Passenger Pigeon from the Royal BC Museum Collection; photo by G. Hanke

Passenger Pigeon from the Royal BC Museum Collection; photo by G. Hanke

The last wild Passenger Pigeon was shot in 1900 by an Ohio boy wielding a BB gun. September 1st 1914, Martha died. With her death in Cincinnati, Ectopistes migratorius (the Passenger Pigeon) went extinct. This extinction was overshadowed by events elsewhere: WWI had just started.

Passenger Pigeons were superabundant when Europeans arrived in North America. As colonists spread, Passenger Pigeons were killed for meat, medicinal products, pig food, for feathers, and caught live for target practice. Nestlings represented easy targets, and were simply knocked out of their nests, or trees containing nests were cut down. Sometimes trees were burned and nestlings roasted in place. Alcohol soaked grain, bait birds, and large nets were used to trap dozens to a few thousand adult birds at a time. Millions were shot.

The ultimate demise of the species was from industrial slaughter continuing until populations dropped to levels where nesting colonies failed. Courtship and reproduction was successful only when large numbers gathered. With few birds remaining, breeding colonies failed, and the few birds in captive breeding programmes represented a futile effort. Along with this reproductive constraint, conservation efforts failed to convince politicians to protect the species and conservation laws were largely ignored.

Passenger Pigeon from the Royal BC Museum Collection; photo by G. Hanke

The Carolina Parakeet (Conuropsis carolinensis) also shared the iron sights with Passenger Pigeons. Carolina Parakeets also were common when Europeans landed in North America, but parakeet populations sequentially collapsed as colonists rolled westward. By 1900, Carolina Parakeets were restricted to swamps of central Florida.

Many were silenced for the fashion industry, pest control, some were kept as pets, and deforestation sealed their fate across much of North America. Carolina Parakeets also tended to land near dead or dying birds. Such congregations made wholesale slaughter far easier. The final extinction happened rapidly: breeding flocks were present in 1896, but had vanished about 8 years later. Some think the last flocks of Carolina Parakeets contracted diseases from poultry. The last captive bird died in Cincinnati, February 21, 1918. This extinction also was overshadowed by events elsewhere: WWI was nearing its end.

North American colonists decided the fate of both bird species and regardless of conservation efforts, tactics didn’t change on a local level when these birds became scarce.

Entrenched tactics also were characteristic of the whaling industry. When one species became scarce, we targeted another. British Columbia’s whaling stations closed during my lifetime (1967) – ending an industry which took several species to the brink of extinction. Some populations were wiped out. Grey Whales (Eschrichtius robustus) are only now repopulating the Atlantic. Illegal wholesale slaughter in the Bering Sea, Gulf of Alaska, and Sea Okhotsk in the mid-1960s1 may have pushed North Pacific Right Whales over the tipping point. Like small flocks of Passenger Pigeons, reproductive failure could be their end. Some say only 8 females remain – a few ship strikes, some natural mortality, and the species would be gone.

Like our southern neighbours with the Passenger Pigeon, British Columbians slaughtered Basking Sharks (Cetorhinus maximus) for sport, out of ignorance, and the misguided effort to control a pest. Basking Sharks were vilified because of their interference with salmon fisheries, and people jumped at the chance to kill these passive planktivores. This coordinated slaughter ended by 19702, with Basking Sharks all but extirpated from British Columbia waters.

Basking Shark; http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Cetorhinus_maximus_by_greg_skomal.JPG

Perhaps the Spotted Owl (Strix occidentalis) is next to go. British Columbia is down to its last few breeding pairs. With habitat loss and ecological replacement by Barred Owls (Strix varia), why do we even expect this species to survive let alone recover? Barred Owls are becoming increasingly common, and I expect that the Spotted Owl will disappear from Canada, maybe even go extinct, well before I acquiesce to entropy.

Spotted Owl; http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Northern_Spotted_Owl.USFWS-thumb.jpg

The Sharp-tailed Snake (Contia tenuis) is tiny and harmless, yet may vanish from British Columbia out of ignorance and urbanisation rather than active persecution. Like Spotted Owls at night, Sharp-tailed Snakes go unseen but compete with us for hotly-contested real estate. In south western British Columbia, farms and wild habitat are rapidly being replaced by urban sprawl and industry. It is no surprise that road kills account for most recent Sharp-tail specimens. Will these snakes exist like the Passenger Pigeon, only as specimens in a museum collection?

Sage Grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus) and White-tailed Jackrabbits (Lepus townsendii) no longer breed in BC. How many noticed their disappearance? Could the Rocky Mountain Tailed-frog (Ascaphus montanus) or Coastal Giant Salamander (Dicamptodon tenebrosus) be next to vanish from BC? Both have a restricted range and could be decimated by careless development or industrial accidents.

Coastal Giant Salamander; http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Dicamptodon_tenebrosus_2.JPG

Who mourned the species-pair of Dragon Lake Whitefish? Fisheries researchers poisoned the only lake containing these whitefish, before these fishes were known to science. Why was the lake treated with toxaphene? To wipe out the native fauna and develop a sport fishery.

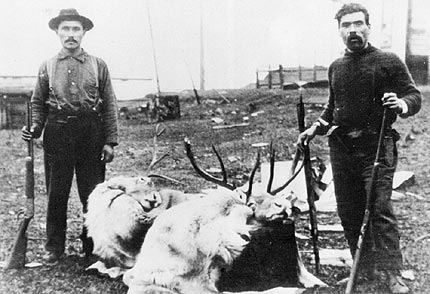

The last few Dawson’s Caribou; Royal BC Museum and Archives

Who remembers the Dawson’s Caribou, the subspecies of Rangifer tarandus from Haida Gwaii? Three of the last four were shot. Extinction followed shortly after: caribou cannot reproduce asexually.

Humans have been called the most effective and selfish predator of all3. We are not eating every species to extinction, but we are consuming natural resources at a staggering rate. In BC, concerted efforts have gone into protecting the Vancouver Island Marmot and Spotted Owl. Leopard Frogs are bred and released to try bolster their populations. Habitat protection and restoration continues, with many projects underway to undo some of the damage we have caused. We won’t be the next extinction, but we are the only species that could go extinct and improve the ecology of the planet4.

Northern Leopard Frog (Delta Marsh, Manitoba); photo by G. Hanke

Last year there was some good news for marine biologists, two different North Pacific Right Whales were sighted along the BC coastline5, as well as a Basking Shark. Let’s hope more follow, and populations rebound.

It is too late for the Passenger Pigeon, but I wonder what will survive the next 100 years?

My neighbour Russell; photo by G. Hanke.

References:

1) Ivashchenko, Y.V. & P.J. Clapham. 2012. Soviet catches of bowhead (Balaena mysticetus) and right whales (Eubalaena japonica) in the North Pacific and Okhotsk Sea. Endangered Species Research 18: 201–217.

2) Wallace, S. & B. Gisborne. 2006. Basking Sharks, the slaughter of BC’s gentle giants. New Star Books Ltd., Vancouver. 92 p.

3) Scott, W.B. & E.J. Crossman. 1973. Freshwater fishes of Canada. Bulletin of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada 184: 1-966.

4) Weisman, A. 2007. The World Without Us. Harper Collins Press, Toronto. 416 p.

5) Ford, J.K. 2014. Marine Mammals of British Columbia. Royal BC Museum Handbook Series, Victoria. in press.

See also:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Passenger_Pigeon

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carolina_Parakeet