Human History

- GR-3346.37 2021 Speech from the Throne

- The archives’ most recent record, created less than a year ago·

- GR-3518 Records of the Provincial Health Officer *

- This accrual covers the records of Dr. Perry Kendall, who served as the Provincial Health Officer from 1999 to 2018. The records address the health of Indigenous populations, water quality and pandemic influenza preparation among other public health topics.

- GR-3676 and GR-3677 Cabinet committee records and Premiers’ records*

- Large accruals were added to these series this year, documenting cabinet proceedings and priorities. Most records up to 1991 are publicly accessible.

- GR-3890 Drafting legislation case files*

- Comprehensive records covering all aspects of the process for drafting and approving provincial legislation. The records relate primarily to the 1970s and 1980s.

- GR-3948 Notebook related to the Tsilhqot’in War

- This delicate and difficult to decipher notebook relates to the events of the 1864 Tsilhqot’in War. It includes a diary of a group of settlers attempting to apprehend the Indigenous men allegedly involved in the deaths of several settlers.

- GR-3996 Conservation Officer Service major investigation case files*

- The series consists of the major investigation case files of the Conservation Officer Service between 1992 and 2007. Major cases are serious in nature and address complex issues such as trafficking animal parts, big-game poaching, illegal fishing or guiding, or selling animals for human consumption that are procured illegally.

- GR-3999 Environmental Appeal Board records*

- This series includes appeal files submitted to the Environmental Appeal Board and its predecessors: the Pollution Control Board and Pesticide Control Board. The records document the government’s management of the environment.

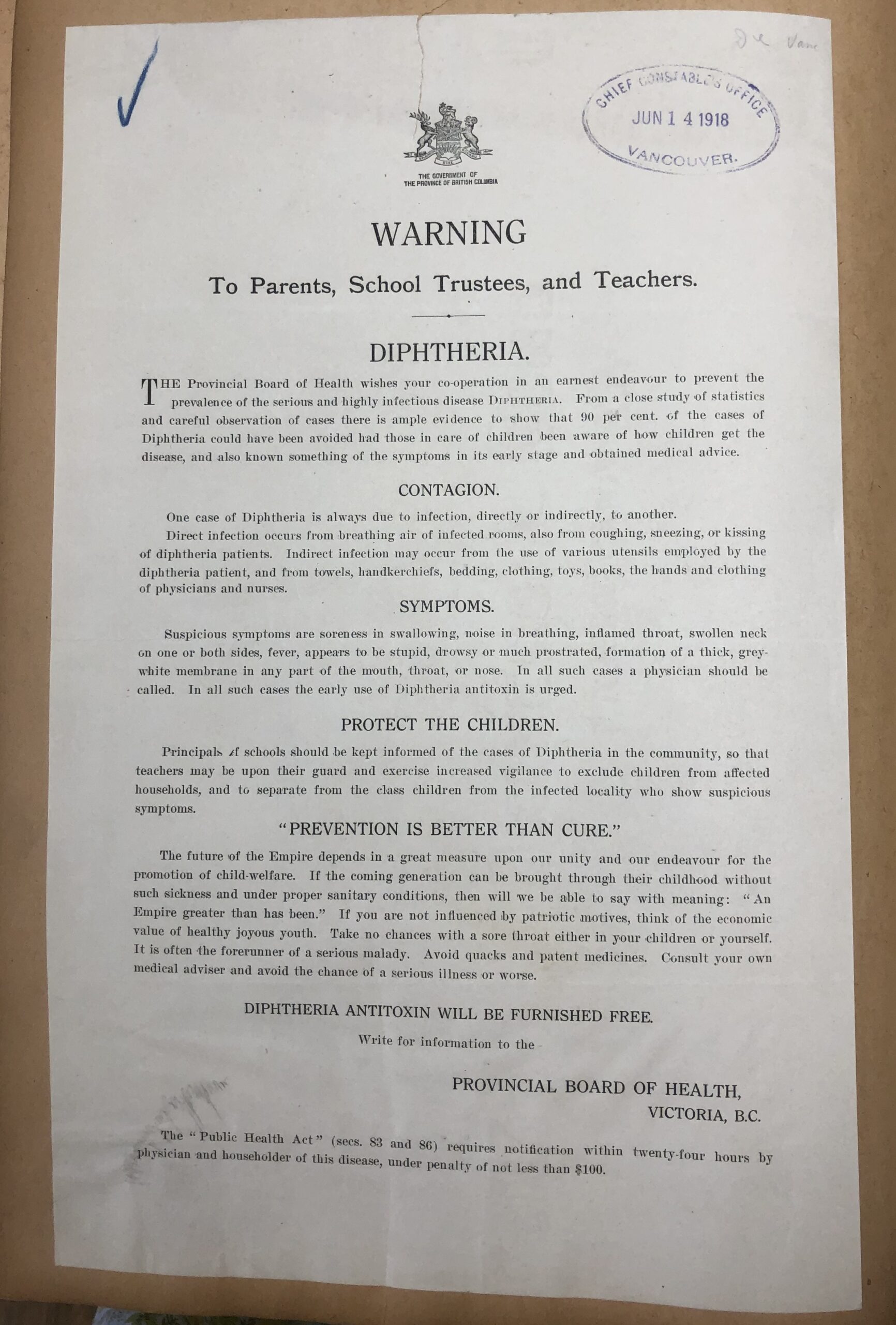

- GR-4000 Provincial Police circulars and wanted posters*

- This series includes a variety of informational posters for alleged criminals wanted across Canada and the United States. Many of the records are pasted into indexed volumes, serving as simple criminal record “databases.”

- GR-4002 Forest Practices Board meeting files*

- This series includes records of the Forest Practices Board which serves as the independent watchdog for sound forest and range practices in the province.

- GR-4005 Conservation Officer Service wildlife attack final reports*

- This series consists of final reports summarizing wildlife attacks on humans created by the Conservation Officer Service between 1991 and 2012. They illustrate the evolution of wildlife attack investigative technique, causes of wildlife attacks, and methods used to dispatch wildlife.

- GR-4008 BC Ambulance Service and air evacuation major accident and investigation files*

- This series consists of BC Ambulance Service (BCAS) and air evacuation major accident and incident investigation files between 1992 and 2011.

- GR-4041 Witness statements from CPR train robbery

- These records purport to be related to a train holdup by the infamous Bill Miner at Ducks. The details match other historical accounts of the incident; however, the year is wrong! These may benefit from some further research.

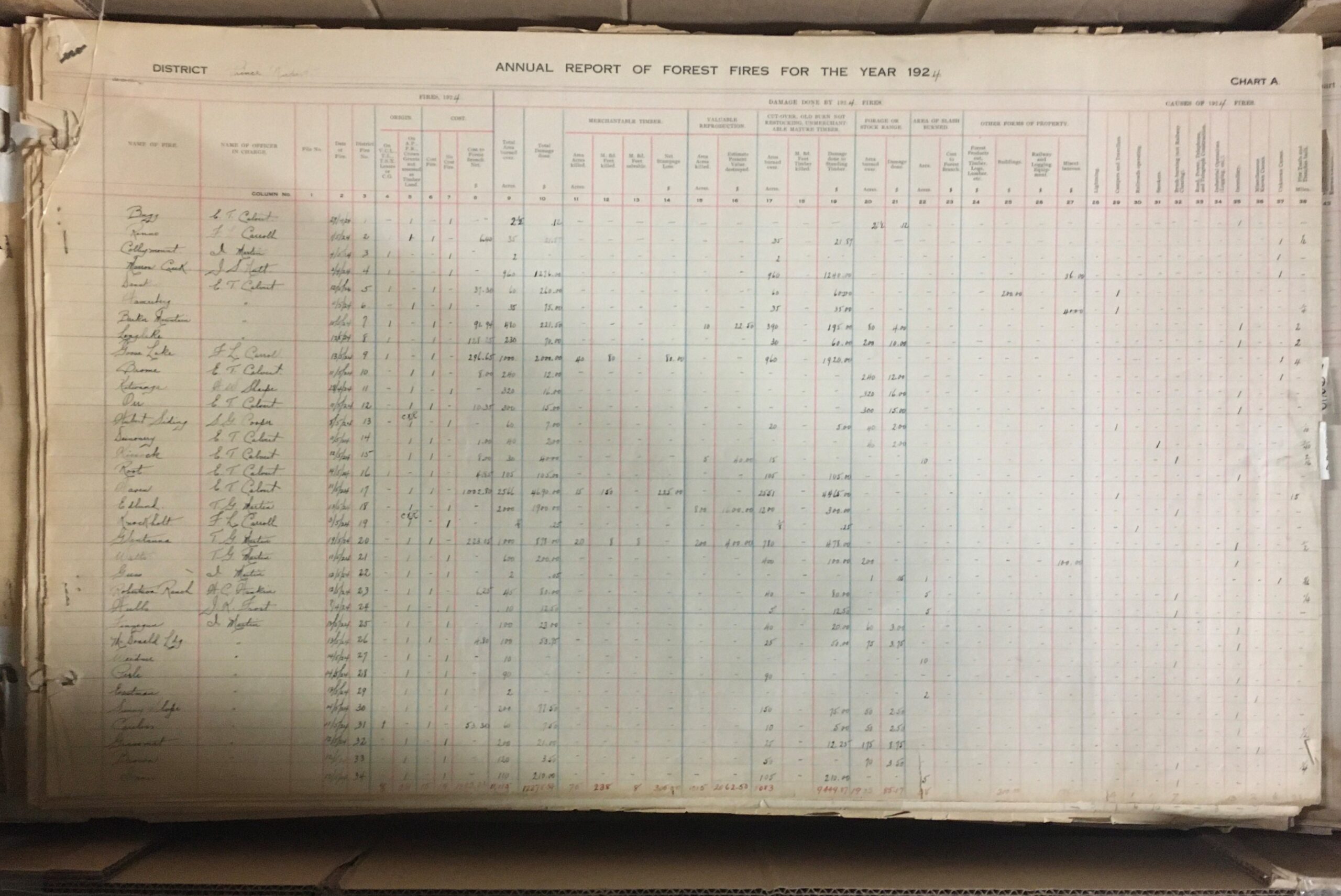

- GR-4048 Prince Rupert Forest District wild fire mapping records

- These huge volumes document wildfires in the Prince Rupert region from 1921 to 1980

- GR-4051 British Columbia Lottery Corporation’s ombudsperson’s investigations*

- This series consists of the ombudsperson’s investigation into the British Columbia Lottery Corporation’s prize payout procedures between 1999 and 2010. BCLC retailers and BCLC retailer employees appeared to be winning major prizes at a higher rate than other players in the province. The public and the media expressed concern that some of those winning tickets may actually belong to ordinary players.

- GR-4063 Cariboo government office records

- This series contains colonial records from the Cariboo region, including Barkerville. Records cover all aspects of government administration in the area from registering mining claims to court cases to crime statistics.

- GR-4064 Correspondence regarding immigration

- This series includes correspondence of the Provincial Immigration Officer from 1903-1905. Many records relate to the deportation of Japanese people under the racist 1904 Immigration Act.

- 24930E Plan of the No. 2 Extension coal mine

- This plan was made as part of the investigation into the cause of a 1909 explosion in the Ladysmith mine, resulting in the deaths of 32 men.

- GR-0522 Kamloops Government Agent land records

- This is a large series of records (160 boxes) that show a comprehensive history of land use in the Kamloops area over 100 years. This includes the time period the land was managed by the Canadian government as part of the Railway Belt.

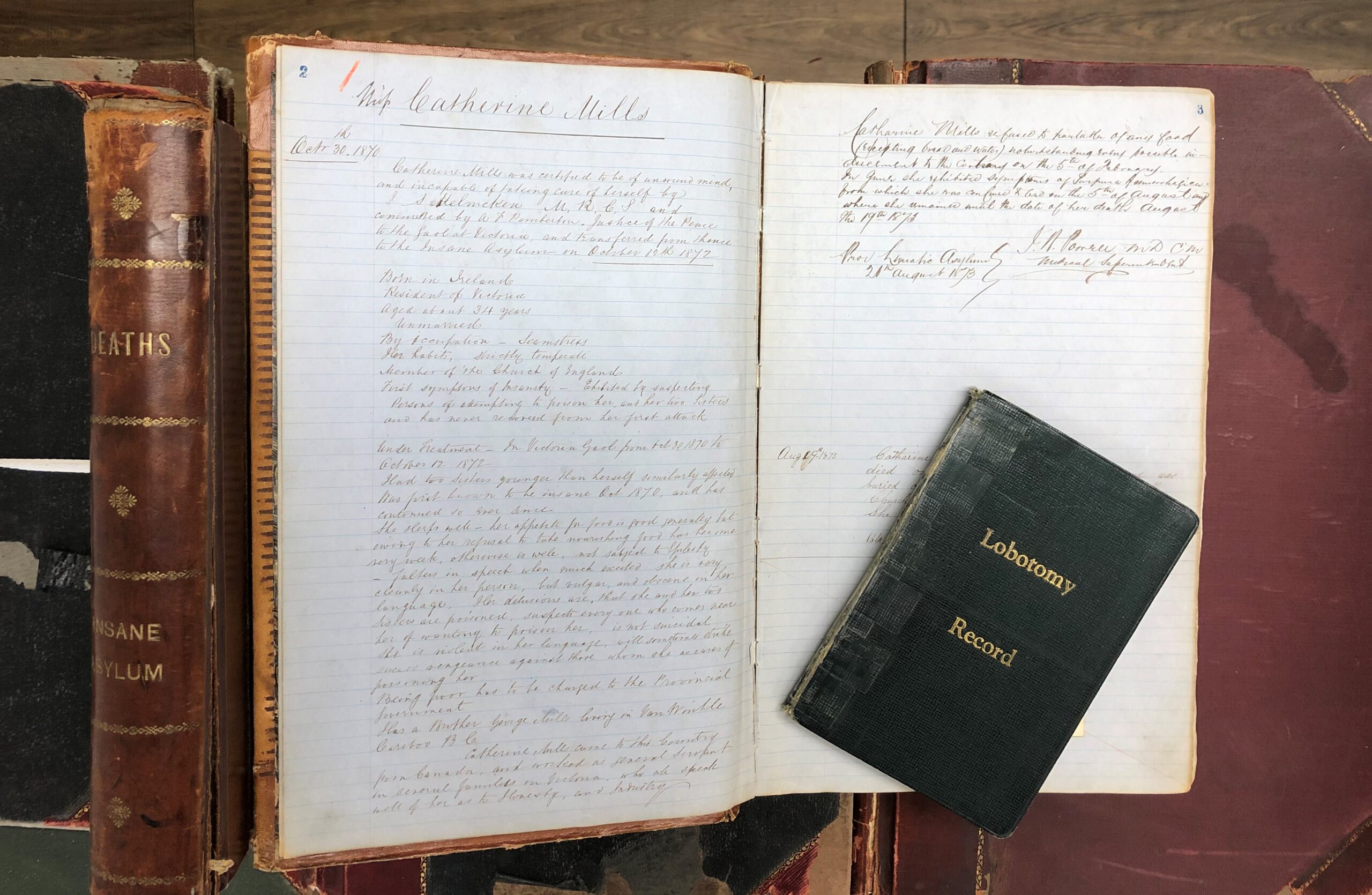

- GR-3929 Riverview Hospital Historical Collection*

- This collection includes a wide variety of records related to the operation of Riverview Mental Hospital (previously known as Essondale). The records were collected and maintained by the Riverview Historical Society. With the closure of the hospital in 2012, government records in the society’s holdings were transferred back to the government and have recently been made available in the archives. The collection includes records of all media and provides an overview of the hospital’s history, grounds, staff, and patient care.

- BC Place Stadium

- Canada Place – the cruise ship terminal

- Skytrain

- Redevelopment of False Creek – the Expo 86 site

Every year the Government Records team at the BC Archives processes over 2,000 boxes of records created by the provincial government. Most of these records can now be accessed by anyone, even you! Just remember that all government records are covered by privacy legislation, such as the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act. This means some records have access restrictions on sensitive or personal information. Here is an overview of just a few of the record series from the last year or so that are now available in our database.

A page from the GR-4064 fire atlas. Each volume measures over three feet by four feet and weighed over 60 pounds.

A page from the GR-4064 fire atlas. Each volume measures over three feet by four feet and weighed over 60 pounds.

A selection of volumes from GR-3929, including the first patient file from 1870.

A selection of volumes from GR-3929, including the first patient file from 1870.

Bonus records! Here are some other records that were made available a bit before 2021, but are still worthy of a mention:

*These series include sensitive personal information or other restricted records that are not publicly accessible.

A public notice to be posted in schools, included with police records in GR-4000

A public notice to be posted in schools, included with police records in GR-4000

Government is constantly evolving to meet the needs of the citizens it serves. This often results in the renaming and reorganizing of its various branches and departments. These changes can make it tricky to track which government body was responsible for creating and maintaining particular records through the years. To help myself better understand who created some of the land records I was working with, I set out to create a visual representation of how the land management functions of government moved around over time. This soon expanded to include several other ministries whose records I worked on. It eventually grew to cover all ministries (and their precursor departments) from 1871, when the province was created, to 2021.

Please see BC Government Ministry History Diagram for the most current version of the diagram.

I created the chart using information from BC Archives authority records, Orders-in-Council and lists of Cabinet Appointments from the Legislative Library. Ministries are shown in square bubbles and are connected to each other with arrows. The oldest departments are at the top, moving down to the current ministries at the bottom of the page. The ministries are arranged in columns that represent broad categories of government functions, such as health or agriculture.

Arrows with solid lines show that a ministry was renamed. This usually means it continued to do pretty much the same work and fulfill the same functions of its predecessor.

Arrows with dotted lines show that some functions moved to another ministry. Dotted lines also show links from ministries that are established (created) and disestablished. I was only able to note large changes; sometimes the various branches that make up a ministry were split between a half dozen other ministries, making it pretty impossible to track all their movements individually.

The complexity and change over time make this a bit overwhelming to look at all together. But the changing names of a ministry can provide a high-level snapshot of general trends in government’s priorities over time. Each ministry is usually focused on a single function or issue, such as providing health care or managing public forests. The evolution of ministries reflects what government thought was important—and what mattered to voters. To a certain extent, this also reflects what mattered to society at large, though government was dominated by white men for most of the province’s existence, and universal enfranchisement did not occur until 1952.

Government departments changed very little from the province’s creation in 1871 until the 1970s. Government was small. Initially, the Attorney-General and Provincial Secretary were responsible for functions that would be divided among a dozen different ministers today. The major changes involved the creation of new departments as the role of government began to expand in the twentieth century.

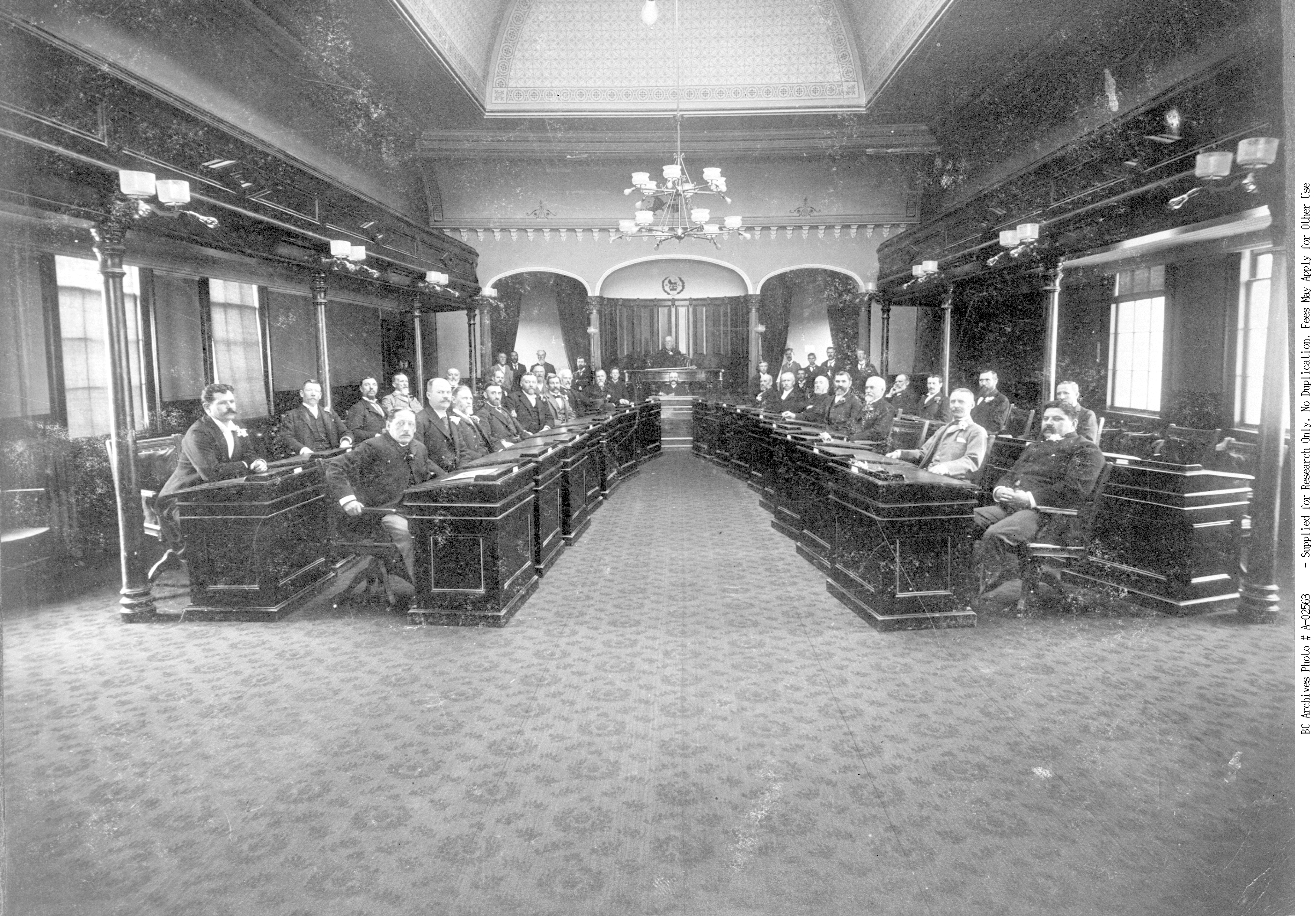

Members of the Legislative Assembly demonstrating some pretty good social distancing. Photo taken in 1870 in front of the Victoria government buildings known as the Birdcages, after the union of the two colonies and just prior to Confederation. C-06178.

Initially, building infrastructure and promoting the industrial harvest of natural resources (to expand economic opportunities for other white settlers) appears to be more of a priority than providing social supports. For example, two separate departments for railways and public works were established almost 50 years before the Department of Health Services and Department of Social Welfare were finally created in 1959.

In 1976, all departments were renamed and became ministries. After this point, changes became much more common. By the 1990s it seems to have become fairly standard practice for a newly elected government to reorganize Cabinet, appointing new ministers to differentiate themselves from the previous government and reflect changing priorities throughout their term in office.

Some ministries have remained remarkably similar over the last hundred years. Others have been regularly broken up, combined and moved around in ways that, at times, can seem confusing and a bit counterintuitive. For example, in 1978, the Ministry of Recreation and Conservation was disestablished and broken into several ministries, including a new Ministry of Deregulation.

BC Legislative Assembly, Seventh Parliament, Third Session, in 1897 in the Birdcages. Construction of the current Legislative Assembly building was completed the following year. A-02563.

Names have power. Word choice can really impact how people perceive things, and the level of importance or value they place on an issue. The arm of government responsible for social services provides a good example of this. It has fulfilled fairly similar functions over time, but the language around the work has evolved alongside societal beliefs about poverty. It began in 1959 as the Department of Social Welfare. Later names included the Department of Rehabilitation and Social Improvement, the Ministry of Human Resources and the Ministry of Employment and Income Assistance. Currently, it is the Ministry of Social Development and Poverty Reduction.

Establishing (or disestablishing) a ministry shows that government is assigning its affairs a certain level of importance, with an elected official appointed to focus on the function or issue. The creation of a Ministry of Women’s Equality in 1991, when BC’s first female premier Rita Johnson was in power, shows women’s equality was an important issue for government at the time. In 2001, this ministry was disestablished and lumped into the Ministry of Community, Aboriginal and Women’s Services with four other disestablished ministries, including the also-disestablished Ministry of Aboriginal Affairs.

Overall, I have found the chart a helpful way to track government’s changing responsibilities at a glance. My hope is that it can be a useful tool for researching archival government records. A record’s creator (often the ministry or department that created it) is one of the main things archivists look at when arranging and determining different series of government records (GR-numbers) in the BC Archives database. If you can think about the ministry that may have created the records you are looking for, it may provide access to some unexpected results. You can search for archival records by creator here.

Happy researching!

As a government records archivist, I process a lot of records related to land or resource use, and specifically forestry records. Since the beginning of British Columbia’s colonization, forestry has been a major part of the province’s economy. After over 150 years of industrial logging, the majority of the province has been disturbed by some kind of industrial activity, leaving an estimated 2.7% as productive old growth forest today.

Most land in the province is Crown land controlled by the provincial government. Crown land and resources—in this case timber—are leased or licensed to forestry companies to use. These agreements are generally referred to as timber tenures and can include a variety of uses, lengths of time they are valid for and other required management practices.

Managing all these resources has created a huge amount of government records. Many of these are now kept by the BC Archives for government reference and historical knowledge, and so that the public can hold its government accountable. I recently processed a series of records related to forestry in the Clayoquot Sound area, now part of GR-3659.

GR-3659 documents a type of timber tenure referred to as a Tree Farm Licence (TFL). Most of western Vancouver Island is covered by a handful of TFLs. TFLs provide a forestry company with almost exclusive rights to harvest timber and manage forest in a certain area for 25 years. Every 5 years, companies are required to create detailed plans outlining how they will manage the land and resources within the TFL area.

Working with the records in GR-3659 got me thinking about a related historical event—the 1993 Clayoquot Sound protests, also known as the War in the Woods, which occurred primarily on TFL 54 and TFL 57. So, I took a look at some of the other records that document it.

Protests and blockades began in the 1980s after logging was proposed on Meares Island in Clayoquot Sound. Several attempts were made by the government to reach a consensus between the members of the forest industry, environmentalists, municipalities and Indigenous Peoples. These included the Clayoquot Sound Development Task Force (GR-3535, box 921203-0023) and the Clayoquot Sound Development Steering Committee. Environmentalists left the Steering Committee in 1991 after the government refused to defer logging until an agreement was made. The Steering Committee ultimately dissolved in October 1992, without completing a finalized development strategy.

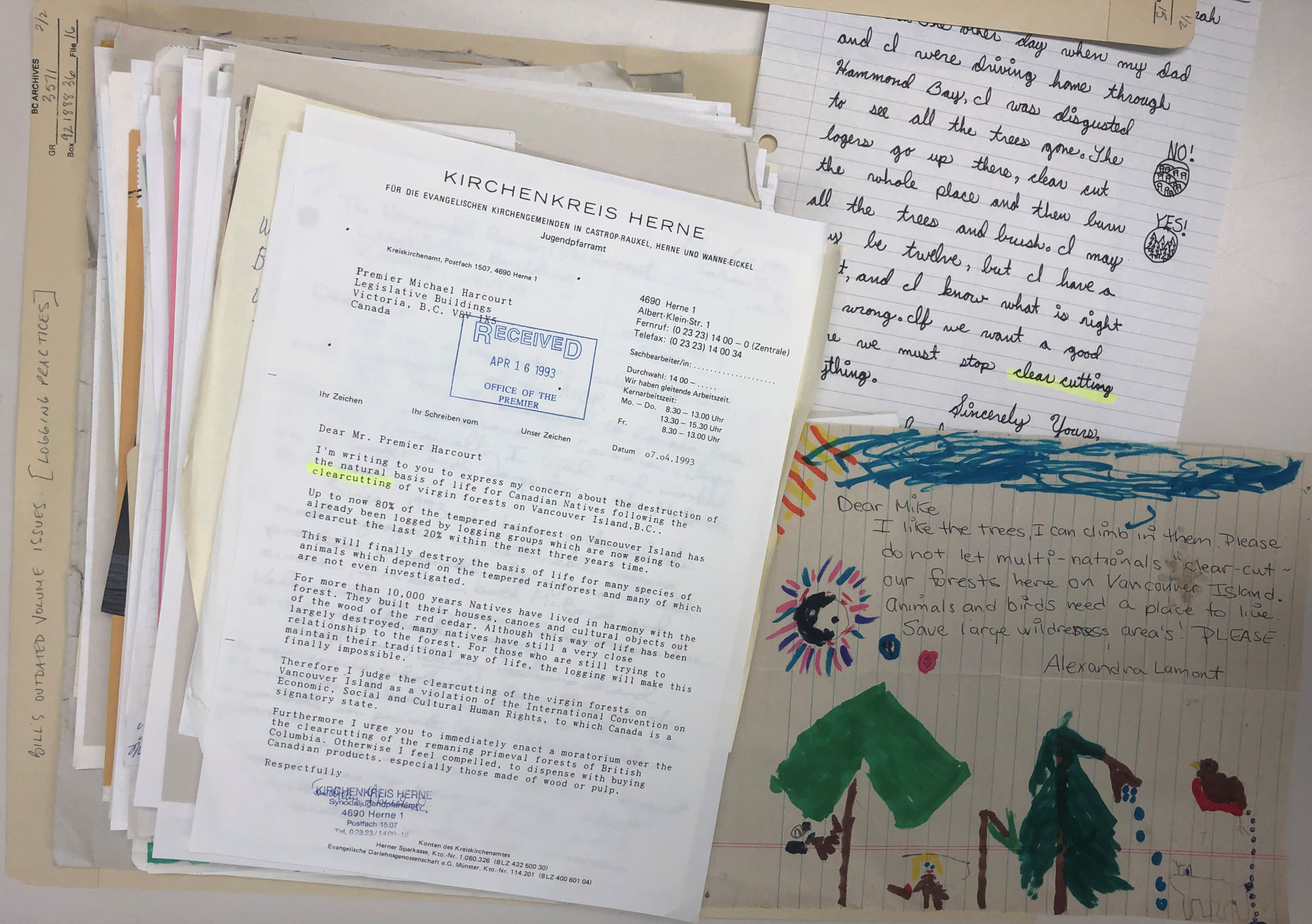

A few months later, in April 1993, Cabinet passed the Clayoquot Sound Land Use Plan, but it was widely contested. The government’s lack of consultation with local First Nations and the large area of old growth forest available for clear cutting resulted in protests that spread around the world. Protest camps and blockades were set up to prevent logging, in defiance of court injunctions. Police attempts to enforce the injunction led to over 800 arrests. Thousands of people protested over the summer of 1993, making it possibly the largest event of civil disobedience in Canadian history.

Ultimately, the government was able to reach a consensus with the Nuu-chah-nulth First Nation, whose traditional territory includes Clayoquot Sound, and new land use plans were developed. This also led to the creation of Iisaak, a new First Nations owned logging company operating in the area (some of their records are in GR-3659), and the designation of Clayoquot Sound as a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve.

Letters protesting old growth logging received by the Premier in 1993 from across Canada and the rest of the world (BC Archives, GR-3571, box 921888-0036, file 16)

A Tale for COVID Time

I have always believed that culture can transform, art can heal and history holds a mirror to ourselves and our time—thus my deep love for the study of history, arts and culture.

This current unsettling time of global pandemic crisis easily evokes feelings of insecurity and fear. It is a time of racism and uprisings against racism and other forms of discrimination. When I was given a small public space to share my work, I wondered what would be helpful when facing the challenges of our time.

The Royal BC Museum’s special Pocket Gallery A Tale of Two Families: Generations of Intercultural Communities and Family Lessons conveys a special message for the time of COVID. It assures us other people have not only made it through harsh times but have built legacies of success and community support.

Due to historical exclusion and colonial record-keeping practices, few families from settler minority groups can trace their histories back to the gold rush period that began in 1858. Since 2016, I have worked with two families that can: one French Canadian and the other Chinese Canadian. Their stories reveal rarely recorded generational continuities from the gold rush era to the present day. These families have survived times of great adversity, including the Great Depression and the Chinese exclusion era, to build lasting legacies in BC. What has kept the two families going for generations and through difficulties? What has allowed them to continue to grow and prosper today?

A deeper look at the family histories through the family members’ lenses reveals patterns in how the two families persisted through generations. Both families emphasize education, intercultural community building and kindness as family values. Their ideals resonate with our shared experiences and collective values as Canadians. During times of extraordinary challenges, such core values can shape people’s response. The stories of the Guichon and Louie families exemplify resilience through hard times in British Columbia history. Their family lessons are British Columbians’ strength.

On September 23, 2020, the museum hosted a special COVID-safe appreciation event for the featured families and communities of this Pocket Gallery. Maurice Guibord, président, Société historique francophone de la Colombie-Britannique, shared on video the significance of the Guichon family history.

Ms. Hilde Rose, the only living third-generation ranch operator, spoke on behalf of the Guichon family. With her husband Guy Rose, who was a third-generation Guichon, she operated the Quilchena Cattle Co. and the historic Quilchena Hotel for decades.

Mr. Alan Lowe, board chair of the Victoria Chinatown Museum Society and long-time beloved leader and former mayor of Victoria, spoke on behalf of the Victoria Chinatown communities to stress the importance of Chinatown history and the need to preserve it with a new museum in Victoria’s Chinatown.

Mr. Brandt Louie spoke on behalf of the Louie-Seto family as a direct descendant of the pioneer families of the Louies, Setos and Lees in BC, and of the Lews from the United States. He is also the third-generation leader of the H.Y. Louie Family Co. Ltd. His full speech can be found here.

The families’s joined commitment to education, intercultural community building and kindness resonate with our shared values as Canadians. These core values can help us shape our response during COVID time and the fight against discrimination through intercultural understanding and the pursuit of social justice.

Nature during COVID post

Royal BC Museum Biodiversity Research During the Pandemic

Nature is unrelenting. The zoonotic origin of the SARS-CoV-2 novel virus responsible for COVID-19 is a powerful reminder of the connections between human activities, health and biodiversity. As I write this, the COVID-19 pandemic continues to impact all aspects of human society, while the urgency to document, understand and protect biodiversity remains unabated. Museums in particular face the dual challenges of keeping the public engaged and maintaining their research programs. In many institutions, fieldwork, normally a major component of research activities during the summer months, has had to be postponed. Many aspects of learning, public engagement and curation of collections have moved online.

Researchers at the Royal BC Museum are considering the direct and indirect consequences of the pandemic on biodiversity while continuing to meet the challenges of biodiversity research. Aside from anecdotal reports (indicating, for example, that in many places biodiversity may be benefitting from reduced human activity), it is too early to provide a definitive answer to how the pandemic is affecting biodiversity. Given time, and with ongoing communication among scientists in natural history collections and the wider scientific community, this question can be answered by mobilizing and using biodiversity data found in natural history collections.

Ongoing communication of natural history collections is important, especially during this challenging time. Many people experience natural history collections only as museum exhibits. In this context, it can be difficult to visualize museum collections as baseline biodiversity data that are fundamental to diverse scientific fields. However, natural history specimens constitute the data for documenting biodiversity and constructing phylogenies, and they address evolutionary, ecological and biogeographic questions. Additionally, possibilities extend beyond the physical specimen, and may include genomic, behavioural and occurrence data. Therefore it is crucial that collections be maintained, that they grow, and that their data be continually enriched and shared. Through collections, we can improve our understanding of evolving species interactions, including those of pathogens and their hosts, which can help to better predict the risks of novel zoonotic diseases.

What about fieldwork? To cope with the travel restrictions and safety conditions surrounding the pandemic, some researchers have adopted different strategies. For example, in place of large-scale, rapid, people-intensive biodiversity surveys, some locations are studied in great detail over time, with fewer people. One project is the Quadra BioMarathon, conducted by researchers from the Hakai Institute to assess the diversity, abundance and composition of plankton just offshore from Hakai’s Quadra Island facility. The Royal BC Museum provides taxonomic expertise and advises on collection, preservation and identification of specimens.

Curators, collection managers and other researchers at the Royal BC Museum continue to work on collections, expanding, refining and making accessible the data through online collaborations with colleagues from as close as across town or as far as halfway across the globe. We are also committed to making biodiversity data and knowledge accessible to our diverse communities online.

Ongoing projects by Royal BC Museum researchers include taxonomic analysis, linking specimens to nucleotide, genome or protein data, and making data accessible through the Royal BC Museum online database.

Useful links:

GBIF Global Biodiversity Information Facility

iDigBio (Integrated Digitized Biocollections

Royal BC Museum Natural History Curators and Collection Managers

Dr. Victoria Arbour, Curator, Palaeontology

Dr. Henry Choong, Curator, Invertebrate Zoology

Dr. Joel Gibson, Curator, Entomology

Dr. Gavin Hanke, Curator, Vertebrate Zoology

Claudia Copley, Collections Manager and Researcher, Entomology

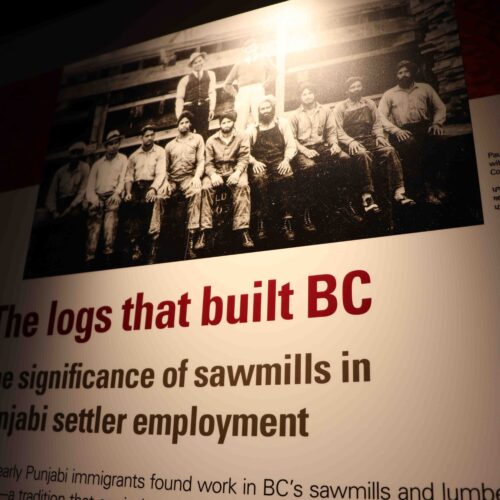

Heidi Gartner, Collections Manager and Researcher, Invertebrates

This article examines the Punjabi Canadian Legacy Project (PCLP), a partnership project between the Royal British Columbia Museum and the South Asian Studies Institute at the University of the Fraser Valley, as a case study of heritage from below. The project is based on community action research and practices, joining forces of memory, research, and community institutions, organisations, and groups. Considering ‘heritagisation’ as a process of heritage building, and drawing on their experience as practitioners on this project, the authors argue for the need to consider the vast diversities within and among communities, and the need to work on ‘heritagisation’ through ongoing dialogic engagement.

Through a myriad of continuous dialogues and inherent challenges, the process and progress of the PCLP is shaped by this dialogic engagement. As an ongoing project, the PCLP demonstrates how a network extended to diverse participants with shared goals can emerge through the organically developed heritagisation process encouraged by the partners’ collaborative efforts in an experimental model for community work by memory and research institutions.

See full article

Tom Bown, Volunteer Archaeology Research Associate.

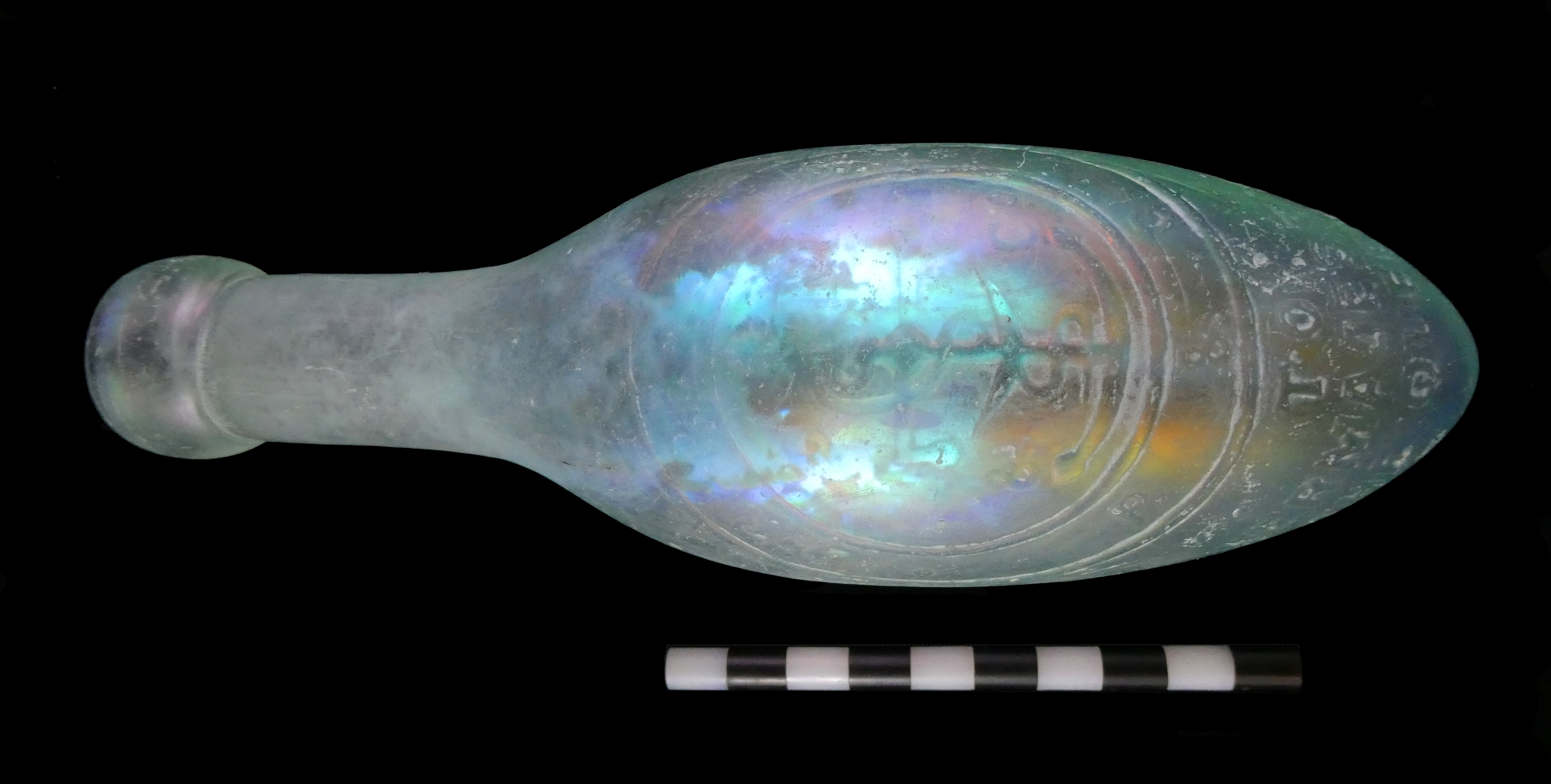

The first artifacts to arrive at the Royal British Columbia Museum from the Esquimalt Harbour Remediations dredging project (Esquimalt Harbour Remediation 2019) were a pair of pop or mineral water bottles from Charles Mumby, Portsmouth and Gosport.

This establishes a direct link between the Royal Navy Base in Portsmouth and Esquimalt.

As many of the Royal Navy ships would have been resupplied at Esquimalt, bottles and other artifacts from British Columbia companies will likely be found in Portsmouth.

Fig. 1 C. Mumby glass bottle from Esquimalt Harbour, DcRu-1278:125

(photo by author)

The first of these two bottles, is a short squat, amber coloured, cylindrical, bottle with a hand finished blob top. It is 15.5 cm. in height and 7.7 cm in diameter. Remarkably the cork is still in the neck and the bottle might still have the original contents. The front is embossed C. MUMBY & Co with a double circle embossed TRADE MARK P & G and a fouled anchor in the center. A bottle such as this would likely date between 1884 and 1910. Hannon and Hannon (1976) state the term trade mark on Mumby’s bottles post dates 1884.

Fig 2a C. Mumby “torpedo” bottle from Esquimalt Harbour DcRu-1278:36 (front). Photo by author

Fig 2b C. Mumby bottle from Esquimalt Harbour (reverse side). Photo by author

The second, is a “torpedo” shaped bottle also known as a Hamilt on style named after the inventor. In aqua coloured glass, it has a hand finished blob top. It is 19.0 cm in length and 6.1 cm at its widest diameter. On the front it has a double circle with TRADE MARK at the top and P&G at the bottom with the fouled anchor in the center the same as the one in figure 1. Above the circle only the last two letters are legible as ER the phrase was likely SODA WATER MAKERS and below the circle TO HER MAGESTY THE QUEEN. On one side it’s embossed C MUMBY & Co PORTSMOUTH AND GOSPORT on the opposite side. This bottle likely dates between 1884 and passing of Queen Victoria in 1901.

The torpedo style bottle was initially designed to withhold the pressure of the carbonation as well as keeping it from standing up right allowing the cork to dry and the carbonation to escape. They were used extensively in the mid 19th century and a few companies kept the design until the start of the 20th century. In British Columbia, there are no known bottlers that ordered torpedo style bottles embossed with company names.

Fig. 3 Colonel Charles Mumby. Photo with permission of David Moore, Historic Gosport

Starting on the mid-19th century, both the Royal Navy and British Army were recognizing alcohol as a serious problem. Lloyd and Coulter (1963:96) state: “Heavy drinking especially on shore, diminished towards the end of the century when tea and coffee were fast supplanting grog…” Increased levels of technology required higher levels of training that had little tolerance for drunkenness. In addition, the temperance moment was having an influence. As a result, many of the Royal Navy Clubs and regimental canteens were supplying their own soft drink bottles with club names and regimental crests (Bown 2015). A second advantage of these products was the carbonation which acted as a preservative keeping the contents for long sea voyages.

It would appear Charles Mumby saw an opportunity and was close at hand to supply the Royal Navy with a good supply of non-alcoholic beverages. Even his choice of logo with the fouled anchor was likely designed to appeal to the Navy.

Like many prominent businessmen in the Victoria era, Mumby was an officer in the local militia. This may have given him the necessary status and connections to supply the Royal Navy. The following was provided by David Moore at Historic Gosport (2019):

“Charles Mumby set up business in Gosport in 1849 as a chemist and manufacturer of mineral waters. His shop was at 47/48 High Street. His supply of water was a large bore hole in the yard at the back of the shop, which had rear access from North Street. At 345 feet he hit natural water in the chalk subsoil. He installed machinery to increase the production of natural ice. He produced famous soda water, ginger beer and lemonade, selling across the south of England. He supplied the Army and the Navy, receiving a Royal Warrant from Queen Victoria. The manufacture of mineral waters continued at his original premises in the High Street, and an office was opened up at Portsmouth, first at 71 St George’s Square, then, from the late 1870s, at 34 The Hard. Charles Mumby was a Poor Law Guardian, a magistrate, a County Councillor for Hampshire, and sat on innumerable public and social committees. Charles retired in 1885 leaving the business to his son Everitt.” It was floated as a company in 1898.”

WikiTree (2019) also states Mumby and Company was awarded a Royal Warrant to supply King Edward VII and the company continued to supply the Royal Navy until about 1970.

Fig. 4 A Photo of Mumby’s Shop, Photo with permission of David Moore, Historic Gosport

Located at 47/48 High Street sometime after the reign of Queen Victoria as the banner states TABLE WATER MAKERS TO HM THE KING. His business in Gosport was conveniently located within a kilometer of the Royal Navy base at Portsmouth across the harbour.

References

Bown, T. and C. Addams, 2015. Glass and Pottery of the Royal Navy and British Military: Historic and Archaeological Finds form the 18th, 19th and 20th Century. First Choice Books Victoria B.C.

Esquimalt Harbour Remediation 2019.

https://www.canada.ca/en/department-national-defence/news/2016/09/esquimalt-harbour-recapitalization-remediation-projects.html Accessed July, 2019.

Hannon T., and Hannon A., 1976. Bottles Found in St Thomas, Virgin Island Waters. Journal of the Virgin Islands Archaeology Society, Volume. 3, 1976, pp. 29-46.

Historic Gosport, 2019. David Moore Webmaster.

https://historicgosport.uk/bottles/ Accessed July, 2019.

Lloyd C., and Coulter J. L. S., 1963. Medicine and the Navy 1200-1900, Vol IV 1815-1900. E. & S. Livingstone Ltd. Edinburgh and London.

WikiTree 2019.

https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Category:Charles_Mumby_and_Company. Accessed July, 2019.

Historic Objects from the Esquimalt Remediation Dredging Project

by Tom Bown, Volunteer Associate in Archaeology

Haq & History post

Punjabi Canadian Legacy Project Community Event

Museums across the world are going through paradigm shifts – a shift that calls for a transition of power and authority, and a transition from exclusions to more holistic models of inclusion. The Royal BC Museum has been working towards such shift through community history projects based on community engagement.

In this type of community-based heritage work, the goal is to work closely with previously marginalized groups for exploring, preserving and sharing self-identified communities’ heritage defined in their terms. Our hope is to facilitate the sharing of the self-identified communities’ diverse stories and heritage in our galleries and beyond from community perspectives and in community voices.

The Punjabi Canadian Legacy Project (PCLP), a partnership project between the Royal BC Museum and the South Asian Studies Institute at the University of the Fraser Valley, is one of the museum’s attempts toward this goal. Six years ago in the summer of 2013, the initial discussion that eventually led to the creation of the PCLP took place in the Fraser Valley. Almost four years ago in 2015, the PCLP Advisory Committee met for the first time, where Mo Dhaliwal initiated a call for a revolution to break traditional institutional boundaries. It led to the community gallery intervention event. At this time, Punjabi Canadian communities took over the museum space and inserted their stories and presence.

Years later, community members gathered at the Royal BC Museum again on May 4, 2019, to view the cumulative result of the long-term work – the bilingual Pocket Gallery exhibit Haq & History: Punjabi Canadian Legacy Project a Quest for Community Voices, and the kiosk featuring community voices in the Logging area in the Modern History gallery. The kiosk was installed based on community feedback from the intervention event, sharing family, union and industry stories in the sawmill industry, an industry that have woven the Punjabi Canadian stories in BC together.

Leading this community gathering in the museum, Mo Dhaliwal, on behalf of the PCLP Advisory Committee, started with the land acknowledgement, and thanked all ancestors, matriarchs, and all living things for getting us to where we were. Ravi Kahlon, then Parliamentary Secretary for Sport and Multiculturalism, acknowledged all the PCLP advisors and community participants. The most moving part of the event was when people saw their stories and images, interwoven into the community stories under the five themes. The five themes were identified by the communities around the province as the most significant to Punjabi Canadian history in BC – trans-Pacific journeys, families and homes, community celebrations and commemorations, sawmill experiences and community activism for rights and justice.

This exhibit marked a historic moment for the underrepresented Punjabi Canadian stories in BC to be collectively preserved and shared. ‘Haq’ means rights, and the PCLP is about putting community voices and history in their rightful places. Next to the kiosk in the gallery, Mo ended the event by leading three calls of ‘Inquilab Zindabad!’ – ‘Long live the revolution!’ (in Punjabi) – calling for continuous work to move beyond traditional boundaries and create new paradigms for heritage work.

The Haq & History exhibit, pending funding, will later travel to the communities who helped shape this work.

Event Images:

The kiosk in the Logging area in the museum permanent gallery.

The Haq & History Pocket Gallery display

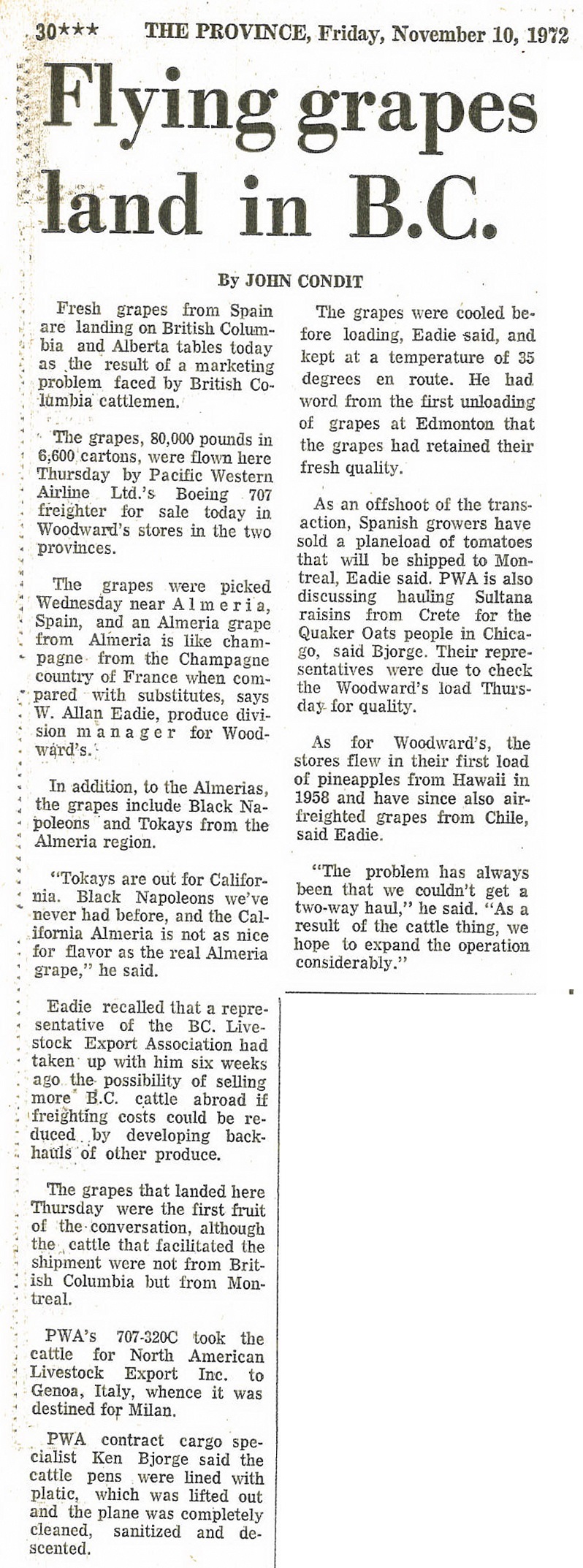

CETA 1972 style post

While working with archival documents it is always of interest to look at the other side of the page.

In today’s example, A person needed to publish several legal notices in the local paper.

Luckily, the entire newspaper page was submitted.

The following article appeared on the back of the page (The Province [Vancouver], Friday, 10 November, 1972.)

It describes how Pacific Western Airlines was able to ship live beef to Europe, because its cargo plane could return with a cargo of grapes which were now available throughout BC and Alberta.

The article also explains how the plane was cleaned, presumably before the grapes were loaded on to the plane.

The Wikipedia page for PWA mentions the following:

Boeing 707 equipment was added to the fleet in 1967… The addition of a cargo model Boeing 707 meant that livestock and perishables could now be carried all over the world, and the name Pacific Western became synonymous with “World Air Cargo”. The company aircraft visited more than 90 countries during this period of time.

Pacific Western operated a worldwide Boeing 707 cargo and passenger charter program until the last aircraft was sold in 1979.

This is in the era where container shipping was beginning its world wide adoption.

Air cargo was expanding during this time as well, when “Boeing launched the four engine 747, the first wide-body aircraft” in 1968.

As the newspaper report explains, transportation of people and goods only makes sense if the airplane is loaded to maximum capacity at all times.

This was the thinking behind the Triangular trading system of the 19th century.

Moving people extended this thinking to modern day hub airports such as Toronto Pearson, London Heathrow and Dubai UAE.

Even today with airplanes that can travel half way around the world, the take off and landing locations are the national hub airports.

Air cargo has undergone the same thinking.

In the 1972 news report, it only made sense to Pacific Western Airlines to undertake this one-off trip once the entire route was fully booked.

The article goes on to describe how the airline was looking for other opportunities. They recognized the potential, but the tipping point (the development of an airport hub for cargo) had not yet arrived.

To see what kind of completion PWA would face today simply go to an airplane tracking app and filter for FedEx planes, or track the Memphis airport.

UPS has a similar hub in Louisville. Here is an example of one airplane in the UPS fleet that revisits the hub city regularly. This particular plane left Louisville on 28 May 2017 and travelled around the world via Honolulu, Hong Kong, Dubai, Cologne, and Philadelphia, before returning to Louisville three days later.

When you read this article, there will probably be more recent examples of round the world trips or forays to Asia or Europe before returning to it’s home base.

The article does not quote anyone from the BC Livestock Export Association, however Europe is again front of mind for the Cattlemen’s Association.

Mr. W. Allan Eadie produce manager for Woodward’s, and PWA cargo specialist Ken Bjorge would be impressed!

As Mister Eadie says in the report, he hoped that this operation would expand because of “this cattle thing.”

He and Mister Bjorge may have failed to realize that the problem was not to solve the “cattle thing.” They needed to solve the “hub thing.”

On a side note, The Imax movie “Living in the Age of Airplanes” has an excellent section on the transportation of flowers that is well worth the price of admission.

PWA purchased CP Air to form Canadian Airlines International in 1987.

Canadian Airlines has the distinction of being the first airline in the world to have a website on the Internet (http://www.cdnair.ca/).

It merged with Air Canada in 2001.

Expo 86 opened its doors to the world on 02 May, 1986.

Leading up to the World Fair, several large infrastructure projects were proposed and planned for, so that they would be open and useable by the public by the time the fair opened.

These projects included

These projects were discussed on the Webster Show.

Of course politics was involved, as the mayor defended his vision of what Vancouver would look like, as it celebrated the hundredth anniversary of its founding.

Redevelopment of False Creek was a major issue – BC Architect Arthur Erickson and the director of planning for BC Place, David Padmore discuss the Expo 86 site plans.

Here is the interview of a member of the BC Place planning committee.

Sky train was a region wide issue.

This episode shows the proposed route of the LRT as Steve Wyatt drives the streets of Vancouver, trying to get as close to the proposed route as possible.

Bear in mind that the route used existing railway rights of way for the majority (if not all) of the line.

There are several versions of this. The final one was slowed down somewhat so you can see the surrounding city a little more easily.

For the unedited show see this Link.

Canada Place – the cruise ship terminal. Webster goes on a fly about/ walk about

BCTV was a major sponsor and broadcast daily from the Expo grounds.

Here is part of the hype, when some of the pieces get lost.

Counting Down to opening day

And after the exhibition

The auction

And distributing the wealth

I ran across an interesting video of describing how a Museum is using its food offerings to integrate them with the rest of the museum experience.

The item appeared as part of “CBS Sunday Morning” food edition on 20 Nov 2016.

Here is the link.

The menu recreates historically famous items from around the world as taught to the staff by the chefs who created them.

This is the link to the menu.

The menu includes the name of the chef, the restaurant, city, and year of creation.

Be sure to click through the Lounge, Dining Room and Beverage tabs!

One of the dishes created there is Oops! I dropped the lemon tart.

Three-Michelin-star chef Massimo Bottura’s describes how the dish was created here.

Feel free to research the chefs, restaurants and recipes listed on the menu. Time well spent!

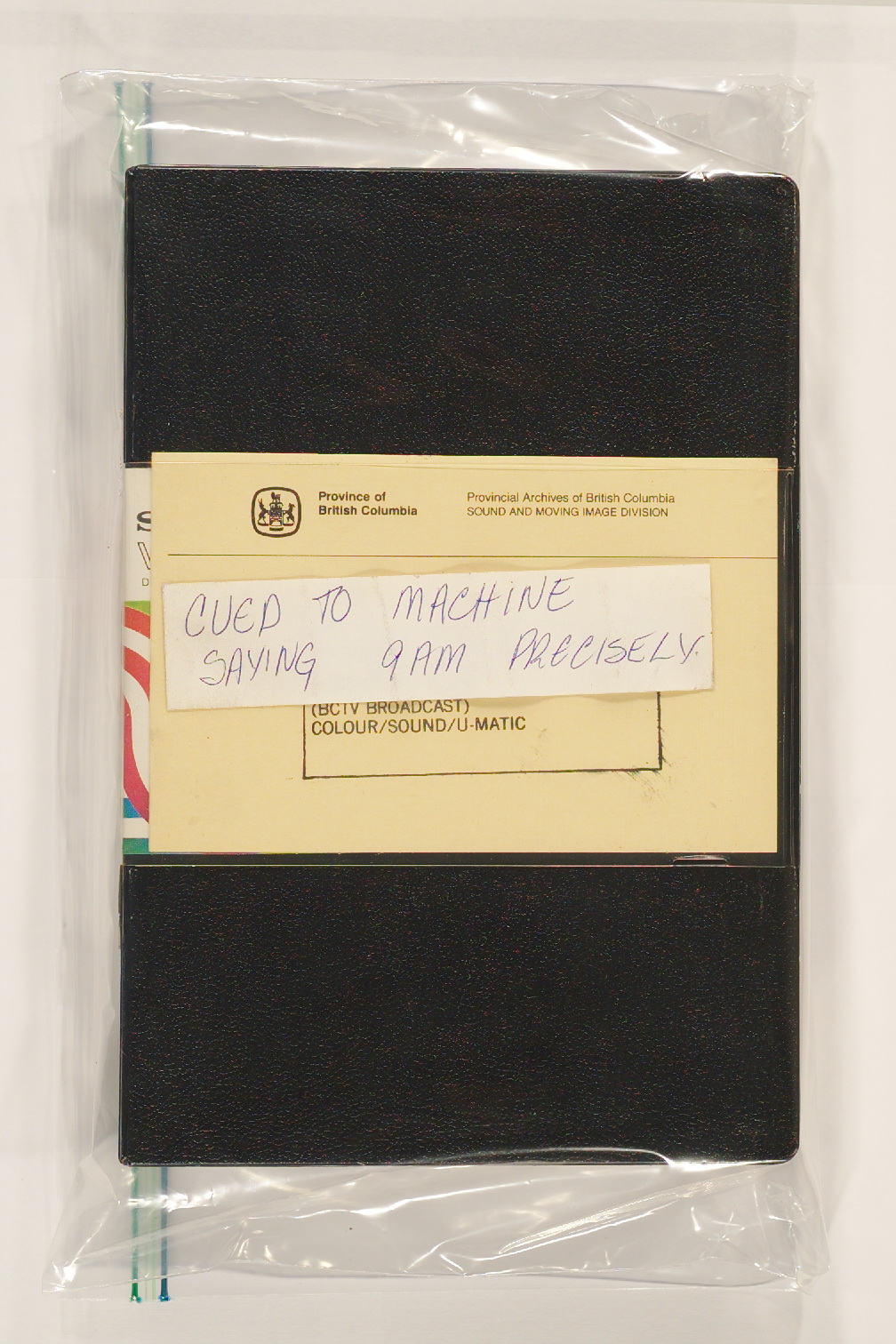

Nine AM Precisely post

Jack Webster was an icon of Vancouver and British Columbia News reporting.

His legacy includes video recordings of his entire Webster! show which aired on BCTV (CHAN – Channel 8) for nine seasons from 02 Oct 1978 through 03 Apr 1987.

Shortly after the last show aired, Jack Webster and BCTV* donated the videos for all his shows to the BC Archives.

The show originally aired from 9AM through 10:30AM on BCTV. For a period of years a half hour excerpt was rebroadcast on Victoria’s CHEK Channel Six at midnight.

The final regularly scheduled 90 minute show was broadcast on 27 Mar 1986. The last season of Webster! was reduced to one hour and moved to the 5PM broadcast slot.

Long before then the iconic phrase that Jack Webster used to announce upcoming shows was embedded into the cultural memory of BC’s news junkies.

The 1982 opening sequence emphasizes this by opening with an image of the Vancouver Block clock at 736 Granville Street set at “9AM precisely”.

Putting on the show.

Prior to each show a one hour U-matic tape began recording for the entire hour. It was swapped out at 10AM for a 30 minute tape. At the end of the show, they were labeled by the date and recording order. If special guests or events occurred during the show they were identified for possible future use.

One such note even used Webster’s famous phrase to identify the cue .

The Royal BC Museum is in the process of digitizing a large portion of these shows. Part of the process involves editing the original one hour and thirty minute videos and combining them into a cohesive whole.

No-one tended to the original recordings while the show was on the air. Because of this, the recording included the off air time as the commercials were airing. In most cases, sound engineers turned off the stage microphones. On occasion they were turned on for a brief time to check sound levels and the like. In other cases, upcoming video segments or title cards were cued up for use in future segments of the show.

The Royal BC Museum maintains digital master copies of the entire recordings as part of the Archiving process. Making these shows available to the public involves an editing process which removes the dead air time (where nothing is recorded on the original video) while ensuring that the on air portion, as well as the material recorded during the commercial breaks, is captured in its entirety.

One example that shows how helpful this can be is in the episode that ended the 1981-1982 broadcast season. The 02 Apr 1982 show begins with an hour long interview with Premier Bill Bennett. The final segment of the interview begins with Jack Webster smiling at something before he takes a telephone call for the premier. The off air recording shows what the cause of the smile was.

This was in preparation for the final part of the show which can be seen here.

Another example where knowing what happened off air is useful occurred during the lead up to Expo 86. As a corporate Sponsor, BCTV was closing each Webster! Show with a “Number of days to go” countdown. It appears the recording of the announcer used for this particular day’s segment was unavailable. This clip shows the preparation and result.

You can now watch an “ever expanding list” of Webster! episodes which includes “never before seen or heard” “behind the scenes” parts of the show. Simply visit the Royal BC Museum YouTube channel and click on the Webster! Playlist.

*Officially donated by Jack Webster Productions Ltd. and British Columbia Television Broadcasting System Ltd. – acquisition notes.