Fieldwork 2018

This year’s fieldwork was our 17th in the alpine of the northern B.C. We made collections from six mountains. The area is so vast and remote and access is difficult, thus few if any biological inventories have been undertaken in many large areas. Many peaks and lakes have no names; in fact there are no names on entire mountain massifs. I feel like we are to some degree just ‘scratching the surface’ of what is out there.

We again worked together with the insect and spider experts at the museum. And we followed our typical approach of setting up camp for 2-3 days and collecting specimens of every species we encounter, being intentional to reach as many different habitats as possible.

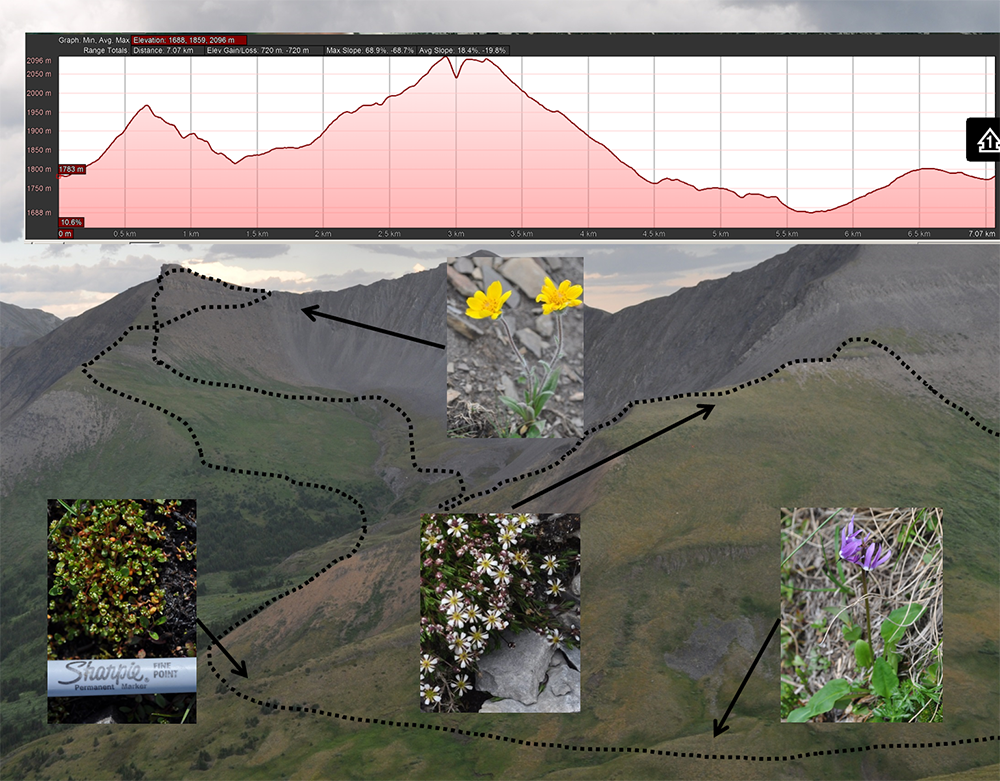

Typical day of hiking (dotted line) and collecting, striving to reach as many habitats as possible. Upper part of figure documents elevation changes during the day. Three of the four plants in this illustration were encountered only once, highlighting the importance of having several botanists in the field and covering as much ground as possible.

At one mountain, Mt. Whitford, we were joined by two staff and a contract photographer of the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative https://y2y.net/about-us and their guest freelance journalist who produces pieces for both CBC and NPR. At a second mountain, south of Tumbler Ridge, we were joined by two staff members of the Tumbler Ridge Geopark, http://tumblerridgegeopark.ca/. What is a Geopark? According to their website “A UNESCO Global Geopark is an area recognized as having internationally significant geological heritage.” These groups are all interested in knowing as much as possible about the biota of these areas and we will share everything we learn with them.

As we have in the past, we contacted the local indigenous groups and informed them of our work and will provide them species lists when the identifications are complete.

We are often asked if we notice any of the effects of climate change during our fieldwork. Treeline is controlled by temperature, not elevation and is highest at the equator – where temperatures are warmer at higher elevations – and becomes lower and lower further north and south. One likely consequence of a warming planet is that forests will advance into the alpine, reducing the available habitat for tundra plants that generally require open, i.e. non-shaded habitats.

Young trees in alpine meadows at 1750 m north of Laurier Pass, Graham-Laurier Provincial Park. Note the dark skies of a storm about to dump

For a number of years I’ve noticed small trees in the alpine and of course wonder if their appearance is related to climate change as a consequence of global warming. I’ve also noticed the absence of dead trees. The absence of dead trees may mean that tree populations in the alpine are relatively young, compared to lower elevation forests where trees have been growing and dying for thousands of years.

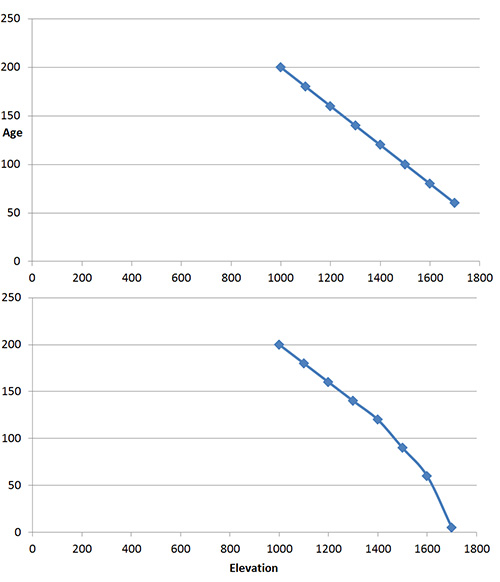

Two hypothetical graphs of tree age versus elevation curves. The upper one portrays trees that become gradually younger with elevation gain, much as one might expect if treeline was moving higher gradually. The hypothetical curve on the lower graph describes a more abrupt change, i.e. what one might expect if tree line had been stable for a relatively long period of time, slowly moving to higher elevations, then suddenly and relatively recently, young trees became established higher than before.

But a further question is this: have the young trees in the alpine arrived relatively suddenly and recently because of recent rapid increase in global temperatures, or are they gradually moving upwards due to a long term warming trend that has been taking place ever since the end of the Pleistocene, ca. 13,000 years ago? Dating trees by their growth rings could provide the answer by measuring the ages of trees along an elevation gradient from well below tree-line into the alpine. I suspect this kind of research is underway.

Every year we seem to encounter botanical surprises, either range extensions or species that we haven’t seen before. I like these kinds of discoveries because distribution patterns tell us something about the history of the landscape and when those distribution patterns are found to be different from what was previously known, the background story might change.

One notable collection this year was Dodecatheon frigidum (northern shootingstar) that we collected in northern Graham Laurier Provincial Park, about 200 km south of where it has been collected previously near the Alaska Highway. We’ve visited 8 mountains in the intervening area and have not encountered this species. What does this occurrence mean? Have we merely overlooked it in other areas or is it in fact not present for this 200 km distance?

Another interesting find was Claytonia lanceolata (western spring beauty) which I saw in the alpine for the first time. Previously I had encountered it at lower elevations in Botanie Valley north of Lytton. Indigenous people in the southern interior of BC eat the tubers either fresh or cooked. Perhaps indigenous people in the Tumbler Ridge area also eat the tubers. I haven’t had a chance to ask local people or to investigate the literature.