Archives, Access & Digital

- GR-3346.37 2021 Speech from the Throne

- The archives’ most recent record, created less than a year ago·

- GR-3518 Records of the Provincial Health Officer *

- This accrual covers the records of Dr. Perry Kendall, who served as the Provincial Health Officer from 1999 to 2018. The records address the health of Indigenous populations, water quality and pandemic influenza preparation among other public health topics.

- GR-3676 and GR-3677 Cabinet committee records and Premiers’ records*

- Large accruals were added to these series this year, documenting cabinet proceedings and priorities. Most records up to 1991 are publicly accessible.

- GR-3890 Drafting legislation case files*

- Comprehensive records covering all aspects of the process for drafting and approving provincial legislation. The records relate primarily to the 1970s and 1980s.

- GR-3948 Notebook related to the Tsilhqot’in War

- This delicate and difficult to decipher notebook relates to the events of the 1864 Tsilhqot’in War. It includes a diary of a group of settlers attempting to apprehend the Indigenous men allegedly involved in the deaths of several settlers.

- GR-3996 Conservation Officer Service major investigation case files*

- The series consists of the major investigation case files of the Conservation Officer Service between 1992 and 2007. Major cases are serious in nature and address complex issues such as trafficking animal parts, big-game poaching, illegal fishing or guiding, or selling animals for human consumption that are procured illegally.

- GR-3999 Environmental Appeal Board records*

- This series includes appeal files submitted to the Environmental Appeal Board and its predecessors: the Pollution Control Board and Pesticide Control Board. The records document the government’s management of the environment.

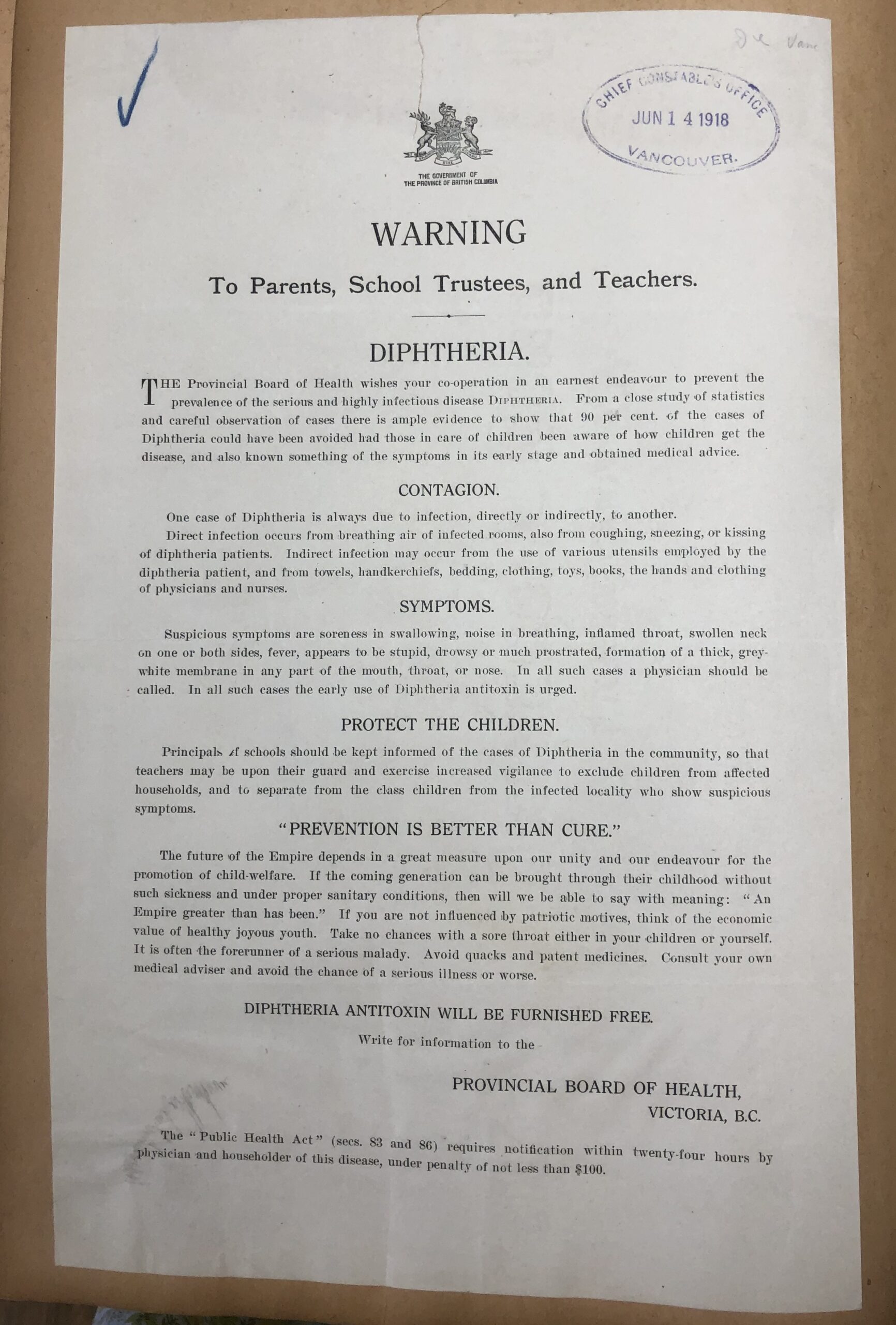

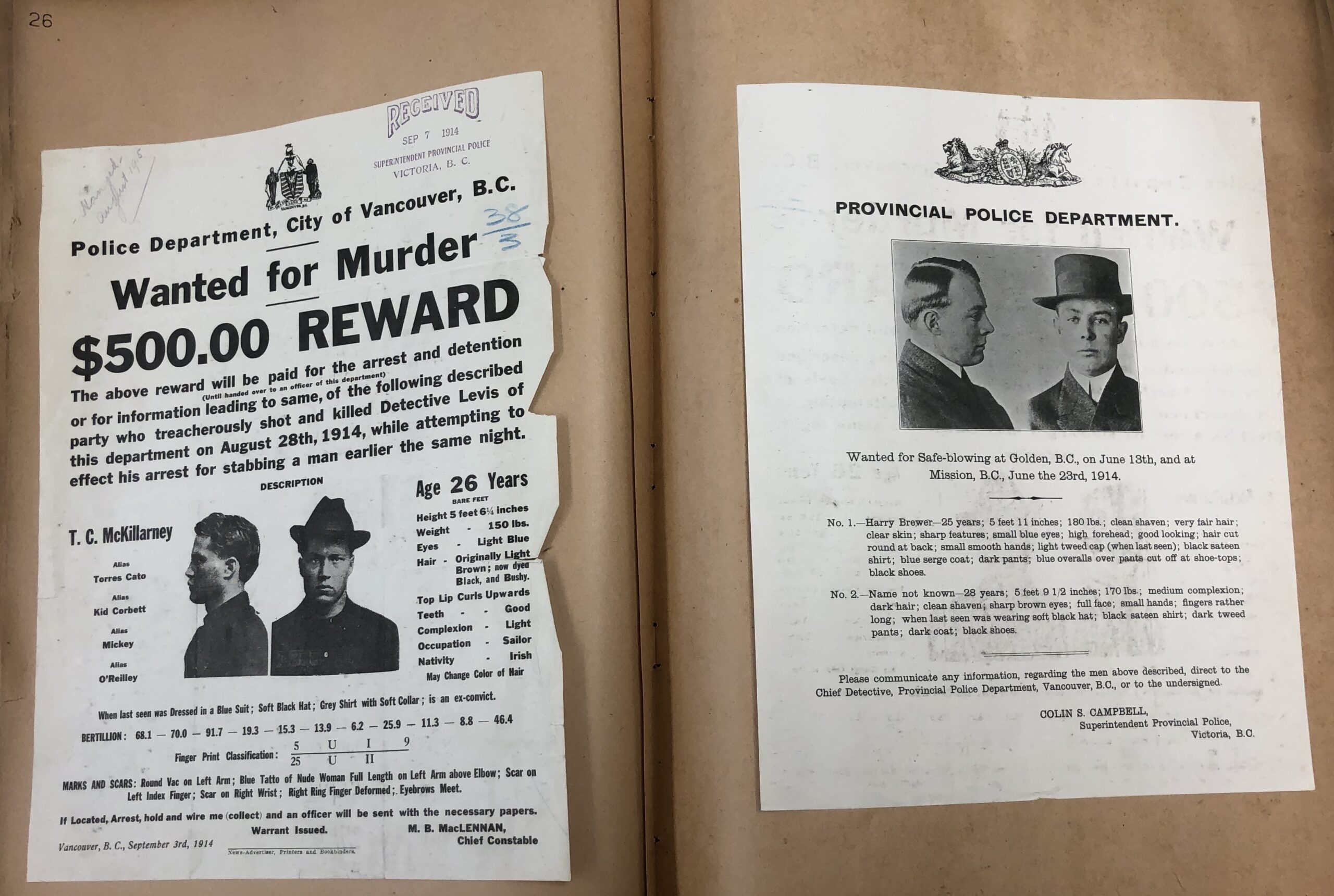

- GR-4000 Provincial Police circulars and wanted posters*

- This series includes a variety of informational posters for alleged criminals wanted across Canada and the United States. Many of the records are pasted into indexed volumes, serving as simple criminal record “databases.”

- GR-4002 Forest Practices Board meeting files*

- This series includes records of the Forest Practices Board which serves as the independent watchdog for sound forest and range practices in the province.

- GR-4005 Conservation Officer Service wildlife attack final reports*

- This series consists of final reports summarizing wildlife attacks on humans created by the Conservation Officer Service between 1991 and 2012. They illustrate the evolution of wildlife attack investigative technique, causes of wildlife attacks, and methods used to dispatch wildlife.

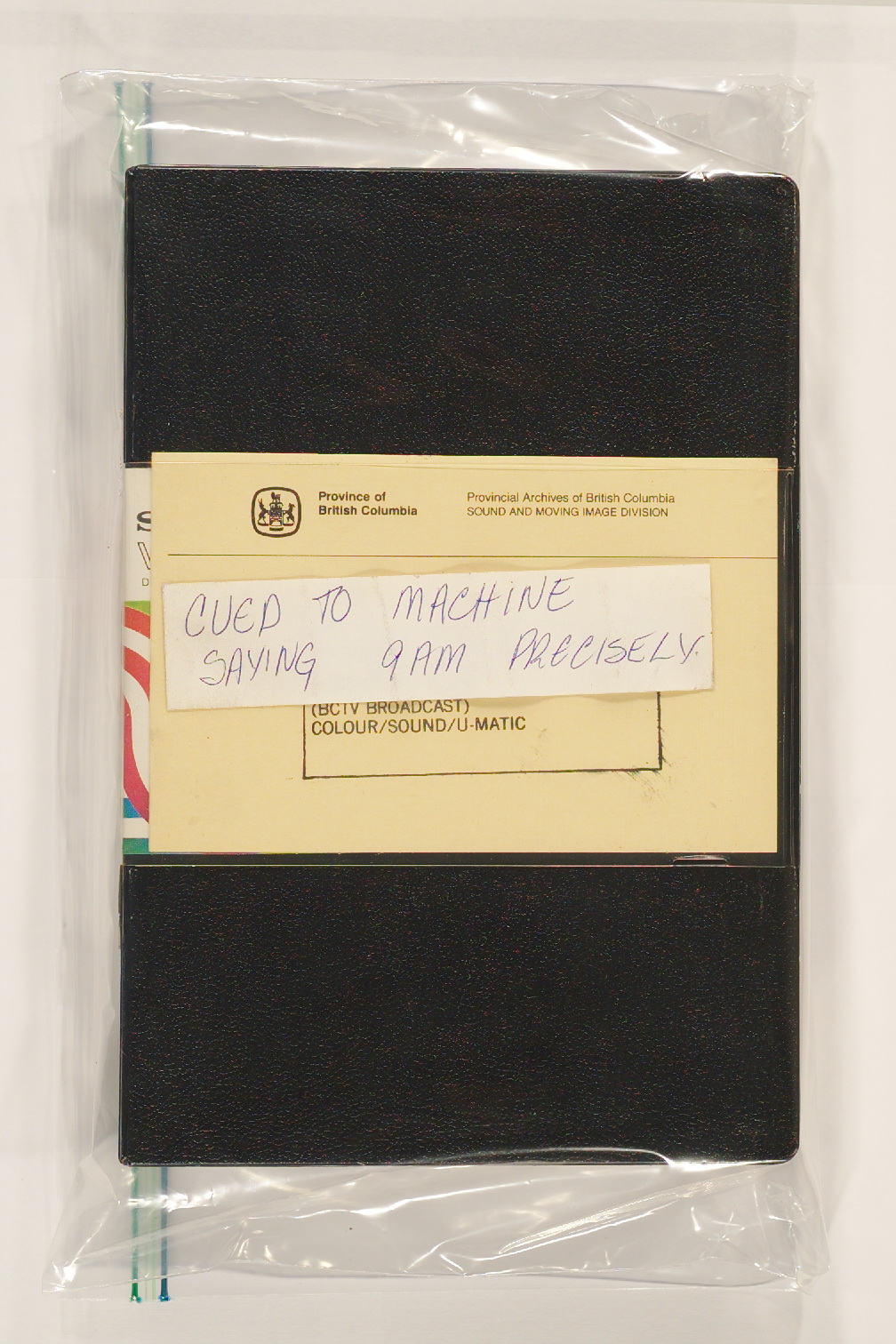

- GR-4008 BC Ambulance Service and air evacuation major accident and investigation files*

- This series consists of BC Ambulance Service (BCAS) and air evacuation major accident and incident investigation files between 1992 and 2011.

- GR-4041 Witness statements from CPR train robbery

- These records purport to be related to a train holdup by the infamous Bill Miner at Ducks. The details match other historical accounts of the incident; however, the year is wrong! These may benefit from some further research.

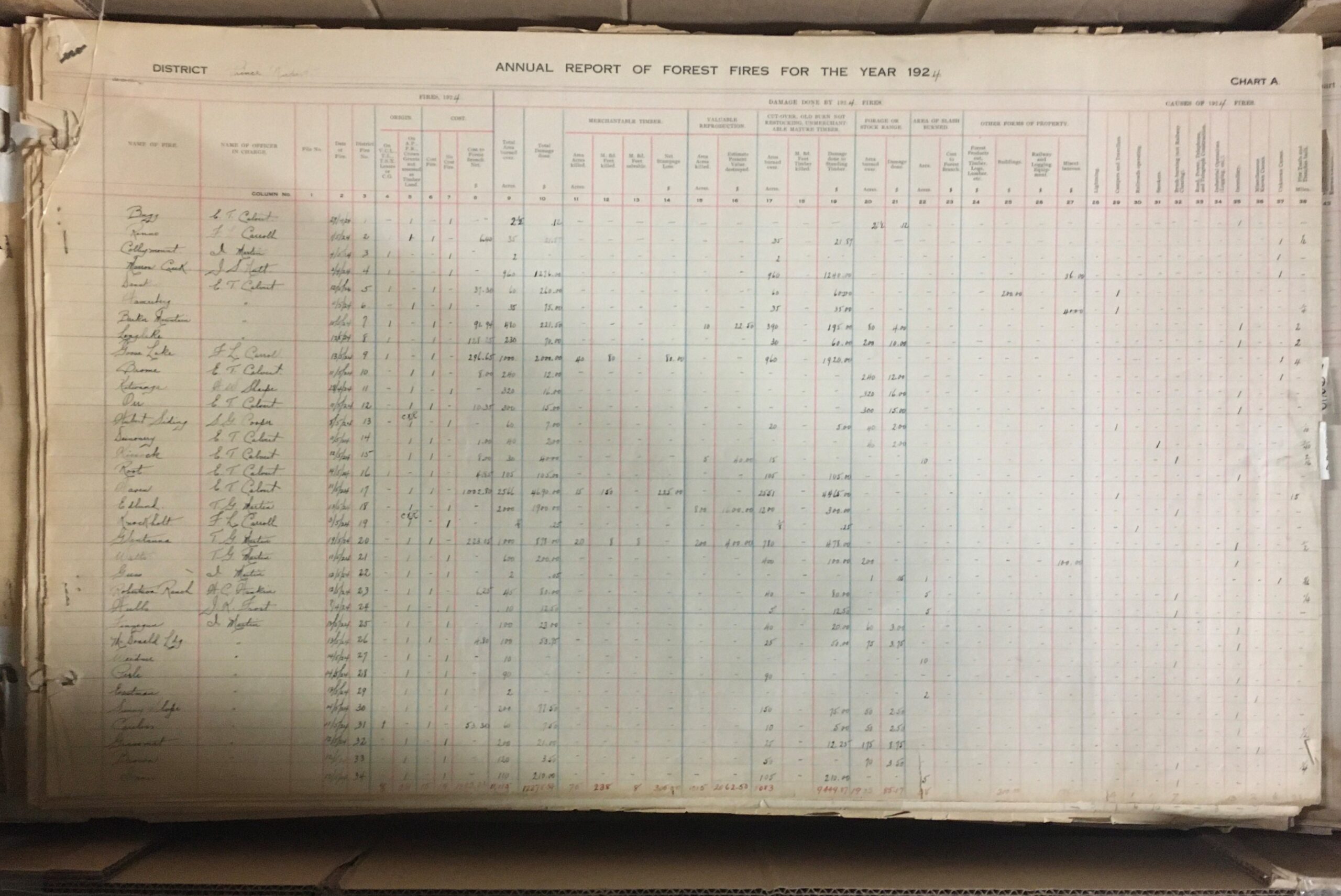

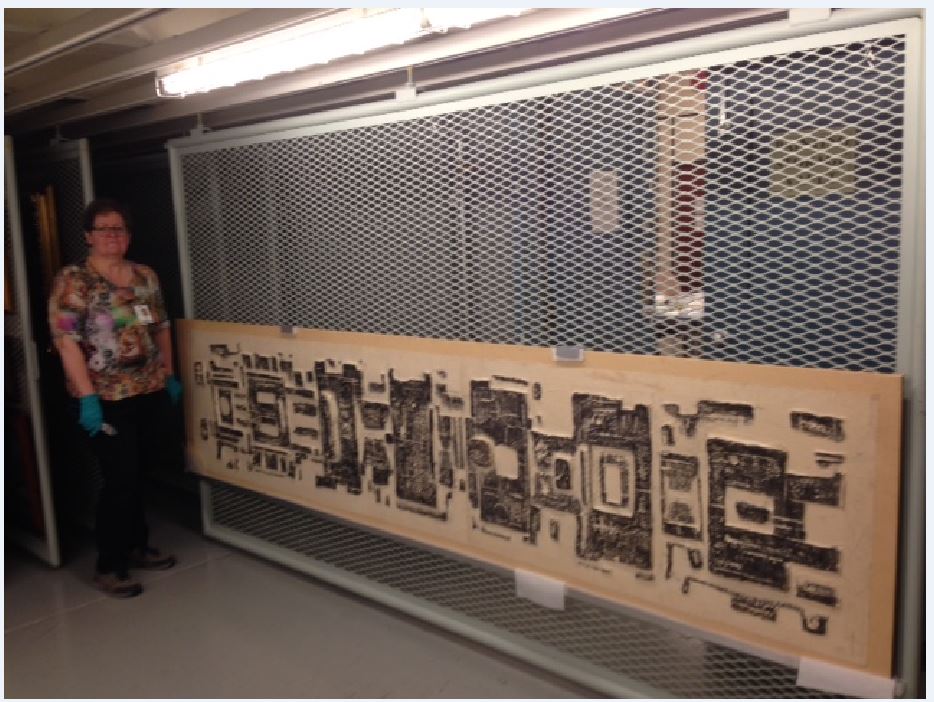

- GR-4048 Prince Rupert Forest District wild fire mapping records

- These huge volumes document wildfires in the Prince Rupert region from 1921 to 1980

- GR-4051 British Columbia Lottery Corporation’s ombudsperson’s investigations*

- This series consists of the ombudsperson’s investigation into the British Columbia Lottery Corporation’s prize payout procedures between 1999 and 2010. BCLC retailers and BCLC retailer employees appeared to be winning major prizes at a higher rate than other players in the province. The public and the media expressed concern that some of those winning tickets may actually belong to ordinary players.

- GR-4063 Cariboo government office records

- This series contains colonial records from the Cariboo region, including Barkerville. Records cover all aspects of government administration in the area from registering mining claims to court cases to crime statistics.

- GR-4064 Correspondence regarding immigration

- This series includes correspondence of the Provincial Immigration Officer from 1903-1905. Many records relate to the deportation of Japanese people under the racist 1904 Immigration Act.

- 24930E Plan of the No. 2 Extension coal mine

- This plan was made as part of the investigation into the cause of a 1909 explosion in the Ladysmith mine, resulting in the deaths of 32 men.

- GR-0522 Kamloops Government Agent land records

- This is a large series of records (160 boxes) that show a comprehensive history of land use in the Kamloops area over 100 years. This includes the time period the land was managed by the Canadian government as part of the Railway Belt.

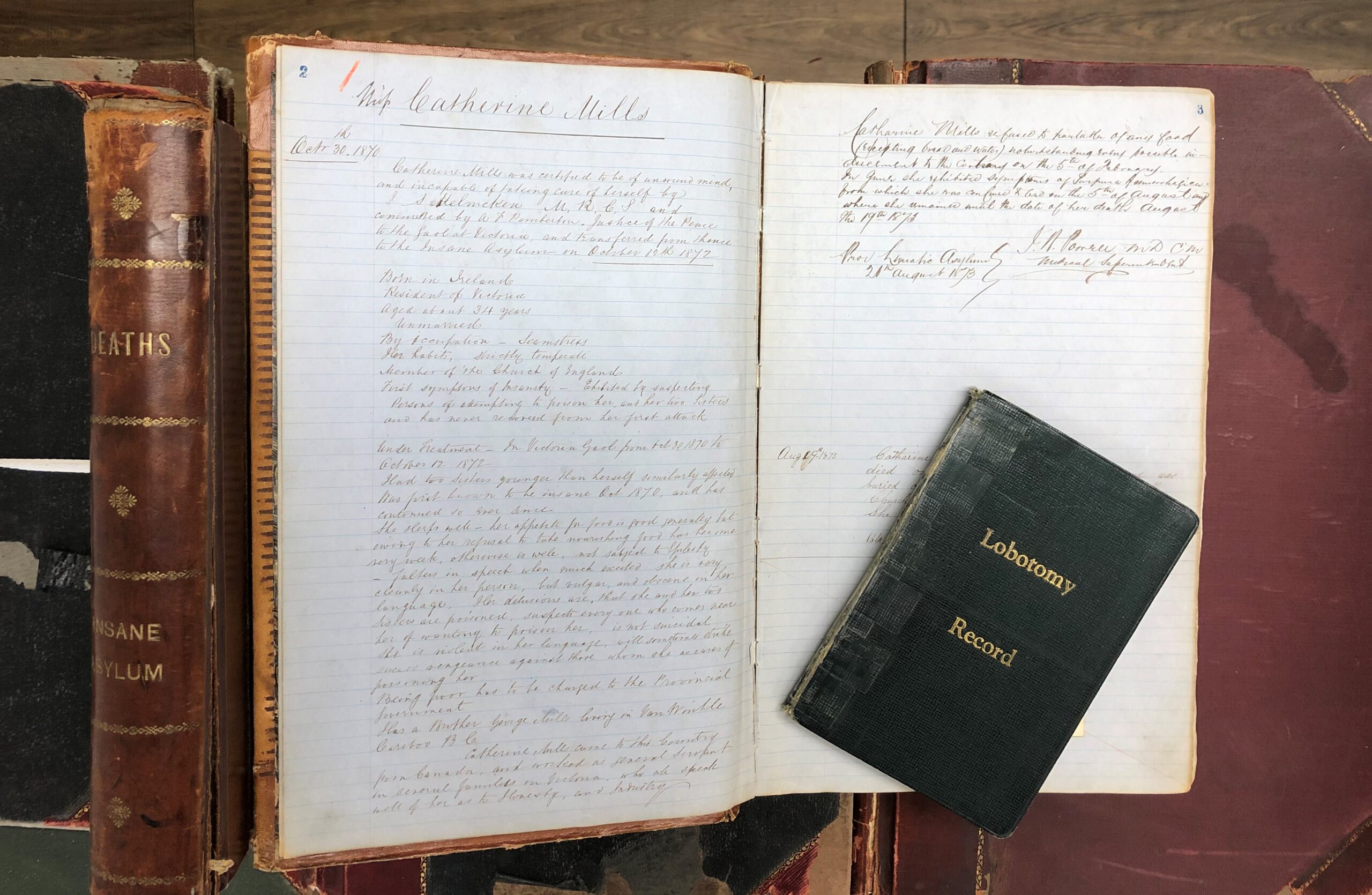

- GR-3929 Riverview Hospital Historical Collection*

- This collection includes a wide variety of records related to the operation of Riverview Mental Hospital (previously known as Essondale). The records were collected and maintained by the Riverview Historical Society. With the closure of the hospital in 2012, government records in the society’s holdings were transferred back to the government and have recently been made available in the archives. The collection includes records of all media and provides an overview of the hospital’s history, grounds, staff, and patient care.

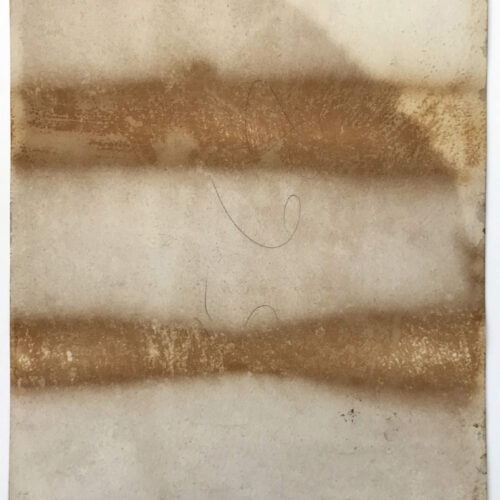

- A partial backing means that the painting is not supported evenly, which often leads to folds, creases and other types of damage if the work is not handled very carefully

- Differential support can also lead to deformations in the paper because some areas of the sheet are constricted from movement (with environmental fluctuations) and some aren’t, leading to a build-up of internal stresses

- The poor-quality cardboard was also very brittle and likely to crack or snap. If a snap in the cardboard were to happen, this would inevitably translate into bends, creases or even breaks in the painting as well.

- Acidic components of the poor quality wood pulp cardboard (as well as acidic components that appear to have been absorbed from another source, visible as brown lines across the cardboard backing) will leach into the painting causing the paper to degrade and become brittle and discoloured. This could eventually affect the paint as well.

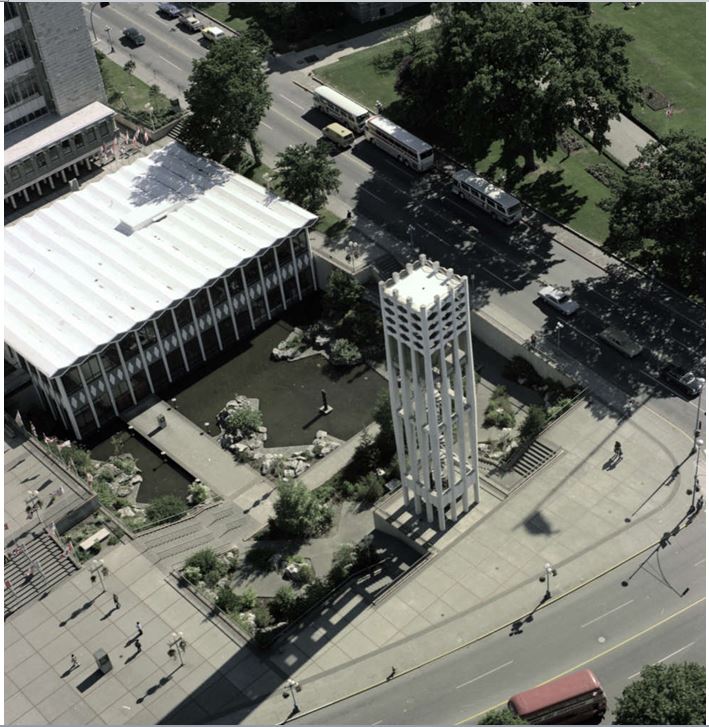

- BC Place Stadium

- Canada Place – the cruise ship terminal

- Skytrain

- Redevelopment of False Creek – the Expo 86 site

As the museum and archives prepare to move the collections to the new Collections and Research Building in Colwood, BC, more items are arriving in the Conservation labs for treatment to ensure they are stable enough to endure the journey. This past year, one portrait made its way to the paper conservation lab in need of pre-move stabilization. In this case, a large hole and obvious moisture damage were cause for concern.

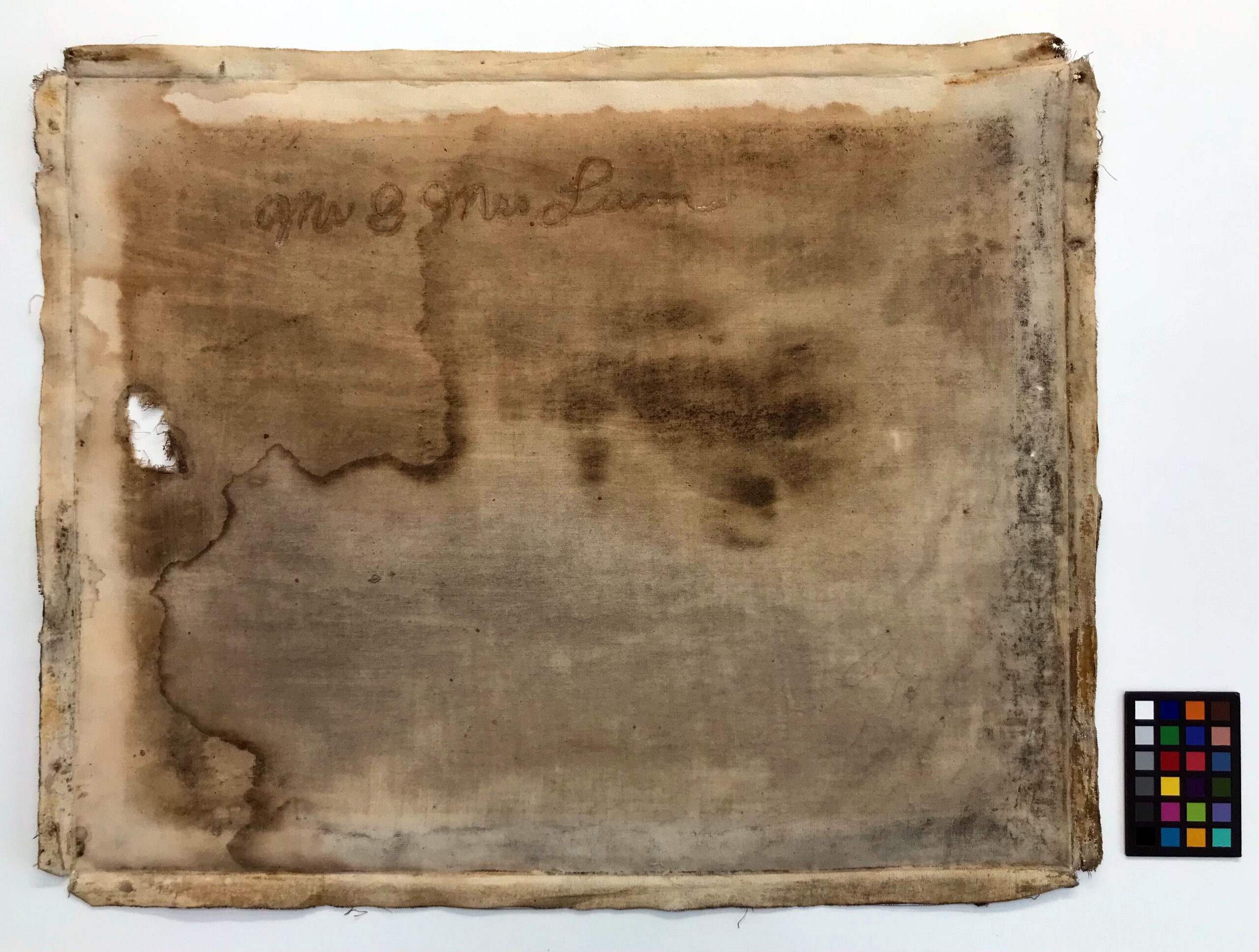

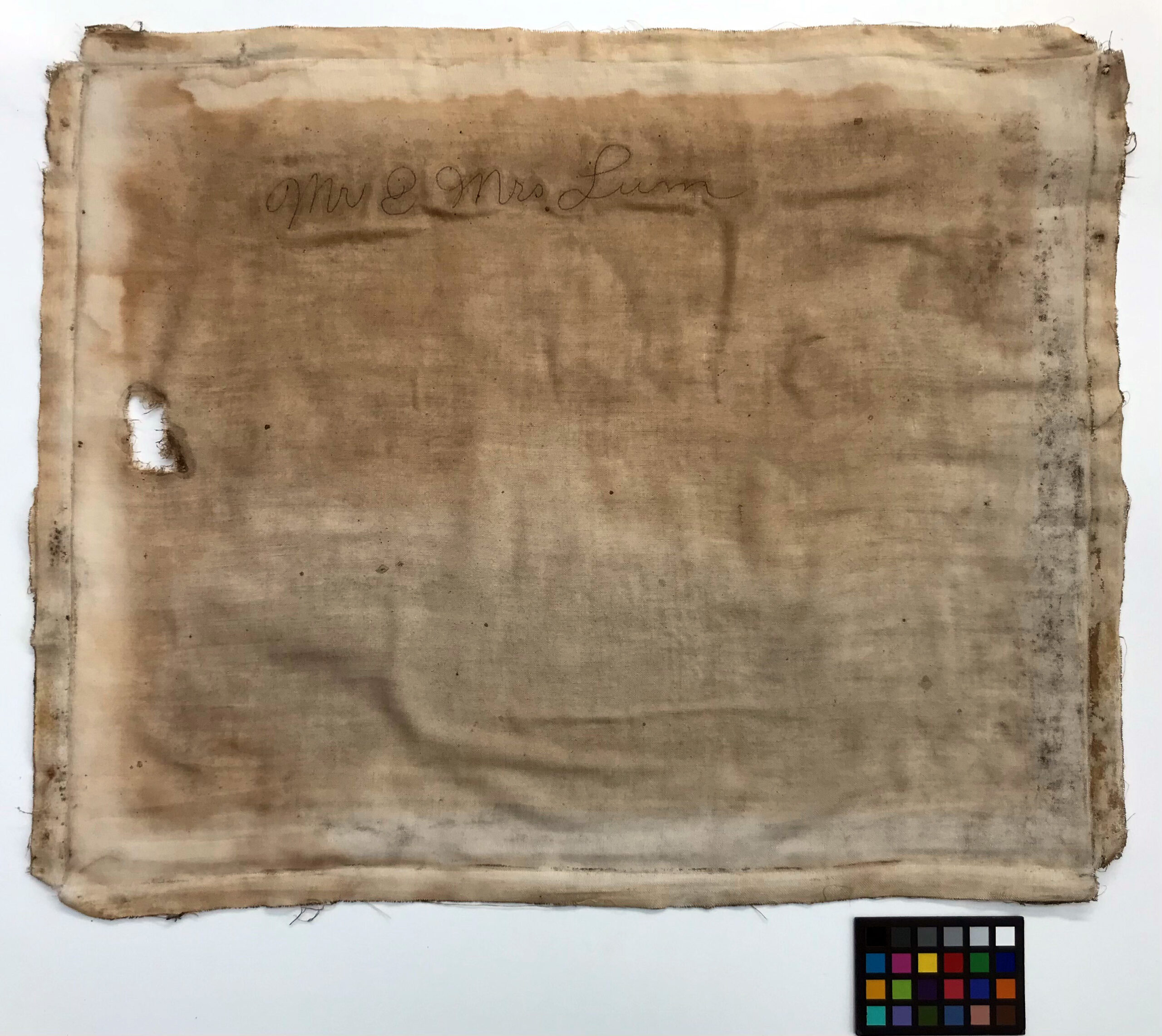

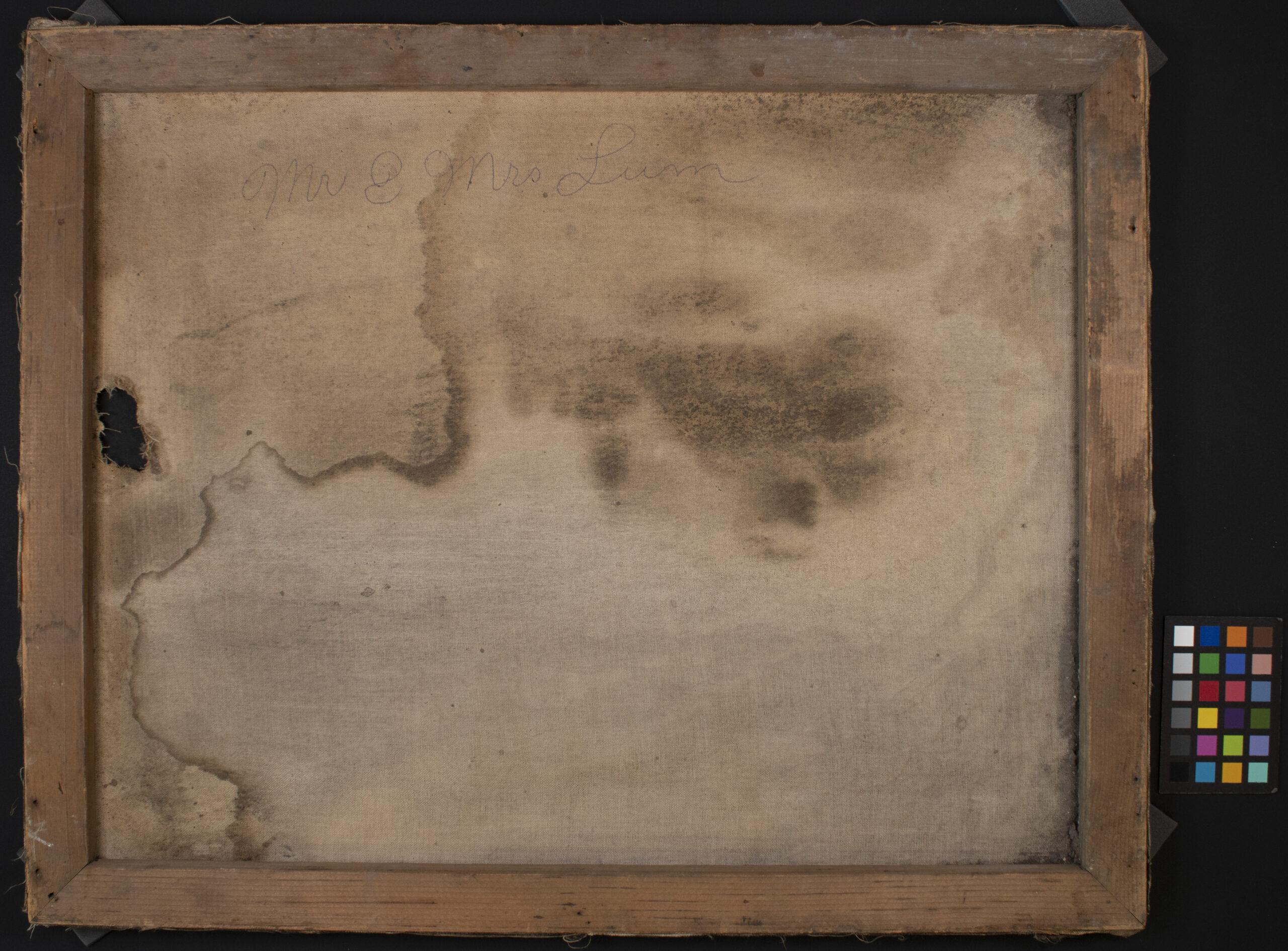

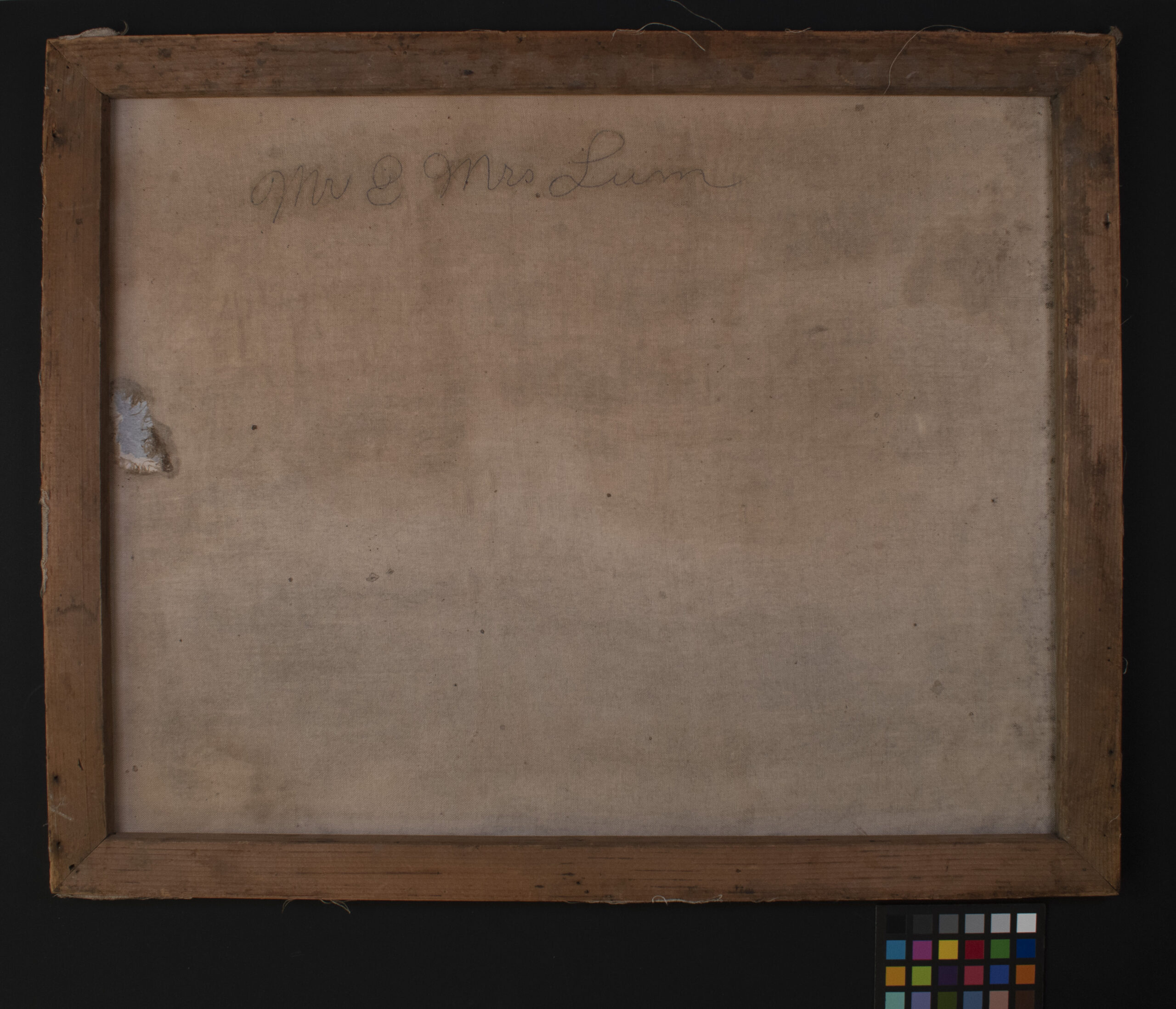

This portrait of Mr. and Mrs. Lum (BC Archives, J-01350) is one in a collection of four (BC Archives, MS-3411). Mr. Chin Lum Kee, also known as Ah Lum, was born in Guangdong (previously known as Canton), China in 1835. He arrived in the new colony of British Columbia during the Fraser River Gold Rush. While in Sto:lo territory, he met his wife, Squeetlewood, also known as Lucy, who was born in 1854.

The portrait is a solar enlargement, based on a salted paper print (more information on this type of photography below). Black and white crayon have been used to work up the figures’ clothing and watercolour has been used to add soft colouring to the faces and background. In keeping with photographic portraiture of the time, the figures are captured from the chest upward with their bodies fading softly into the bottom of the picture plane. This solar enlargement on paper has been mounted to canvas and stretched over a wooden strainer.

A Brief History of Solar Enlargements

Solar enlargements, also known as crayon portraits, were produced between the 1860s and the early 20th century. During the 19th century, photographic prints were made by placing photo-sensitised paper in direct contact with a photographic negative. Making a photographic print larger than the original negative began to be possible in the late 1850s with the invention of “solar cameras”. These enlarged prints required lengthy exposures and were faint and soft-focused. Furthermore, any imperfections in the photographic negative would be amplified in the enlargement.

As a result, these faint photographs were used as a sort of under-drawing upon which charcoal and coloured paints and crayons were used to retouch and enhance the image. It was common for artists to be employed alongside photographers for this purpose.

The most popular process for these enlarged photographic “under-drawings” was the salted paper print, however albumen prints could be used as well. Bromide enlarging paper was introduced in the 1880s which employed a gelatin emulsion layer available in many different surface textures. For more information on historical photographic processes, visit the Image Permanence Institute’s Graphic Atlas.

Condition Issues

The portrait of Mr. and Mrs. Lum came to the conservation lab because it was not in a condition where it could be safely handled. There was a large hole in both the paper photograph and the canvas behind it. The paper had been worn away along the left edge, resulting in a loss of some of the image. This is likely, at least in part, the result of some previous moisture damage. There were also tideline stains across the image from previous moisture damage. The adhesive holding the paper photograph to the canvas was disintegrating (or previously dissolved?) which meant most of the photograph was not actually attached to the stretched canvas support and was therefore more vulnerable to creases, rips and tears. Finally, the whole structure was heavily soiled with dirt, dust and debris.

Figure 3. Bottom edge of [Mr. & Mrs. Lum], before treatment. Photograph lifted to show underside of primary support (paper) and the secondary support (canvas).

Treatment

Treating a composite object is always difficult. Since this portrait was so heavily soiled and already stained by moisture damage, an aqueous wash (water bath) was deemed necessary. The decision was made to disassemble the object, which meant removing the partially attached photograph (or “primary support”) from the stretched canvas and then removing the canvas from the strainer. Each piece was then cleaned separately and reassembled once dry.

Cleaning the Primary Support

To be sure none of the media would be affected by washing, solubility testing of all the different media types as well as the staining was carried out under the microscope. The media was already thought to be quite stable—after all, it had survived moisture damage in the past—and the solubility tests proved this to be the case. The tidelines had mixed results with some appearing quite soluble and others less so. These results were enough to suggest that the primary support would benefit from a wash: the media would not be affected and the stains would likely disappear or at the very least, be reduced. Washing out these stains and other products created as a result of deterioration in the paper would also raise the pH, making the paper more chemically stable.

Figure 4. Recto of [Mr. & Mrs. Lum], before treatment. Paper triangles point to areas where solubility testing was carried out under the microscope.

Then, the solar enlargement was washed in an aqueous bath. There were some small fragments that had come detached from the left side of the photograph. These fragments were also washed but using a different, more delicate method. These fragments were gently placed on wet Tekwipe®, a non-woven fabric made from cellulose and polyester. This fabric has capillaries that draw clean water from one basin through the fabric, wetting out the paper resting on its surface and removing dirt and other products of deterioration in the paper and then move the dirty water along the rest of the fabric to the empty basin on the other side.

Figure 6. Primary support being removed from aqueous bath. Note the colour of the wash water has turned yellow with dirt and the water-soluble products that are formed as paper deteriorates.

Figure 7. Small fragments from the left side of the primary support being washed on Tekwipe® using capillary action.

Once washed, all pieces for the primary support were placed under weight to dry flat. After a few days of drying, the photograph was humidified and a thin piece of Japanese tissue paper was applied to the back. This lining provides a consistent support layer and prevents any further losses or tears around the areas that have already suffered losses.

Figure 8. Recto of solar enlargement after aqueous wash and lining with Japanese tissue. Note that some tidelines remain but they are reduced. The staining across Mrs. Lum’s face has been washed away.

Cleaning the Canvas

The canvas was gently removed from the wooden strainer and vacuumed on very low suction to remove loose clumps of dust and dirt that were deposited on the surface, particularly along the perimeter where the strainer had been.

The canvas was also heavily soiled and need a wash, however there is an inscription in blue ink on the back of the canvas that was discovered to be water-soluble during the solubility testing mentioned previously. To protect that ink from being solubilized during the wash, cyclododecane was applied as a temporary seal. Cyclododecane is a waxy substance that becomes liquid when warmed. It was applied over the ink as a warm liquid and solidified in place upon returning to room temperature. One of the unique properties of this wax is that it sublimes (passes directly from a solid state to a gas state) at room temperature over relatively short periods of time.

With the ink inscription temporarily sealed with cyclododecane, the canvas was washed with the help of textiles conservator Colleen Wilson. After the wash, it was allowed to dry and the cyclododecane was allowed to sublime, leaving the ink behind, unaltered.

Figure 9. Paper conservator, Lauren Buttle, applying cyclododecane to canvas to temporarily seal the water-soluble inscription in preparation for an aqueous wash.

Figure 10. Verso of canvas after being removed from strainer, with cyclododecane applied to inscription, before aqueous wash.

Figure 11. Textiles conservator, Colleen Wilson, blotting canvas with a sponge during first bath with detergents.

Figure 12. Verso of canvas 1.5 weeks after aqueous wash and after cyclododecane has fully disappeared.

Cleaning the Strainer

The wooden strainer was also vacuumed to remove surface dirt and dust. Some residual adhesive left on the outside edges of the strainer were re-moistened and removed with a Teflon spatula.

Reassembly

With all the individual pieces cleaned, the lined photograph was reattached to the canvas and then the canvas was re-stretched and adhered to the outside edges of the strainer. The Japanese tissue lining of the primary support provides support over areas of loss.

Re-Housing the Lum Portraits

While the main reason for diverting the Lum portraits to the conservation lab was to stabilize them for the move, there was also the issue of how to safely transport them. When they arrived in the lab, they were altogether in a paper folder, a housing system that was not offering sufficient protection in the context of a collection move.

Once conserved, this portrait, as well as the other three portraits in the collection, were placed in HTS (handling-travel-storage) frames. These storage structures are based on models developed by the Canadian Conservation Institute and the National Gallery of Canada. These frames will provide protection to each work and can be easily re-used for other similarly-sized works if necessary.

References

Canadian Conservation Institute (2018). “Framing a Painting – CCI Note 10/8”. Government of Canada. Framing a Painting – Canadian Conservation Institute (CCI) Notes 10/8 – Canada.ca

Reilly, James M. (1986). Care and Identification of 19th-Century Photographic Prints. Rochester, NY: Eastman Kodak Co.

Whitman, Katharine (2005). “The Technology of Solar Enlargements”, Topics in Photographic Preservation, Vol. 11, pages 104-110. Washington DC: American Institute for Conservation of Historic & Artistic Works. History (culturalheritage.org)

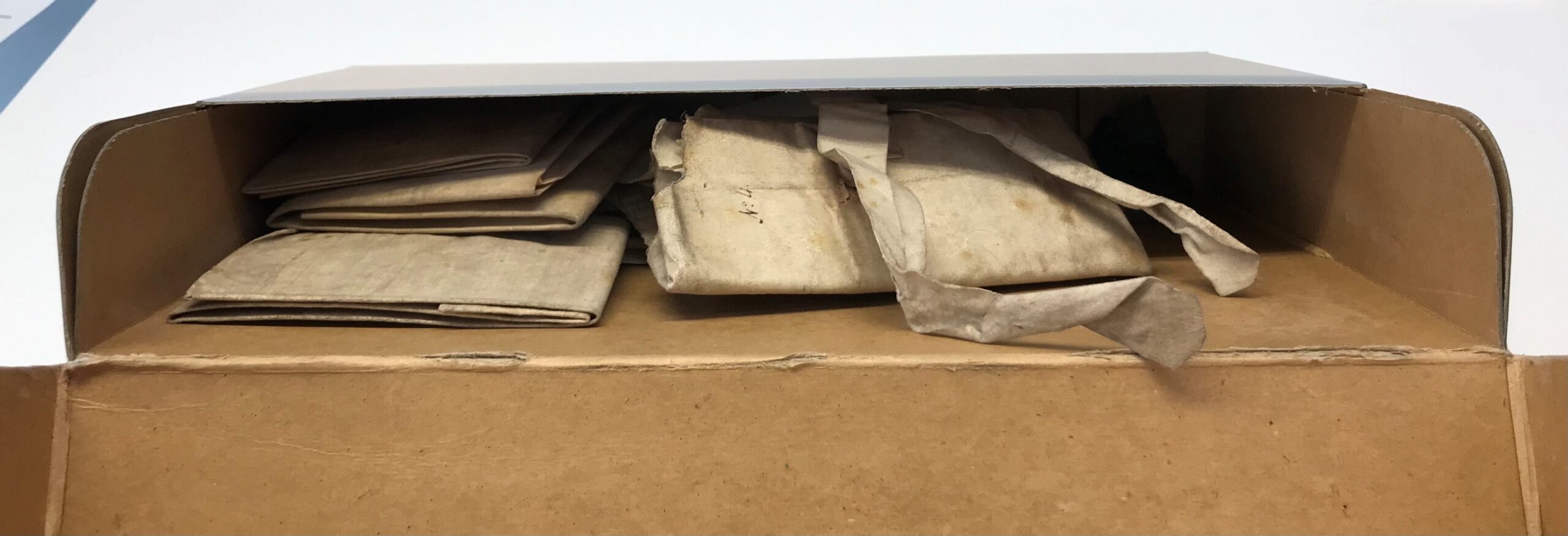

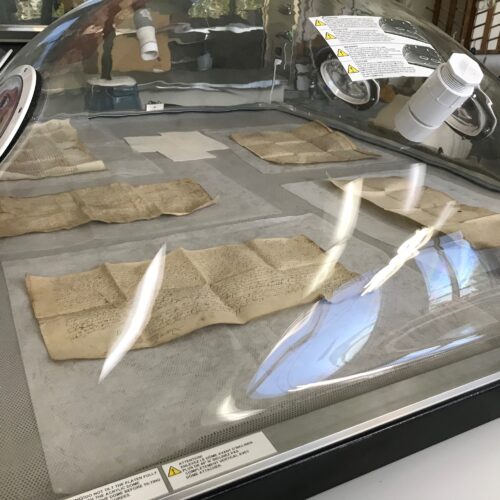

A few months ago, a box of archival records that had been requested for access was transferred to the Royal BC Museum paper conservation lab. These documents were part of the Archibald Menzies fonds, a small collection of records and belongings related to Archibald Menzies (1754–1842), a Scottish surgeon and naturalist who accompanied Captain George Vancouver aboard the HMS Discovery in 1791–95.

The documents in this box were mostly parchment and had been folded several times in the past, then piled into a box for storage. Upon retrieving the box, the archivist realised that none of these documents were easy to open. The parchment was hard and inflexible, suggesting that any attempt to forcibly flatten out the records might lead to damage. When problems like this arise, these materials are diverted to our conservation team for assessment and remedy.

So, how can we convince parchment to relax, open up and share its hidden secrets? First, we need to understand where it’s coming from.

The Nature of Parchment

Parchment is made from animal skin—usually that of a calf, sheep or goat. The skins are removed from the animal, dehaired and defleshed, and then treated with a lime or other alkali solution. After liming, the skin is dried under tension, and in some cases, surface treatments are carried out to make it more suitable to receive inks and paints. Before the invention of paper, parchment was a common writing support in Europe and parts of the Middle East. It continued to be used as such for several centuries after papermaking became popular and widespread.

Parchment is very sensitive to moisture and heat. This means that when water is present, the parchment will expand and absorb moisture. When conditions become warm and dry, the parchment will shrink and release moisture. Over long stretches of time, these cycles of shrinking and expanding cause the parchment to deteriorate, becoming distorted and hard.

Relax and Unfold

The parchment documents in this collection were tightly folded, and attempts to open them were met with strong resistance. Forcing them open could have potentially led to cracks, breaks and losses in the document; however, leaving them as they were meant that no one could read them.

To open these documents without incurring damage and loss, we needed them to relax. This state of inner peace was achieved with the careful introduction of moisture. Since parchment is so sensitive to moisture, the use of moisture to treat deteriorated parchment might seem counterintuitive; however, in the case of this treatment, moisture is delivered in the form of water vapour (never liquid water), and it was delivered with control.

The tightly folded documents were placed in an environmental chamber where the relative humidity (RH) could be raised using an ultrasonic humidifier. The RH levels were monitored throughout this treatment using a hygrometer placed in the chamber. Slowly, over a period of approximately two hours, the documents were unfolded bit by bit, until they were relaxed enough to fall completely open.

Once the documents had fully revealed themselves, they were placed under very gentle pressure between felt pads to ensure they dried flat.

A New Home

Now that these documents are open for viewing, they will be stored flat. They have been transferred to a flat storage box with custom padded trays for two of the documents, with seals and cords attached, ready for the next researcher.

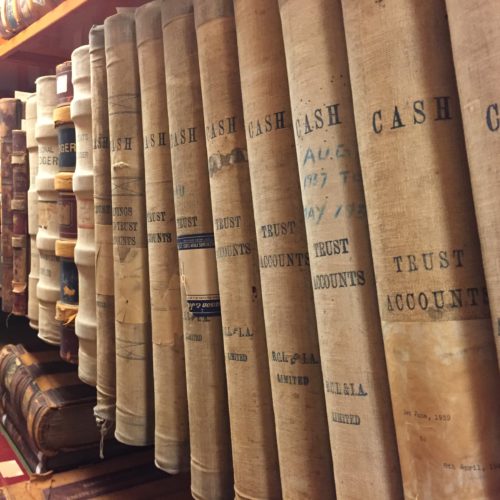

Every year the Government Records team at the BC Archives processes over 2,000 boxes of records created by the provincial government. Most of these records can now be accessed by anyone, even you! Just remember that all government records are covered by privacy legislation, such as the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act. This means some records have access restrictions on sensitive or personal information. Here is an overview of just a few of the record series from the last year or so that are now available in our database.

A page from the GR-4064 fire atlas. Each volume measures over three feet by four feet and weighed over 60 pounds.

A page from the GR-4064 fire atlas. Each volume measures over three feet by four feet and weighed over 60 pounds.

A selection of volumes from GR-3929, including the first patient file from 1870.

A selection of volumes from GR-3929, including the first patient file from 1870.

Bonus records! Here are some other records that were made available a bit before 2021, but are still worthy of a mention:

*These series include sensitive personal information or other restricted records that are not publicly accessible.

A public notice to be posted in schools, included with police records in GR-4000

A public notice to be posted in schools, included with police records in GR-4000

Government is constantly evolving to meet the needs of the citizens it serves. This often results in the renaming and reorganizing of its various branches and departments. These changes can make it tricky to track which government body was responsible for creating and maintaining particular records through the years. To help myself better understand who created some of the land records I was working with, I set out to create a visual representation of how the land management functions of government moved around over time. This soon expanded to include several other ministries whose records I worked on. It eventually grew to cover all ministries (and their precursor departments) from 1871, when the province was created, to 2021.

Please see BC Government Ministry History Diagram for the most current version of the diagram.

I created the chart using information from BC Archives authority records, Orders-in-Council and lists of Cabinet Appointments from the Legislative Library. Ministries are shown in square bubbles and are connected to each other with arrows. The oldest departments are at the top, moving down to the current ministries at the bottom of the page. The ministries are arranged in columns that represent broad categories of government functions, such as health or agriculture.

Arrows with solid lines show that a ministry was renamed. This usually means it continued to do pretty much the same work and fulfill the same functions of its predecessor.

Arrows with dotted lines show that some functions moved to another ministry. Dotted lines also show links from ministries that are established (created) and disestablished. I was only able to note large changes; sometimes the various branches that make up a ministry were split between a half dozen other ministries, making it pretty impossible to track all their movements individually.

The complexity and change over time make this a bit overwhelming to look at all together. But the changing names of a ministry can provide a high-level snapshot of general trends in government’s priorities over time. Each ministry is usually focused on a single function or issue, such as providing health care or managing public forests. The evolution of ministries reflects what government thought was important—and what mattered to voters. To a certain extent, this also reflects what mattered to society at large, though government was dominated by white men for most of the province’s existence, and universal enfranchisement did not occur until 1952.

Government departments changed very little from the province’s creation in 1871 until the 1970s. Government was small. Initially, the Attorney-General and Provincial Secretary were responsible for functions that would be divided among a dozen different ministers today. The major changes involved the creation of new departments as the role of government began to expand in the twentieth century.

Members of the Legislative Assembly demonstrating some pretty good social distancing. Photo taken in 1870 in front of the Victoria government buildings known as the Birdcages, after the union of the two colonies and just prior to Confederation. C-06178.

Initially, building infrastructure and promoting the industrial harvest of natural resources (to expand economic opportunities for other white settlers) appears to be more of a priority than providing social supports. For example, two separate departments for railways and public works were established almost 50 years before the Department of Health Services and Department of Social Welfare were finally created in 1959.

In 1976, all departments were renamed and became ministries. After this point, changes became much more common. By the 1990s it seems to have become fairly standard practice for a newly elected government to reorganize Cabinet, appointing new ministers to differentiate themselves from the previous government and reflect changing priorities throughout their term in office.

Some ministries have remained remarkably similar over the last hundred years. Others have been regularly broken up, combined and moved around in ways that, at times, can seem confusing and a bit counterintuitive. For example, in 1978, the Ministry of Recreation and Conservation was disestablished and broken into several ministries, including a new Ministry of Deregulation.

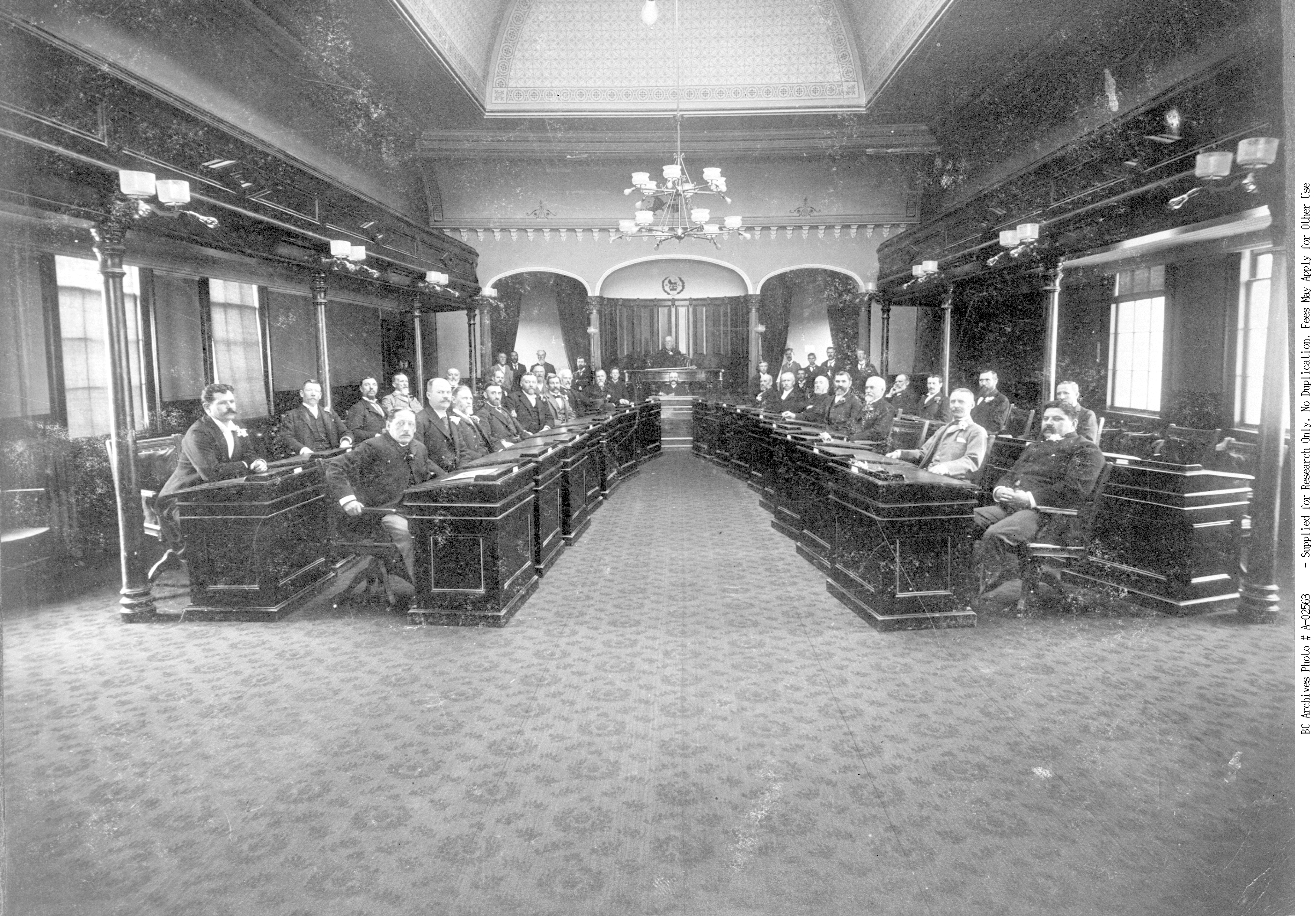

BC Legislative Assembly, Seventh Parliament, Third Session, in 1897 in the Birdcages. Construction of the current Legislative Assembly building was completed the following year. A-02563.

Names have power. Word choice can really impact how people perceive things, and the level of importance or value they place on an issue. The arm of government responsible for social services provides a good example of this. It has fulfilled fairly similar functions over time, but the language around the work has evolved alongside societal beliefs about poverty. It began in 1959 as the Department of Social Welfare. Later names included the Department of Rehabilitation and Social Improvement, the Ministry of Human Resources and the Ministry of Employment and Income Assistance. Currently, it is the Ministry of Social Development and Poverty Reduction.

Establishing (or disestablishing) a ministry shows that government is assigning its affairs a certain level of importance, with an elected official appointed to focus on the function or issue. The creation of a Ministry of Women’s Equality in 1991, when BC’s first female premier Rita Johnson was in power, shows women’s equality was an important issue for government at the time. In 2001, this ministry was disestablished and lumped into the Ministry of Community, Aboriginal and Women’s Services with four other disestablished ministries, including the also-disestablished Ministry of Aboriginal Affairs.

Overall, I have found the chart a helpful way to track government’s changing responsibilities at a glance. My hope is that it can be a useful tool for researching archival government records. A record’s creator (often the ministry or department that created it) is one of the main things archivists look at when arranging and determining different series of government records (GR-numbers) in the BC Archives database. If you can think about the ministry that may have created the records you are looking for, it may provide access to some unexpected results. You can search for archival records by creator here.

Happy researching!

As a government records archivist, I process a lot of records related to land or resource use, and specifically forestry records. Since the beginning of British Columbia’s colonization, forestry has been a major part of the province’s economy. After over 150 years of industrial logging, the majority of the province has been disturbed by some kind of industrial activity, leaving an estimated 2.7% as productive old growth forest today.

Most land in the province is Crown land controlled by the provincial government. Crown land and resources—in this case timber—are leased or licensed to forestry companies to use. These agreements are generally referred to as timber tenures and can include a variety of uses, lengths of time they are valid for and other required management practices.

Managing all these resources has created a huge amount of government records. Many of these are now kept by the BC Archives for government reference and historical knowledge, and so that the public can hold its government accountable. I recently processed a series of records related to forestry in the Clayoquot Sound area, now part of GR-3659.

GR-3659 documents a type of timber tenure referred to as a Tree Farm Licence (TFL). Most of western Vancouver Island is covered by a handful of TFLs. TFLs provide a forestry company with almost exclusive rights to harvest timber and manage forest in a certain area for 25 years. Every 5 years, companies are required to create detailed plans outlining how they will manage the land and resources within the TFL area.

Working with the records in GR-3659 got me thinking about a related historical event—the 1993 Clayoquot Sound protests, also known as the War in the Woods, which occurred primarily on TFL 54 and TFL 57. So, I took a look at some of the other records that document it.

Protests and blockades began in the 1980s after logging was proposed on Meares Island in Clayoquot Sound. Several attempts were made by the government to reach a consensus between the members of the forest industry, environmentalists, municipalities and Indigenous Peoples. These included the Clayoquot Sound Development Task Force (GR-3535, box 921203-0023) and the Clayoquot Sound Development Steering Committee. Environmentalists left the Steering Committee in 1991 after the government refused to defer logging until an agreement was made. The Steering Committee ultimately dissolved in October 1992, without completing a finalized development strategy.

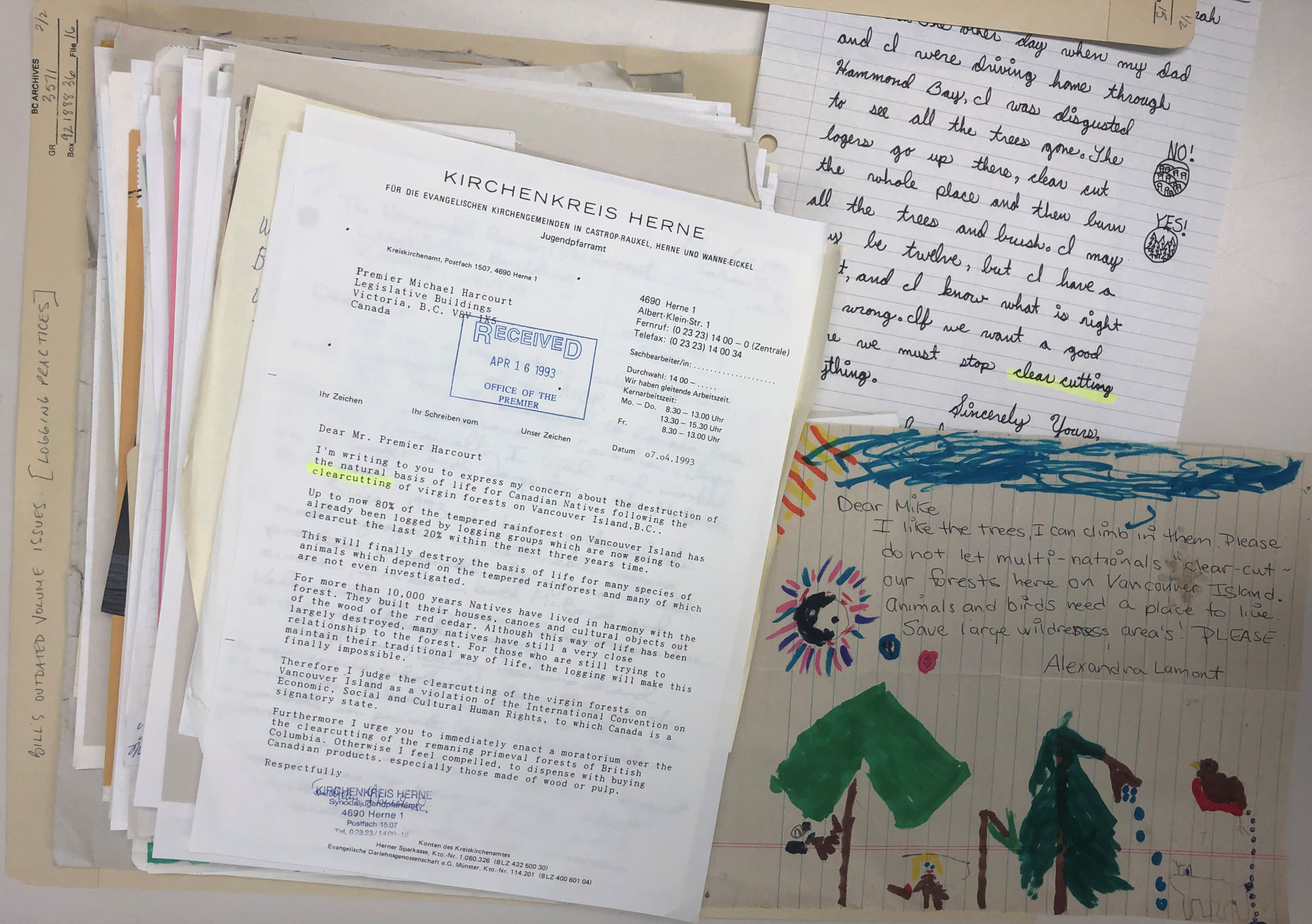

A few months later, in April 1993, Cabinet passed the Clayoquot Sound Land Use Plan, but it was widely contested. The government’s lack of consultation with local First Nations and the large area of old growth forest available for clear cutting resulted in protests that spread around the world. Protest camps and blockades were set up to prevent logging, in defiance of court injunctions. Police attempts to enforce the injunction led to over 800 arrests. Thousands of people protested over the summer of 1993, making it possibly the largest event of civil disobedience in Canadian history.

Ultimately, the government was able to reach a consensus with the Nuu-chah-nulth First Nation, whose traditional territory includes Clayoquot Sound, and new land use plans were developed. This also led to the creation of Iisaak, a new First Nations owned logging company operating in the area (some of their records are in GR-3659), and the designation of Clayoquot Sound as a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve.

Letters protesting old growth logging received by the Premier in 1993 from across Canada and the rest of the world (BC Archives, GR-3571, box 921888-0036, file 16)

I’ve been thinking a lot about gratitude.

At the end of last year, an article I wrote titled “Gratitude in the Archives” was published in Garland Magazine. You can read the article here:

https://garlandmag.com/article/gratitude-in-the-archives/

When the staff of the museum and archives were sent home in March due to the COVID-19 pandemic, I felt many things, including anxiety, fear and uncertainty. As time went on and I settled into my new routine of working from home in a house vibrating with the play of young children, other feelings began to creep in. I tried to concentrate on the positive things, and I found that, as I described in the article, rituals of thanksgiving help me to focus on the present.

Preparing to return to work, I look forward to surrounding myself with records once again (nothing beats that old paper/book smell!) and connecting with researchers. I am thankful to find myself working in a profession that I truly love. Although much has changed this year, the sentiments expressed in last year’s article remain accurate: as ever, approaching my work with gratitude allows me room to grieve the past and be thankful for the present.

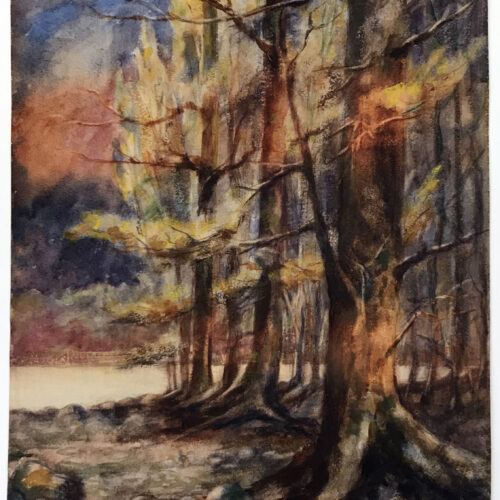

In 2017, the BC Archives acquired an Emily Carr watercolour of a woodland scene (PDP10276, Fig. 1). The work is an example of Carr’s early interest in the landscape of British Columbia. Recently, the work made its way back to the Paper Conservation Lab to receive the treatment that was recommended at the time of acquisition.

When this work arrived at the Royal BC Museum, a few condition issues were apparent. There was some evidence of fading, a small stain in the upper left corner and some microscopic cracking of the paint layer (Fig. 2), but these issues are irreversible and— now that the painting is entering a stable, museum storage environment—not particularly worrying. There was, however, one big (and unsightly) problem: the painting had been adhered to a low-quality, acidic cardboard support at some point in its history, and that support layer had been partially torn away (Fig. 3).

Why is this a big problem?

Mechanically:

Chemically:

Treatment

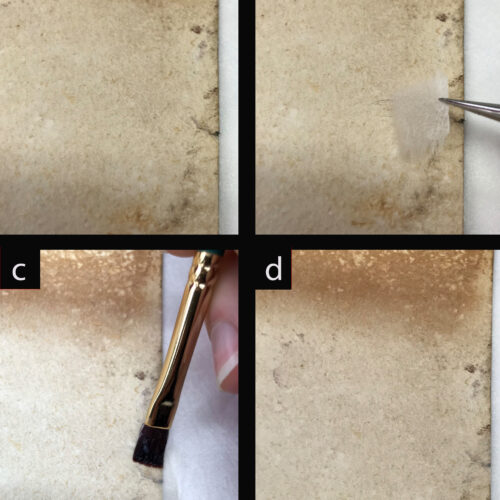

The solution was clear: this partial backing had to be fully removed.

Removal of a backing usually happens in stages. The backing board attached to this painting was rigid and thick. Trying to remove something thick from something thinner all at once will usually result in tears, delamination and/or creasing in the thinner, more flexible object—in this case, the painting. To avoid this, the thick backing is removed in thin layers. The backing is reduced, layer by layer, until we reach the final layer, which is attached to the painting. This final layer is the one carrying the adhesive, which makes it the trickiest layer to remove and the layer that needs to be removed most delicately.

The initial layers were removed using a thin, slightly dull blade. Upon reaching the final layers, it was apparent that there were many areas, particularly towards the outer edges, that were not directly adhered to the back of the painting. These areas lifted up easily without the blade.

The remaining, adhered portion was tested with a small amount of distilled water under the microscope and fortunately, the adhesive was discovered to be water-soluble. To be sure that the application of water on the back would not solubilize the media on the front, the media on the front was tested under the microscope with small drops of water (Fig 4). Each different colour was tested in discrete areas. Fortunately, only one colour was partially affected by the water. Given the thickness of the paper and the sensitivity level of the paint, it seemed unlikely that the water used for the backing removal would cause damage, and therefore a small, controlled application of water, administered under the microscope, was used to remove the final layer of the backing.

Following the backing removal, a small tear along the left side of the work became unsupported and therefore, unstable. To prevent this tear from growing bigger, it was repaired by pasting a thin piece of Japanese tissue over the tear on the back (Fig 5). The Japanese tissue is made of long natural fibres, which makes it very strong and supportive, despite how thin and translucent it appears after application.

Now that the work is physically and chemically stable, it is ready to be mounted so that it can be made accessible for research and exhibit (Figs. 6 and 7). Once the work is matted and framed, the change from “before” to “after” won’t be detectable to most viewers, but this work is essential for the long-term stability of the painting. It is an invisible gift that this generation bequeaths to the next.

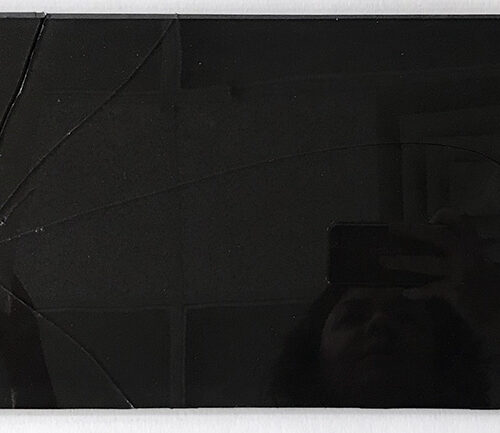

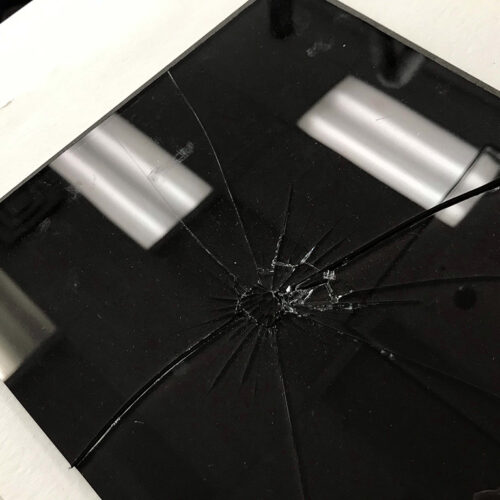

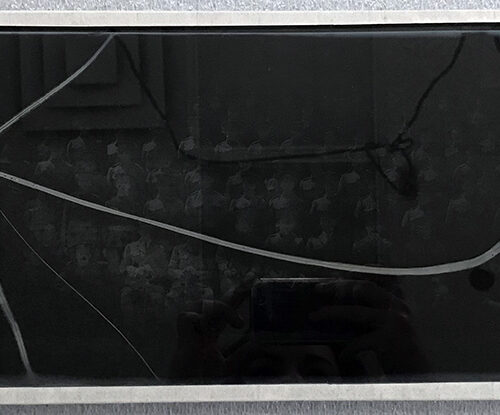

The BC Archives is currently finishing up a project to arrange, describe and digitize a collection of photographic holdings from Ernest Crocker, a notable nineteenth century photographer. Part of this effort has involved some conservation work to repair some of the elements of these collections that have not made it through the ravages of time in one piece. In this particular example, the image identified as J-02623, there were a great many pieces. The following is a description of how it was repaired.

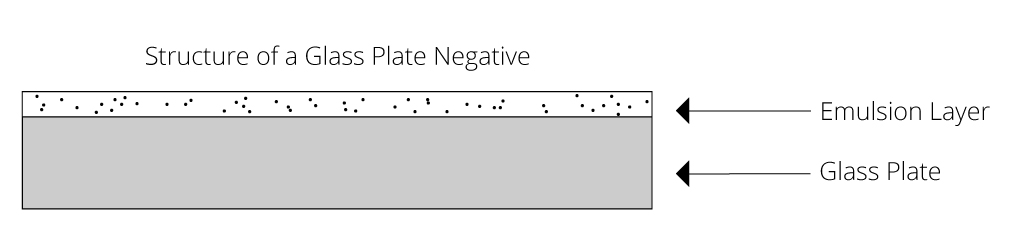

Background and terminology

Glass plates were used as a support for photographic negatives early on in the history of photography and continued to be used well into the first half of the twentieth century. The negative is composed of two layers: the glass support and the photographic emulsion that holds the image (Fig 2). In the case of this example, the emulsion layer was made from gelatin.

Condition issues

When J-02623 arrived in the conservation lab, it was in many pieces and was resting on a second, intact plate. The fractures radiated from a central point near the upper right corner, suggesting that the negative had been struck by something blunt at some point in its history. In some of the areas around the cracks, the glass had been reduced to dust, which meant that there would likely be small losses once the dust was cleared. Its fragmented and fragile condition meant that it could not be removed from the supporting negative underneath it, which meant that the archivist could not see or identify either image and absolutely couldn’t digitize them.

These condition issues posed a few interesting problems in terms of developing a conservation treatment:

1. Broken plate cannot be stabilized as it is

Cracks in glass plate negatives are not uncommon. In many instances, simple solutions such as custom storage enclosures or pressure mounts are sufficient for long-term stability. Pressure mounts—two new pieces of glass put on either side of the broken original and taped together—were used on several other broken plates within this collection. The benefit of this method is that the new glass provides the necessary support for the plate to be handled again and the treatment is completely reversible, allowing for reconsideration of treatment alternatives in the future if desired. In the case of J-02623, however, this would not be feasible—the negative was too fragmented and would not be adequately supported by a pressure mount alone.

2. Broken plate cannot be moved as one piece

Before methods for consolidation and long-term storage could be considered, the issue of simply removing the broken plate from the intact plate beneath it had to be addressed. As previously mentioned, areas around the cracks had disintegrated into dust. This meant that sliding the broken negative off of the supporting plate and onto a new piece of support glass would be impossible. Some of this sharp, glass dust was likely to be under the broken shards of the negative. If sliding was attempted, the glass dust would act as sandpaper, abrading the delicate emulsion on the underside of the broken negative, leading to partial losses of the image. It would also likely scratch the glass side of the other negative as well.

3. Reassembly after any disassembly would be very tricky

If the broken pieces couldn’t be slid onto a new support or work surface, they would have to be lifted. But this solution posed its own problems: how do you replace so many tiny pieces back in proper alignment once they’ve been disassembled?

4. How to stabilize for the long-term

Once a plan to remove and reassemble the broken plate is achieved, how do you stabilize it for gentle handling and digitization? If a pressure-mount system is not enough, the only other option is to adhere all of the shards back together; however, this is easier said than done. How do you apply adhesive to glass shards without it oozing out around the edges? What adhesive will provide a strong enough bond while also having good aging properties as well as being reversible/adjustable?

Treatment

Figure 6. Paper conservator Lauren Buttle applying adhesive to glass side of J-02623 using Silpat® method. A respirator mask was required for this treatment because of the use of solvents.

A carefully considered treatment plan was required to answer so many questions.

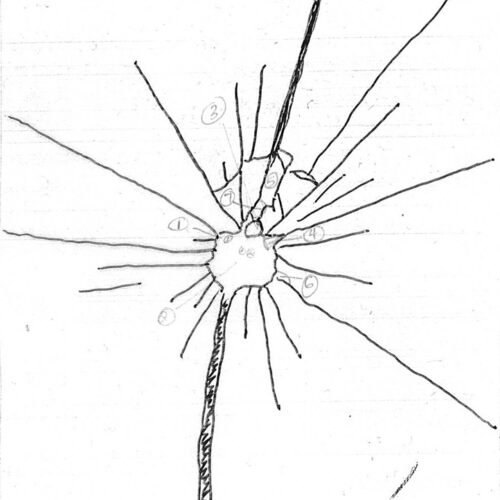

To achieve the first task of moving the broken plate to a new working surface, the damage was first mapped (traced) onto a clear sheet of plastic with permanent marker and photocopied onto paper. This map was used as the basis for recording the location of each of the tiny shards that would have to be replaced afterwards. Tiny shards that were big enough to carry part of the emulsion were removed one-by-one, placed in a numbered bag and their shape and location was noted on the map (Figs. 4 and 5).

Before the shards were reassembled, the edges of each one were swabbed with acetone to clean away any dirt or oil that might impede adhesion. The shards were reassembled, emulsion-side down, on an inclined surface against a Silpat® mat (a reusable silicone-covered textile designed for baking). This mat provides a non-stick surface that is not completely flat. The texture in the textile provides a series of small bumps that raise the glass slightly off of the rest of the surface. The adhesive is delivered to the cracks on the glass side and capillary action draws the adhesive through the crack. Because there is no consistent contact with a flat surface on the emulsion side, the capillary action stops at the emulsion side, keeping the edges of the cracks on that side nice and neat. All of the pieces were assembled dry first. After all pieces were aligned, adhesive was administered.

After the adhesive in the cracks was dry, the glass-side surface was cleaned gently with solvents to remove any adhesive residue from the edge of the cracks.

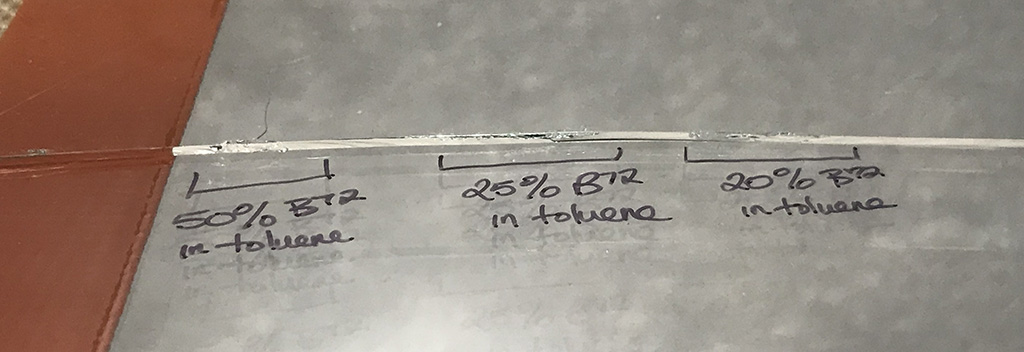

The adhesive used for this repair was Acryloid B-72, a non-proprietary acrylic adhesive with known aging properties and good long-term stability. Acryloid B-72 can be dissolved in many different organic solvents. In this case, toluene was used, because it has a relatively slower drying time, which allows more time for the solvated adhesive to flow into the cracks before drying. Various concentrations were tested until full penetration of a crack in a test piece of glass was achieved (Fig. 7).

Figure 7. Test glass with different concentrations of Acryloid B-72 in toluene applied to a crack. When light is shown over the crack, the areas where the adhesive has been drawn in begin to disappear.

After all the pieces had been assembled and adhered in place, the plate could be lifted and handled gently. But due to the larger size of the plate and the amount of cracking, additional support would be needed for long-term care and access. Also, there were small losses in areas in the center of the cracking, which left jagged edges exposed. For these two reasons, it was decided that a pressuremount would be the best way to protect the plate and the patron.

Two new sheets of glass, cut to the same dimensions as the negative, were cleaned and placed on either side of the repaired plate. All four edges were taped to seal the package and allow for easy handling. The plate will be transferred to a member of our Preservation team for digitization with the rest of the collection.

For more information on this collection, see the Ernest Crocker Fonds (PR-1348) on the BC Archives website.

Acknowledgements

The techniques for repair discussed in this blog were based on the methods conveyed by Katherine Whitman, conservator of photographs for the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) at a workshop hosted by the AGO in October 2018. My attendance at that workshop was generously sponsored by the Koerner Conservation Initiatives Fund through the AGO and the Royal BC Museum. I am also grateful for the ongoing communications with Katherine Whitman in devising a treatment for this plate.

Thank you to Joel Blaicher, exhibits fabricator for the Royal BC Museum, for building the support that was used in this treatment. Thanks also to Rob Anderson, lighting and AV specialist for the Royal BC Museum, for his assistance in creating a time-lapse video of this treatment.

Views of Victoria post

Frank Stanley Martin was a Victoria jeweller who made a hobby of photographing the city in the 1950s and 60s. He was also pretty good about identifying the photographs which makes the work of an archivist much easier. A small batch of his photographs were donated to the BC Archives in 1985 and I recently did a fonds description for them, pulling together the items that had been described and sometimes digitized. My colleague Chantaal, kindly digitized the ones that had a descriptive record but no image attached. I went back to the original photographs and made sure they had the titles and information that Martin had written on the back of each one.

I enjoyed looking at these photographs, particularly because Victoria is undergoing such a change right now. There are cranes, scaffolds and building sites everywhere and sometimes its difficult to remember what the city streets looked like just a few decades ago. You can see the fonds description for PR-2382 and the 62 digitized images here

I like this one because this photograph taken at the corner of Government and Humboldt St. could have been taken last week.

I-68492

I recently came across a small batch of letters while I was looking for something else. The letters, described as PR-1615, were to Matilda John of Victoria. They were written to her in 1899 and 1900 by her young boyfriend Harold Penn Wilson as he traveled from Victoria to Bennett and later Atlin. Wilson worked for the Merchants Bank of Halifax and had been sent to their new office in Bennett. The letters are mostly interesting in how they describe the journey from Vancouver to Bennett, and what it was like to live in the North at the turn of the century for a young bank clerk. But there is also some gentle romance; Harold asked Mattie for a lock of her hair and claims that he is wearing her “badge”. Harold was 19 and Mattie was about 16.

Harold and Matilda never married, he eventually married someone else in Prince Rupert, and died back in Victoria in 1975. I haven’t been able to find out anything about Matilda. There is a photograph of a Matilda John in our portrait files which may be her. She is dressed in what looks like a nurse’s uniform.

Matilda kept the letters and they made their way to the Archives at some point. They are quite fragile so they have been digitized by the Preservation team and now anyone can read them by clicking on the letter showing in the description and downloading the pdf file.

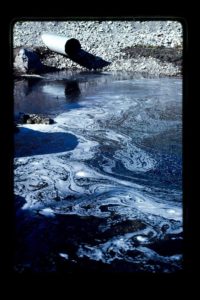

Last year I came across an interesting document. It is a Memorandum of Cooperation between British Columbia and the State of Washington and was signed in July 1972 by Premier W.A.C. Bennett and the Governor of Washington, Daniel J. Evans. It is a simply written two-page document outlining the desires of both parties to protect the Strait of Juan de Fuca, the Strait of Georgia, Puget Sound and their adjacent waters from oil spills.

The document came to the BC Archives in 1973, from the Office of the Deputy Provincial Secretary and had been stored offsite with just a control number.

I rehoused it and made a descriptive record and recently our preservation team scanned it at my request. Now anyone can read the document by clicking on the image and downloading the pdf, GR-0160

Along with some 1977 photographs of oil spill experiments, it offers a glimpse into some of the prevailing issues in that decade.

I-20083

I-20081

I-20086

Ship pics post

Don’t say that too quickly.

I recently enjoyed looking through an old photograph album that was given to the Provincial Library and Archives in December 1937. The album was donated by Major Harold Brown, Managing Director of the Union Steamship Co. Provincial Librarian W. Kaye Lamb noted that the photographs were probably taken around 1924-1925.

We don’t know why Brown created the album, maybe it was useful to have photographs of the Union Steamship Co. ships (and others) to hand when doing business.

Over the years we have scanned about 147 of the 250 photographs in the album. They can be viewed online with their description MS-3079.

I am interested in the ones that show some kind of port activity like this one of the tug Helac and the Kaga Maru at what looks like the Vancouver Harbour.

But this one is quite sad, it’s the Toyama Maru in Vancouver Harbour. Twenty years later it would be sunk by the USS Sturgeon, killing over 5000 Japanese soldiers and sailors.

Saturday was International Archives Day. This year’s theme is Governance, Memory, and Heritage. It’s a broad subject, but it really covers the essence of what we do.

Part of my job involves giving tours of the BC Archives, often to groups of people that have never used an archives or considered doing archival research. In my 10 minute “Archives 101” introduction I start with one of the main tenants of why we keep records: because archives are a mainstay of democratic governance. Embedded in democracy is the right of the people to access information about themselves and their government. In theory we keep about 5% of all the records created by government, but that small percentage should capture the good stuff: decision making documents, policies, annual reports, and other summary records that illustrate what a particular government office was doing at a moment in time.

Government records are great for giving an overview of society, but they can be somewhat dry – and so much of society operates outside of government. For this reason, the BC Archives long ago adopted a “total archives” approach, seeking to fill in the gaps in the record by acquiring the records of individuals, families, businesses, and organizations whose impact was provincial in scope. Of course, deciding what records fit this mandate is subjective, and institutional interests or priorities can be evident in collecting practices over time. Ensuring that the spectrum of humanity and experiences in BC are reflected in the archives is a challenge, and we must continually evaluate the work that we do, recognizing that there will always be silences in the record, and that often what we don’t find in the archives is as important as what we do find.

One thing you can be sure to find in the archives is variety. From the people and the places described, to the format that the information is found, there is more to the archives than most people expect. A record is any recorded information: textual (written records), cartographic (maps, plans, architectural drawings), audio-visual (sound recordings and moving picture recordings), graphic (photographs, paintings, drawings and prints). For International Archives Day, we wanted to highlight a few of our diverse collections. But how can we choose among the thousands of series? I’ve selected a few today, but the @BCArchives twitter account will continue to highlight our records by tweeting a “Featured Collection” twice a month from now on. Although some of what we share may have restrictions on access, we hope they give a sense of the fascinating information found in the stacks at the Archives!

FEATURED COLLECTIONS:

GR 3571 – Premier’s Correspondence. 131 m textual, photos, audio, ephemera. These records cover the period from 1974 to 2008 and document ordinary peoples’ reactions to “hot topic” issues of the day such as old growth forestry logging, RCMP officers wearing turbans, the tainted blood scandal, and government funding of AIDS medication. Included are some children’s letters and art from school groups. This collection is may have some restrictions on access.

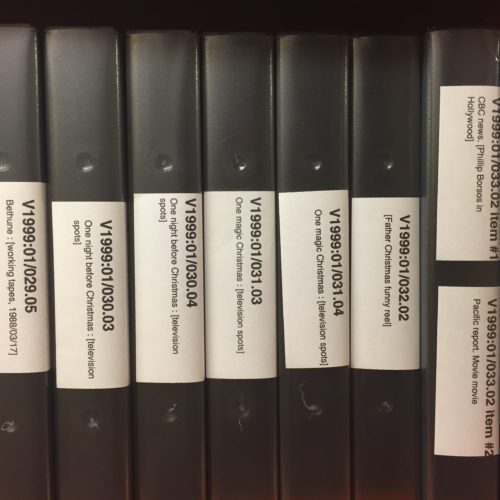

PR-2086 Philip Borsos fonds. 22 metres of multimedia material including film reels, magnetic tracks, optical tracks, optical discs, video reels, videocassettes, audio reels, audio cassettes, audio compact discs, photographs, technical drawings, maps, prints, production boards and computer disks. Borsos was a filmmaker with a career spanning 1970 – 1995. The film projects chronicled include the documentary shorts “Cooperage”, “Spartree”, “Phase Three”, “Nails”, and “Racquetball”, and the features “The Grey Fox”, “One Magic Christmas”, “Bethune”, and “Far from Home: The Adventures of Yellow Dog.” The fonds also includes Borsos’ journals and miscellaneous personal papers.

GR-3377 – Provincial Archives of British Columbia audio interviews, 1974-1992. Consists of 440 sound recordings. The series consists of oral history interviews recorded by staff members and research associates of the Provincial Archives of B.C. Major subject areas include: political history (especially the Coalition era, the W.A.C. Bennett years, and David Barrett’s NDP government); ethnic groups (including Chinese- and Japanese-Canadians); frontier and pioneer life; the forest industry; B.C. art and artists; the history of photography, filmmaking and radio broadcasting in the province; and the history of Victoria High School. This is one example of many oral history collections at the Archives!

GR-0419.34A – Attorney General documents, 17 (1887). 235 pages. File includes correspondence and other records relating to the so-called “Kootenai Uprising.” Records describe the dissatisfaction of the Ktunaxa with their assigned reserve lands; the accusation of two Indigenous men of murder, followed by the arrest of one called Kapla, and his subsequent escape with the assistance of Chief Isadore; and the deployment of the North-West Mounted Police, led by Sam Steele, to the region. Of particular note is a verbatim transcript of a speech delivered by Chief Isadore in July 1887.

PR-1380 – Frederick Dally fonds. 7 cm of textual records, 466 photographs, 1 map. Frederick Dally was born in Wellingborough, Northamptonshire, England in 1840. He arrived in Victoria, British Columbia, in 1862, on the China Clipper “Cyclone.” In March 1864, Dally leased a store at the corner of Fort and Government streets, and in 1866 he opened a photographic studio in Victoria. Between 1865 and 1870, he took extensive photographs around Vancouver Island and in the Cariboo District.

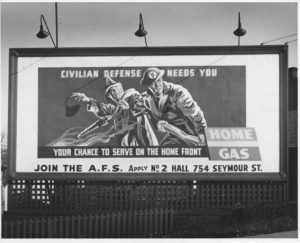

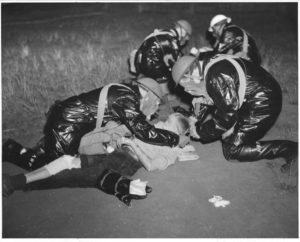

Last summer I worked with some really interesting records that illuminated the “Home Front” situation in British Columbia during World War 2.

Activity, particularly in the realm of Air Raid Precautions (ARP), was a curious mixture of official and civilian partnership. In 1942 Premier John Hart formed the Advisory Council, Provincial Civilian Protection Committee to assist and advice the official Provincial committee in the organization of air raid precautions in the province.

The Advisory Council took on a lot of administrative work in distributing grants to BC communities to buy equipment, train volunteers and disseminate information.

The records of the Committee are with the BC Archives and are described as GR-0268. Last year I found three boxes of missing records and added them to the series. The series description can be viewed here.

The records are open for access but are stored offsite so can take a few days to bring in.

There are also some photographic records created by the Advisory Committee which I had a lot of fun working with. One series, GR-3644, consists of 77 b&w photos of ARP activity. Our preservation unit has scanned these so they can now all be viewed online.

Some of my favourites include I-78009 (children learning to use respirators), I-78029 (volunteers receiving training), I-78002 (recruiting poster) and I-77973 (gas decontamination crew during practice)

Sometimes the most mundane tasks can lead to the most interesting discoveries.

One of those mundane but essential tasks is the compilation of inventories. My department wants to ensure that all of the colour transparencies and slides of our Paintings, Drawings, and Prints (PDP) collection have been scanned, uploaded and attached to their online descriptions in AtoM. We need an inventory to assist with this. It’s a pretty straightforward process: I look at the transparencies, list them by PDP number, determine if the image is already available in our digital repository, check that a description exists in AtoM, and see if a scan of the image already appears online. I have a good eye for detail, and I find a number of anomalies I’ll need to straighten out.

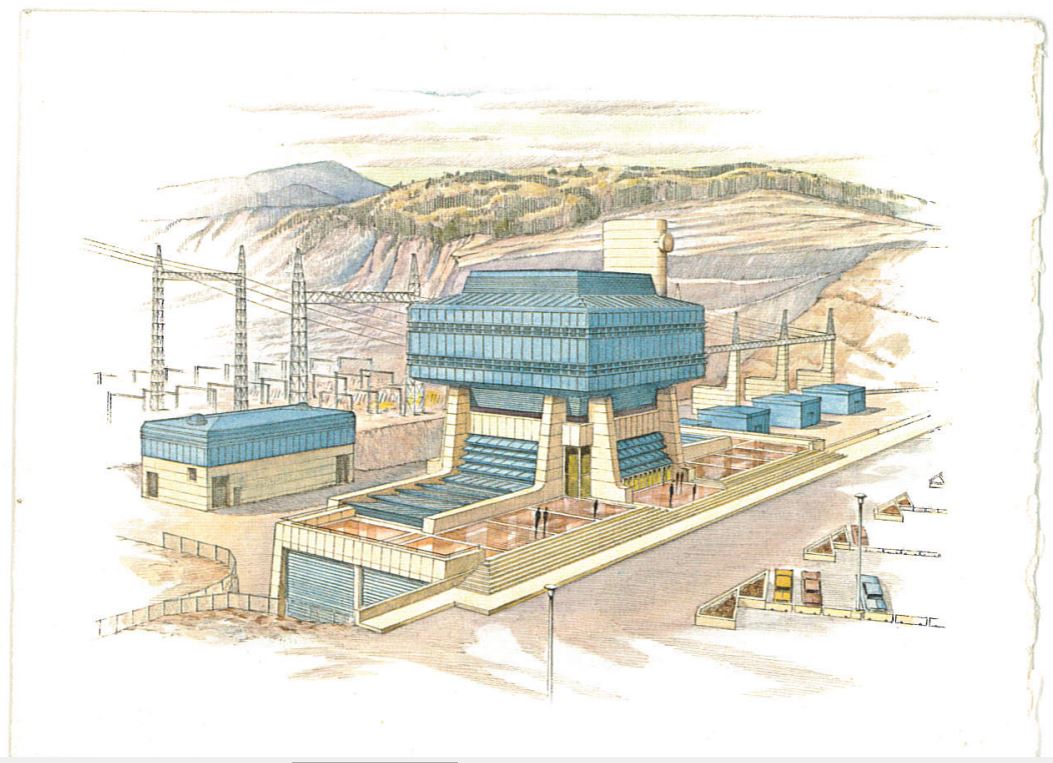

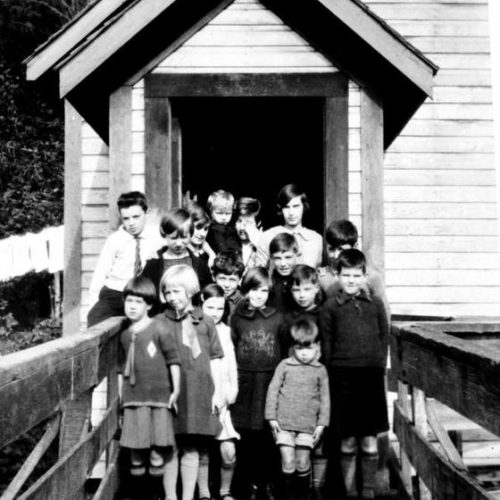

Then I lift a transparency to the light and I see a colourful image that reminds me of the folk art of Maud Lewis. I pick up another, and it is more of the same. These images I am holding in my hands are colourful, and with one or two there is a sense of whimsy. I think it is the sense of motion and the relationship between space and perspective that reminds me of Lewis’s work. Taken as a group, they are very detailed and technical–yet they are not technical drawings.

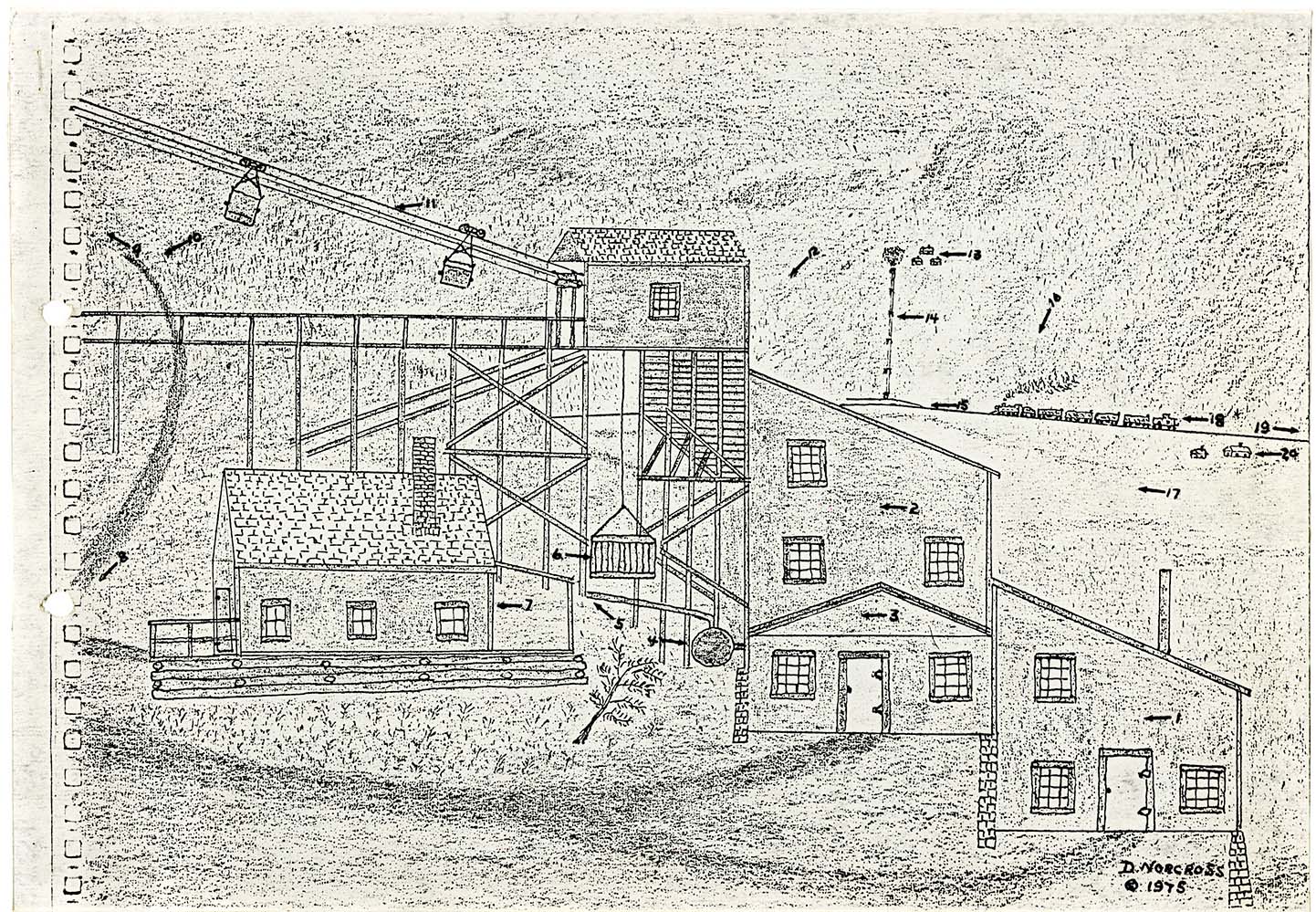

These transparencies make me eager to see the originals. A colleague and I go into the PDP vault and locate the container. We find that the colours in the originals are far brighter than those in the transparencies; they appear to be drawn in pencil crayon. The subject of all of the drawings is mining in British Columbia. We’re entranced by the originals—the passion the artist has for his subject is clearly evident.

While compiling his memoirs, David Henry Norcross (1901-1980) gathered his drawings of early mining into a collection he named “Recollections 1975.” The container holds more than the colour drawings. Within a brown binder anchored by a metal clip, there is photocopied material meant to act as an index or finding aid to the images. This material includes copies of the drawings and written commentary to accompany each image. This includes description of machinery, transport, mining tools, miners, mine sites, and history. On the copies of the drawings, Norcross has numbered certain points, which then correspond to points in the commentary. Unfortunately, the paper appears to be from an earlier form of photocopying, and the ink used on it has already faded. I’m glad that I’ve discovered this in time, and I make a digital preservation surrogate. Now, at least, we will have a stable preservation copy of the information provided by Norcross.

The man who made these drawings also wrote “I am not an artist” in the introduction to his material. I think that simple statement expresses one rationale for our PDP collection. It is a documentary art collection, where the pieces are acquired and preserved because of the visual record they provide of British Columbia’s past. This isn’t about pieces of fine art; it is about documenting specific times and places, people and activities.

Norcross was born in the Kootenay area; primarily lived and worked in the mines of British Columbia; and, ultimately, died in the Kootenay area searching for one of the mines he so loved. He was born in a Granite Siding homestead and began his mining career at age 16. He travelled throughout BC, working in approximately 50 mines. He was closely associated with the Chamber of Mines of Eastern BC and was widely recognized for his knowledge of mining in BC. His obituary noted that with his death, a vital link to the oral history of mining has been lost. But his knowledge of mining has not been lost; it exists here in the archives in his lovingly depicted scenes of mining. The Norcross collection is a wonderful set of drawings, created by an unknown artist who sought to document what he knew about the early years of mining in British Columbia.

When the Webster collection was transferred over to the BC Archives, a determination was made as to which episodes should have priority preservation. As this institution is primarily a holder of Government records, it seemed obvious to focus first and foremost on members of various levels of government.

A viewing of the top picks confirms this supposition. Premiers, Prime Ministers, Leaders of the opposition, mayors, opposition critics, ministers of the crown, and First nations leaders dominate the list.

A quick check shows that of the first 350 shows identified as important, over 200 were shows with political leaders both federal, provincial, first nations and municipal. Many of the rest were shows with people representing special interests trying to influence government with issues such as the environment, special needs, First Nations, unions, business interests, farming, prison reform, mental health, dominating that list.

It was only later that other shows were identified. Shows with authors, musicians, and topics of the day were all identified. We even discovered a person promoting the benefits of cod liver oil!

Now that about three quarters of the shows have been digitized, very little has disappeared through the cracks.

All these decisions were made based on various content lists that were provided with the collection.

Of course, not all shows were identified, and these were described in the listings as “unknown content.”

One of the final sweeps we did was to collect a large number of these undescribed shows and have them digitized as well. One of these episodes stood out.

As Dave Barrett prepared to leave the legislature, Jack Webster had what can best be described as an “exit interview.”

Luckily we had enough special funding to make the decision to have a look at this unknown content to see what was there.

Otherwise we may never have known that this conversation took place.

As we mourn his death, please enjoy this interview.

And remember the Archival mantra. Identify, describe, record!

Start of interview. Link

Dave Barrett’s view of his major achievements. Link

The humour clips Link

As we embrace the festive season, I find myself looking at the faces of young children and families as they discover the magic of Christmas. I see the joy and excitement they feel, and wish I could experience Christmas once more through a child’s eyes. Many of us try to capture the excitement in photographs and videos that we share with family and friends through social media.

In years past, these celebrations would have been captured in 16 mm or 8 mm home movies, some of which survive as treasured family artifacts. Some of these films may find their way into archives where they can be safely preserved for the enjoyment of future generations. I hope families will preserve today’s digital memories as they once preserved film footage.

Paul W. Billwiller was a mining engineer who lived and worked in Britannia Beach, BC. We are lucky to have his home movies in the BC Archives collection, especially because they include footage of a series of Christmas celebrations spanning the years 1946-1953. I would think this type of footage is relatively rare—the same annual event being filmed over several years with the same young boy. This video clip of edited excerpts from the home movies begins with young John Billwiller’s first Christmas in 1946. The family is enjoying their celebration and the new baby is propped up in a chair, surrounded by new toys and showered with attention. I suspect that this was the quietest Christmas for this family for a number of years! We see signs of the affluence of the post-war years, but also the relatively modest gifts that the family members receive: the new mother’s sweater held up for display, and (likely) a grandmother’s bottle of eau de toilette. There are shots of the tree, the festive dinner table resplendent with a golden turkey, and the suit jackets and ties worn by the men.

Three years later, it’s Christmas 1949, and we can revisit a toddler’s pleasure and excitement in opening the gaily wrapped gifts. (Oops, what happens here with John’s toy car?) By 1950, John is considerably more excited by the gift opening. He’s a young lad now—did you notice the smaller red table and child-sized chair? I wonder if John plays at this table when it isn’t holding Christmas presents. The train set must have been the earnest wish of many a young child; his has sliding doors on one car. John is fascinated as he watches the train travel along the track. But wait? Is this John’s father playing with the controls? Come on now, Dad, surely John gets a turn!

I think the pinnacle of holiday excitement occurs during Christmas 1953. John looks so excited that he doesn’t know which present to open first. He’s all smiles as he plays with some sort of pellet gun. And look at this—a set of junior carpentry tools, another much-wished-for gift. There are more gifts this year, including the requisite western cowboy’s holster and six-guns, a toy airplane, and a fancy pen. Yet another holiday dinner with the turkey as the guest of honour, escorted proudly to the table by Mother. And remember those festive paper hats—not too close to the candle flame, John!

We’re fortunate to have this material in our collection, preserved with care and attention, ready for future generations to access. It is a window to another time—one that is long past, but still able to evoke memories of our own family celebrations.

Home movies were special; they were different from the digital footage you shoot on your cell phone. The film was a finite resource. A reel of 8 mm film provided fifty feet, or about four minutes running time. The cost of film and processing placed certain restraints on amateur filmmakers, meaning that they would need to carefully plan out what they intended to capture on film. I think it resulted in home movies that were more tightly focused on relevant subjects. You can see that in several of the Billwiller clips—a shot of the tree, long enough to see it but not lingering, shots of gift opening, and of the turkey.

Free of the constraints imposed by the cost of materials and processing, today’s digital movies of family events, often shot on cell phones, seem more rambling and lacking in narrative focus. They don’t tell a story in the same way that a good film does. And, more worryingly, I wonder if today’s digital artifacts are treated differently than physical film. Countless families have stored reels of film for many decades, but how many people keep an old cell phone in a trunk or box in the attic, or migrate its contents to a hard drive? And even if the digital memories are kept, will they always be accessible? A piece of film, even if damaged, can still be held up to the light, and images appear. A digital file needs the right software and hardware to make it accessible. I am not arguing for film versus digital; I just think we should consider how we want to preserve our digital memories. Paul Billwiller’s footage of his son John’s very first Christmas in 1946 is now 71 years old. It tells us a lot about families, and celebrations, and culture. In 2088, will you be able to access your digital memories to remember those long-ago celebrations?

The Victoria Eaton Centre was built in 1989.

One of the conditions of construction was the promise to maintain the facades of the various buildings that were demolished to make way for the mall.

An example of this is located on the corner of Fort and Broad Street, where the Victoria Times Newspaper had their printing office. Next to it is the Winch building where I remember Eaton’s had a side entrance to their store.

One of the final holdouts was the McDonald’s Restaurant on Douglas Street. It was eventually relocated one block north on the corner of Douglas and View streets. A section of the closed Woolworths store was carved out to create the restaurant. The rest of the building was remodeled to house the Chapters book store.

As part of the reconstruction, eleven architectural elements were added to the building’s View Street façade.

Why were they placed there?

To find the answer, let’s look at the history of the north west corner of Fort and Douglas Street.

The best places to look for the answer are the Victoria fire insurance maps, the Victoria City directories and some historic photographs.

The 1911 Fire Insurance map Vol 1 shows the area on page 7.

Most of the block is developed, including the Times and Winch buildings on Fort Street.

On Douglas Street, The Royal Dairy is half way down the Block, next to the Victoria Theatre building which extends to View Street. There is a note on the plan that David Spencer Dry Goods operates in the north half of the block around and above the theatre.

The land on the corner of Fort and Douglas between the dairy and the Winch building contains several one story buildings and another more substantial one story building right on the corner.

The city directories add further information.

The 1912 city directory lists several tenants in the Times building.

The Winch building (640 Fort) appears to be empty, but

James Waites, locksmith (644 Fort)

Edward Jackson, shoemaker 646 Fort) and

Duncan Campbell, druggist (650 Fort) are listed.

Douglas Street is occupied by

Duncan Campbell, druggist (1100 Douglas) Note the double address for the corner

J H Tomlinsons, real estate (1106 Douglas)

Royal Dairy (1110 Douglas) and

Victoria Theatre (1112 and 1116 Douglas)

The Dairy is in a separate building. The theatre has it’s own separate entrances.

The entrance to Spencer’s store is around the corner at 637 View Street and 1119 Broad Street, both near that corner.

By 1920 it appears that the Theatre has closed and Spencer’s has taken over the theatre’s two Douglas Street entrances.

United Coop Association (1104 Douglas)

Dunfords Limited (1106 Douglas)

Royal Dairy (1110 Douglas)

David Spencer Ltd (1112 and 1116 Douglas)

On Fort Street, the Winch building is occupied by 28 tenants

The Square Deal Hardware company occupies the corner building (650 Fort)

The United Coop is wrapped around it at 646 Fort and 1104 Douglas.

The Shoemaker is now at 648 Fort

By 1929 the Winch building is renamed by its major tenant, The Christy Hall building (640 Fort) and The Square Deal Hardware Company is still in operation.

Douglas Street is occupied by

Madeline Silk Shops (1102 Douglas)

VH Watchorn (1104 Douglas)

Gordon Ellis Ltd (1104 Douglas)

Leather Goods Store (1106 Douglas)

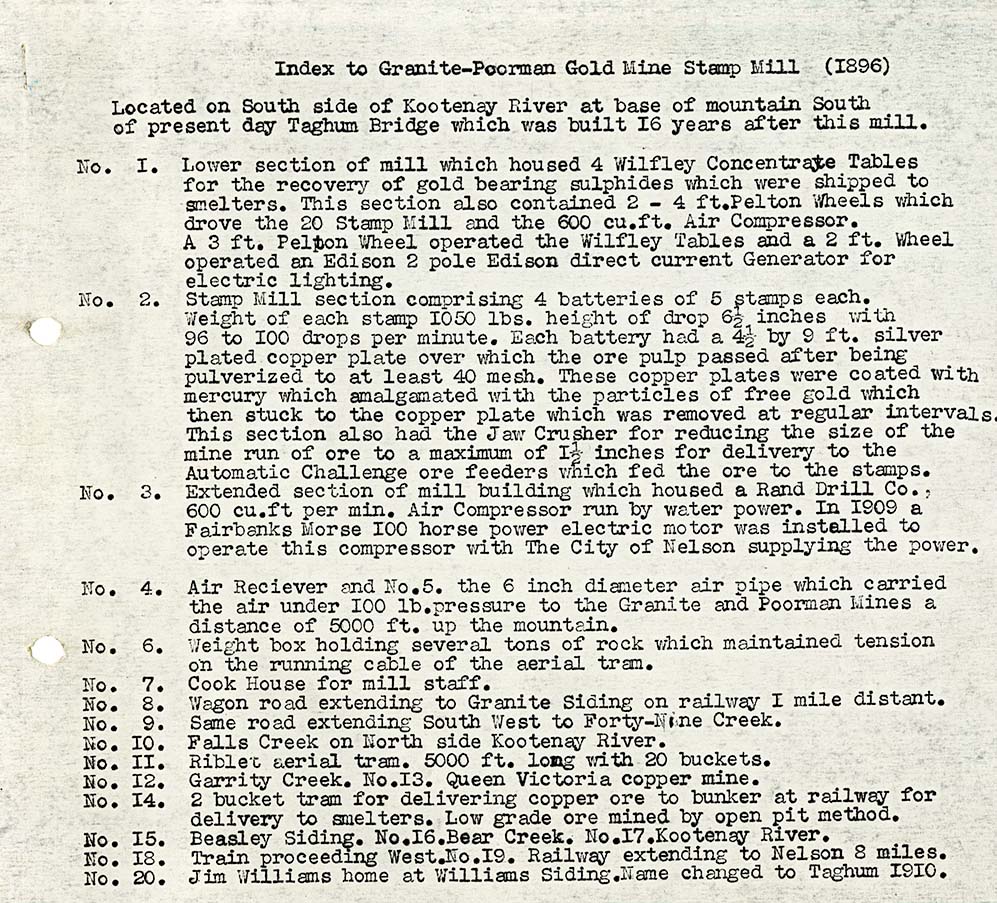

Fletcher Brothers (a music store) (1110 Douglas) and

David Spencer (1112 Douglas), reduced now to a single address.

By 1940 more changes are made to the street addresses, reflecting more closely what they were when the mall was built in 1989.

In 1930, the buildings on the corner are replaced by the Kresge Department Store (1930, archt. G.A. McElroy of Windsor)

The new building has a unique Douglas Street address for the SS Kresge Company on the ground floor and a separate address for the upstairs tenants. (1100 and 1104)

Part of the new building includes Sobie Silk shops at 1106 and

Norman Cull optometrist is at 1108

The Dairy building now has two tenants

Sally Shop (1126) and

Fletcher Brothers (1130)

The main entrance to Spencer’s is now 1150 Douglas, which Eaton’s maintained as their store address and is now the street address for the present mall.

Across the Street are various businesses including

Film shop, photograph developer at 1107

Kelways Black Horse Café (1111)

George Straith men’s clothing store (1117)

This photograph shows Douglas Street during the mid 1940’s.

This detail shows the business signs from the buildings across the street from the Spencer’s store. You can make out some of the street signs for the businesses mentioned earlier.

This detail shows the entrance to Spencer’s Store and the Woolworth building in the background.

And at the very bottom left of the photograph is this design detail.

One of the tricks used in early twentieth century building design was to make the front of your building look taller than it really was.

This seems to be the case here.

Notice how the roofline of the Kresge building seems to match up with the old dairy building next door, But the Fletcher music sign is still visible in this photograph.

A similar example can be seen for what is now 1222 Douglas Street.

This picture shows the Kresge building more clearly. It very much is attempting to hide the fact that this building is only two stories tall by trying to be nearly as tall as the three story building beside it.

And look! There are those design elements used to rebuild the restaurant mentioned earlier.

All 20 of them.

Over time, The Kresge’s store became a Marks and Spencer’s.

And the McDonald’s? It moved into the former Dairy building that the Fletcher’s Music store and the Sally shop had occupied.

So the design elements on the new restaurant are actually from the building beside it.

As an aside, if you ever visit the mall have a look at the front entrance. Or go out on the food court veranda and explore there.

There are several images in the Archives collection that I used in the article, or noticed while researching this article

Looking towards the new restaurant

1130 Douglas Street (Day and night)

The Royal Dairy sign

Vernon Hotel (the Woolworth building)

The Woolworth store

View Street pre Kresge’s

Douglas Street taken south of Fort Street

Winter scene with Ritz Hotel

In passing

Guess where this is?

It moved

To compete with this?

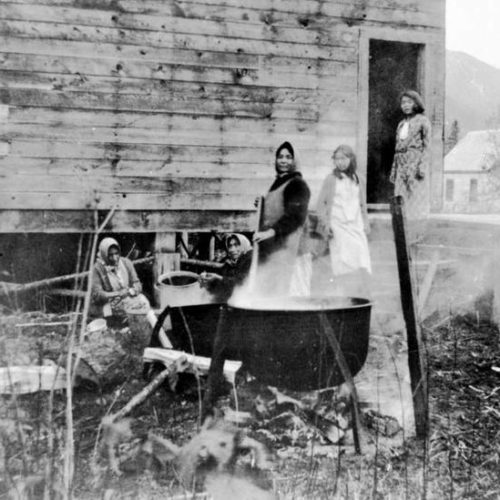

The BC Packers film Salmon for Food (1945), directed by Oscar C. Burritt for Vancouver Motion Pictures Ltd., includes wonderful footage of female cannery workers. This is an industrial film, a sponsored film created for an external audience but not intended for theatrical release. The segment dealing with the female workers has a different atmosphere. There is more of the feel of documentary film, informing the viewer of the nature of the working lives of these women.

In order to keep the film clip to a reasonable length, I have chosen not to include footage of the male workers at the cannery. The faces of the men at work are primarily turned away from the camera, which focuses more on their hands. This has the effect of emphasizing the tasks and de-personalizing the male workers. The camera moves in more tightly on the faces of the women, highlighting their facial expressions; their hands are busy at work or gesturing as the women talk amongst themselves. We are invited to share their world of work in the salmon cannery. I think the feeling of engagement here moves Salmon for Food from strictly industrial film to social documentary.

I like to search for industrial film footage of women at work because women’s work generally was less likely to be documented; therefore footage of it is rarer. I’ve blogged previously about scenes of female laundry workers in Kamloops. That footage is quite different from the footage in Salmon for Food. The footage from White Way Laundry & Dry Cleaners depicts women working as individuals at separate machines, while the salmon cannery workers cluster in groups as they work together on the production line, and as they socialize. The camera work in the cannery film personalizes the workers, and brings the scene to life.

Unusually for an industrial film, this segment depicts the cannery facilities that create an environment attractive to women: a medical clinic with a nurse; a tea room for those restorative afternoon breaks; and on-site housing. It’s likely that these facilities were intended to attract and to retain the female workforce.

I expect this film would have been used primarily as a marketing tool for the salmon industry–but it survives today as a record of women’s role as labour in the industry. Curiously, however, the female cannery workers in this film all appear to be Caucasian. Historically, there were also First Nations and Asian women working in the canneries. Why are women of colour not included in this film? Was it a deliberate choice by the filmmakers or sponsors? Seventy years after the film was made, one can only speculate.

Digital frame grabs from Salmon for Food.

CETA 1972 style post

While working with archival documents it is always of interest to look at the other side of the page.

In today’s example, A person needed to publish several legal notices in the local paper.

Luckily, the entire newspaper page was submitted.

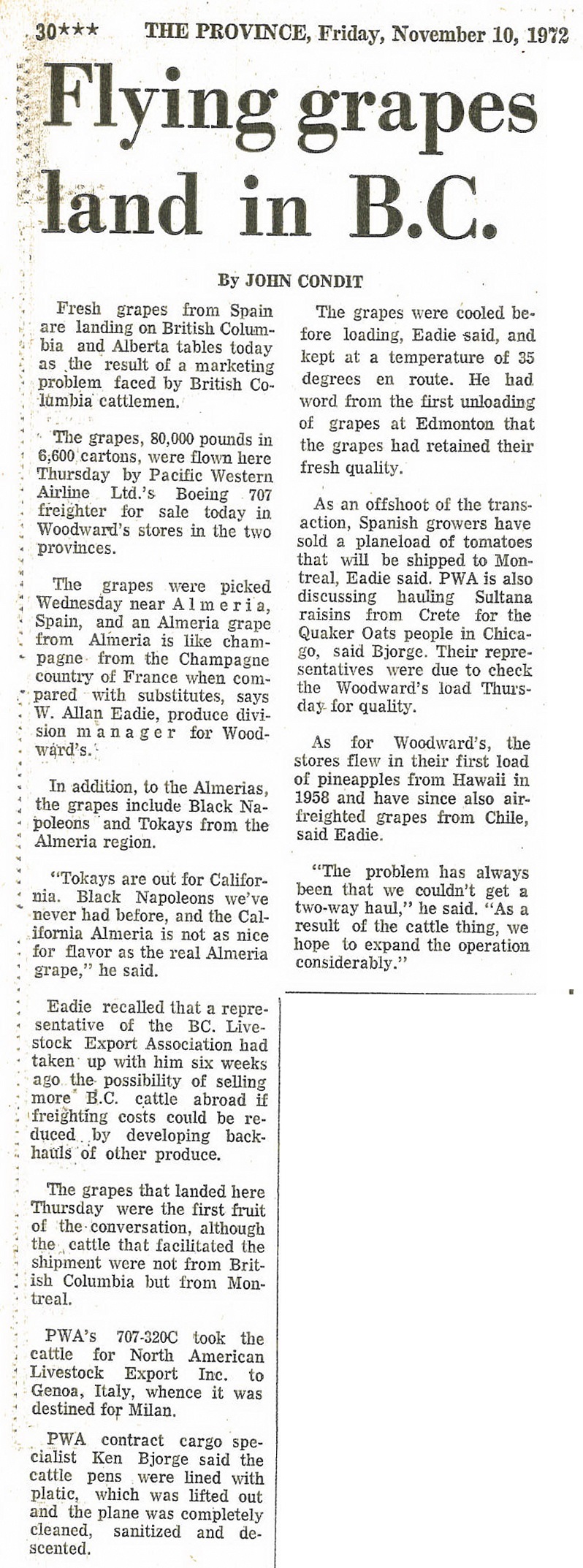

The following article appeared on the back of the page (The Province [Vancouver], Friday, 10 November, 1972.)

It describes how Pacific Western Airlines was able to ship live beef to Europe, because its cargo plane could return with a cargo of grapes which were now available throughout BC and Alberta.

The article also explains how the plane was cleaned, presumably before the grapes were loaded on to the plane.

The Wikipedia page for PWA mentions the following:

Boeing 707 equipment was added to the fleet in 1967… The addition of a cargo model Boeing 707 meant that livestock and perishables could now be carried all over the world, and the name Pacific Western became synonymous with “World Air Cargo”. The company aircraft visited more than 90 countries during this period of time.

Pacific Western operated a worldwide Boeing 707 cargo and passenger charter program until the last aircraft was sold in 1979.

This is in the era where container shipping was beginning its world wide adoption.

Air cargo was expanding during this time as well, when “Boeing launched the four engine 747, the first wide-body aircraft” in 1968.

As the newspaper report explains, transportation of people and goods only makes sense if the airplane is loaded to maximum capacity at all times.

This was the thinking behind the Triangular trading system of the 19th century.

Moving people extended this thinking to modern day hub airports such as Toronto Pearson, London Heathrow and Dubai UAE.

Even today with airplanes that can travel half way around the world, the take off and landing locations are the national hub airports.

Air cargo has undergone the same thinking.

In the 1972 news report, it only made sense to Pacific Western Airlines to undertake this one-off trip once the entire route was fully booked.

The article goes on to describe how the airline was looking for other opportunities. They recognized the potential, but the tipping point (the development of an airport hub for cargo) had not yet arrived.