Fixation and Preservation

Occasionally I get emails asking how to ‘pickle’ vertebrate specimens. I thought I would lay out a simple recipe that should do in most cases. I am assuming here that the animal already has been euthanised or was found dead.

The ‘pickling’ process is divided into three parts:

1) fixation

2) rinse

3) preservation

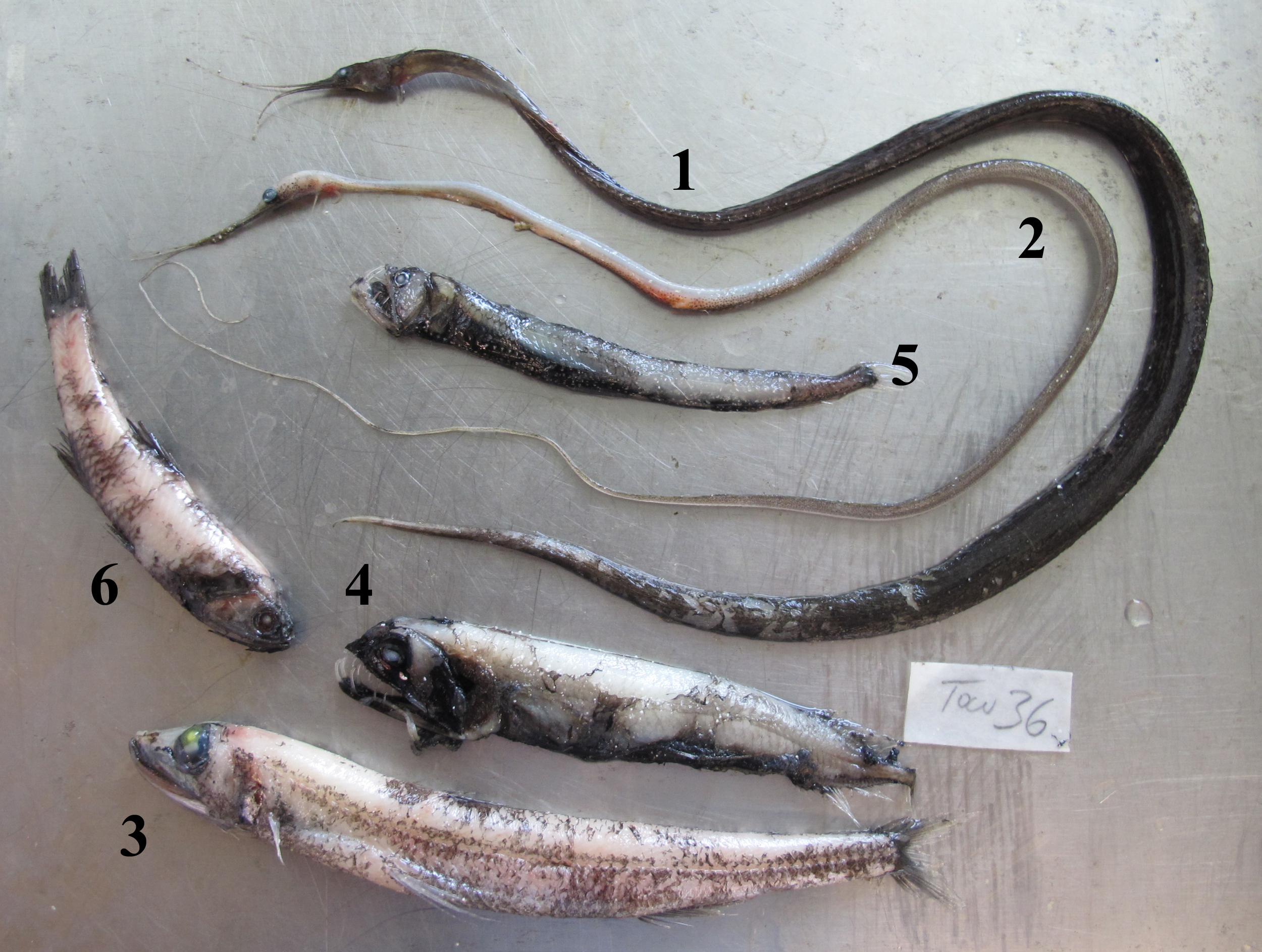

A frozen mixed bag of deep-sea fishes from sample 36, October 23rd, 2006, 50°01.0’N; 128°18.8’W and 1203 meters average depth.

A frozen mixed bag of deep-sea fishes from sample 36, October 23rd, 2006, 50°01.0’N; 128°18.8’W and 1203 meters average depth.

Thawed fishes from sample 36 – 1) Avocet Snipe Eel, 2) Slender Snipe Eel, 3) Northern Pearleye, 4) Shiny Loosejaw, 5) Pacific Viperfish, and 6) a possible Garnet Lanternfish – it has red photophores.

Thawed fishes from sample 36 – 1) Avocet Snipe Eel, 2) Slender Snipe Eel, 3) Northern Pearleye, 4) Shiny Loosejaw, 5) Pacific Viperfish, and 6) a possible Garnet Lanternfish – it has red photophores.

1) Fixation is the chemical process where the animal is locked in as life-like a state as possible (i.e., embalming). You cannot beat Formaldehyde for this part of the process. Formaldehyde is a small molecule that penetrates a specimen and fixes it in a stiff rubbery state. Immerse the animal you want fixed into 10% Formaldehyde (it is not an exact science – you can eye-ball the percentage). If the specimen is really oily (i.e., a sucker), you may want to use a more concentrated solution of Formaldehyde (maybe around 15%?).

Note: If you want tissue samples for molecular research, take tissue samples before you fix the entire carcass. Tissue samples for molecular research can be fixed in 99% ethanol in small vials, and keep the vials on ice for long term storage.

Fishes in Formaldehyde in a ziplock bag. Formaldehyde is clear and colourless, so label the sample to warn people. The cloudy state here is from fish slime in the water. There would be far more slime if the bag contained a Northern Pike from a gill net.

Fishes in Formaldehyde in a ziplock bag. Formaldehyde is clear and colourless, so label the sample to warn people. The cloudy state here is from fish slime in the water. There would be far more slime if the bag contained a Northern Pike from a gill net.

Large animals need to be injected with Formaldehyde every 3-5 cm of length to make sure all tissues fix before they rot. Something as large as a shark or sturgeon needs injections all over the body. You can also slit open the body cavity to allow Formaldehyde to diffuse throughout the gut. Make sure you slit open or inject the correct side of the animal for the respective science – ichthyologists leave the left side of a fish intact and only cut or inject the right side. It’s a tradition.

Snakes, turtles, crocodilia and lizards have a skin that is really impermeable to Formaldehyde – so I inject them to make sure the animal is properly pickled. I also use a fine needle to prick holes in the tails of snakes and tails and legs of turtles and lizards to make sure Formaldehyde diffuses everywhere. The mouth can be propped open with a bit of wood to make sure plenty of Formaldehyde soaks into the head end.

I once opened a jar with a pickled rattlesnake, and as I pulled the snake out, it strained through my fingers. Whoever fixed that snake had not injected Formaldehyde, and it had rotted in its own skin. Only the tail and head were fixed because Formaldehyde infiltrated through the mouth and cloaca.

Animals are left to soak in Formaldehyde for a week to two weeks. However, Formaldehyde is nasty to work with for regular specimen handling (see the MSDS), and so once fixed, we want to remove as much residual Formaldehyde as possible.

You can use Ethanol as a fixative instead of formaldehyde, but it is not as effective and specimens degrade far sooner.

2) Rinse the specimen. Dispose of the waste Formaldehyde responsibly (not down the drain) – your local chemical disposal depot will know what to do. The animal(s) can be rinsed for at least a week in water – and you should change the water a few times during the week to rinse out as much residual Formaldehyde as possible.

Specimens rinsing in water – doesn’t look all that different really and why warning labels are essential.

Specimens rinsing in water – doesn’t look all that different really and why warning labels are essential.

3) Preservation is the long term storage of the animal – and this is the simplest part of the process. Just dunk the animal in Ethanol or Isopropanol, your choice. We store specimens in 70% Ethanol, or 60% Isopropanol.

Some prefer Isopropanol since there is less risk of lab techs mixing it with pop or juice to smooth out the work day. Yes, lab-grade Ethanol has been mixed for human consumption – I know someone who mixed lab Ethanol with TANG – yikes. Have a look at the list of impurities sometimes found in lab grade Ethanol. Then if you still want to drink alcohol, go to your local liquor store, it is far safer.

One time, a colleague of mine (and I ) were sampling for salmonids for a contract he had, and accidentally caught something that looked like a Bull Trout (Salvelinus confluentus). His permit did not cover that species. We had to fix and preserve that fish to make sure we had the identification correct (to “clear” our name) – and since we were only doing catch and release electrofishing – we had no fixative or preservatives with us. We went into the nearest town and bought the strongest vodka we could find. Worked like a charm – and the fish proved to be a juvenile Lake Trout (Salvelinus namaycush) (whew).

Preserved specimens should be stored in a vat or jar with a good seal (a gasket, not the mammal). Over the years, alcohol evaporates and so you will have to change the alcohol. If you simply top up the alcohol with the same percentage, the alcohol content eventually drops. It is best to just swap out all the alcohol in a jar to be sure you have the right concentration. Alcohol also leaches out fats, and so oily specimens need more frequent alcohol changes to keep them from degrading.

Specimens in jar of alcohol, awaiting identification and segregation into species-specific jars for final storage in the RBCM collection.

Specimens in jar of alcohol, awaiting identification and segregation into species-specific jars for final storage in the RBCM collection.

With proper care, specimens will last hundreds of years – the Royal BC Museum has an Adder from the UK that was collected in 1835, and it still looks perfect – minus the colour. One thing you can’t prevent is the loss of colour. All ‘pickled’ specimens turn a pale peanut butter yellow-brown colour. Melanin is preserved for a long time such that dark spots and stripes will remain, but structural colours (the iridescent colours in fishes) and other pigments will be lost. I have seen alcohol turn pale pink a few weeks after a formaldehyde-fixed breeding male Jewel Cichlid was put in a jar. I heard that someone in Russia had developed a concoction that would keep colour in fixed specimens, but I dread to think what that mixture contained. Dark pigment will stay longer in total darkness – which is why we turn off lights to collection areas when not in use. Fixed and preserved specimens will fade with excess light exposure.

I hope this helps to answer some questions on specimen fixation and preservation. The technique is more of an art form than exact science because every specimen pickles differently. Sometimes you just have to wing-it and leave the specimen longer, or in stronger formaldehyde, but the basic formula above will fix most vertebrates.

Western Blacknose Dace (Rhinichthys obtusus) collected in 2002, with slightly yellowed alcohol.

Western Blacknose Dace (Rhinichthys obtusus) collected in 2002, with slightly yellowed alcohol.