We rely heavily on technology – integration – connectivity. This was the downfall of the newer generation of Battlestars when the Cylons attacked. Today the government network was down. But it was still possible to connect my phone and a memory stick and write something. And today I am writing about an integrated, connected global network for biological information which at the moment, is inaccessible to me.

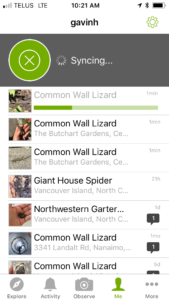

For a few years now I have been collecting lizard range records in a spreadsheet to support a research paper on rapid range expansion in the Common Wall Lizard. That paper now is in-press and will be printed this autumn. Now that we don’t need to be so secretive with our data, we have changed strategies and are encouraging people to report lizard sightings directly to iNaturalist.

iNaturalist is a global initiative where anyone can sign up, and then report the species they find. A global network of experts help make sure identifications are accurate, and the combined efforts of thousands of observers creates incredible maps for each species. Obviously the species reports are biased – the maps detail where humans go, and microscopic life and invertebrates are underrepresented because they are really hard to ID from a simple photo. But fungi, larger insects, plants, vertebrates – all are mapped in amazing detail.

These location records now are available to people around the world to track species ranges and how species ranges may change in the future – climate change, habitat loss – you name it – the data is out there to study.

To enter a record, first you need to get a photograph –you can make a report without a photo – but it is impossible for others to verify what species you found. Photos need to be as good as you can get – a fuzzy blur is not much help. You also can report a sound recording (bird calls for example, or maybe sound files from bat detectors).

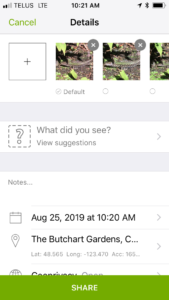

This weekend my wife and I were walking around Butchart Gardens on Vancouver Island, and the organism I found – no surprise – is a Common Wall Lizard. In the case I detail below, I have iNaturalist on my phone, and this series of images depict the process of discovery to creation of iNaturalist record. The process takes seconds.

You take the photos – and this can be tricky – some animals are skittish. I get a basic shot and then slowly close in to get better photos until the subject runs away (botanists and mycologists don’t have this problem). Even a fairly bad photo like the one below is good enough in some obvious cases- but better photos makes identification easier.

Link the photo(s) to the record.

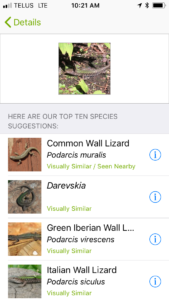

Then you specify what species you think you have found – or you can leave it to genus, family, or blank.

Then you specify the location and date – you can do this manually, or the software draws the location and date from metadata in your photographs.

Then click on the submit record button – and the record now is live for others to view.

If your identification is correct, the global community will also ID the organism as you did, and the record goes to a status known as ‘research grade’.

If you are wrong, people suggest other identifications. You can choose to agree or let the global community of experts come to consensus. Several of my spider and insect identifications have been corrected by experts – and that is the power of this network. We help each other refine the accuracy of these data.

When I take off with my phone to make iNaturalist records, I say I am Nattering. May has well have a fun name for this activity. It is kind of like trophy hunting – but you create a digital record for the world to see rather than a stuffed animal, or pressed plant, or pinned insect. It’s also highly educational – I have no idea of the identity of many of the insects I photograph, but the software and global community really helps teach what is living right in my own neighbourhood.

It costs nothing to load and use the software and for my wife and I, we use it as a fun activity we can share while enjoying hikes on this Pacific island, or while our car charges during road trips.

Why not join the team and photograph what ever you want – starting with Common Wall Lizards and plot their locations in this software. It is fun and you’d be contributing to science.