating plums, leaving sticky scraps on our compost bins. That is part of gardening—sometimes you have to share. Wasps and house finches have nibbled on their fair share of the blackberries.

Even without our greenhouse—it got crushed by the snow last winter—we still grew some nice peppers, and the Italian parsley and New Zealand spinach are growing well. Carrots are our biggest failure; only a few grew.

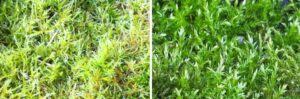

Lizards have hatched—everywhere you look, a lizard the size of my pinkie finger darts off to hide in our rock walls and garden beds. The adults are still here too—but they seem to be less interested in basking in the midsummer’s sun. Perhaps the females don’t need to bask so much now since they are not carrying developing eggs.

Much of the work now shifts indoors. Berries and tomatoes are being frozen for winter use. Beans are being shelled and left to dry for winter chili, stews and soup. Onions are pulled and drying on the deck so they will store well. Only the Scarlet Runner Beans are still growing and will be picked later in the season.

The bean plants that are finished are now pulled and left on the ground to decay and add substance to the soil. We still need to harvest the potatoes in our front garden, and then in the next few weeks we will plant a cover crop. Once the cover crop has grown a few centimetres, we will cover it with a tarp to let worms and other recyclers enrich the soil.

And even while the harvest is in full swing, we are planting lettuce and kale starts for autumn and winter. It is amazing to be able to walk outside in winter and get fresh produce when you need it.

This has been a good summer for food production. We have hundreds of dollars in produce, with over $50 in blackberries alone at current market rates. We added oak-leaf mulch and some horse manure early in the season, watered when we needed to, and that is about it. Even a modest city garden can produce plenty of good clean food.

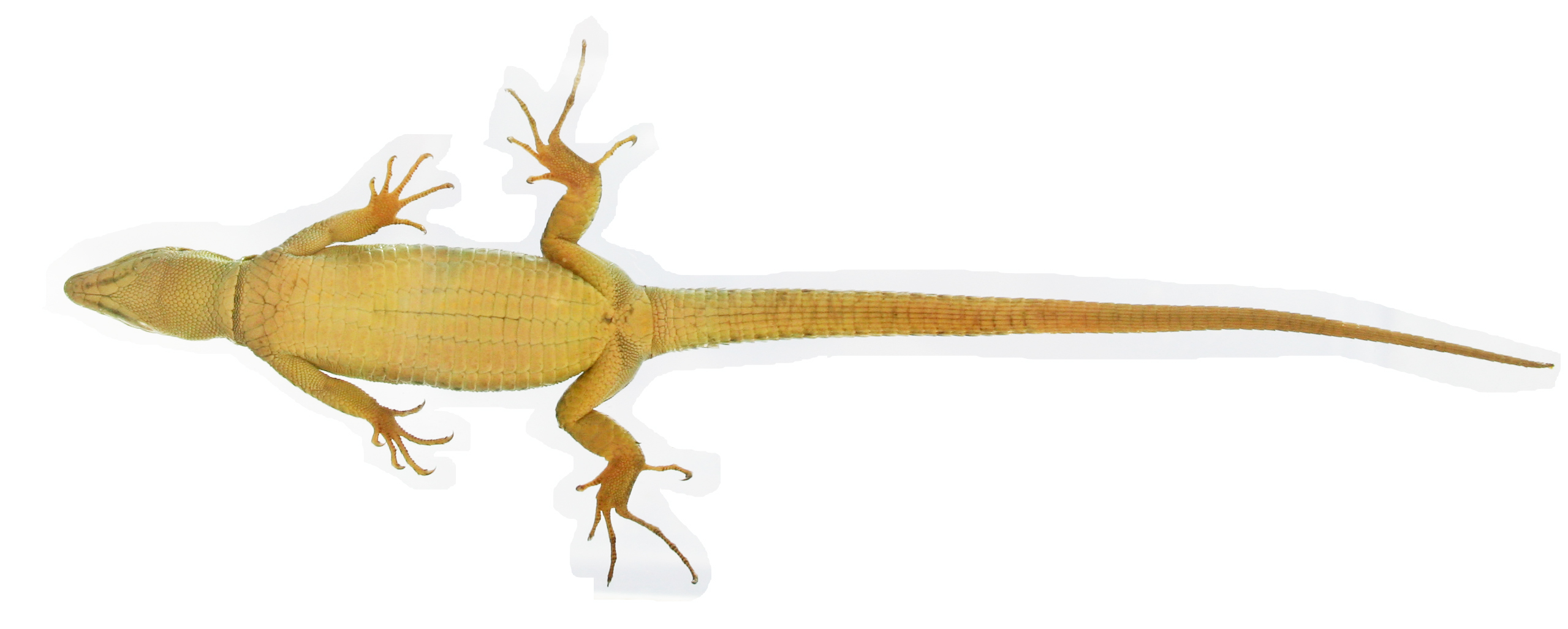

Hatchlings Happen post

I have been watching a female lizard in my garden slowly increase in girth as her eggs developed in May to early June. I recorded each day whether she was gravid or not, and noted when she lost her tail. Simple observational science is something I could do to better understand common wall lizard biology in BC while working from home.

My notes around the time I think eggs were laid went as follows:

June 5 – basking on rocks, 80% tail lost in the last few days, still looks gravid.

June 6 – not sighted

June 7 – not sighted

June 8 – not sighted

June 9 – rainy, cold, not sighted

June 10 – basking on rocks, has folds of skin along the flank suggesting eggs laid.

I have watched our resident female wall lizard as her tail regenerated, and I saw her again yesterday (July 30) sporting a tail several centimeters shorter than the original.

I patrol the garden daily to see what the lizards are doing, and when and where they are active. My wife will confirm this obsessive behaviour. But this morning (July 31) I dropped my daughter off at a day camp, and on return home, as I walked up my driveway, I spotted our first hatchling.

I gasped—I am not ashamed to admit it.

Lizards invaded our garden in 2019, and one year later we have a home-grown baby lizard. It looked pretty comfortable in its new habitat, so perhaps it hatched yesterday (July 30) or the day before. And there is no way to tell, without perhaps a series of DNA samples, whether this hatchling came from the female I have been studying, or whether some other female dug a nest in our garden. Young lizards leave their parents’ territory to avoid cannibalism, so this one may head for the hills. But it does give us an estimate of timing between egg deposition (somewhere between June 6–8, assuming eggs were not laid June 9 when it was cool and rainy) and the first appearance of hatchlings July 31.

Females mature in their second year and can have one to three clutches of eggs each summer, depending on latitude and local conditions, with clutches ranging from 2 to 10 eggs. In nature, incubation ranges from 6–11 weeks. Embryo development is about halfway at oviposition, and females bury eggs in sandy or crumbly substrates at the end of 10–20 cm tunnels (Van Damme et al. 1992). In a laboratory experiment, temperature dramatically changed incubation times, with wall lizards incubated at 32–35°C hatching 10 days earlier than lizards incubated at 28°C, and over five weeks earlier than those incubated at 24°C (Van Damme et al. 1992). We had a cool spring, and I am not surprised then that 50–52 days passed between the first evidence that the female had laid eggs and the appearance of a hatchling.

Hatching success is high in the 24–28°C incubation range, and Van Damme et al. (1992) suggested 28°C is the best trade-off between hatching success, incubation rate and hatchling health. I wonder how many more hatchlings will appear in the garden?

For more information:

Van Damme, R., D. Bauwens, F. Braña and R.F. Verhyen. “Incubation Temperature Differentially Affects Hatching Time, Egg Survival and Hatchling Performance in the Lizard Podarcis muralis.” Herpetologica 48, no. 2 (1992): 220–228.

Ooooohhh Barracuda post

It is 2020, and people are asking whether this year will get any stranger.

How about barracuda in BC waters? Does that qualify?

I received several emails and other messages today (July 10) noting that a 5.4 kg barracuda had been caught off Vancouver Island this week. This is a really cool record, and I hope it’s added to iNaturalist.

Pacific barracuda (Sphyraena argentea) from San Diego, California. Photo by Darren Baker, uploaded to Fishbase IMG-20120830-00071.jpg.

Pacific barracuda (Sphyraena argentea) are known to range all along our coast, and as Alaska-based biologist Scott Meyer notes, they range north to Alaska during El Niño years. The first record from Alaska (off Kodiak Island) dates back to 1937, when a school of barracuda was sighted, though only one was caught. The surface waters of the Eastern Pacific Ocean must have been warm that year, because a barracuda also was caught off Sooke, British Columbia. Another barracuda was found in Prince William Sound, Alaska, in 1958. In BC they are known also from Queen Charlotte Sound and the Prince Rupert area (see Hart 1973). Pietsch and Orr (2019) detail several barracuda records from the Salish Sea in their magnum opus, Fishes of the Salish Sea.

The first record along the BC coast was a specimen cataloged at the Royal BC Museum (RBCM 33), caught at Otter Point in Sooke, July 27, 1904. It is the only Pacific barracuda in the RBCM collection. According to Peitsch and Orr (2019) the earliest record of Pacific barracuda in the area comes from Gig Harbor, Puget Sound dating back to 1878.

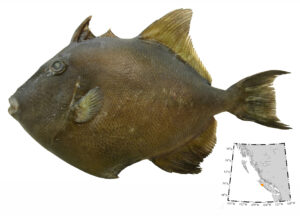

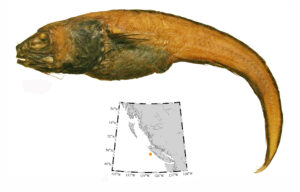

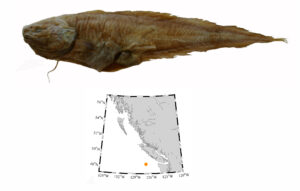

I wouldn’t mind another specimen for the museum collection to accompany the 1904 specimen and our other warm-water strays: the louvar and finescale triggerfish found here in 2014, the North Pacific argentine from 2010 and the spotted porcupinefish from 2019.

I wonder what fish is next? Maybe we will get more hammerhead sharks? They were seen off Ucluelet in 1952 and 1953. Sure would be neat to have them here again.

References:

Carl, Clifford C. “The Hammerhead Shark in British Columbia.” Victoria Naturalist 11, no. 4 (1954): 37.

Cowan, Ian McTaggart. “Some Fish Records From the Coast of British Columbia.” Copeia 1938, no. 2: 97.

Hart, John Lawson. Pacific Fishes of Canada. Fisheries Research Board of Canada Bulletin 180. 740 p.

Quast, Jay C. 1964. “Occurrence of the Pacific Bonito in Coastal Alaska Waters.” Copeia 1964, no. 2: 448.

Pietsch, Theodore, and James. W. Orr. Fishes of the Salish Sea, Puget Sound and the Straits of Georgia and Juan de Fuca. Victoria: Heritage House, 2019. 1032 pages.

Van Cleve, Richard, and W.F. Thompson. “A Record of the Pomfret and Barracuda from Alaska.” Copeia 1938, no. 1: 45-46.

Authors: Robert J.WilliamsaAlison M.DunnaGavinHankebJoel W.DixonaChristopherHassalla

ABSTRACT

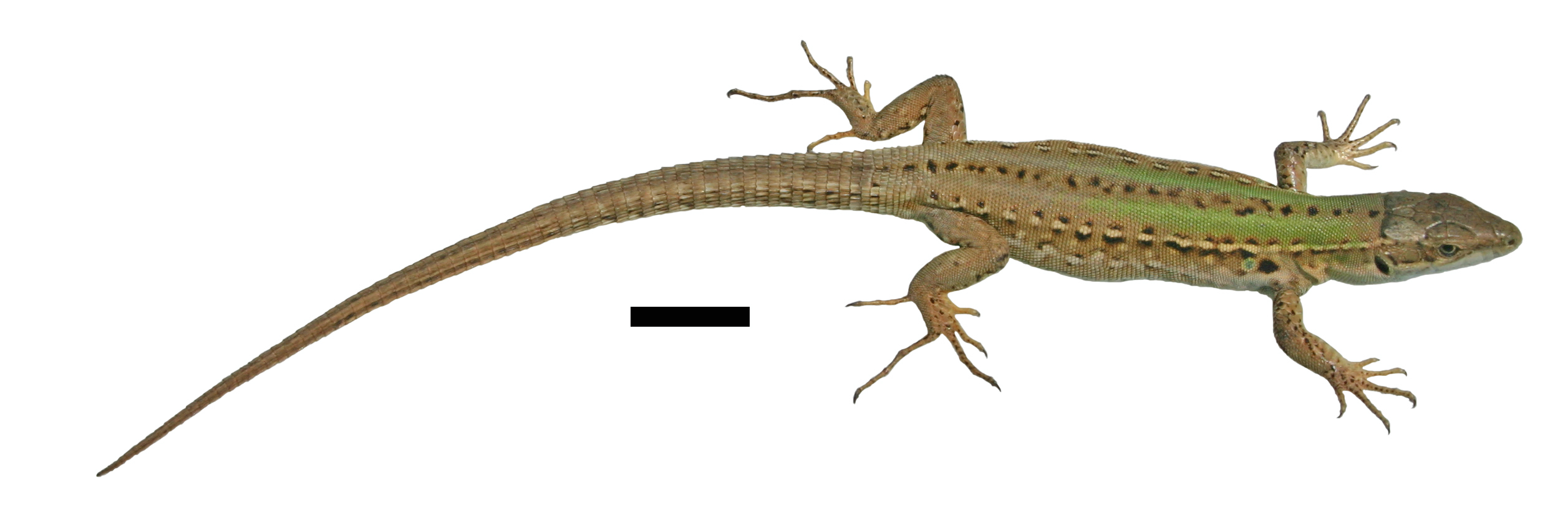

The human-assisted movement of species beyond their native range facilitates novel interactions between invaders and native species that can determine whether an introduced species becomes invasive and the nature of any consequences for native communities. Avoiding costly interactions through recognition and avoidance can be compromised by the naïvety of native species to novel invaders and vice versa. We tested this hypothesis using the common wall lizard, Podarcis muralis, and the native lizard species with which it may now interact in Britain (common lizard, Zootoca vivipara, sand lizard, Lacerta agilis) and on Vancouver Island (northern alligator lizard, Elgaria coerulea) by exploring species’ responses (tongue flicks, avoidance behaviour) to heterospecific scent cues in controlled experiments. The tongue flick response of P. muralis depended on the different species’ scent, with significantly more tongue flicks directed to E. coerulea scent than the other species and the control. This recognition did not result in any other behavioural response in P. muralis (i.e. attraction, aggression, avoidance). Lacerta agilis showed a strong recognition response to P. muralis scent, with more tongue flicks occurring close to the treatment stimuli than the control and aggressive behaviour directed towards the scent source. Conversely, Z. vivipara spent less time near P. muralis scent cues than the control but its tongue flick rate was higher towards this scent in this reduced time, consistent with an avoidance response. There was no evidence of E. coerulea recognition of P. muralis scent in terms of tongue flicks or time spent near the stimuli, although the native species did show a preference for P. muralis-scented refuges. Our results suggest a variable response of native species to the scent of P. muralis, from an avoidance response by Z. vivipara that mirrors patterns of exclusion observed in the field to direct aggression observed in L. agilis and an ambiguous reaction from E. coerulea which may reflect a diminished response to a cue with a low associated cost. These results have significant implications for the invasive success and potential impacts of introduced P. muralis populations on native lizards.

Keywords

See full article

See Claudia’s Research Gate profile, which includes her recent publications and peer reviewed articles.

Abstract

See full article

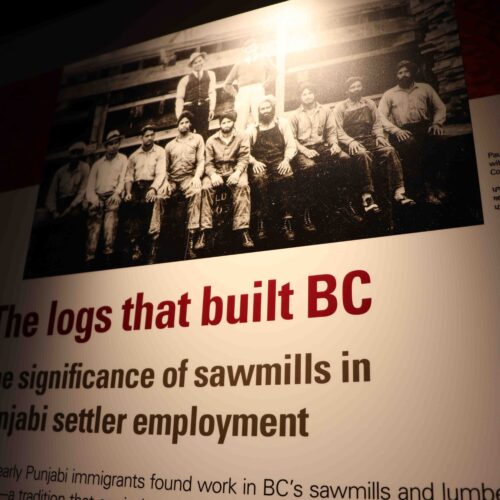

This article examines the Punjabi Canadian Legacy Project (PCLP), a partnership project between the Royal British Columbia Museum and the South Asian Studies Institute at the University of the Fraser Valley, as a case study of heritage from below. The project is based on community action research and practices, joining forces of memory, research, and community institutions, organisations, and groups. Considering ‘heritagisation’ as a process of heritage building, and drawing on their experience as practitioners on this project, the authors argue for the need to consider the vast diversities within and among communities, and the need to work on ‘heritagisation’ through ongoing dialogic engagement.

Through a myriad of continuous dialogues and inherent challenges, the process and progress of the PCLP is shaped by this dialogic engagement. As an ongoing project, the PCLP demonstrates how a network extended to diverse participants with shared goals can emerge through the organically developed heritagisation process encouraged by the partners’ collaborative efforts in an experimental model for community work by memory and research institutions.

See full article

A Growing Tale post

Working at home has allowed me to pay plenty of attention to the individual lizards in our garden. I can watch where they go, locate preferred basking spots in the garden, watch what they eat, and try to figure out when eggs have been deposited and, later, when hatchlings will emerge.

Individuals are easy to identify based on size, sex and scarring. Most lizards have tails that have regrown, and the relative length of the original tail helps identify each animal.

Our gravid female had a perfect tail until recently, but on June 5, I noticed that she had been attacked. Her tail was now less than a quarter of its original length. The stump was still fresh and had not grown over with new skin.

We have several domestic cats vying for our garden (they also like using our garden beds as a litter box). The complexity of our garden attracts lots of birds, and it’s prime hunting territory for pudgy suburban felids to roam and kill at will. One cat (we know him as Meow, because that is what he said when we asked him his name), is a frequent visitor to our yard. He is likely the local lizard lacerator.

It appears that the growth is slow at first as the tail heals and the tissues organize themselves, but between June 19 and July 4, the tail grew an estimated 26 mm. The regrown tail will never be as long as the original, but it can be shed again if the lizard is attacked.

Nature is amazing. Field bindweed, an invader from Eurasia, grows at an alarming rate in our garden. Beans can go from a mere sprout to a massive flowering plant in a few weeks. And we can add lizard tails to our list of fast-growing crops.

When we harvest leafy veggies like lettuce, chard or New Zealand spinach, we take a few leaves for our meal and leave the rest of the plant to grow. The would-be predator attacking the wall lizards in our yard is also harvesting tails and letting the lizards regrow a new crop. I don’t think domestic cats have the mental capacity to intentionally farm lizard tails, but that is effectively what is happening.

Robb Bennett¹,², David Blades², Gergin Blagoev³, Don Buckle⁴, Claudia Copley², Darren Copley², Charles Dondale⁵, and Rick C. West⁶

1 Corresponding author – robb.bennett@shaw.ca

2 Natural History Section, Royal British Columbia Museum, 675 Belleville St, Victoria, BC, Canada

3 Centre for Biodiversity Genomics, University of Guelph, Guelph, ON, Canada

4 16-3415 Calder Crescent, Saskatoon, SK, Canada

5 Canadian National Collection, Agriculture & Agri-Food Canada, 960 Carling Ave, Ottawa, ON, Canada (retired)

6 6365 Willowpark Way, Sooke, BC, Canada

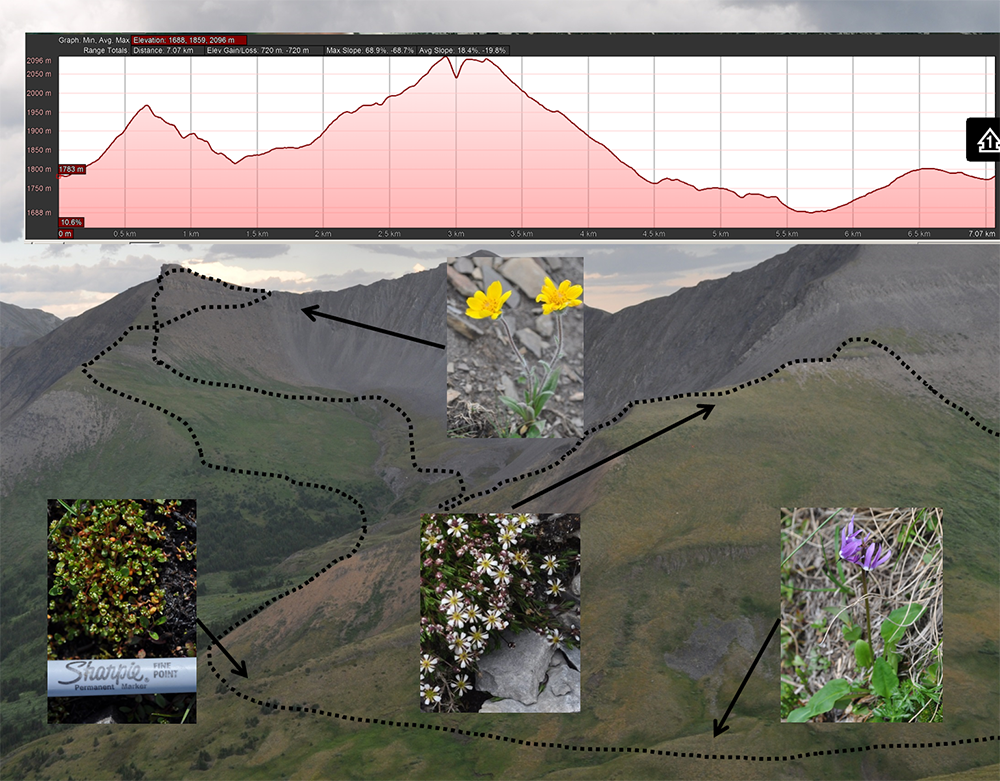

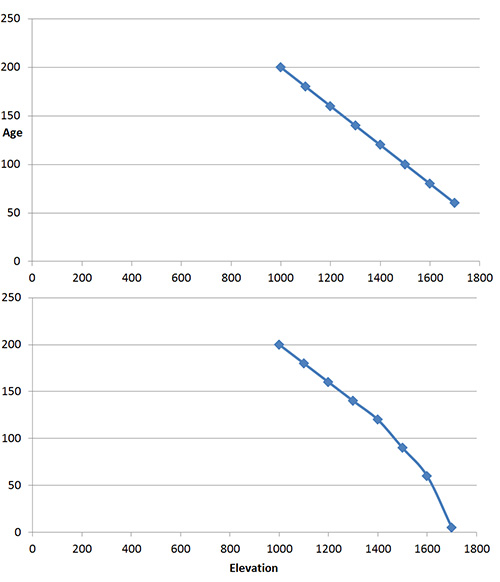

Abstract:

In 2006, the Royal British Columbia Museum began systematically documenting the full diversity of British Columbia’s spider fauna. Initially, museum specimens and literature records were used to update an existing checklist and identify poorly sampled habitats in BC. Annual field surveys of spiders, primarily targeting alpine and subalpine habitats, began in 2008; barcode identification of previously unidentifiable specimens commenced in 2012. These efforts have resulted in significant increases in the area of BC that has been sampled for spiders, the number of species documented in the BC checklist, and the number of specimens in the RBCM collection. Many of the additions to the checklist represent the first Canadian or Nearctic records of those taxa or are undescribed species. By 2017, data from more than 9000 spider specimens had been entered into the RBCM database.Data from many specimens, however, remain unrecorded and currently (2017) the RBCM collection is estimated to house more than 90 000 specimens. The number of species recorded in BC has climbed from 212 in 1967 through 653 in 2006 to 859 in 2017. Here we present BC localities data and general global distributions for those 859 taxa. The progress of the RBCM’s work has made the RBCM an important repository of western Nearctic spiders and shown that British Columbia is an important area of Nearctic spider diversity.

See full article

ABSTRACT

The distribution of northern British Columbia alpine plants is poorly documented. To improve our understanding of the flora of this vast, remote region, we collected more than 11 000 specimens from 65 mountains during 2002–2011. Most of these locations had not been visited by botanists. Of the more than 400 species we have collected, two are new to the province, others represent significant range extensions. Twelve species share elements of a disjunct distribution that has apparently not been previously recognized and consists of three regions: (1) northwestern North America; (2) Beartooth Plateau; and (3) northern Colorado. These 12 species appear to be absent from the extensive areas of suitable habitat that occur in the intervening areas. The most reasonable explanation for this pattern is that these species, adapted to arctic–alpine tundra conditions, migrated throughout western North America during the Pleistocene, a time when suitable habitat was much more widespread than now, and subsequently went extinct in many areas as the climate warmed during the Holocene.

Keywords: arctic–alpine vascular plants, disjunct, northwestern North America, Beartooth Plateau, northern Colorado

See full article

Abstract

Many plant species comprising the present-day Arctic flora are thought to have originated in the high mountains of North America and Eurasia, migrated northwards as global temperatures fell during the late Tertiary period, and thereafter attained a circumarctic distribution. However, supporting evidence for this hypothesis that provides a temporal framework for the origin, spread and initial attainment of a circumarctic distribution by an arctic plant is currently lacking. Here we examined the origin and initial formation of a circumarctic distribution of the arctic mountain sorrel (Oxyria digyna) by conducting a phylogeographic analysis of plastid and nuclear gene DNA variation. We provide evidence for an origin of this species in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau of southwestern China, followed by migration into Russia c. 11 million yr ago (Ma), eastwards into North America by c. 4 Ma, and westwards into Western Europe by c. 1.96 Ma. Thereafter, the species attained a circumarctic distribution by colonizing Greenland from both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. Following the arrival of the species in North America and Europe, population sizes appear to have increased and then stabilized there over the last 1 million yr. However, in Greenland a marked reduction followed by an expansion in population size is indicated to have occurred during the Pleistocene.

Keywords: ancestral location; arctic flora; circumarctic distribution; migration; species origin.

See full article

Abstract

Aim

Many plants, especially at high latitudes, have both widespread and highly discontinuous geographical distributions. To increase understanding of how such patterns originate, we examine genetic patterns in the arctic–alpine plant Sibbaldia procumbens . We evaluate the contributions of refugia and the role of long‐distance dispersal in shaping the current range of this species.

Location

Northern Hemisphere, especially North America.

Methods

We sampled Sibbaldia from 176 localities, including 168 for S. pro‐cumbens . We analysed sequence variation in three plastid DNA non‐coding regions (the atp I–atp H and trn L–trn F intergenic spacers and the trn L intron), performed Bayesian phylogenetic analyses and statistical parsimony analyses on the combined sequences, and analysed the geographical patterns of haplotype distribution and genetic diversity using data from all populations.

Results

Sibbaldia procumbens probably originated in the mountains of South and East Asia. We identified highly distinct clades in Europe and North America, which overlapped on oceanic islands of the North Atlantic indicating long‐distance dispersal capability. The North American clade included two lineages, one in California and the other widely distributed across the continent and North Atlantic. Haplotype diversity in the latter lineage was markedly higher to the south, suggesting mid–late Pleistocene southward displacement of North American populations with subsequent migration northwards into previously glaciated regions. In Europe, disjunct geographical regions generally harboured distinct haplotypes.

Main conclusions

Multiple Pleistocene refugia for S. procumbens occurred in both North America and Europe. North American refugia existed in California and in the southern Rocky Mountains, but in contrast with most widespread arctic–alpine species we found no evidence for a Beringian refugium. Cryptic refugia may have existed within the Cordilleran Ice Sheet. Episodes of range expansion and contraction and long‐distance dispersal have all contributed to the genetic structure and widespread but fragmented distribution of this species.

See Full Article

I recently spent a glorious sunny day on Willows Beach in Victoria. Staghorn sculpins (Leptocottus armatus) and many small soles raced to deeper water as we walked along in ankle-deep water. The tide was out. People were everywhere, but no one was lifting rocks to see everything hiding in plain sight.

Further up the beach was a line of marine macroalgae (especially Ulva, sea lettuce) stranded by the receding tide. Under each rock you can expect a handful of isopods, as well as shore crabs and small Dungeness crabs that scuttle away, and even the tiniest puddles under a rock sheltered up to 8 fish—sculpins and gunnels. The sun heated the beach, but under the algae-draped rock, water stayed shaded and cool and kept everything alive until the tide returned.

Most pools had tidepool sculpins (Oligocottus maculosus), and most were the typical grey-brown mottled form. But there also were many of these green sculpins—the same species as the typical grey-brown tidepool sculpin. These green sculpins are perfectly camouflaged in patches of sea lettuce.

A bright-green tidepool sculpin sure stands out from its typical grey-brown relatives.

Without the usual coloration to rely on, you have to look more carefully to see whether this is a tidepool or fluffy sculpin (O. snyderi). Fluffy sculpins have cirri (little wispy flaps of skin) along the lateral line in clusters of three to six, and the clusters of cirri follow the lateral line along the flank of the body. This photo—even though it was taken with my old iPhone 6. which performs poorly when taking macro shots—shows that the cirri along the lateral line are only found near the head, and they are single. This clearly is not a fluffy sculpin.

Next time you are on the beach and the tide is out, take some time to explore tidepools and rocky ledges along the shore, and carefully lift some rocks. You probably will find a lime-green sculpin or two. You may also find lime-green penpoint gunnels (Apodichthys flavidus) or rosylip sculpin (Ascelichthys rhodorus). If you are really lucky, you will find sculpins with bright-pink colouration to match coraline algae, or a blue-and-red-banded longfin sculpin (Jordania zonope). Even in this city, there is plenty to see along shore.

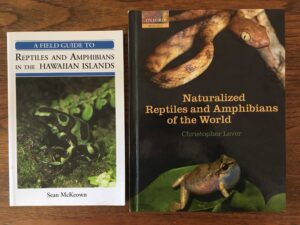

Don’t Fence Me In post

On June 16, I received notification that my blog post on introduced lizards in Hawaii was live on the internet. The last paragraph in that article is about western fence lizards (Sceloporus occidentalis), where I ask people who see them in BC, to report the observation (with a picture if possible), or tag the occurrence in iNaturalist. Western fence lizards were on Matsuda et al.’s (2006) radar as a potential immigrant since the species exists so close to the Canadian border.

Between submitting that blog post and it going live, the plea for lizard sightings was answered. A report came my way of a western fence lizard loose in BC. I had always assumed the first record would surface in the Okanagan region, since several anecdotes from there suggest fence lizards are already present as far north as Oliver. Furthermore, field guides show western fence lizards just south of the Okanagan region (St. John 2002; Stebbins and McGinnis 2018) and Storm et al. (1995) presented a range map for western fence lizards having a straight line at the international border. Lizards don’t recognize political boundaries, so there is no way Storm et al.’s map is accurate. Fence lizards would do really well in the orchards, fence lines and piles of fruit crates of the southern Okanagan.

Instead of the Okanagan, the first record of a western fence lizard in British Columbia came from the Cloverdale area of Surrey, on June 6, 2020.

Our first confirmed western fence lizard was a juvenile, and it had lost its tail to some would-be predator. We have no idea how this lizard arrived in BC; most likely it is a stow-away from south of the international border. It could have been an escaped pet, or maybe there is a population now in the area that has gone unreported. The lizard is still loose, but we are hoping to catch it and add it to the museum collection.

The lizard is strangely coloured for a western fence lizard, but it does have the yellow-orange tint to the rear surfaces of the fore and hind limbs. The other possible look-alike in the region, though not in Canada, is the sagebrush lizard (Sceloporus graciosus), which has white on the undersides of its limbs. Sagebrush lizards are in Washington, but nowhere near as close to BC as western fence lizards (Storm et al. 1995; St. John 2002; Stebbins and McGinnis 2018). The nearest population of western fence lizards in Puget Sound is at Cherry Point, about 27 km south of where the Cloverdale specimen surfaced, thanks to a researcher in 1990 who released a handful of fence lizards to see if a population would get established.

In addition to this Cloverdale record in Surrey, a western fence lizard was reported on iNaturalist, April 2019, at MacNeill Secondary School, Richmond, British Columbia. However, this 2019 report cannot be verified since neither specimen nor photograph are available. Perhaps a second western fence lizard is loose in BC. Maybe it’s a sagebrush lizard. It would be great to get a picture of that Richmond reptile to verify the species.

And I am still not giving up on the Okanagan—if you live anywhere between Summerland and the international border, keep your eyes peeled for fence lizards!

Some background information:

Matsuda, B. M., D. M. Green, and P. T. Gregory. 2006. Amphibians and Reptiles of British Columbia. Royal BC Museum, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada.

Stebbins, R. C., and S. M. McGinnis. 2018. Peterson Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Boston, Massachusetts.

St. John, A. 2002. Reptiles of the Northwest, British Columbia to California. Lone Pine Press, Renton, Washington.

Storm, R. M., W. P. Leonard, H. A. Brown, R. B. Bury, D. M. Darda, L. V. Diller, and C. R. Peterson. 1995. Reptiles of Washington and Oregon. Seattle Audubon Society, Seattle, Washington.