Even before I was hired as a museum curator, I was asked to write 28 species entries for some obscure fishes in Animal: the definitive visual guide to the world’s wildlife. I had to take painfully dry science and distil it into 45 or so words that anyone could understand. That set me on a dark path (cue sound effects) to the hidden vaults of museum collections and my laboratory. Who doesn’t want a laboratory full of bones?

The skeleton of an Olive Ridley Sea turtle in my laboratory.

Museum work dwells in obscurity, and a great proportion of BC citizens have no idea that RBCM staff publish academic research on par with university professors. We have an annual research day where museum staff tell other staff-members what is going on here – because we often tend to work in isolation and forget to trumpet our own successes. Short story is: Yes we do research – but to quote a friend’s daughter, “It’s not rocket science.” Some people question the value of museum research since it is not generating food, medicine or some other product essential to the Canadian economy. But not everything has an immediate practical value.

A North Pacific Argentine (Argentina sialis) from BC blasts off into academic obscurity. Modified from: http://www.forwallpaper.com/wallpaper/takeoff-launch-rocket-fire-smoke-baikonur-240897.html

People spend hours debating whether Pluto is a planet or not, and we spend billions of dollars on rockets and probes to examine our distant neighbours. We won’t colonise that planetoid/planet – so why spend so much energy debating its celestial designation? We debate it because people love to learn about new things – and let’s face it, people love a good argument.

Pure science has its own unique value – it is unlike other fields of study. If we look back, there was a time when electricity was considered a mere curiosity with no practical application. That is hilarious from a 2015 vantage point, as I bask in fluorescent light, the hum of the light’s respective ballasts in my ears, with several electronic gadgets at my fingertips. Much of what we do in museum research and collections development appears to have no practical value. We collect and study objects with no idea how they will be used by future generations. Perhaps the Louvar and Finescale Triggerfish are the vanguard to future drastic changes to the Pacific Ocean’s ecology. Perhaps not. I have no idea whether anyone will ever look at those fish again.

We commonly get accused of stamp collecting – merely trying to collect one of everything just to say we have a complete set. Perhaps my collection of Star Wars cards predisposed me to a life as a museum scientist. Now that I think of it, we actually have packs of Star Wars cards in the RBCM’s Human History collection. I wonder if the museums packages still have the horrible tasting chewing gum? But I digress…

Instead of being satisfied with one of everything in Natural History (a philatelic approach), we keep collecting. We collect year to year from different areas, males, females, young, old, eggs, tadpoles, oddities, etc., and in all Natural History disciplines, the one commonality is that we do specimen based research. We don’t have labs full of machines that go ‘ping’, unlike university biology departments – which to me look more like chemistry labs these days. But at a museum, we still have preserved specimens – plants, crabs, fish, fungi, lichen, birds, whales… This is a taxonomists playground. University researchers come to us when they need material for study (DNA, hair samples, or to make measurements from historic specimens) – just today I had a request for feather samples from White-crowned Sparrows. Museums also are as close to a time machine as you can get outside of science fiction. At museums you can hold an animal or plant collected 100 or more years ago. Nowhere else provides this sort of service to science and society.

But who cares? What is the point of discovering a new fish in BC waters? Or unravelling a species complex of beetles or stickleback? For me, the research generates knowledge for the simple pleasure of knowing stuff. I get a research paper published and maintain a publication record as a fish nerd – and that is enough for me. Do you benefit from scientific introspection (AKA navel-gazing)? I say yes.

People did well enough before the Victorian era, even though the present diversity of nature was far from understood. But ships in the 1700s and 1800s carried frenzied explorers to far corners of the world, in a grand age of biological stamp-collection. The race was on to catalogue nature and this continues even today. Without a proper understanding of species boundaries, all other branches of biological science and medical experimentation collapse. There is no sense comparing the effects of a drug on Norway Rats relative to a control group of un-medicated gerbils. It may seem simplistic to say that, but if we don’t understand species, we could be comparing quite different organisms rendering scientific results meaningless.

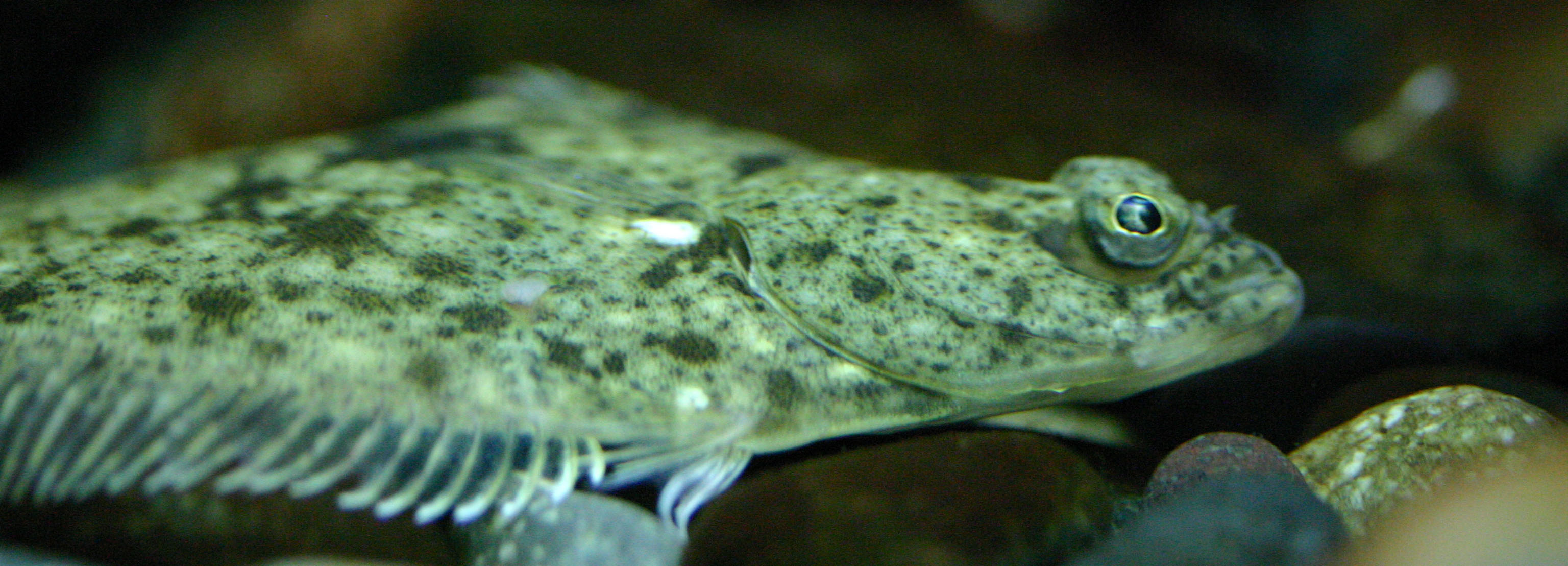

As a practical example of your reliance on science, try figure out what species of fish are in your local grocery store. Sure the labels says “sole”, but which one? Is that a local species? Or imported from Europe? Could one of them represent an endangered species? Are all the fish in the same tray from the same species? You may not be interested in a museum article on the identification of a single fish, or the RBCM’s contribution to DNA barcoding, but you may be ecologically conscious and want to make informed dietary decisions. Without proper identification, or if the basic taxonomy is wrong, we all flounder in ignorance. Even your grocery store choices depend on basic museum science.

Beyond practicalities on an individual level, does the museum as an organisation benefit from obscure research? Again yes. Active study maintains the institution’s reputation as research facility. It shows we are engaged, and that we continue to discover new things. The research helps build the collection – a biological library which generates even more scientific study. We stockpile museum specimens and information for the benefit of society. Museum researchers generate primary literature for academic discussion, but we also filter volumes of information to create concise content for public consumption. We bridge the gap between hard-nosed science and the hard-working public. A museum fails when it isolates collections and researchers from the public. What is the point of a museum collection if no one sees it, no one studies it, and the information is not shared.

There is no point collecting specimens only to lock them away forever.

There is no point collecting specimens only to lock them away forever.

How can you keep current with our scientific advances and collection development? Our work is available globally in scientific journals. However, peer-reviewed science is mostly held in university libraries, and online access to scientific articles can be an expensive cure for insomnia. We also make our work available in a more casual format. You can visit in person and stroll through our galleries, take a collection tour, view one of our travelling exhibits, and we are also just a click away with blog articles, museum magazine articles, and web portal content. There are many ways the RBCM bridges the gap between pure academic research and the interests of every-day museum visitors. You don’t expect to learn about Pluto at the RBCM, but you do come here to learn about British Columbia and connect with our vibrant research community. We are irrelevant without you.