As we embrace the festive season, I find myself looking at the faces of young children and families as they discover the magic of Christmas. I see the joy and excitement they feel, and wish I could experience Christmas once more through a child’s eyes. Many of us try to capture the excitement in photographs and videos that we share with family and friends through social media.

In years past, these celebrations would have been captured in 16 mm or 8 mm home movies, some of which survive as treasured family artifacts. Some of these films may find their way into archives where they can be safely preserved for the enjoyment of future generations. I hope families will preserve today’s digital memories as they once preserved film footage.

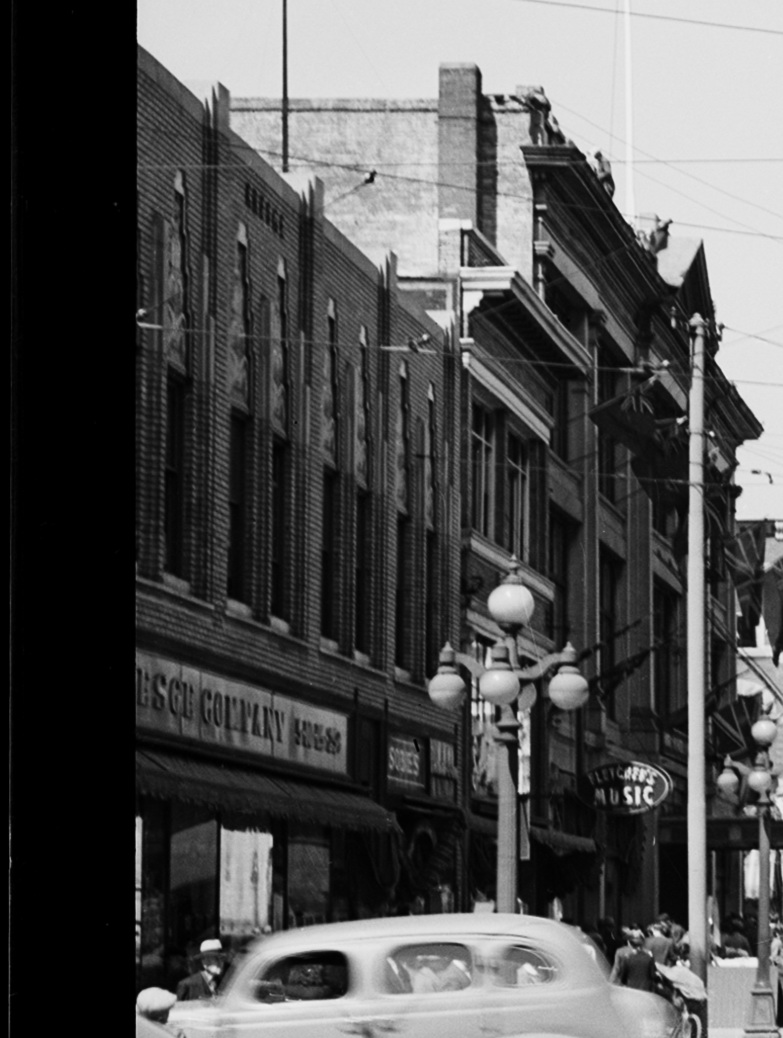

Paul W. Billwiller was a mining engineer who lived and worked in Britannia Beach, BC. We are lucky to have his home movies in the BC Archives collection, especially because they include footage of a series of Christmas celebrations spanning the years 1946-1953. I would think this type of footage is relatively rare—the same annual event being filmed over several years with the same young boy. This video clip of edited excerpts from the home movies begins with young John Billwiller’s first Christmas in 1946. The family is enjoying their celebration and the new baby is propped up in a chair, surrounded by new toys and showered with attention. I suspect that this was the quietest Christmas for this family for a number of years! We see signs of the affluence of the post-war years, but also the relatively modest gifts that the family members receive: the new mother’s sweater held up for display, and (likely) a grandmother’s bottle of eau de toilette. There are shots of the tree, the festive dinner table resplendent with a golden turkey, and the suit jackets and ties worn by the men.

Three years later, it’s Christmas 1949, and we can revisit a toddler’s pleasure and excitement in opening the gaily wrapped gifts. (Oops, what happens here with John’s toy car?) By 1950, John is considerably more excited by the gift opening. He’s a young lad now—did you notice the smaller red table and child-sized chair? I wonder if John plays at this table when it isn’t holding Christmas presents. The train set must have been the earnest wish of many a young child; his has sliding doors on one car. John is fascinated as he watches the train travel along the track. But wait? Is this John’s father playing with the controls? Come on now, Dad, surely John gets a turn!

I think the pinnacle of holiday excitement occurs during Christmas 1953. John looks so excited that he doesn’t know which present to open first. He’s all smiles as he plays with some sort of pellet gun. And look at this—a set of junior carpentry tools, another much-wished-for gift. There are more gifts this year, including the requisite western cowboy’s holster and six-guns, a toy airplane, and a fancy pen. Yet another holiday dinner with the turkey as the guest of honour, escorted proudly to the table by Mother. And remember those festive paper hats—not too close to the candle flame, John!

We’re fortunate to have this material in our collection, preserved with care and attention, ready for future generations to access. It is a window to another time—one that is long past, but still able to evoke memories of our own family celebrations.

Home movies were special; they were different from the digital footage you shoot on your cell phone. The film was a finite resource. A reel of 8 mm film provided fifty feet, or about four minutes running time. The cost of film and processing placed certain restraints on amateur filmmakers, meaning that they would need to carefully plan out what they intended to capture on film. I think it resulted in home movies that were more tightly focused on relevant subjects. You can see that in several of the Billwiller clips—a shot of the tree, long enough to see it but not lingering, shots of gift opening, and of the turkey.

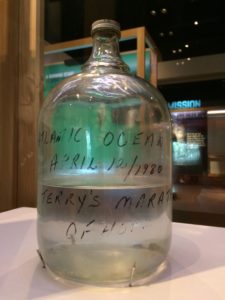

Free of the constraints imposed by the cost of materials and processing, today’s digital movies of family events, often shot on cell phones, seem more rambling and lacking in narrative focus. They don’t tell a story in the same way that a good film does. And, more worryingly, I wonder if today’s digital artifacts are treated differently than physical film. Countless families have stored reels of film for many decades, but how many people keep an old cell phone in a trunk or box in the attic, or migrate its contents to a hard drive? And even if the digital memories are kept, will they always be accessible? A piece of film, even if damaged, can still be held up to the light, and images appear. A digital file needs the right software and hardware to make it accessible. I am not arguing for film versus digital; I just think we should consider how we want to preserve our digital memories. Paul Billwiller’s footage of his son John’s very first Christmas in 1946 is now 71 years old. It tells us a lot about families, and celebrations, and culture. In 2088, will you be able to access your digital memories to remember those long-ago celebrations?