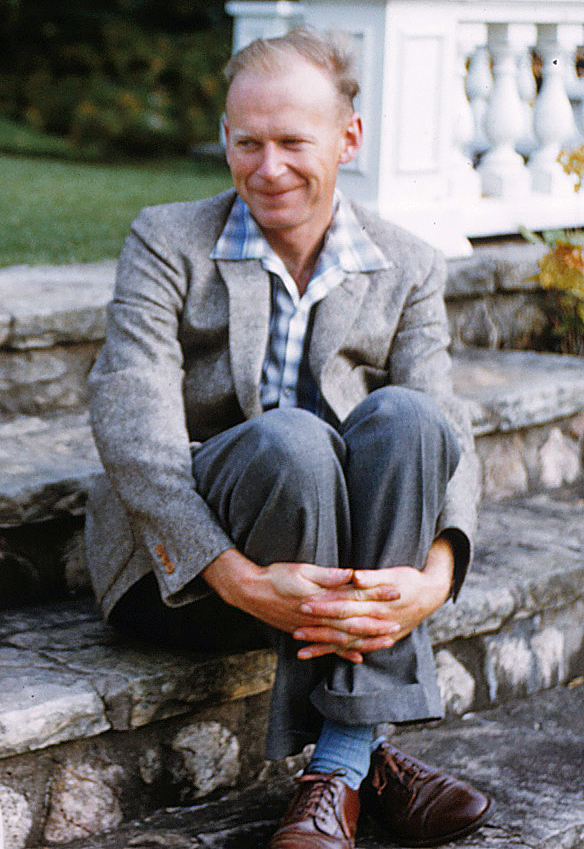

Jim Grant, biologist, educator, and mentor. September 1958. Photo: Phil Jones

Back in 2009, I was fortunate to receive the Bruce Naylor Award from the Alliance of Natural History Museums of Canada. This prize is for contributions to museum-based natural history research in Canada. In my “thank-you” comments (27 October 2009, Houses of Parliament, Ottawa), I wanted to emphasize a critical function of a museum biologist’s life – helping a kid; passing the torch. I also wanted to make the talk personal. Leaving out the non-essential parts of the speech, this is what I said:

“Jim Grant was an extraordinary naturalist and professional entomologist in BC’s Okanagan Valley, where I grew up. He was a great friend of my father and, from an early age, I considered him a friend and mentor. His encouragement was one of the main reasons that I became fascinated by insects in the late 1950s. He had the delightful habit of dropping by our house in Penticton with entomological treasures. Once he brought me the first Monarch butterfly caterpillar I had ever seen. In BC this is a very rare species and, to a young BC insect enthusiast, this iconic caterpillar was pure gold. Jim left it at our doorstep one summer day.

I raised that butterfly patiently and my Dad and I photographed it through the various stages of its growth. I still use some of those pictures in slide shows today. A camping holiday intervened during the pupal stage and I carried the jar the whole way. To my relief, the adult emerged the day after we got home. Then came the big moral dilemma – to let the butterfly go or put it in my collection. I had grown attached to the insect over the weeks that I’d raised it; killing it seemed a really bad idea. And Monarchs were rare in the Okanagan, so letting it go was sensible. But I knew I would probably never catch another, and I desperately wanted that specimen. In the end, the collecting urge triumphed. With considerable guilt, I carefully added the butterfly to my collection. And, as Jim taught me was critical for all my specimens, I made a label listing all the collection information and pinned it with the butterfly.

Now before coming to the Royal BC Museum, I was curator of the Spencer Entomological Museum at the University of BC. Dr. Walter Lazorko, a retired psychiatrist and expert amateur beetle researcher, frequently came to work in the collection. Walter was a tall, distinguished European gentleman, always in suit and tie. He was a character, usually rather morose and pessimistic. He had been through a lot. Among other things, in the chaos of the spring of 1945 he had smuggled his huge beetle collection across war-torn Europe from the Ukraine to Austria and, from there, brought it to Canada. An amazing feat! One day, while we were lamenting the state of amateur entomology in BC, he started talking about his pal, Jim Grant, my old Okanagan mentor.

“There should be more people like Jim”, said Walter, “He always encouraged kids – there would be more young entomologists if more of us were like Jim!”

Walter could get excited in a gloomy sort of way. “Why, he went on, “once when I was on a collecting trip with Jim at Penticton, way back about 1960, we found a Monarch butterfly larva on a milkweed plant…. Very rare. Jim said, ‘I know a young boy who would love to have this.’ Jim and I drove a long way up to this boy’s house but he wasn’t home, so we left the caterpillar in a bag attached to the door handle.”

Walter’s story stunned me. The caterpillar on the door was a family legend. “Walter”, I said softly, “that young boy was me.” Walter was even more flabbergasted – almost disbelieving. After a long silence, tears ran down his cheeks and he said with conviction, “You see, then you were a small boy and now you’re an entomologist — that’s what Jim did for you!” Of course, an exact cause and effect is a little far-fetched, but both incidents – the caterpillar on the door and the lunchtime conversation in the museum – have stayed with me.

Later, when I was president of the Entomological Society of BC, I helped create an award for the best graduate student paper delivered at our annual meeting. We call it the James Grant Award in honour of Jim’s dedication to inspiring kids, to passing the torch.

All this is to say that a small act can go a long way in stimulating the quest for knowledge in children and adults alike. I hope that we all can do this, more and more, in our own museum work.”

Rob Cannings (centre) receiving the Bruce Naylor Award, 27 October 2009. Left, Pauline Rafferty, CEO, Royal BC Museum and President, Alliance of Natural History Museums of Canada; right, Bill Greenlaw, CEO, Nova Scotia Museum and Chair of the Awards Committee.

Rob Cannings (right) teaching a kid (Darren Copley, left) how to collect dragonfly larvae in the field (Prince Rupert, BC, 2005) Photo: Claudia Copley