As the museum and archives prepare to move the collections to the new Collections and Research Building in Colwood, BC, more items are arriving in the Conservation labs for treatment to ensure they are stable enough to endure the journey. This past year, one portrait made its way to the paper conservation lab in need of pre-move stabilization. In this case, a large hole and obvious moisture damage were cause for concern.

This portrait of Mr. and Mrs. Lum (BC Archives, J-01350) is one in a collection of four (BC Archives, MS-3411). Mr. Chin Lum Kee, also known as Ah Lum, was born in Guangdong (previously known as Canton), China in 1835. He arrived in the new colony of British Columbia during the Fraser River Gold Rush. While in Sto:lo territory, he met his wife, Squeetlewood, also known as Lucy, who was born in 1854.

The portrait is a solar enlargement, based on a salted paper print (more information on this type of photography below). Black and white crayon have been used to work up the figures’ clothing and watercolour has been used to add soft colouring to the faces and background. In keeping with photographic portraiture of the time, the figures are captured from the chest upward with their bodies fading softly into the bottom of the picture plane. This solar enlargement on paper has been mounted to canvas and stretched over a wooden strainer.

A Brief History of Solar Enlargements

Solar enlargements, also known as crayon portraits, were produced between the 1860s and the early 20th century. During the 19th century, photographic prints were made by placing photo-sensitised paper in direct contact with a photographic negative. Making a photographic print larger than the original negative began to be possible in the late 1850s with the invention of “solar cameras”. These enlarged prints required lengthy exposures and were faint and soft-focused. Furthermore, any imperfections in the photographic negative would be amplified in the enlargement.

As a result, these faint photographs were used as a sort of under-drawing upon which charcoal and coloured paints and crayons were used to retouch and enhance the image. It was common for artists to be employed alongside photographers for this purpose.

The most popular process for these enlarged photographic “under-drawings” was the salted paper print, however albumen prints could be used as well. Bromide enlarging paper was introduced in the 1880s which employed a gelatin emulsion layer available in many different surface textures. For more information on historical photographic processes, visit the Image Permanence Institute’s Graphic Atlas.

Condition Issues

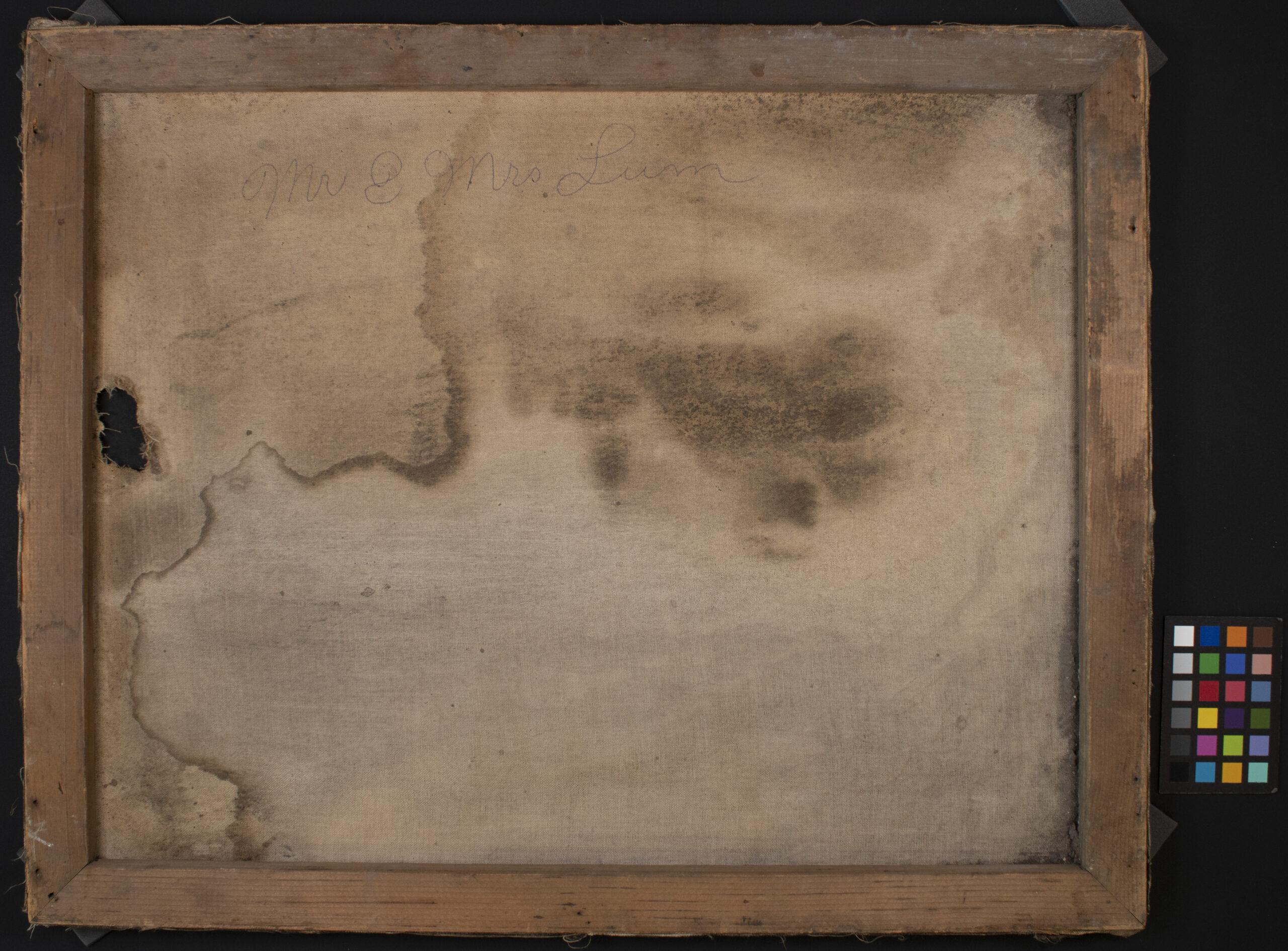

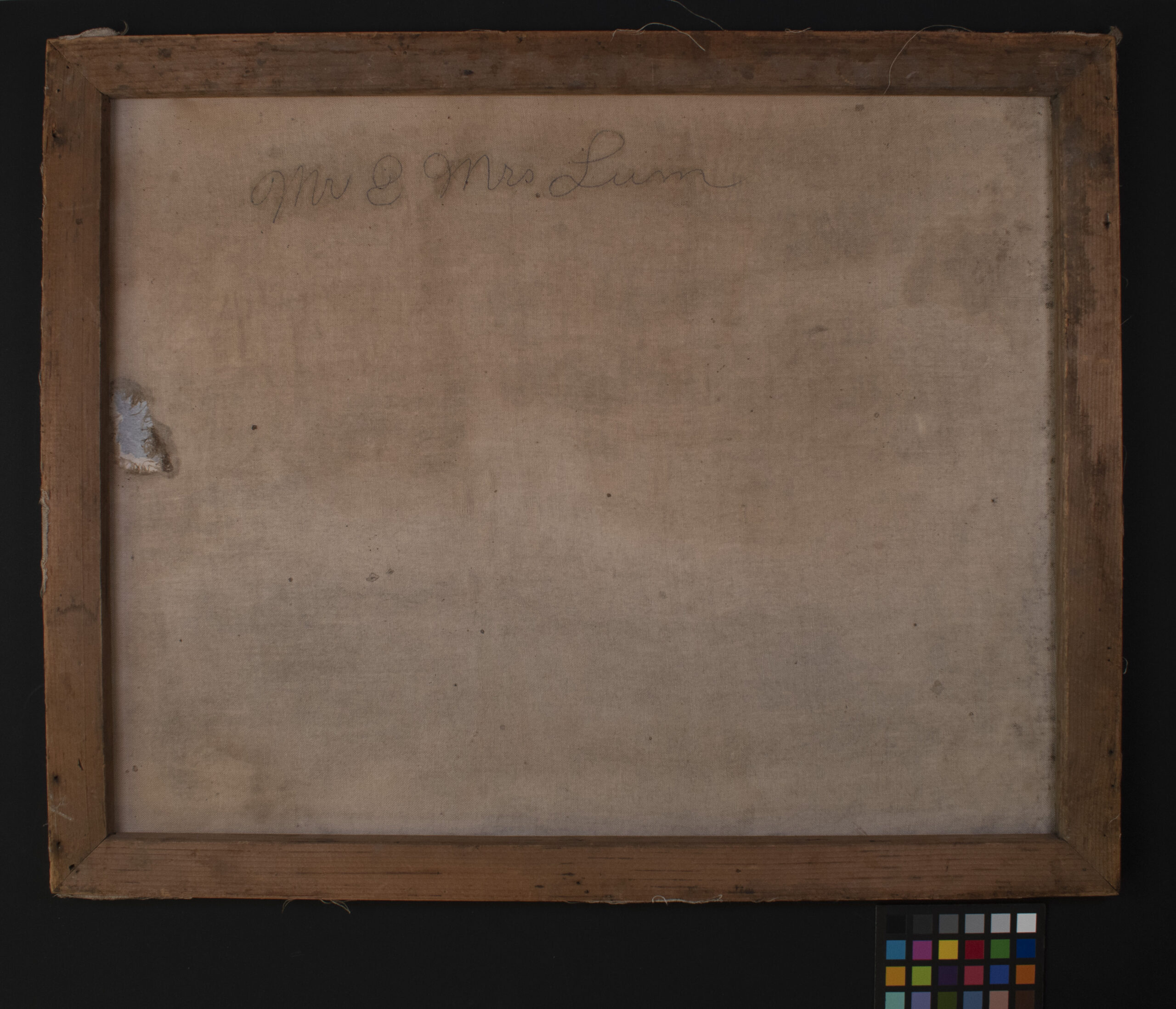

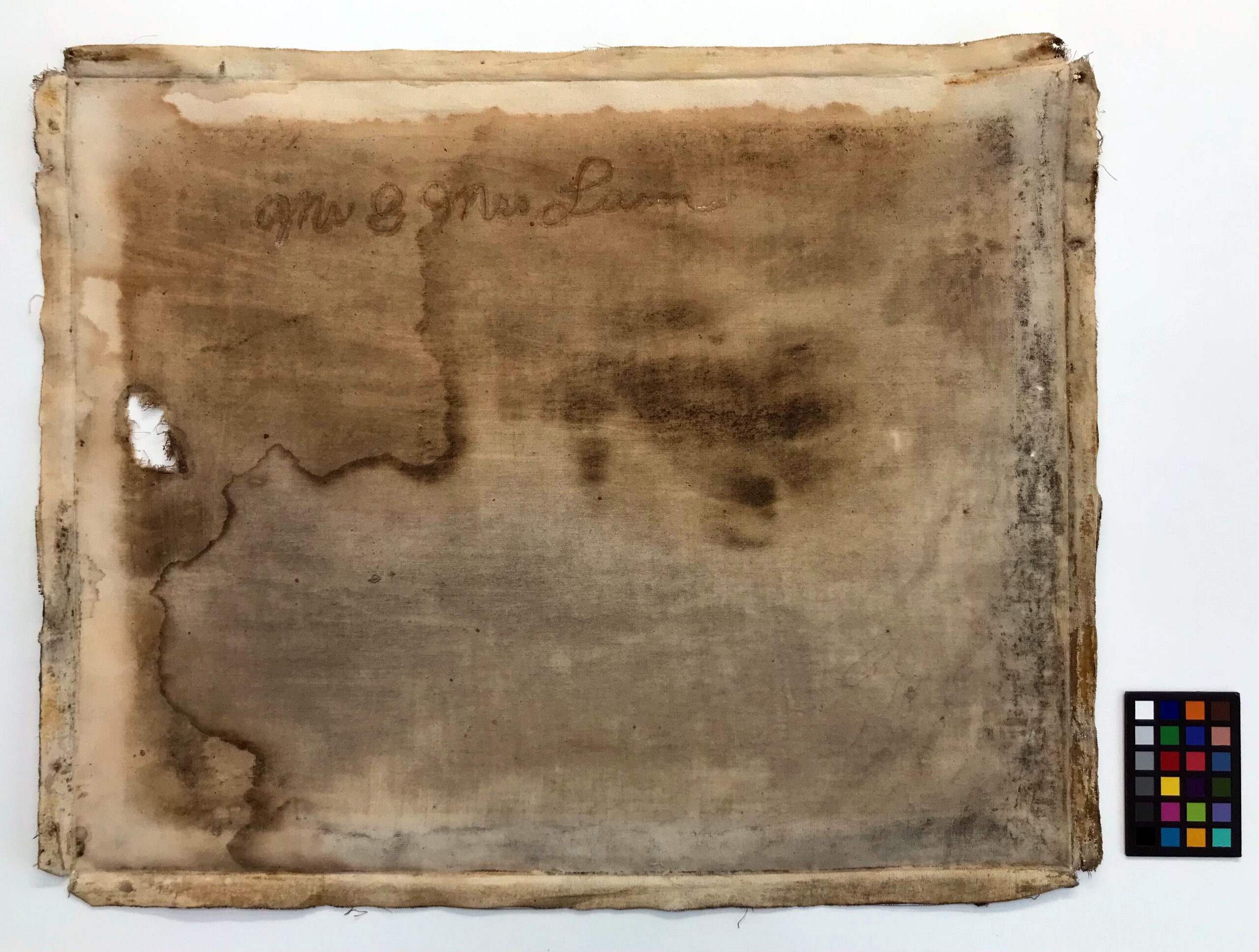

The portrait of Mr. and Mrs. Lum came to the conservation lab because it was not in a condition where it could be safely handled. There was a large hole in both the paper photograph and the canvas behind it. The paper had been worn away along the left edge, resulting in a loss of some of the image. This is likely, at least in part, the result of some previous moisture damage. There were also tideline stains across the image from previous moisture damage. The adhesive holding the paper photograph to the canvas was disintegrating (or previously dissolved?) which meant most of the photograph was not actually attached to the stretched canvas support and was therefore more vulnerable to creases, rips and tears. Finally, the whole structure was heavily soiled with dirt, dust and debris.

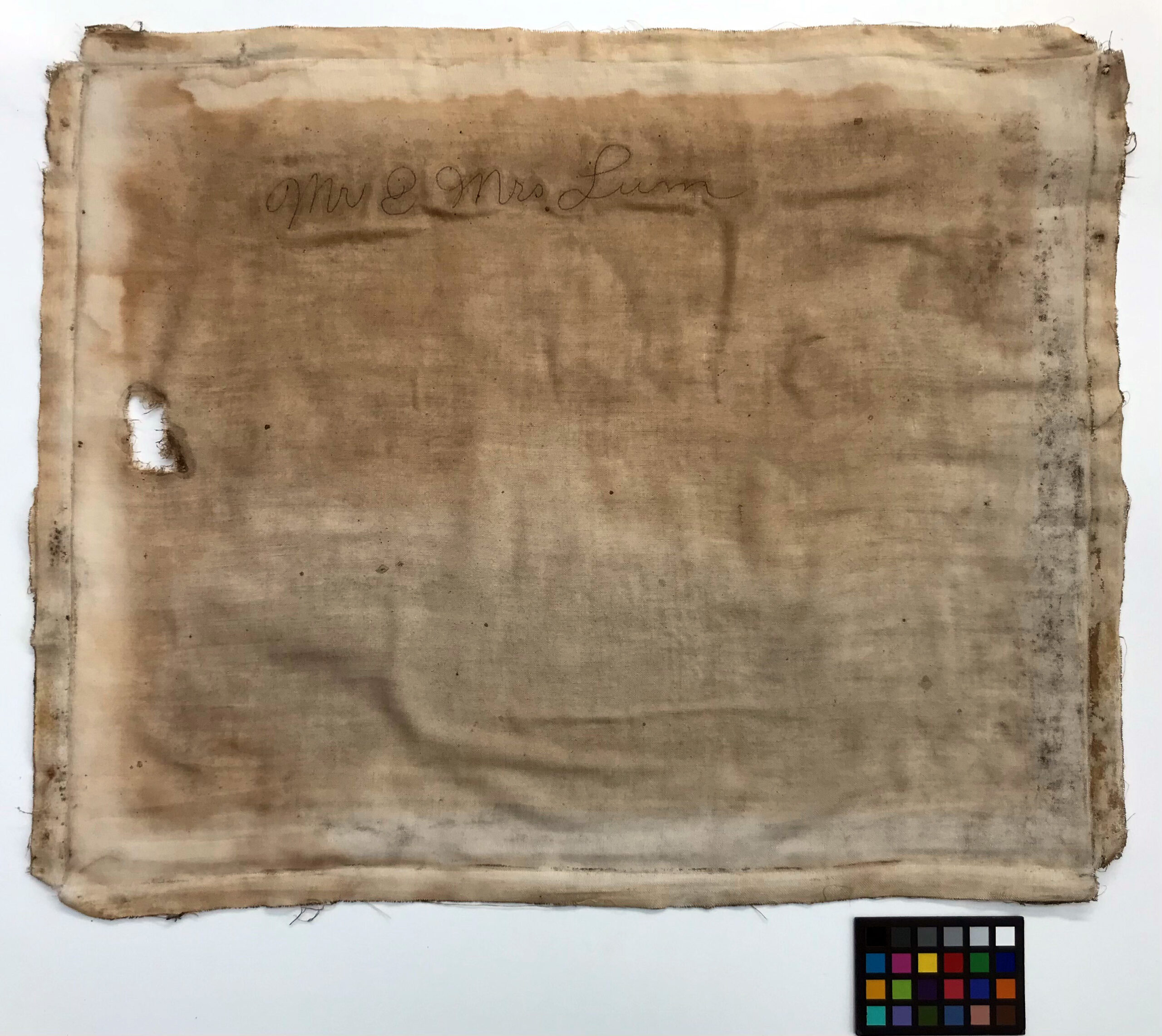

Figure 3. Bottom edge of [Mr. & Mrs. Lum], before treatment. Photograph lifted to show underside of primary support (paper) and the secondary support (canvas).

Treatment

Treating a composite object is always difficult. Since this portrait was so heavily soiled and already stained by moisture damage, an aqueous wash (water bath) was deemed necessary. The decision was made to disassemble the object, which meant removing the partially attached photograph (or “primary support”) from the stretched canvas and then removing the canvas from the strainer. Each piece was then cleaned separately and reassembled once dry.

Cleaning the Primary Support

To be sure none of the media would be affected by washing, solubility testing of all the different media types as well as the staining was carried out under the microscope. The media was already thought to be quite stable—after all, it had survived moisture damage in the past—and the solubility tests proved this to be the case. The tidelines had mixed results with some appearing quite soluble and others less so. These results were enough to suggest that the primary support would benefit from a wash: the media would not be affected and the stains would likely disappear or at the very least, be reduced. Washing out these stains and other products created as a result of deterioration in the paper would also raise the pH, making the paper more chemically stable.

Figure 4. Recto of [Mr. & Mrs. Lum], before treatment. Paper triangles point to areas where solubility testing was carried out under the microscope.

Then, the solar enlargement was washed in an aqueous bath. There were some small fragments that had come detached from the left side of the photograph. These fragments were also washed but using a different, more delicate method. These fragments were gently placed on wet Tekwipe®, a non-woven fabric made from cellulose and polyester. This fabric has capillaries that draw clean water from one basin through the fabric, wetting out the paper resting on its surface and removing dirt and other products of deterioration in the paper and then move the dirty water along the rest of the fabric to the empty basin on the other side.

Figure 6. Primary support being removed from aqueous bath. Note the colour of the wash water has turned yellow with dirt and the water-soluble products that are formed as paper deteriorates.

Figure 7. Small fragments from the left side of the primary support being washed on Tekwipe® using capillary action.

Once washed, all pieces for the primary support were placed under weight to dry flat. After a few days of drying, the photograph was humidified and a thin piece of Japanese tissue paper was applied to the back. This lining provides a consistent support layer and prevents any further losses or tears around the areas that have already suffered losses.

Figure 8. Recto of solar enlargement after aqueous wash and lining with Japanese tissue. Note that some tidelines remain but they are reduced. The staining across Mrs. Lum’s face has been washed away.

Cleaning the Canvas

The canvas was gently removed from the wooden strainer and vacuumed on very low suction to remove loose clumps of dust and dirt that were deposited on the surface, particularly along the perimeter where the strainer had been.

The canvas was also heavily soiled and need a wash, however there is an inscription in blue ink on the back of the canvas that was discovered to be water-soluble during the solubility testing mentioned previously. To protect that ink from being solubilized during the wash, cyclododecane was applied as a temporary seal. Cyclododecane is a waxy substance that becomes liquid when warmed. It was applied over the ink as a warm liquid and solidified in place upon returning to room temperature. One of the unique properties of this wax is that it sublimes (passes directly from a solid state to a gas state) at room temperature over relatively short periods of time.

With the ink inscription temporarily sealed with cyclododecane, the canvas was washed with the help of textiles conservator Colleen Wilson. After the wash, it was allowed to dry and the cyclododecane was allowed to sublime, leaving the ink behind, unaltered.

Figure 9. Paper conservator, Lauren Buttle, applying cyclododecane to canvas to temporarily seal the water-soluble inscription in preparation for an aqueous wash.

Figure 10. Verso of canvas after being removed from strainer, with cyclododecane applied to inscription, before aqueous wash.

Figure 11. Textiles conservator, Colleen Wilson, blotting canvas with a sponge during first bath with detergents.

Figure 12. Verso of canvas 1.5 weeks after aqueous wash and after cyclododecane has fully disappeared.

Cleaning the Strainer

The wooden strainer was also vacuumed to remove surface dirt and dust. Some residual adhesive left on the outside edges of the strainer were re-moistened and removed with a Teflon spatula.

Reassembly

With all the individual pieces cleaned, the lined photograph was reattached to the canvas and then the canvas was re-stretched and adhered to the outside edges of the strainer. The Japanese tissue lining of the primary support provides support over areas of loss.

Re-Housing the Lum Portraits

While the main reason for diverting the Lum portraits to the conservation lab was to stabilize them for the move, there was also the issue of how to safely transport them. When they arrived in the lab, they were altogether in a paper folder, a housing system that was not offering sufficient protection in the context of a collection move.

Once conserved, this portrait, as well as the other three portraits in the collection, were placed in HTS (handling-travel-storage) frames. These storage structures are based on models developed by the Canadian Conservation Institute and the National Gallery of Canada. These frames will provide protection to each work and can be easily re-used for other similarly-sized works if necessary.

References

Canadian Conservation Institute (2018). “Framing a Painting – CCI Note 10/8”. Government of Canada. Framing a Painting – Canadian Conservation Institute (CCI) Notes 10/8 – Canada.ca

Reilly, James M. (1986). Care and Identification of 19th-Century Photographic Prints. Rochester, NY: Eastman Kodak Co.

Whitman, Katharine (2005). “The Technology of Solar Enlargements”, Topics in Photographic Preservation, Vol. 11, pages 104-110. Washington DC: American Institute for Conservation of Historic & Artistic Works. History (culturalheritage.org)