In museum collections, space is critical. We can’t waste space. Every millimeter of shelving is critical. If you can arrange cabinets more efficiently, do it. Can you pack more jars in a given area? Do it. If you can make space. Do it.

I have been on a binge of deaccessioning lately. What is deaccessioning? It is the museum practice of removing accessioned/cataloged specimens from the collection. Once deaccessioned, we either send specimens to other museums where they are relevant, or give them to teaching collections or perhaps to nature centers. Only rotten specimens are destroyed. We try everything we can to re-purpose specimens before we resort to destruction.

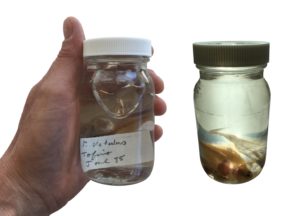

This surfperch, Embitoca lateralis, is a rare candidate for destruction. It has been deaccessioned – someone had cranked the clamp too tight years ago and the glass at the apex of lid popped. Alcohol evaporated and by the time it was noticed, it was too late. If the fish in the jar could speak, they’d say, “There’s a fungus among us.”

Deaccessioning allows me to make space in the collection for new material. Since I am trying to keep the Royal BC Museum’s vertebrate collection focused on British Columbia, the eastern North Pacific Ocean and any adjacent territory, specimens with no relevance to this region obviously have my attention. Specimens with incomplete information (or no information), also flare my obsessive nature and are on my deaccession hit list. Space is created on a jar-by-jar basis.

Putting ‘incomplete information’ in everyday terms – if we are going to meet somewhere, you generally expect some level of detail. If I say I want to meet in Tofino in June, what would you say? Imagine now that I didn’t even give you my name – but still wanted to meet in Tofino in June. I am betting you’d put on your best Monty Python-esque King Arthur and say, “You’re a Loony.” Incomplete or missing data is a real issue.

My long suffering volunteer Jody found a jar of flatfish this weekend which had never been cataloged, but was in the collection. It was only a 125 ml jar – so not a huge waste of space. On closer inspection the fishes were identified (Parophrys vetulus, English Sole), there was a location (Tofino), and a date (June 1985).

Where was I in June 1985 – oh yea – just about to graduate from grade 12. Oh the 80s – I am listening to Duran Duran while typing this – RIO – the obvious choice with its maritime theme.

Yep, that was me in 1985.

Parophrys vetulus is a common fish here in BC, so it is likely you can catch them all around Tofino in June – but it would be nice to know which beach relinquished its sole. And when did it happen? Was it at night? Was it a full moon? On the 1st of the month, or mid month? Were they in ankle-deep water or at 10 meters depth? Open beach or a tidepool? Caught by hand or with a net? Inquiring minds may want to know. And with no collector noted in the hand-written label – I can’t even badger someone by email to jog their memory or review old field notes.

These are the lost soles Jody found. Is one of them yours?

To a museum, data is everything. If you collect and preserve a specimen, record as much as you can about the event. If you are giving me your sole, then tell me its secrets.