Not much has changed in the garden itself since late March. Some weeding has been done, and I am specifically targeting a few plants that produce seeds early. Purple Deadnettles are everywhere and the battle with them essentially is a Kobayashi Maru scenario. Hairy Bittercress is another I target early since it catapults its seeds early in spring when the seed pods dry. Other than weeding and a bit of cleanup, we are now starting seeds indoors.

Thyme, tomatoes, basil (the seeds were not faulty), cilantro and peas came up nicely.

The arugula and cress are grown as “microgreens” to go directly into salads and sandwiches instead of into the garden. Growing microgreens is a year round thing for us—we have a small light stand with LEDs to start plants from seeds. We also have some flowering plants just for the flowers.

Leftover potatoes and newly bought onions are getting planted this Eostre weekend.

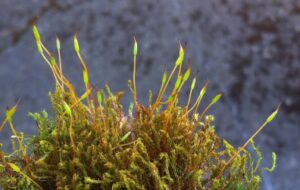

One of my favourite plants in the garden, however, is not something we eat. Mosses—mosses grow like mini forests and while some people power-wash the moss away, I like moss. I wish lawns were entirely made of mosses. Moss is soft on the feet, requires no mowing or maintenance or fertilizer, there is no need for aeration, and it makes plenty of habitat for tardigrades. I may never see a tardigrade in my garden, but I hope they are there and thriving. Since they can survive exposure to outer space, my garden likely is a tardigrade-happy place.

I remember the lifecycle of mosses from my time as a teaching assistant in Intro Biology (course # 71.125) at the University of Manitoba. Moss plants—more specifically, the haploid gameteophyte (gamete producing plant)—we are used to seeing come in a male and female form. The female and male gametophytes produce gametes—egg cells and sperm cells respectively. When water splashes on the male plant, some sperm splashes on top of the female plant, and fertilization of the egg cell occurs. Fertilization of an egg (syngamy) merges each haploid copy of the species genes into one cell (the zygote) which continues to grow with its diploid gene complement.

The sporophyte (or spore producing plant) is the next stage of the plant which grows as a stalk out of the top of the female gametophyte. The stalk elongates and develops a pod (known as a sporangium) at the tip where haploid spores are produced by meiosis. Those haploid spores are released and produce the next generation of haploid male and female gametophytes. This is my memory of the basic moss lifecycle—not bad considering I last taught intro biology labs in the early 1990s.

And I will end this Printemps-post with a gratuitous photo of one of our Common Wall Lizards, one of four (possibly five) which have taken up residence in the front garden. They were basking in the sun at 08:30 this morning.