I arrived at the Royal BC Museum in May, just as Mammoths! Giants of the Ice Age was opening. As I walked among the mammoth ivory, I considered the importance of ivory identification. Elephant ivory is regulated due to the threat of poaching. (For more information, check out the United Nations Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, also known as CITES). I recalled flow charts, diagnostic tables, and diagrams, but could I identify ivory in practice?

Although most of our work is stabilization, Conservation has a small store of supplies for restoration, including ivory piano key veneers. I compared these with a souvenir piece of mammoth ivory to see if I could differentiate between elephant and mammoth. The mammoth ivory displayed very clear Schreger lines, crisscrossing patterns visible in cross section, which are only present in proboscidean ivory. I thought I would finally be able to use Schreger lines to distinguish between elephant and mammoth. Elephant Schreger lines cross at an angle greater than 115°. Mammoth Schreger lines cross at an angle less than 90°. More information on how to measure Schreger lines can be found in CITES’ Identification Guide for Ivory and Ivory Substitutes found here.

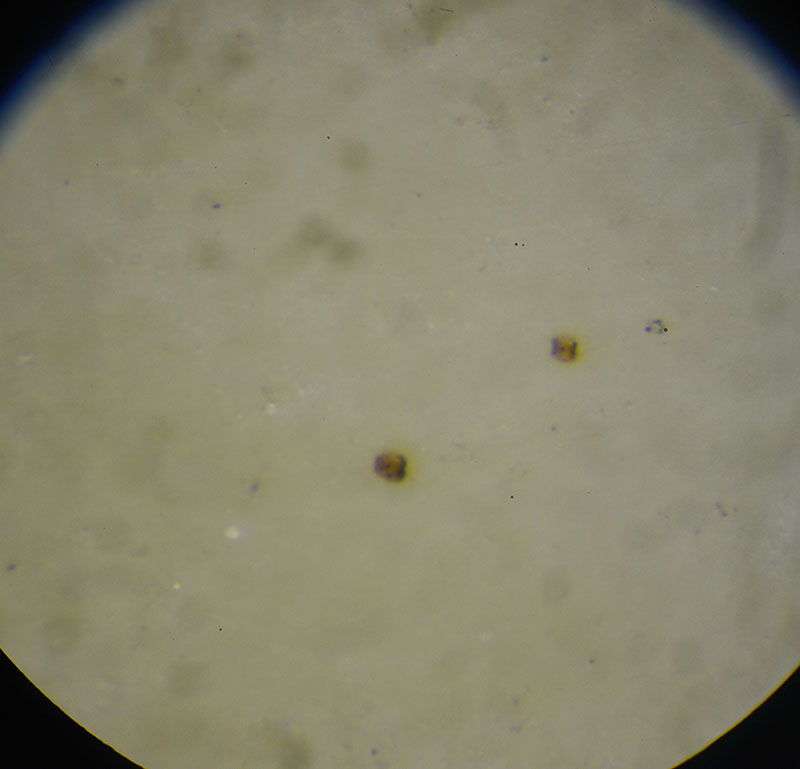

Schreger lines in mammoth ivory

I took five angle measurements from the mammoth ivory and determined a Schreger angle of 92°. This favoured mammoth, as expected, but is technically in a gray zone. Schreger lines are not always conclusive and often not visible on art objects.

There are many ivory substitutes including other animal products and plastics. I found an unidentified piece of “ivory.” It had a different texture and heft and “felt” like plastic to me. I tested my hypothesis using a variety of methods, starting non-destructively.

Ivory has a wide range of fluorescence including bluish white while plastic ivory substitutes fluoresce dull blue. Everything fluoresced bluish, but I couldn’t confidently characterize the colour beyond that. I moved to a static test that I found in Eva Halat’s Contemporary Scrimshaw. I rubbed the ivory samples and unidentified “ivory” with wool and touched them to small polyester fragments. According to Halat, artificial materials retain more static charge than ivory. The unidentified piece picked up and held the fragments … as did the mammoth ivory. Confused, I tried again. Upon closer inspection, I realized the mammoth ivory was coated. The very glossy surface had brush strokes. This may also explain why fluorescence was inconclusive.

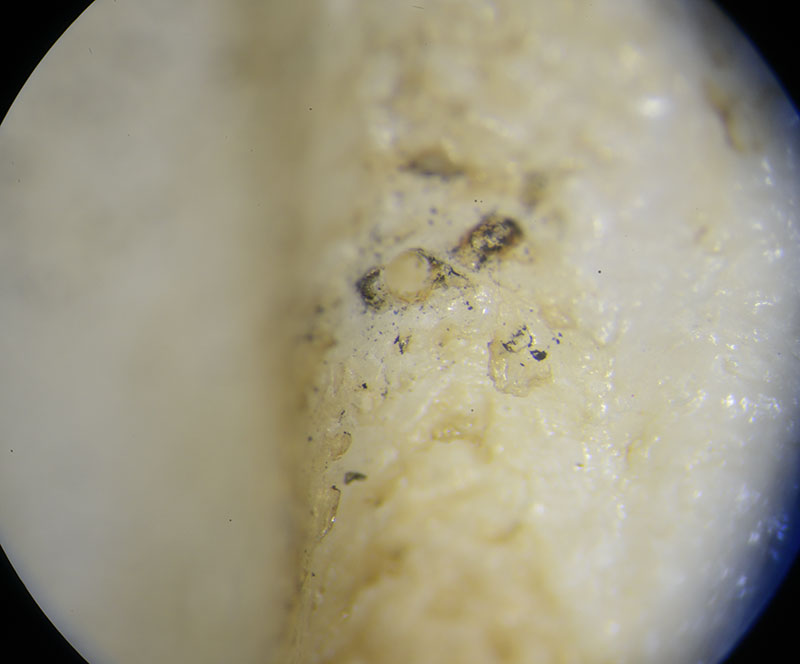

I moved to the destructive “hot pin” test in which a red-hot metal pin is held against the sample; this test is NOT for museum objects! The pin produced small dark burn marks on the veneers. In contrast, the pin sank into the mystery sample, melting the surface. This was dramatic confirmation that the sample was plastic.

This testing could not have been performed on museum collections, but it gave me some hands-on experience for the next time I am presented with “ivory.”

Result of the hot pin test on ivory piano key veneers under magnification. The pin created shallow, charred-looking indentations in the surface.

The result of the hot pin test on the mystery sample under magnification. The pin melted a deep recess in the surface with blackened edges.

Lisa Imamura

Conservation Intern

Queen’s University Master of Art Conservation Program 2016