On Family Day (February 9th, 2015) I received two hatchling Red-eared Sliders. These turtles are just like any other hatchling red-ears except for one thing. They hatched in British Columbia, and came from the first nest known to have survived our cooler coastal climate. These turtles are native to the south-eastern United States, and range south into Central and South America, and have been spread far and wide because of the food and pet trade, including Washington. They are scattered all over south-western BC and the Okanagan.

An adult Red-eared Slider from Beacon Hill Park, Victoria (my photo)

An adult Red-eared Slider from Beacon Hill Park, Victoria (my photo)

Several nests have been known to survive to near hatching, but our winters prevented survival of hatchlings – yes even the mild winters of south-western British Columbia are too cool – or so we hoped – for Red-eared Slider reproduction. Back in January 2014, researchers with the Coastal Painted Turtle Project discovered nests of the non-native red-eared slider and suggested that this species should be able to breed here in BC. Their excavations of known red-ear nests showed that red-ears are fully developed, but they are hibernating and could emerge in spring if they have enough energy stores for a prolonged hibernation period.

This composite image from a failed nest is from the Coastal Painted Turtle Project crew’s facebook page (photos by Deanna MacTavish).

This composite image from a failed nest is from the Coastal Painted Turtle Project crew’s facebook page (photos by Deanna MacTavish).

One year later – a different nest – and six live hatchlings were found near Painted Turtle nests that were being regularly monitored by staff at Riefel Island Bird Sanctuary, Delta. This is the first record of fully hatched, viable red-eared Sliders in British Columbia. Until now, populations were maintained by a continual stream of abandoned pets. This nest had been opened by Sandhill Cranes. The cranes eat eggs, but left these hatchlings.

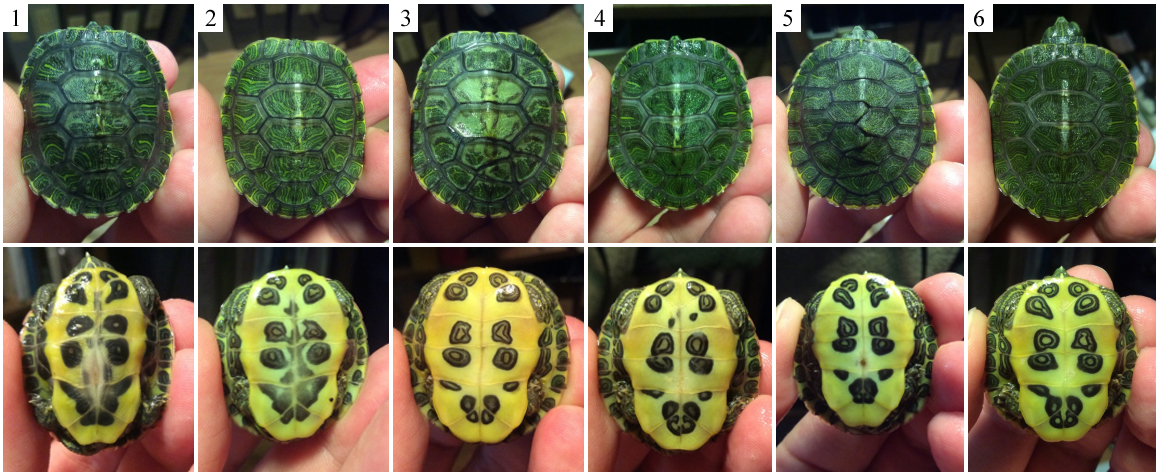

Here are all six hatchlings showing their unique shell patterns – 1 still shows the remnants of its belly button (photos by Aimee Mitchell).

Here are all six hatchlings showing their unique shell patterns – 1 still shows the remnants of its belly button (photos by Aimee Mitchell).

I am keeping only two to show to the public, namely, 4 and 6 – they will be named accordingly – just like Humanoid Cylons. I’ll post updates to their progress over the years. Three and Five showed strange vertebral scutes and this sort of malformed shell is not uncommon in the pet trade animals. I asked for 4 and 6 because they were decent looking well-proportioned animals. I’ll be curious to see if they are the same sex – sex is determined by nest temperature. Eggs incubated at low temperatures (22-27°C) produce males, warmer nests produce females – to a point – over heat a nest and it produces no turtles. One, Two, Three, and Five will be humanely euthanized and added to the Royal BC Museum research collection.

Red-eared Turtles from a failed nest, found when land owners were building a boathouse on Beaver Lake, Vancouver Island (RBCM 1994) (my photo).

Red-eared Turtles from a failed nest, found when land owners were building a boathouse on Beaver Lake, Vancouver Island (RBCM 1994) (my photo).

Nest temperature may be our only saving grace now that these turtles are reproducing here. If British Columbia nests produce all male hatchlings, then eventually the population will fail as sex ratios become too biased. I see very few males in wild populations. I have always assumed this is due to the large size of females, and that people prefer turtles that stay small. Large turtles are far more work (water changes, filter maintenance), and so they get abandoned in ponds, streams and lakes far more often than smaller turtles. But if males are produced by cooler nests, then we may have a population boom until all the abandoned females die of old age (or are removed).

In the meantime, we have to feel sorry for all the Western Painted Turtles in British Columbia – they are our only native freshwater turtle, and will have to coexist and compete with Red-eared Sliders for aquatic habitat and nest sites. With all the development in south-western BC, the last thing a Painted Turtle needs is more competition for their place in the sun.

Red-eared Turtles on log in Matheson Lake, Vancouver Island – not a Painted Turtle among them (my photo).

Red-eared Turtles on log in Matheson Lake, Vancouver Island – not a Painted Turtle among them (my photo).