At its very simplest, a biological specimen in a museum collection is one representative of a species from a specific time and place. Some may say, “Who cares, you’ve seen one Leopard Frog, you’ve seen ’em all”.

Did you see a male? Female? Young? Old? Abnormal? What did it eat? Was it gravid? What diseases or parasites were present? Was it from within its normal range or was it in a new location? Every specimen is different. Every specimen is worth keeping – not just for present-day research – but because each specimen represents a time capsule of biological information. We always save specimens in museum collections precisely because biological specimens are unique. In some cases, species represented in museum collections have vanished from BC. There are very few breeding Leopard Frogs in BC – perhaps like the Sage Grouse, British Columbia’s Leopard Frogs will become extirpated. That’s beyond sad.

But in this era – the Econocene – where we seem to frame decisions on the almighty dollar – what is the value of a specimen? Can you put a dollar value on a dead animal? To break it down to the basics, you have to consider what it would cost to go out and collect a new animal for research. You may also reflect on whether you should kill another animal given present rates of habitat destruction and population declines.

Consider just vehicle rental, fuel, ferry to the mainland (since this institution is on an island), permits, field gear, food for the field crew, and salaries – and if you work it out – each museum specimen at the time of collection is worth hundreds to thousands of dollars depending on where you sampled. You’d think entomology may be the exception because they can dilute the cost per specimen by taking thousands of specimens per field trip – but this is not the case. To paraphrase Claudia Copley:

The true cost to send 3 people into the field and do the work is like that of any other collecting trip (we just happen to be 2/3 volunteers). Although thousands of specimens may be brought back, the real cost emerges during identification. A researcher may charge an hourly rate for identifications, and it sometimes takes a few hours to identify a specimen. In the end, a specimen identified to species in an entomology collection probably ends up having a similar value as a vertebrate specimen.

Entomologists collect thousands of specimens because many cannot be identified in the field, and a large sample is needed to encompass the diversity that is present.

Furthermore, costs always rise (although the price of oil has experienced a hiccup lately). As Lando Calrissian said, “This deal is getting worse all the time”.

Imagine the escalation of costs if you needed to build a time machine – yea – obviously I am doing my usual trick of “one step too far” with this argument. But this is to demonstrate that you can’t slap a price tag on historical specimens like you can with a recently manufactured wrench, or a pair of socks at a department store. There is no amount of money that can send you back in time to sample Leopard Frogs from the 1800s. If we don’t save biological specimens – and properly care for them in museum collections – historical biology will go extinct.

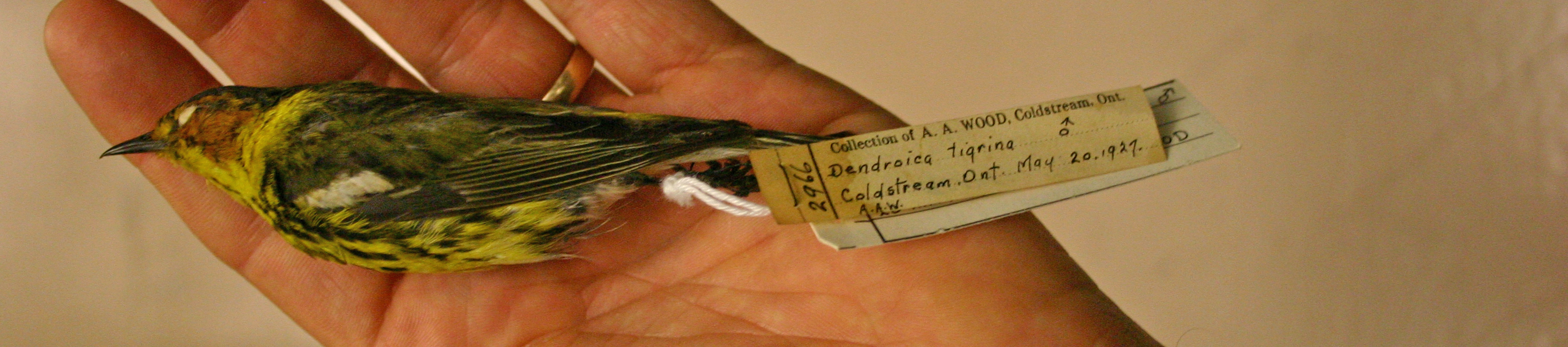

Where else but at a museum can you study a Cape May Warbler from 1927.

Where else but at a museum can you study a Cape May Warbler from 1927.

This thought hit-home yesterday (January 15th, 2015) when a researcher from the University of Victoria was here looking at mammals in our collection. She wanted to see what was available in the collection just in case she had the chance to expand her work beyond Alberta’s borders. Fortunately, we have loads of Fishers in the collection (the mustelid, not people with fishing rods – although we do have historic fishing rods). If the museum had not saved specimens (skins and skeletons, and in some cases, tissue samples), she’d have to request tens-of-thousands of dollars more in future research grants, and spend many long hours in the field (actually this part sounds nice), to get enough samples from BC for her work.

Another researcher came to us for tissue samples of Wolverines – and especially samples from Vancouver Island. Without museum specimens, his work would not be possible. Wolverines are extirpated from Vancouver Island.

Another researcher came to us for tissue samples of Wolverines – and especially samples from Vancouver Island. Without museum specimens, his work would not be possible. Wolverines are extirpated from Vancouver Island.

These are two examples where the foresight of museum experts from over 100 years ago, have ensured that research today is cost effective (and possible). Yes museums spend money maintaining their collections, but can you really put a dollar value on knowledge and scientific advancement? Can you put a dollar value on the snoot-value (prestige) of being the one place in the world where you can study Dawson’s Caribou? How about the value of a bee? Its value as a museum specimen notwithstanding, as a pollinator, bees more precious than gold. You don’t want a world without bees.

Regardless of your interests, you have to agree that museums are unique and worthy of support – financial support. It doesn’t matter whether you want to study Eocene leaves, a Mosquito (the airplane or the insect), or the diet of Cutthroat Trout from the 1930s, collection and maintenance of specimens is costly. Only at a museum can you touch these objects from the past – and in this respect, museums are the cheapest time machine money can buy.

Regardless of your interests, you have to agree that museums are unique and worthy of support – financial support. It doesn’t matter whether you want to study Eocene leaves, a Mosquito (the airplane or the insect), or the diet of Cutthroat Trout from the 1930s, collection and maintenance of specimens is costly. Only at a museum can you touch these objects from the past – and in this respect, museums are the cheapest time machine money can buy.