Arbutus menziesii

The Heather Family (Ericaceae) is well known in Canada for its many shrubby species such as blueberries (Vaccinium spp.), salal (Gaultheria shallon) and Labrador tea (Rhododendron groenlandicum; previously Ledum groenlandicum). We in British Columbia are fortunate to have the only tree-sized member of the Heather Family in Canada, the distinctive and handsome arbutus (Arbutus menziesii) also known as Pacific madrone, madrona and strawberry tree.

Arbutus grows into a multi-stemmed shrub or tree with crooked trunks sometimes twisting their way up to 35 m (approximately 120′) tall. The smooth reddish bark stands out from that of all other trees in our province. It flakes off in the late fall, being replaced by young greenish yellow bark from beneath as the trees begin to swell and grow with fall moisture.

Arbutus Bark. Image courtesy of Dr. Richard Hebda.

Leathery, oval evergreen leaves cluster toward the ends of the branches. Above they are shiny green, but below they are pale. Typical leaves range from 5-15 cm (2-6”) long, Young shoots bear finely toothed leaves whereas those of mature shoots have no teeth.

Like bunches of grapes, great clusters of creamy or pinkish white, honey-scented flowers adorn the ends of the branches. Each small flower resembles a tiny white bell, pinched in at the mouth. The tips of the petals form five little teeth, a feature common to many flowers of the Heather Family. Within the flower nestle 10 stamens and a single five-parted pistil.

Brick-red berries form in the late fall and persist well into winter. Each fruit in the cluster is about a centimeter (0.4″) across and covered by tiny little bumps. Birds, especially grouse, feast on these attractive fruits.

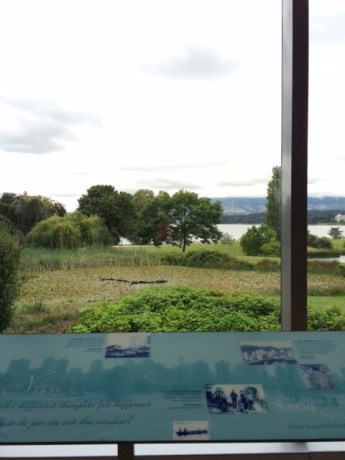

The geographic range of arbutus hugs the Pacific Coast of North America from southern British Columbia to California. In our province, arbutus occurs on the southern two-thirds of Vancouver Island, especially the east side, and the adjacent Mainland almost to Knight Inlet. Rocky knolls and cliffs provide the classic hang-out for the species. The tree appears to wrest nutrients from the bare rock itself. Arbutus grows extremely well in open dry Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) woodland and forest, where the soils are deeper. On these sites, trees can reach great girth and height at times forming “magical” groves. In Victoria arbutus trees and shrubs appear in boulevards and on roadside banks “inoculated” so to speak, by perching birds

Once established, arbutus makes a superb, undemanding garden and landscape plant. Evergreen leaves, exquisitely attractive bark, beautiful flowers and brilliant berries are outstanding features. The only drawbacks may be the cleanup of the leaves, particularly in the late summer, and the lack of frost tolerance. There is also a stem canker present in the region which can kill branches.

Arbutus Berries. Image courtesy of Dr. Richard Hebda.

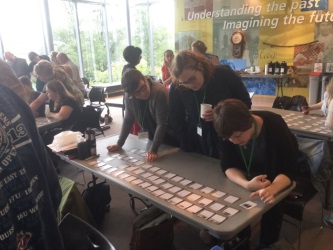

The easiest way to have arbutus on your property is to leave and encourage already established plants. You can raise arbutus with relative ease from seed sown in the fall and covered lightly in a peat-potting soil-sand mixture. If you have a very dry south, or west-facing site, simply spread fruits collected in the fall, and you will be surprised at the rate of successful germination in places where you could never expect to plant a seedling. Arbutus plants larger than 20 cm (8″) tall are almost impossible to transplant and should never be dug up. Move only seedlings from waste sites with loose soils in the wettest part of the winter. Be sure to dig up the entire root and keep as much of the soil attached as possible. Occasionally, potted seedlings are available at garden centres and native plant sales.

Aboriginal peoples put arbutus to assorted uses in technology and medicine. Saanich people used the wood for spoons and gambling sticks. The Sechelt made keels and sterns for small boats from the hard wood. Dye from bark was used to color wooden utensils and camas bulbs in cooking pits. On the Saanich Peninsula, leaves and bark yielded medicines for colds, stomach problems, tuberculosis and birth control.

The dense hard wood is widely used for artistic carving, taking polish very well. It also provides hot slow-burning firewood.

The scientific name Arbutus is the same name as Romans used for a similar and closely-related tree known as the Strawberry tree (Arbutus unedo) The species name, menziesii, honours Archibald Menzies, Royal Navy botanist and surgeon, who collected many plants in our area in the 1780’s and 1790’s.

You can see and learn more about arbutus and many other members of the Heather Family at the Native Plant Garden of The Royal British Columbia Museum, 675 Belleville Street, in Victoria, B.C.

![NWp 641.5 B862 [front and back cover]](http://staff.royalbcmuseum.bc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/15_favorite_recipes_cover-500x500.jpg)

![NWp 641.5 B862 [centre fold]](http://staff.royalbcmuseum.bc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/15_favorite_recipes_centre_fold-500x500.jpg)