One of the principles of good conservation is that the work should be reversible. Although there are times when a fabric is so shattered that an adhesive patch is considered, that is a treatment of last resort. Glues tend to change over time becoming discoloured, rigid, and very difficult to remove.

soft sculpture, tapestry (#’s 6 and 28), beading, curved needles (for surgery and carpet) and almost 1,000 #12 sharps

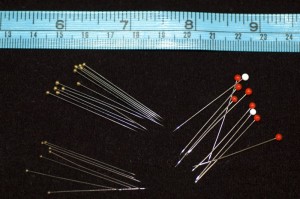

So the work of a textile conservator frequently involves sewing. If a heavy weaving is to be displayed, it needs both an overall support so that it won’t sag under its own weight, and some means of holding it up so it won’t droop and distort. To prevent the yarns of the weaving (or hooked rug or blanket) being split, a large blunt needle is used to stitch between the threads. A hole or damaged area in fragile, brittle silk can be reinforced with a patch placed behind, but only the finest, sharpest needle can pull the thread without causing more damage. Replacing missing stitches in a three dimensional object can mean working in the awkward corners of a structure (like a hat or tent); using a curved needle is sometimes the only way to place the stitches through the original holes.

Pins are a temporary hold. They can keep two fabrics in place until stitching is complete, and they can hold wet fabric in place while it is drying. In both cases, they must be fine enough not to make permanent holes in the fabric. For blocking a washed textile, pins with large smooth heads are easier on the fingers – a lace shawl or crocheted bedspread require a lot of pinning to ensure they dry square.

If you are married to Conservation finding the right tools for the job can be troublesome indeed.