I’m filing this entry under the heading of “Who Knew”? I often find myself thinking this while examining some of our archival records, and I had the same reaction when I opened an email from Angie Thomas. Angie works for the Museum of the Mountain Man, (MMM) in Pinedale, Wyoming – an institution which is dedicated to presenting the history of the Mountain Man and the Western fur trade.

I wasn’t quite sure what a Mountain Man was, but thanks to Angie, one of the museum’s associated historians Jim Hardee, and Wikipedia I now understand a little more about their significance in the early fur trade history of the Rockies. If you call someone a “Mountain Man” because they are grizzled, weather-beaten and perhaps a little rank, you are not too far off the mark.

The Mountain Men were traders, trappers and explorers, many of whom worked independently of the big fur trade companies such as the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) and the North West Company. They lived a rugged life in and around the Rocky Mountains, trading with the local First Nations, and the fur companies, primarily between 1810 and 1840. For a romantic view of the life of one of the later Mountain Men, you could watch the film Jeremiah Johnson, starring Robert Redford. (While Jeremiah is a fictional character, some of the events of the film are based on the life of a real-life Mountain man – John “Liver-Eating” Johnston.)

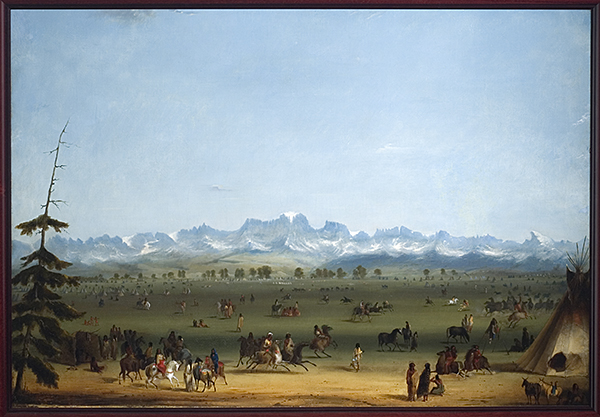

Back to fur trade history. Once a year American traders, trappers and First Nations gathered at a giant trade fair, known as a “Rendezvous,” at a pre-arranged spot, often in the territory of the Snake Indians near Green River in Wyoming. The painting below is a record of the 1837 Rendezvous by Alfred Jacob Miller.

“But,” you ask, “What is the connection to B.C. history?” The answer lies in the ambitions of the Hudson’s Bay Company, which wanted to extend its interests even further south and east in the vast Oregon Country. (Keep in mind that the border between Canada and the U.S. in the West wasn’t settled until 1846. In the 1830s, the area west of the continental divide was jointly occupied by British and American traders).

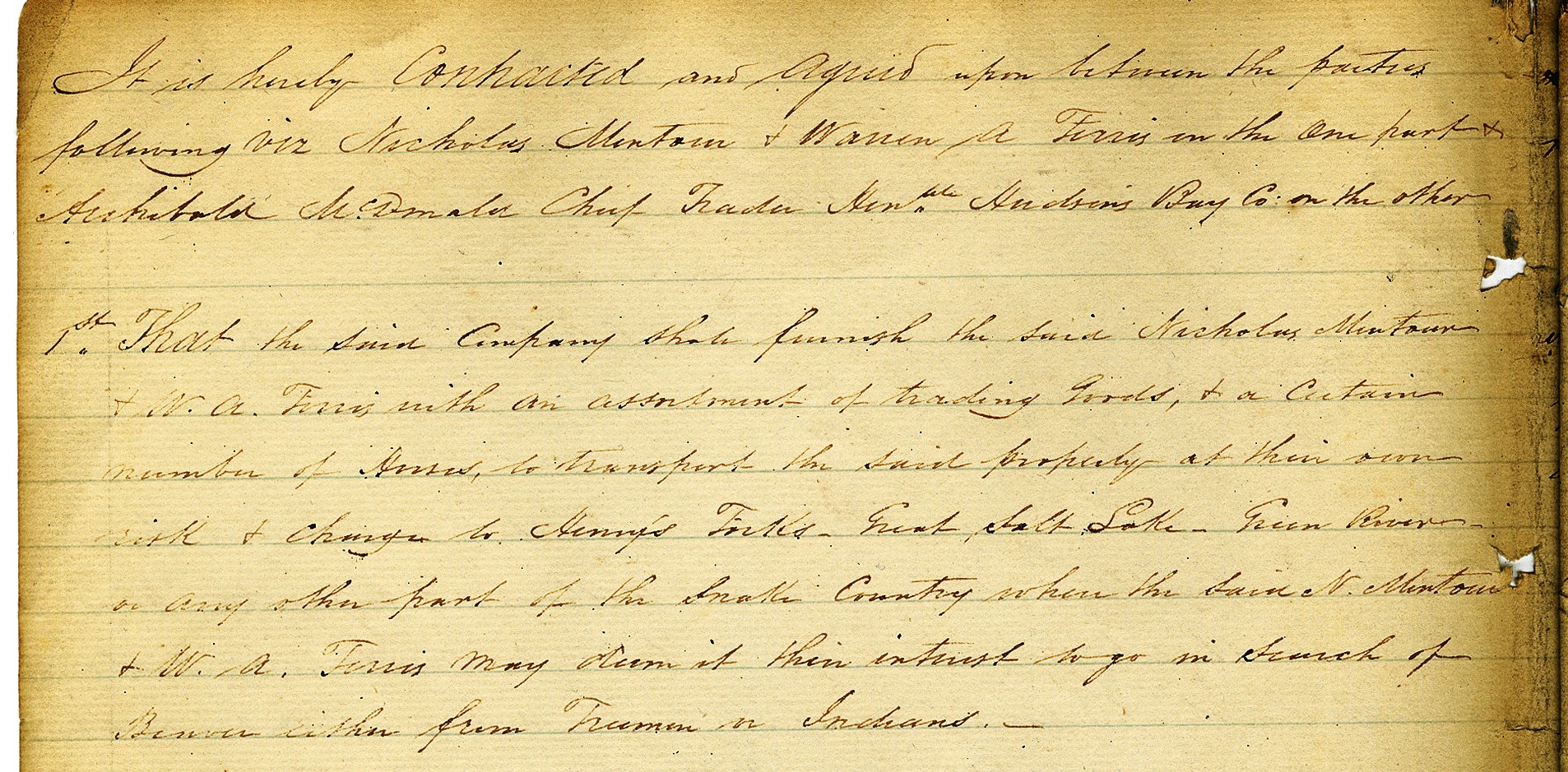

The MMM came calling because they were about to publish an article by Scott Walker about an American Mountain Man named Warren Ferris, and his role as an agent of the HBC. One of the key documents relating to Ferris is held here at the B.C. Archives and they needed a digital copy.

In 1834, HBC Chief Trader Archibald McDonald wrote in his letterbook that Ferris, and his partner Nicholas Montour (an HBC employee) were authorized to take “an assortment of trading goods, and a certain number of asses, to transport the said property at their own risk and charge to Henry’s Forks, Great Salt Lake, Green River or any other part of the Snake Country….when [they] …deem it in their interest to go in search of Beaver, either from Freemen [independent trappers] or Indians.”

Ferris was chosen because he was considered a skilled trader, was an American by birth, and had formerly worked for the American Fur Company. The aims of the HBC were relatively simple: make as much profit on trade goods as possible, undercut the American fur trade companies, and strip the area of fur before the joint occupancy of the territory ended and their economic empire shrank. There’s no proof that Ferris made it to the 1834 Rendezvous, but he did work his way further south during the winter, trading as he went.

More “Who Knew?” moments came when I looked at the table of trade goods that were supplied to Ferris and Montour by the HBC. The original document is in Winnipeg at the HBC Archives, but Walker carefully transcribed it as an appendix to his article, with notes. The goods are a fascinating combination of practical supplies, small luxuries, and items designed specifically for trade with the First Nations population. The two traders headed south with almost a ton of goods, from beads and blankets to 210 pounds of tobacco and 45 gallons of whiskey. For their own bookkeeping, the list itemizes two quires of paper, a memo book, one (!) pencil and one penknife.

Ferris’s tour of duty as an HBC agent ended the next summer when he had to return home to New York State to sort out urgent family matters. He never returned to the Rocky Mountains. The HBC continued attempts to “infiltrate” the American Rendezvous system, but were forced to pull back their trading operations after the international boundary line was set at the 49th parallel in 1846.

It was a pleasure to be able to help the Museum of the Mountain Man with their research, and if I’m ever near Pinedale, Wyoming I’ll be stopping in to find out more. For those who can’t get to Wyoming, here’s a good source of information: http://www.thefurtrapper.com/rendezvous.htm