Digital Preservation

- BC Place Stadium

- Canada Place – the cruise ship terminal

- Skytrain

- Redevelopment of False Creek – the Expo 86 site

Sometimes the most mundane tasks can lead to the most interesting discoveries.

One of those mundane but essential tasks is the compilation of inventories. My department wants to ensure that all of the colour transparencies and slides of our Paintings, Drawings, and Prints (PDP) collection have been scanned, uploaded and attached to their online descriptions in AtoM. We need an inventory to assist with this. It’s a pretty straightforward process: I look at the transparencies, list them by PDP number, determine if the image is already available in our digital repository, check that a description exists in AtoM, and see if a scan of the image already appears online. I have a good eye for detail, and I find a number of anomalies I’ll need to straighten out.

Then I lift a transparency to the light and I see a colourful image that reminds me of the folk art of Maud Lewis. I pick up another, and it is more of the same. These images I am holding in my hands are colourful, and with one or two there is a sense of whimsy. I think it is the sense of motion and the relationship between space and perspective that reminds me of Lewis’s work. Taken as a group, they are very detailed and technical–yet they are not technical drawings.

These transparencies make me eager to see the originals. A colleague and I go into the PDP vault and locate the container. We find that the colours in the originals are far brighter than those in the transparencies; they appear to be drawn in pencil crayon. The subject of all of the drawings is mining in British Columbia. We’re entranced by the originals—the passion the artist has for his subject is clearly evident.

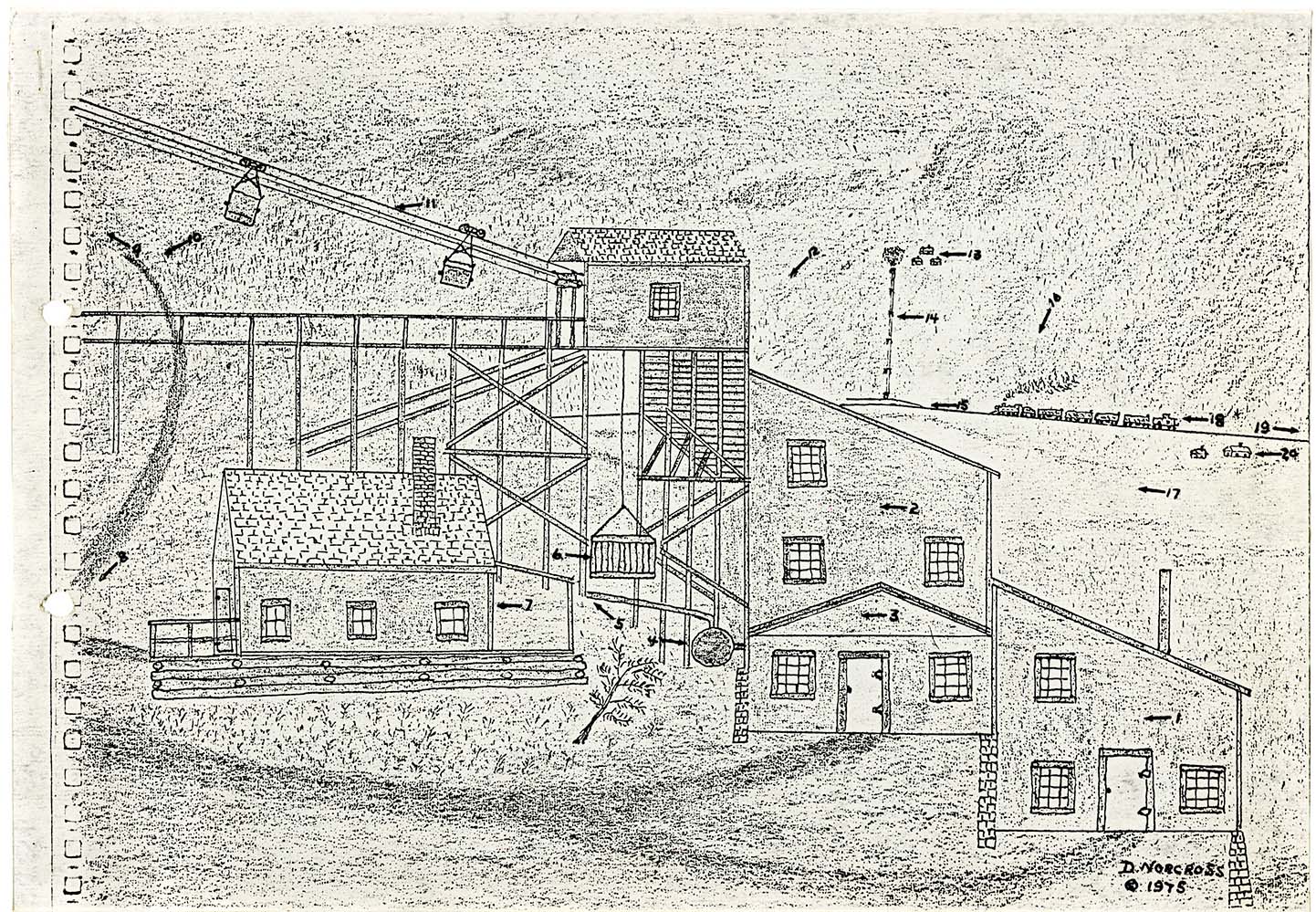

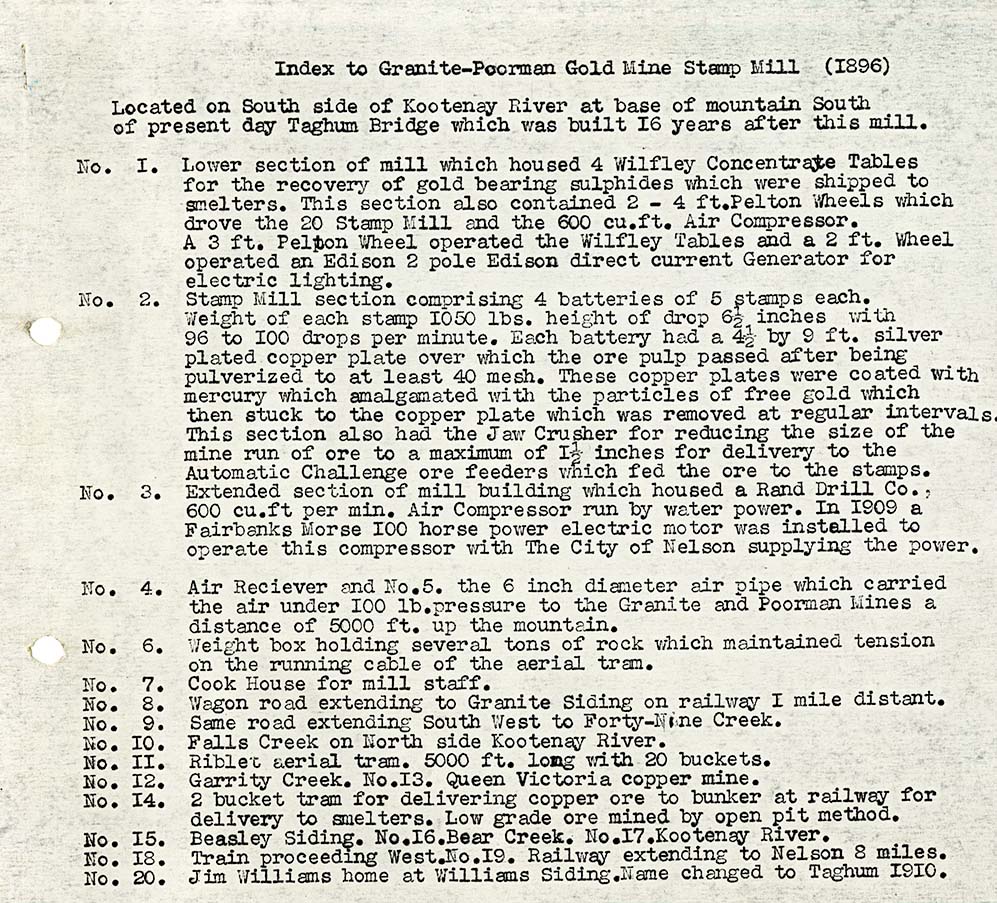

While compiling his memoirs, David Henry Norcross (1901-1980) gathered his drawings of early mining into a collection he named “Recollections 1975.” The container holds more than the colour drawings. Within a brown binder anchored by a metal clip, there is photocopied material meant to act as an index or finding aid to the images. This material includes copies of the drawings and written commentary to accompany each image. This includes description of machinery, transport, mining tools, miners, mine sites, and history. On the copies of the drawings, Norcross has numbered certain points, which then correspond to points in the commentary. Unfortunately, the paper appears to be from an earlier form of photocopying, and the ink used on it has already faded. I’m glad that I’ve discovered this in time, and I make a digital preservation surrogate. Now, at least, we will have a stable preservation copy of the information provided by Norcross.

The man who made these drawings also wrote “I am not an artist” in the introduction to his material. I think that simple statement expresses one rationale for our PDP collection. It is a documentary art collection, where the pieces are acquired and preserved because of the visual record they provide of British Columbia’s past. This isn’t about pieces of fine art; it is about documenting specific times and places, people and activities.

Norcross was born in the Kootenay area; primarily lived and worked in the mines of British Columbia; and, ultimately, died in the Kootenay area searching for one of the mines he so loved. He was born in a Granite Siding homestead and began his mining career at age 16. He travelled throughout BC, working in approximately 50 mines. He was closely associated with the Chamber of Mines of Eastern BC and was widely recognized for his knowledge of mining in BC. His obituary noted that with his death, a vital link to the oral history of mining has been lost. But his knowledge of mining has not been lost; it exists here in the archives in his lovingly depicted scenes of mining. The Norcross collection is a wonderful set of drawings, created by an unknown artist who sought to document what he knew about the early years of mining in British Columbia.

When the Webster collection was transferred over to the BC Archives, a determination was made as to which episodes should have priority preservation. As this institution is primarily a holder of Government records, it seemed obvious to focus first and foremost on members of various levels of government.

A viewing of the top picks confirms this supposition. Premiers, Prime Ministers, Leaders of the opposition, mayors, opposition critics, ministers of the crown, and First nations leaders dominate the list.

A quick check shows that of the first 350 shows identified as important, over 200 were shows with political leaders both federal, provincial, first nations and municipal. Many of the rest were shows with people representing special interests trying to influence government with issues such as the environment, special needs, First Nations, unions, business interests, farming, prison reform, mental health, dominating that list.

It was only later that other shows were identified. Shows with authors, musicians, and topics of the day were all identified. We even discovered a person promoting the benefits of cod liver oil!

Now that about three quarters of the shows have been digitized, very little has disappeared through the cracks.

All these decisions were made based on various content lists that were provided with the collection.

Of course, not all shows were identified, and these were described in the listings as “unknown content.”

One of the final sweeps we did was to collect a large number of these undescribed shows and have them digitized as well. One of these episodes stood out.

As Dave Barrett prepared to leave the legislature, Jack Webster had what can best be described as an “exit interview.”

Luckily we had enough special funding to make the decision to have a look at this unknown content to see what was there.

Otherwise we may never have known that this conversation took place.

As we mourn his death, please enjoy this interview.

And remember the Archival mantra. Identify, describe, record!

Start of interview. Link

Dave Barrett’s view of his major achievements. Link

The humour clips Link

As we embrace the festive season, I find myself looking at the faces of young children and families as they discover the magic of Christmas. I see the joy and excitement they feel, and wish I could experience Christmas once more through a child’s eyes. Many of us try to capture the excitement in photographs and videos that we share with family and friends through social media.

In years past, these celebrations would have been captured in 16 mm or 8 mm home movies, some of which survive as treasured family artifacts. Some of these films may find their way into archives where they can be safely preserved for the enjoyment of future generations. I hope families will preserve today’s digital memories as they once preserved film footage.

Paul W. Billwiller was a mining engineer who lived and worked in Britannia Beach, BC. We are lucky to have his home movies in the BC Archives collection, especially because they include footage of a series of Christmas celebrations spanning the years 1946-1953. I would think this type of footage is relatively rare—the same annual event being filmed over several years with the same young boy. This video clip of edited excerpts from the home movies begins with young John Billwiller’s first Christmas in 1946. The family is enjoying their celebration and the new baby is propped up in a chair, surrounded by new toys and showered with attention. I suspect that this was the quietest Christmas for this family for a number of years! We see signs of the affluence of the post-war years, but also the relatively modest gifts that the family members receive: the new mother’s sweater held up for display, and (likely) a grandmother’s bottle of eau de toilette. There are shots of the tree, the festive dinner table resplendent with a golden turkey, and the suit jackets and ties worn by the men.

Three years later, it’s Christmas 1949, and we can revisit a toddler’s pleasure and excitement in opening the gaily wrapped gifts. (Oops, what happens here with John’s toy car?) By 1950, John is considerably more excited by the gift opening. He’s a young lad now—did you notice the smaller red table and child-sized chair? I wonder if John plays at this table when it isn’t holding Christmas presents. The train set must have been the earnest wish of many a young child; his has sliding doors on one car. John is fascinated as he watches the train travel along the track. But wait? Is this John’s father playing with the controls? Come on now, Dad, surely John gets a turn!

I think the pinnacle of holiday excitement occurs during Christmas 1953. John looks so excited that he doesn’t know which present to open first. He’s all smiles as he plays with some sort of pellet gun. And look at this—a set of junior carpentry tools, another much-wished-for gift. There are more gifts this year, including the requisite western cowboy’s holster and six-guns, a toy airplane, and a fancy pen. Yet another holiday dinner with the turkey as the guest of honour, escorted proudly to the table by Mother. And remember those festive paper hats—not too close to the candle flame, John!

We’re fortunate to have this material in our collection, preserved with care and attention, ready for future generations to access. It is a window to another time—one that is long past, but still able to evoke memories of our own family celebrations.

Home movies were special; they were different from the digital footage you shoot on your cell phone. The film was a finite resource. A reel of 8 mm film provided fifty feet, or about four minutes running time. The cost of film and processing placed certain restraints on amateur filmmakers, meaning that they would need to carefully plan out what they intended to capture on film. I think it resulted in home movies that were more tightly focused on relevant subjects. You can see that in several of the Billwiller clips—a shot of the tree, long enough to see it but not lingering, shots of gift opening, and of the turkey.

Free of the constraints imposed by the cost of materials and processing, today’s digital movies of family events, often shot on cell phones, seem more rambling and lacking in narrative focus. They don’t tell a story in the same way that a good film does. And, more worryingly, I wonder if today’s digital artifacts are treated differently than physical film. Countless families have stored reels of film for many decades, but how many people keep an old cell phone in a trunk or box in the attic, or migrate its contents to a hard drive? And even if the digital memories are kept, will they always be accessible? A piece of film, even if damaged, can still be held up to the light, and images appear. A digital file needs the right software and hardware to make it accessible. I am not arguing for film versus digital; I just think we should consider how we want to preserve our digital memories. Paul Billwiller’s footage of his son John’s very first Christmas in 1946 is now 71 years old. It tells us a lot about families, and celebrations, and culture. In 2088, will you be able to access your digital memories to remember those long-ago celebrations?

The Victoria Eaton Centre was built in 1989.

One of the conditions of construction was the promise to maintain the facades of the various buildings that were demolished to make way for the mall.

An example of this is located on the corner of Fort and Broad Street, where the Victoria Times Newspaper had their printing office. Next to it is the Winch building where I remember Eaton’s had a side entrance to their store.

One of the final holdouts was the McDonald’s Restaurant on Douglas Street. It was eventually relocated one block north on the corner of Douglas and View streets. A section of the closed Woolworths store was carved out to create the restaurant. The rest of the building was remodeled to house the Chapters book store.

As part of the reconstruction, eleven architectural elements were added to the building’s View Street façade.

Why were they placed there?

To find the answer, let’s look at the history of the north west corner of Fort and Douglas Street.

The best places to look for the answer are the Victoria fire insurance maps, the Victoria City directories and some historic photographs.

The 1911 Fire Insurance map Vol 1 shows the area on page 7.

Most of the block is developed, including the Times and Winch buildings on Fort Street.

On Douglas Street, The Royal Dairy is half way down the Block, next to the Victoria Theatre building which extends to View Street. There is a note on the plan that David Spencer Dry Goods operates in the north half of the block around and above the theatre.

The land on the corner of Fort and Douglas between the dairy and the Winch building contains several one story buildings and another more substantial one story building right on the corner.

The city directories add further information.

The 1912 city directory lists several tenants in the Times building.

The Winch building (640 Fort) appears to be empty, but

James Waites, locksmith (644 Fort)

Edward Jackson, shoemaker 646 Fort) and

Duncan Campbell, druggist (650 Fort) are listed.

Douglas Street is occupied by

Duncan Campbell, druggist (1100 Douglas) Note the double address for the corner

J H Tomlinsons, real estate (1106 Douglas)

Royal Dairy (1110 Douglas) and

Victoria Theatre (1112 and 1116 Douglas)

The Dairy is in a separate building. The theatre has it’s own separate entrances.

The entrance to Spencer’s store is around the corner at 637 View Street and 1119 Broad Street, both near that corner.

By 1920 it appears that the Theatre has closed and Spencer’s has taken over the theatre’s two Douglas Street entrances.

United Coop Association (1104 Douglas)

Dunfords Limited (1106 Douglas)

Royal Dairy (1110 Douglas)

David Spencer Ltd (1112 and 1116 Douglas)

On Fort Street, the Winch building is occupied by 28 tenants

The Square Deal Hardware company occupies the corner building (650 Fort)

The United Coop is wrapped around it at 646 Fort and 1104 Douglas.

The Shoemaker is now at 648 Fort

By 1929 the Winch building is renamed by its major tenant, The Christy Hall building (640 Fort) and The Square Deal Hardware Company is still in operation.

Douglas Street is occupied by

Madeline Silk Shops (1102 Douglas)

VH Watchorn (1104 Douglas)

Gordon Ellis Ltd (1104 Douglas)

Leather Goods Store (1106 Douglas)

Fletcher Brothers (a music store) (1110 Douglas) and

David Spencer (1112 Douglas), reduced now to a single address.

By 1940 more changes are made to the street addresses, reflecting more closely what they were when the mall was built in 1989.

In 1930, the buildings on the corner are replaced by the Kresge Department Store (1930, archt. G.A. McElroy of Windsor)

The new building has a unique Douglas Street address for the SS Kresge Company on the ground floor and a separate address for the upstairs tenants. (1100 and 1104)

Part of the new building includes Sobie Silk shops at 1106 and

Norman Cull optometrist is at 1108

The Dairy building now has two tenants

Sally Shop (1126) and

Fletcher Brothers (1130)

The main entrance to Spencer’s is now 1150 Douglas, which Eaton’s maintained as their store address and is now the street address for the present mall.

Across the Street are various businesses including

Film shop, photograph developer at 1107

Kelways Black Horse Café (1111)

George Straith men’s clothing store (1117)

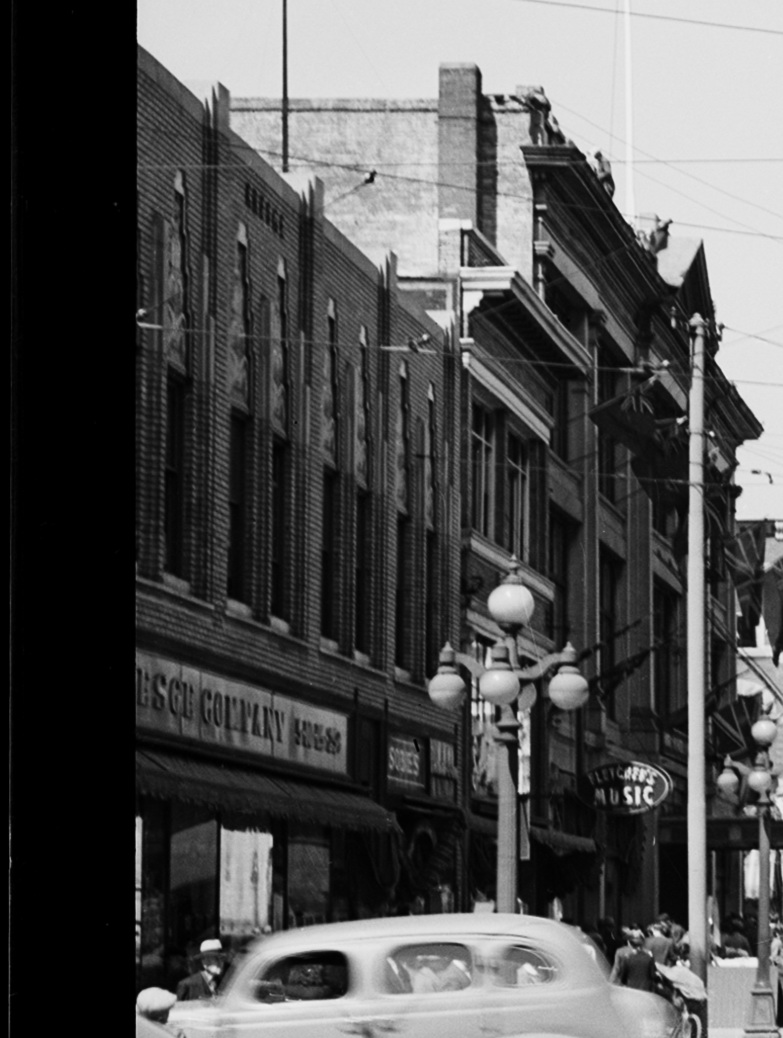

This photograph shows Douglas Street during the mid 1940’s.

This detail shows the business signs from the buildings across the street from the Spencer’s store. You can make out some of the street signs for the businesses mentioned earlier.

This detail shows the entrance to Spencer’s Store and the Woolworth building in the background.

And at the very bottom left of the photograph is this design detail.

One of the tricks used in early twentieth century building design was to make the front of your building look taller than it really was.

This seems to be the case here.

Notice how the roofline of the Kresge building seems to match up with the old dairy building next door, But the Fletcher music sign is still visible in this photograph.

A similar example can be seen for what is now 1222 Douglas Street.

This picture shows the Kresge building more clearly. It very much is attempting to hide the fact that this building is only two stories tall by trying to be nearly as tall as the three story building beside it.

And look! There are those design elements used to rebuild the restaurant mentioned earlier.

All 20 of them.

Over time, The Kresge’s store became a Marks and Spencer’s.

And the McDonald’s? It moved into the former Dairy building that the Fletcher’s Music store and the Sally shop had occupied.

So the design elements on the new restaurant are actually from the building beside it.

As an aside, if you ever visit the mall have a look at the front entrance. Or go out on the food court veranda and explore there.

There are several images in the Archives collection that I used in the article, or noticed while researching this article

Looking towards the new restaurant

1130 Douglas Street (Day and night)

The Royal Dairy sign

Vernon Hotel (the Woolworth building)

The Woolworth store

View Street pre Kresge’s

Douglas Street taken south of Fort Street

Winter scene with Ritz Hotel

In passing

Guess where this is?

It moved

To compete with this?

The BC Packers film Salmon for Food (1945), directed by Oscar C. Burritt for Vancouver Motion Pictures Ltd., includes wonderful footage of female cannery workers. This is an industrial film, a sponsored film created for an external audience but not intended for theatrical release. The segment dealing with the female workers has a different atmosphere. There is more of the feel of documentary film, informing the viewer of the nature of the working lives of these women.

In order to keep the film clip to a reasonable length, I have chosen not to include footage of the male workers at the cannery. The faces of the men at work are primarily turned away from the camera, which focuses more on their hands. This has the effect of emphasizing the tasks and de-personalizing the male workers. The camera moves in more tightly on the faces of the women, highlighting their facial expressions; their hands are busy at work or gesturing as the women talk amongst themselves. We are invited to share their world of work in the salmon cannery. I think the feeling of engagement here moves Salmon for Food from strictly industrial film to social documentary.

I like to search for industrial film footage of women at work because women’s work generally was less likely to be documented; therefore footage of it is rarer. I’ve blogged previously about scenes of female laundry workers in Kamloops. That footage is quite different from the footage in Salmon for Food. The footage from White Way Laundry & Dry Cleaners depicts women working as individuals at separate machines, while the salmon cannery workers cluster in groups as they work together on the production line, and as they socialize. The camera work in the cannery film personalizes the workers, and brings the scene to life.

Unusually for an industrial film, this segment depicts the cannery facilities that create an environment attractive to women: a medical clinic with a nurse; a tea room for those restorative afternoon breaks; and on-site housing. It’s likely that these facilities were intended to attract and to retain the female workforce.

I expect this film would have been used primarily as a marketing tool for the salmon industry–but it survives today as a record of women’s role as labour in the industry. Curiously, however, the female cannery workers in this film all appear to be Caucasian. Historically, there were also First Nations and Asian women working in the canneries. Why are women of colour not included in this film? Was it a deliberate choice by the filmmakers or sponsors? Seventy years after the film was made, one can only speculate.

Digital frame grabs from Salmon for Food.

Expo 86 opened its doors to the world on 02 May, 1986.

Leading up to the World Fair, several large infrastructure projects were proposed and planned for, so that they would be open and useable by the public by the time the fair opened.

These projects included

These projects were discussed on the Webster Show.

Of course politics was involved, as the mayor defended his vision of what Vancouver would look like, as it celebrated the hundredth anniversary of its founding.

Redevelopment of False Creek was a major issue – BC Architect Arthur Erickson and the director of planning for BC Place, David Padmore discuss the Expo 86 site plans.

Here is the interview of a member of the BC Place planning committee.

Sky train was a region wide issue.

This episode shows the proposed route of the LRT as Steve Wyatt drives the streets of Vancouver, trying to get as close to the proposed route as possible.

Bear in mind that the route used existing railway rights of way for the majority (if not all) of the line.

There are several versions of this. The final one was slowed down somewhat so you can see the surrounding city a little more easily.

For the unedited show see this Link.

Canada Place – the cruise ship terminal. Webster goes on a fly about/ walk about

BCTV was a major sponsor and broadcast daily from the Expo grounds.

Here is part of the hype, when some of the pieces get lost.

Counting Down to opening day

And after the exhibition

The auction

And distributing the wealth

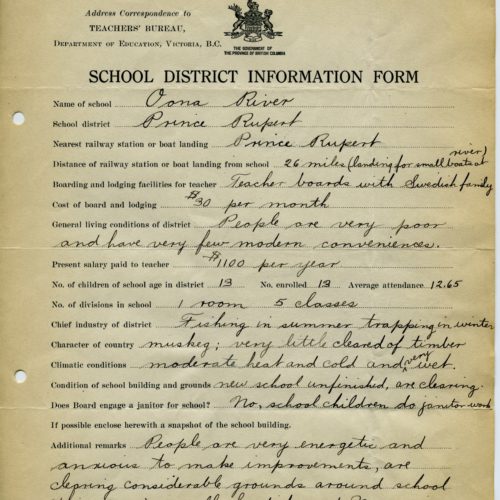

One of my tasks as a Digital Access Technician is to identify and propose small digitization projects. Imagine browsing in the archives stack areas, surrounded by all manner of storage containers. As I walk through the stacks, I am thinking about my experience in the reference room, and recalling which records groups were most frequently consulted. What kinds of questions did people have, and what records did I use to answer those inquiries?

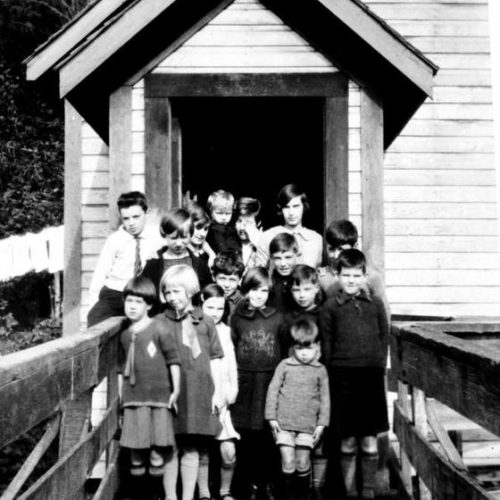

I find myself pulling a box of GR-0461, Teachers Bureau records off the shelf and moving to a table to browse its contents. We often receive requests for information about specific BC schools, and about their teachers. These records are interesting for what they reveal about the history of education, and as records of rural life in British Columbia. They are also valuable in family and genealogical research. Young men and women became teachers and moved to these rural and remote schools. Now their grandchildren and great-grandchildren search for records that might contain a glimpse into the teacher’s world. Public interest is a factor I think about when proposing a digitization project. Not only do I want to draw attention to our records, but I also want the digitized records to be useful to the public. Records that are useful for genealogy research meet a public demand.

The extent of the records is something to consider. I like to keep projects to a reasonable size so they can be completed in a timely manner. This group consists of approximately 1400 pages, and that strikes me as about the right size for a small digitization project. The format of the records is another important consideration. Can I scan them easily myself, without help from our staff photographer? Do they need to be removed from bindings? Will they require conservation prior to scanning? Preparing such records for scanning takes more time and additional staff resources.

GR-0461 consists of two boxes of documents in file folders. That’s a manageable size for a small project. This group consists of forms that were sent to schools, filled out, and returned to the Department of Education. I wonder, “How complete are the forms? What types of questions are asked? Are there any other materials in the files?” This group’s forms are reasonably complete, with questions and answers that I think will interest the public; there are also some photographs of the schools to add interest to primarily textual records. The range of responses and the inclusion of images make me think this would be a good digitization project to suggest.

Before I digitize these records for access, I make sure that there are corresponding online descriptions available. I need a proper descriptive record to attach the digitized images to, and those records are usually created by an archivist. Fortunately, the appropriate level of descriptive work for GR-0461 has already been done in AtoM, and that makes this project more likely to be approved by my manager.

That is the informal process I go through when I consider a candidate for digitization. I think about what will interest researchers, about the extent and condition of the records (to keep the project within a manageable size), and about how much descriptive work will be required in order to provide digital access online. GR-0461 meets all these conditions, and has been added to my list of proposed digitization projects. If all goes well, the forms in GR-0461, Teachers’ Bureau Records, will be online for users to access.

One of the pleasures of working in the archives is the opportunity to pull out a box of records and examine the records inside. It’s a bit like opening a gift from the past. You never know what sort of discoveries or connections await within. When I had a few minutes recently, I sat down with Box 1 of GR-0461, Teachers’ Bureau Records, and browsed through it. In those few minutes, I learned a lot about the conditions faced in some of British Columbia’s rural and assisted schools in the 1920s.

The Teachers’ Bureau acted as an employment exchange by gathering information about the schools and districts, and by conveying information about vacancies and the schools to prospective applicants. The records in GR-0461 consist of School District Information Forms—questionnaires that were distributed to rural school teachers in 1923 and 1928. This set of records is not entirely complete. There were 684 rural and assisted schools in 1923, but only 651 completed forms exist from that year. In 1928, there were 728 schools, but there are only 711 completed forms.

Those who completed and returned the School District Information Forms to the Teachers’ Bureau left a very useful tool for examining working conditions for teachers in the 1920s. The more remote the community, the more likely the teacher was to experience loneliness and isolation. The living conditions at Big Bar Upper School in the school district of Lillooet were described as “Isolated and lonely. Crude pioneer homes. Very little money to be had.”[i] Similar sentiments are expressed by many of the teachers. Living conditions at the Copper Creek Station School were tersely described as “Absent” — a case of “create your own world.” Boarding and lodging options there were “very limited and unattractive.”[ii] Some of the “additional remarks” on the forms indicate the skills necessary for success. “This school requires a strict fearless teacher; and one who is impervious to dismay.”[iii] So wrote the teacher at Big Bar in 1923, Gerald S. Andrews. That name may ring a bell for those familiar with BC history and our archival records—Gerald S. Andrews was later to become the Surveyor General for British Columbia.

Perhaps Dorothy A. Clarke of North Dawson Creek said it best in her additional remarks: “Teachers labor under great difficulties in this country, as the settlers are very poor and they find it exceedingly hard to make a bare living for themselves. Consequently it is really hard to get any money together for school purposes. I do not think it wise to encourage young and inexperienced teachers of either sex to come in here to any of the schools.”[iv] Such were the conditions in the rural and remote schools of British Columbia during the 1920s.

=====

[i] GR-0461, Box 1, File 1.

[ii] GR-0461, Box 1, File 2.

[iii] GR-0461, Box 1, File 1.

[iv] GR-0461, Box 1, File 3.

I really like this film sequence for what it reveals about women’s roles in the paid workforce. So much footage of this period focuses on the work of men. Women, when they are shown, are invariably depicted in the domestic sphere, caring for the needs and the comfort of their families. So it is unusual to have this insight into the world of work outside the home.

This work is obviously physically demanding; these women don’t have desk jobs. They would need to be strong, capable of standing all day operating equipment, and of working in a hot and humid environment. I was struck by how all the female workers wore uniforms to work in the laundry. I wonder if the employees were required to purchase the uniforms or whether they were supplied by their employer.

Vancouver filmmaker Alfred E. Booth (1892-1977) shot footage of various businesses in the Kamloops area. It isn’t clear if these businesses hired him to do this or if he was working on his own initiative—shooting the footage with the hope of being able to sell it to the business owner. Loose strips of title frames attached to this compilation may indicate the titles of proposed or completed films related to this and other footage: “Kamloops – the Hub City of B.C, and on into the Spectacular Clearwater Country”; “Lake and River Fishing for the Sporty Kamloops Trout”; “By Packhorse and Canoe beyond the Scenic North Thompson River”. He may have had a larger project in mind. These segments of footage, including the White Way excerpt have been preserved in the archives as part of the Alfred E. Booth fonds. This sequence is part of the archival compilation reel “[Kamloops] : [footage and out-takes]“.

Each of the recipes is clustered around a common carbohydrate: “Take a can of Clover Leaf Pink Salmon and _____”. You filled in the blank with your choice of carbohydrate — biscuit dough, bread crumbs, pastry, potatoes, rice, cracker crumbs, or macaroni. They are simple recipes with few ingredients, and they rely on processed foods such as canned vegetables, canned shoestring potatoes, and the (infamous) canned cream of mushroom soup.

I find the inclusion of the price per serving instructive. Many of the dishes cost less than 25 cents per serving; the per-serving cost ranges from a low of 9 cents for “Salmon Potato Cakes” to a whopping 28 cents for the “Skillet Supper”. The convenience of canned salmon, and the fact that cans could be stored safely without need for refrigeration, probably made the product attractive to the consumer. I don’t know how many women would have prepared the more elaborate salmon dishes demonstrated in Part 1’s filmed cooking class, but my own experience in the early sixties attests to the fact that middle-class mothers really did make salmon fish cakes and salmon loaf as regular dinner offerings.

The recipes included in this pamphlet are far more practical than those presented onscreen in the film Silver Harvest. The Salmon Potato Cakes, for example, were probably a standard reliable main dish on many Canadian dinner tables. They were quick to prepare and cook, utilized a common leftover (mashed potatoes), and could easily be stretched to accommodate an extra person at supper. In my childhood, they appeared for supper with astonishing regularity. While they weren’t my favourite dish, I knew that there were far worse horrors that could appear in their place.

When I worked in the archives’ reference room, providing access to materials like this little pamphlet, I always felt that a key value in our archival records was that they allow us to reconnect with the past. Sometimes that past is a more general historical past — and sometimes is part of our own very personal past.

Great resource for anyone working with various types of museum or archival collections including digital.

On Tuesday October 27th myself and a co-worker attended our first ever BC Museums Association conference…and we also had to give a daunting 90 minute presentation! Luckily for us the attendees were a great group of supportive colleagues who seemed really engaged and at the end they asked many questions (and we were able to answer them all)! The presentation was about our Transcribe site which allows the public anywhere in the world to look at our images of old letters and diaries and transcribe them so the handwritten documents become machine readable – in other words searchable through the search function on our Transcribe page. Check out our collections online and maybe you’ll want to transcribe, but I warn you it gets pretty addictive!

![NWp 641.5 B862 [front and back cover]](http://staff.royalbcmuseum.bc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/15_favorite_recipes_cover-500x500.jpg)

![NWp 641.5 B862 [centre fold]](http://staff.royalbcmuseum.bc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/15_favorite_recipes_centre_fold-500x500.jpg)