Sometimes the most mundane tasks can lead to the most interesting discoveries.

One of those mundane but essential tasks is the compilation of inventories. My department wants to ensure that all of the colour transparencies and slides of our Paintings, Drawings, and Prints (PDP) collection have been scanned, uploaded and attached to their online descriptions in AtoM. We need an inventory to assist with this. It’s a pretty straightforward process: I look at the transparencies, list them by PDP number, determine if the image is already available in our digital repository, check that a description exists in AtoM, and see if a scan of the image already appears online. I have a good eye for detail, and I find a number of anomalies I’ll need to straighten out.

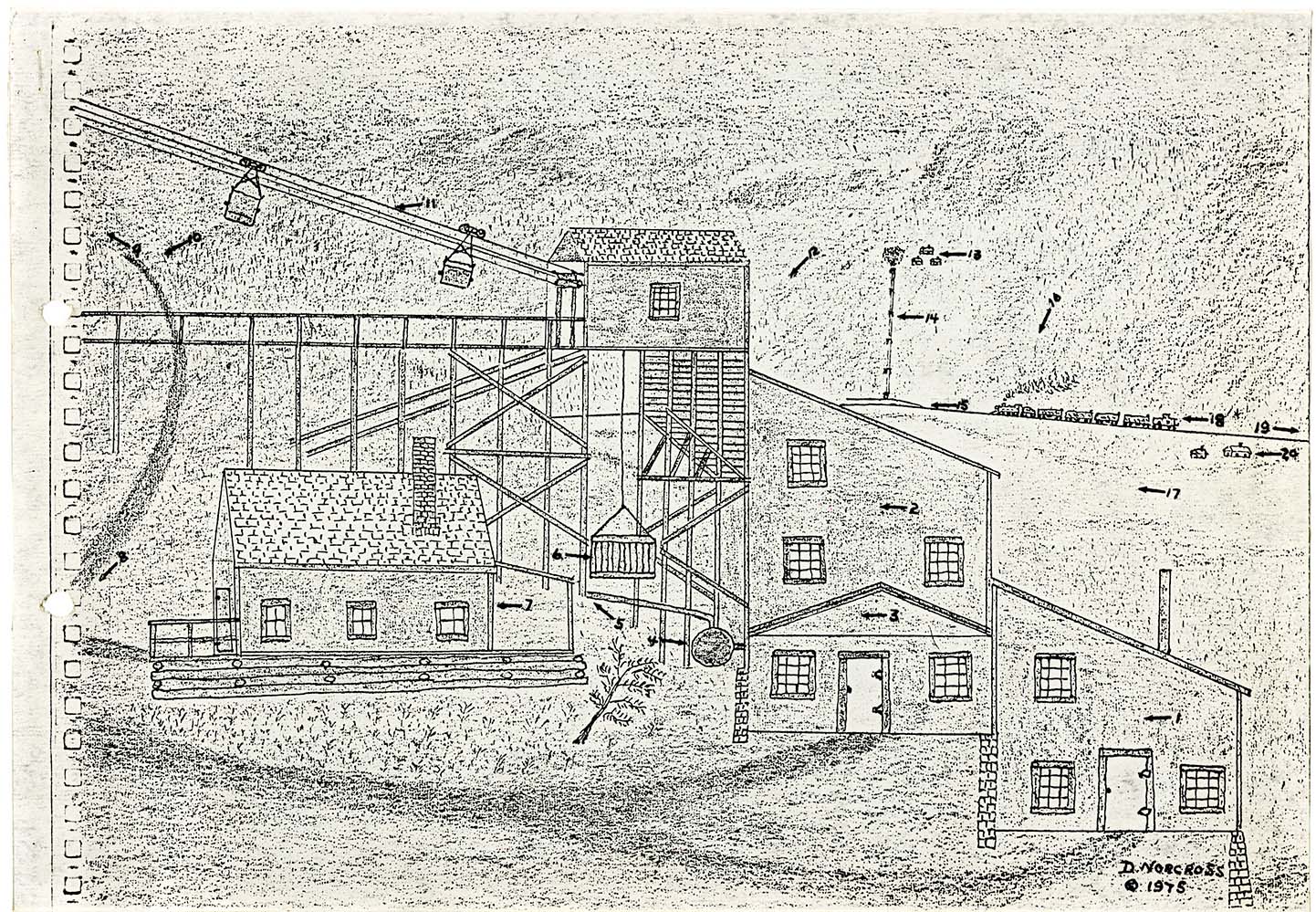

Then I lift a transparency to the light and I see a colourful image that reminds me of the folk art of Maud Lewis. I pick up another, and it is more of the same. These images I am holding in my hands are colourful, and with one or two there is a sense of whimsy. I think it is the sense of motion and the relationship between space and perspective that reminds me of Lewis’s work. Taken as a group, they are very detailed and technical–yet they are not technical drawings.

These transparencies make me eager to see the originals. A colleague and I go into the PDP vault and locate the container. We find that the colours in the originals are far brighter than those in the transparencies; they appear to be drawn in pencil crayon. The subject of all of the drawings is mining in British Columbia. We’re entranced by the originals—the passion the artist has for his subject is clearly evident.

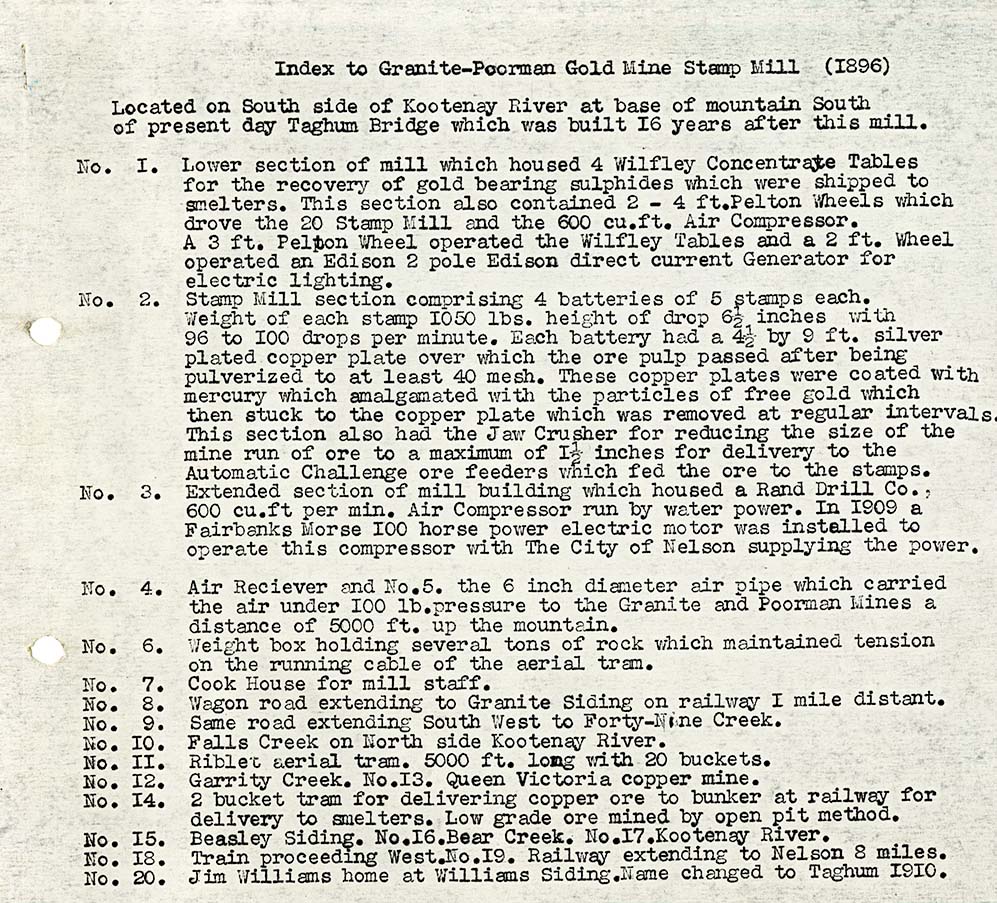

While compiling his memoirs, David Henry Norcross (1901-1980) gathered his drawings of early mining into a collection he named “Recollections 1975.” The container holds more than the colour drawings. Within a brown binder anchored by a metal clip, there is photocopied material meant to act as an index or finding aid to the images. This material includes copies of the drawings and written commentary to accompany each image. This includes description of machinery, transport, mining tools, miners, mine sites, and history. On the copies of the drawings, Norcross has numbered certain points, which then correspond to points in the commentary. Unfortunately, the paper appears to be from an earlier form of photocopying, and the ink used on it has already faded. I’m glad that I’ve discovered this in time, and I make a digital preservation surrogate. Now, at least, we will have a stable preservation copy of the information provided by Norcross.

The man who made these drawings also wrote “I am not an artist” in the introduction to his material. I think that simple statement expresses one rationale for our PDP collection. It is a documentary art collection, where the pieces are acquired and preserved because of the visual record they provide of British Columbia’s past. This isn’t about pieces of fine art; it is about documenting specific times and places, people and activities.

Norcross was born in the Kootenay area; primarily lived and worked in the mines of British Columbia; and, ultimately, died in the Kootenay area searching for one of the mines he so loved. He was born in a Granite Siding homestead and began his mining career at age 16. He travelled throughout BC, working in approximately 50 mines. He was closely associated with the Chamber of Mines of Eastern BC and was widely recognized for his knowledge of mining in BC. His obituary noted that with his death, a vital link to the oral history of mining has been lost. But his knowledge of mining has not been lost; it exists here in the archives in his lovingly depicted scenes of mining. The Norcross collection is a wonderful set of drawings, created by an unknown artist who sought to document what he knew about the early years of mining in British Columbia.