When I was a child, my Dad had a 38 liter aquarium which was stocked with the usual tropical fishes (angelfish, mollies, swordtails, neon tetras, cardinal tetras).

I always loved fish shopping, and at one shop, the front counter was a fish tank and it contained a massive Snakehead. It used to sneak up and stare at you through the glass – and as all good childhood memories evolve, the proportions of that fish expanded over the years. Or did they – some snakeheads grow over a meter in length. Everything seemed larger when I was a kid – especially Wagon Wheels. Wagon Wheels actually were larger in the past – Wikipedia confirms that I am not imagining things.

I always loved fish shopping, and at one shop, the front counter was a fish tank and it contained a massive Snakehead. It used to sneak up and stare at you through the glass – and as all good childhood memories evolve, the proportions of that fish expanded over the years. Or did they – some snakeheads grow over a meter in length. Everything seemed larger when I was a kid – especially Wagon Wheels. Wagon Wheels actually were larger in the past – Wikipedia confirms that I am not imagining things.

![800px-Snakehead_-_Channa_argus[1]](http://staff.royalbcmuseum.bc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/800px-Snakehead_-_Channa_argus1.jpg) Image source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Snakehead_-_Channa_argus.jpg

Image source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Snakehead_-_Channa_argus.jpg

We are lucky that snakeheads (Channidae) are not popular in the pet trade, because the pet trade represents a significant source of exotic species in North America (see: Padilla & Williams 2004, Strecker et al. 2011). Snakeheads are terrible fish in home aquaria – unless you like cannibalistic macro-predators that will kill or maim any tank-mates they cannot swallow. Their nasty habits are one of the reasons snakeheads get dumped into waterways of North America (see Fuller et al. 1999 for a state-by-state summary of snakehead samples). Snakeheads outgrow home aquaria, and owners outlive their interest in these macro-predators. Other snakeheads get released in efforts to establish private culture ponds for food, or for angling opportunities. All three reasons for release reflect selfishness, and a complete lack of respect for natural ecosystems.

Again going slightly off topic: I always liked putting snakeheads and milkfish side-by-side on ichthyology lab exams – spelling counds (oops, counts). The family names for each are Channidae and Chanidae respectively. For the same reason it was fun to have a lab exam question where students had to identify families for marine angelfish, damselfish, snooks, and bluefish (Pomacanthidae, Pomacentridae, Centropomidae, Pomatomidae).

Snakeheads are predatory fish, and the family contains two genera: Channa ranging naturally from northeastern Russia south to Java, and west through India to Afghanistan and southern Iran, and Parachanna from west Africa. The Northern Snakehead (Channa argus) reaches 1.8 meters in length, but others only reach 17 centimeters (a better bet for your home aquarium). Snakeheads are well-known for their air breathing habit, allowing them to survive in hypoxic water and during overland excursions. Some exchange oxygen and carbon dioxide through their skin when buried in mud (to survive drought). Strangely though, snakeheads in warmer water may drown if not permitted access to air. Others (Channa argus) survive in ice-covered ponds.

![wchanna-argus[1]](http://staff.royalbcmuseum.bc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/wchanna-argus1.jpg) Image source: http://www.invadingspecies.com/wp-content/gallery/Northern-Snakehead/wchanna-argus.jpg

Image source: http://www.invadingspecies.com/wp-content/gallery/Northern-Snakehead/wchanna-argus.jpg

Courtenay & Williams (2004) provide details on many snakehead species, including all known introductions into the United States. They, and Courtenay et al. (2004) included key anatomical features which we used to correctly identify the snakehead caught in Burnaby (Scott et al. 2013). Most North American snakeheads are found one at a time, as was the case here in British Columbia and in Ontario, but if small groups are released, they may establish breeding populations. Bullseye Snakehead (C. marulius) in Florida were thought to have originated as an intentional attempt to develop a sport fishery (as if the other 121 exotic species weren’t enough – actually this number must be higher now). Blotched Snakeheads (C. maculata) are established in Hawaii from an introduction dating back to the late 1800s (Yamamoto & Tagawa 2000). The snakeheads introduced in the late 1800s presumably were for food. Today, Chevron Snakehead (Channa striata) also are cultured in Hawaii as a food fish, but so far they remain captive. A breeding population of Northern Snakeheads also had established itself in a single pond in Maryland, and in 2002, about 1200 fish were removed after treatment with Rotenone.

A large Flowerhorn Cichlid (a man-made hybrid that doesn’t exist in nature) from Benvoulin Ditch, behind the ECCO Centre at Mission Creek Park, Kelowna, May 2011 – the cellphone makes a great scale bar.

A large Flowerhorn Cichlid (a man-made hybrid that doesn’t exist in nature) from Benvoulin Ditch, behind the ECCO Centre at Mission Creek Park, Kelowna, May 2011 – the cellphone makes a great scale bar.

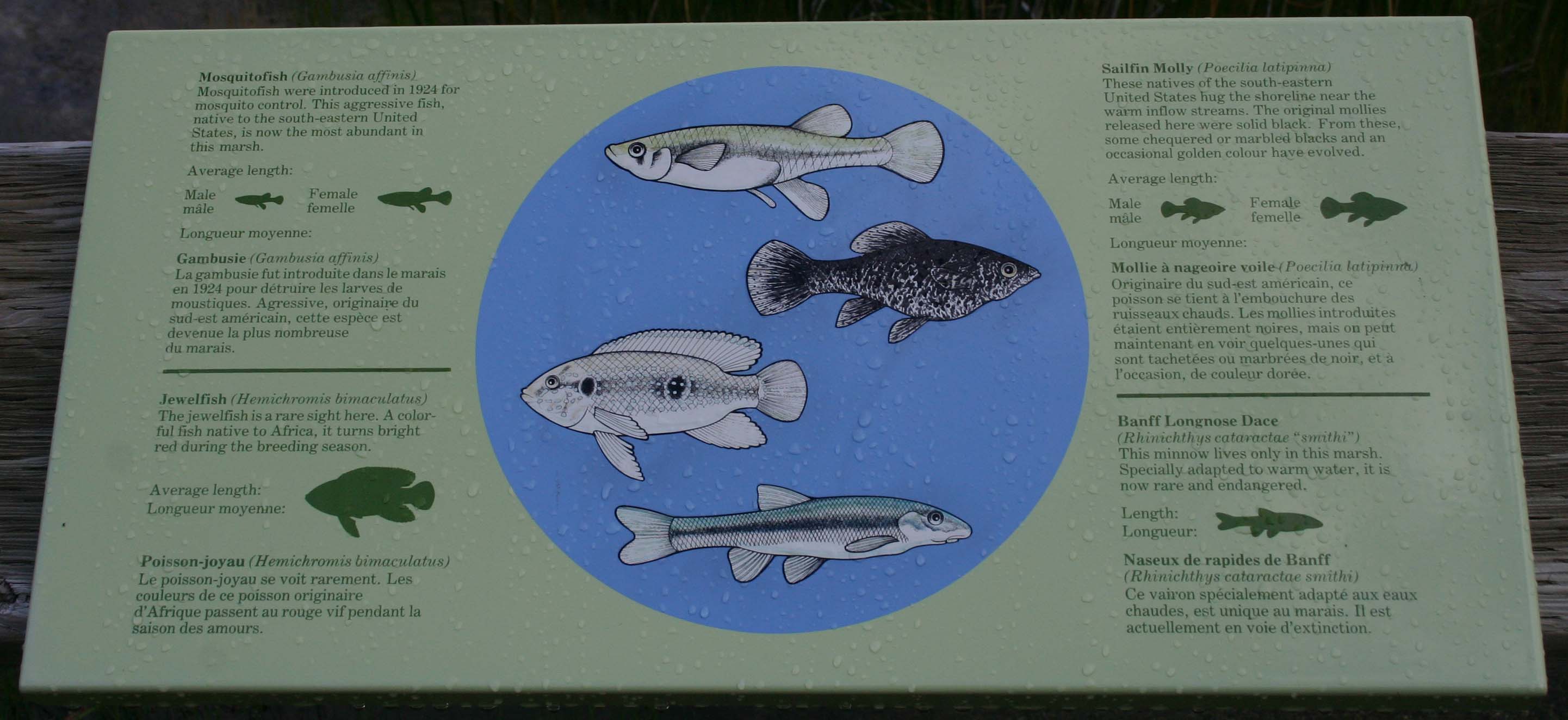

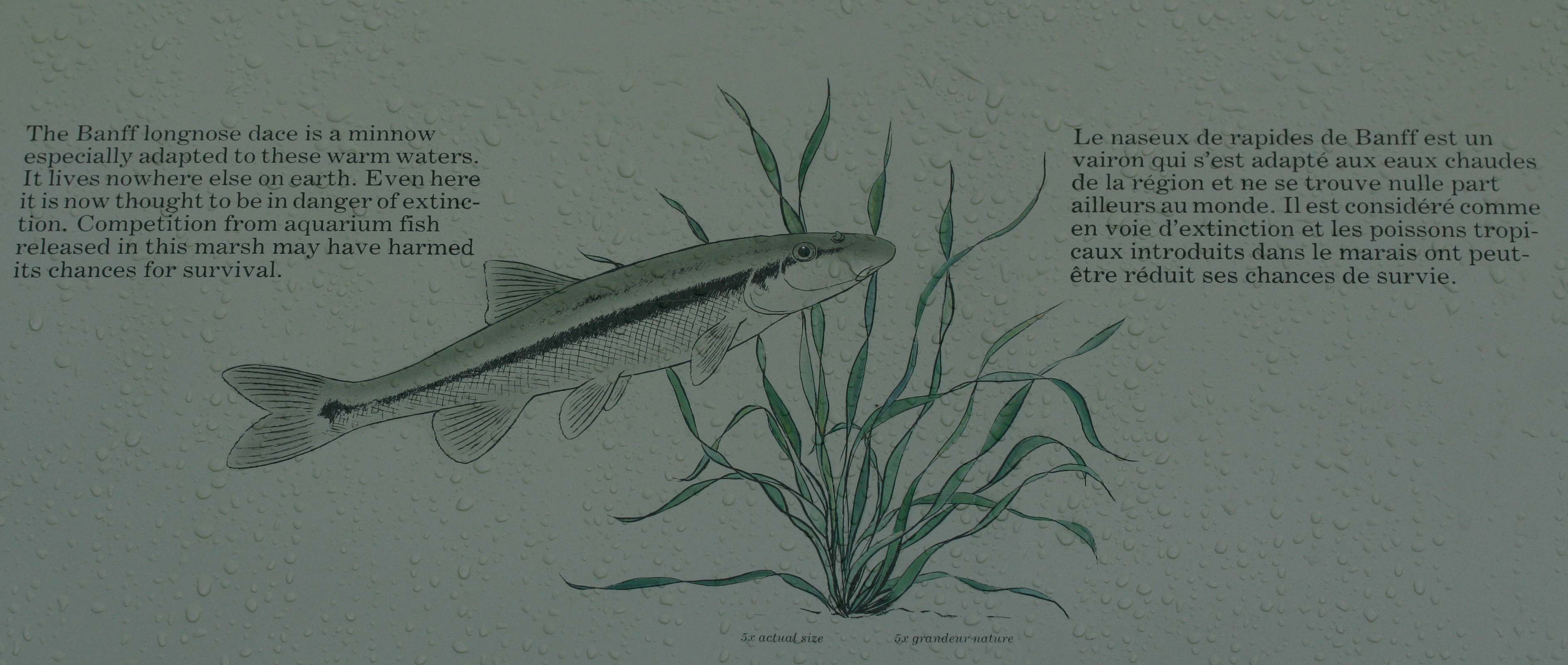

While tropical fishes commonly are dumped into Canadian waterways by careless pet owners, snakeheads are rarely found – probably a reflection of their frequency in pet shops. We have records of Pacu, Oscar, Blue-eyed Plecostomus, and Flowerhorn Cichlids in BC, and Jewel Cichlids, Convict Cichlids, Angelfish and a few other species in Alberta. Jewel Cichlids in Alberta survived to reproduce alongside Mosquitofish and Sailfin Mollies in the Banff Hotsprings. It is embarrassing that these abandoned pets now are tourist attractions in a National Park and the interpretive panels gloss-over the fact that the native Banff Hotsprings subspecies of Longnose Dace (Rhinichthys cataractae smithi) is extinct.

There also are anecdotal records of Pike Cichlids dumped into Lake Manitoba, Piranha into Langford Lake (on Vancouver Island), and photos of a Pacu in Netley Creek in Manitoba (2008), and I suspect what we know is just a fraction of what is released. At least Canada’s climate will kill most aquarium fishes, and colorful tropical fishes are obvious targets for predators.

There also are anecdotal records of Pike Cichlids dumped into Lake Manitoba, Piranha into Langford Lake (on Vancouver Island), and photos of a Pacu in Netley Creek in Manitoba (2008), and I suspect what we know is just a fraction of what is released. At least Canada’s climate will kill most aquarium fishes, and colorful tropical fishes are obvious targets for predators.

Scott et al. (2013) detailed the capture of the Blotched Snakehead (Channa maculata) from a shallow man-made pond in Central Park in Burnaby, British Columbia. The Burnaby Blotched Snakehead was examined at Simon Fraser University’s Biology Department, and transferred to the RBCM on October 22, 2012 (temporary receipt R8165), but is not yet cataloged in the RBCM collection. Originally officials feared this fish was a Northern Snakehead, but genetic analysis and its anatomy showed it to be a Blotched Snakehead – a tropical to warm temperate species unlikely to have survived its first winter here. The shallow pond in Central Park does have a connection to the Fraser River, but we are fortunate that the Fraser lacks appropriate habitat for Blotched Snakeheads. BC’s high-energy cold water streams would be inhospitable to the Blotched Snakehead, and in that specific pond in Burnaby, the snakehead’s prey-base only included exotic fishes – carp, goldfish, bullhead catfish and golden fathead minnows (and maybe a duckling or two).

The Pacu (Piaractus cf. P. brachypomus) from Green lake in Nanaimo (the black scale bar is 2.54 cm), and an albino Oscar (Astronotus ocellatus) from Chemainus (now cataloged in the RBCM ichthyology collection (RBCM 011-00212-001).

As of December 18, 2012, laws have changed, fines are in place, and all members of the family Channidae are illegal to import possess, breed, and transport in British Columbia. Yes this includes some of the smaller tropical species, but I assume the intention of the family-wide ban is to prevent importation of young Northern Snakeheads under false “tropical” names. Even today, Gars (Family Lepisosteidae) regularly get imported under false names even though they are banned by toothless federal regulations. Given that snakeheads are fairly rare in the pet trade, the new provincial legislation will have its heaviest impact on the life-food trade.

The silver-lining to this story is that only one snakehead was dumped into the pond in Burnaby, and it could not reproduce alone. Most other exotic species incursions are not this easy to eliminate. We also are lucky most pet owners are responsible and do not simply abandon their pets, but those few that do, burden society with the significant cleanup expense (remember UVIC’s bunnies?). For many species, we could spend millions and never win the battle.

References not linked to PDFs:

Fuller, Nico & Williams. 1999. Nonindiginous Fishes Introduced into Inland Waters of the United States. American Fisheries Society Special Publication 27, American Fisheries Society, Bethesda, U.S.A. 613 p.

Yamamoto & Tagawa. 2000 Hawaii’s native and exotic freshwater animals. Mutual Publishing, Honolulu, Hawaii. 200 p.