A few months ago, a box of archival records that had been requested for access was transferred to the Royal BC Museum paper conservation lab. These documents were part of the Archibald Menzies fonds, a small collection of records and belongings related to Archibald Menzies (1754–1842), a Scottish surgeon and naturalist who accompanied Captain George Vancouver aboard the HMS Discovery in 1791–95.

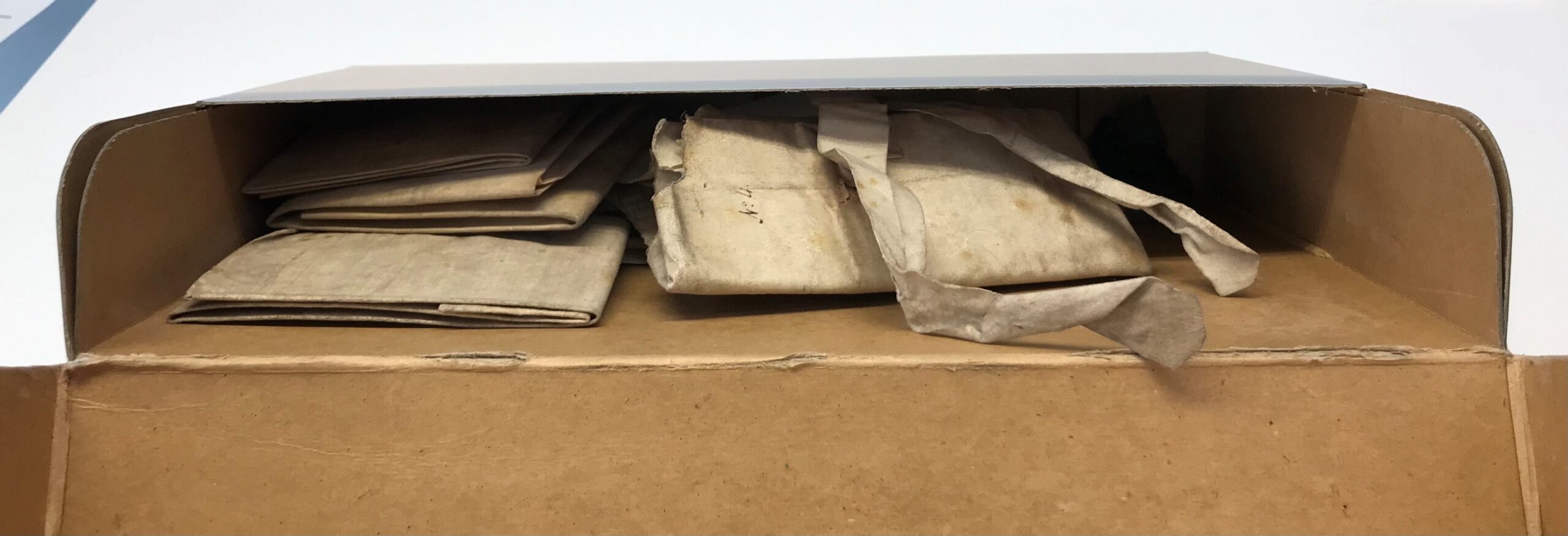

The documents in this box were mostly parchment and had been folded several times in the past, then piled into a box for storage. Upon retrieving the box, the archivist realised that none of these documents were easy to open. The parchment was hard and inflexible, suggesting that any attempt to forcibly flatten out the records might lead to damage. When problems like this arise, these materials are diverted to our conservation team for assessment and remedy.

So, how can we convince parchment to relax, open up and share its hidden secrets? First, we need to understand where it’s coming from.

The Nature of Parchment

Parchment is made from animal skin—usually that of a calf, sheep or goat. The skins are removed from the animal, dehaired and defleshed, and then treated with a lime or other alkali solution. After liming, the skin is dried under tension, and in some cases, surface treatments are carried out to make it more suitable to receive inks and paints. Before the invention of paper, parchment was a common writing support in Europe and parts of the Middle East. It continued to be used as such for several centuries after papermaking became popular and widespread.

Parchment is very sensitive to moisture and heat. This means that when water is present, the parchment will expand and absorb moisture. When conditions become warm and dry, the parchment will shrink and release moisture. Over long stretches of time, these cycles of shrinking and expanding cause the parchment to deteriorate, becoming distorted and hard.

Relax and Unfold

The parchment documents in this collection were tightly folded, and attempts to open them were met with strong resistance. Forcing them open could have potentially led to cracks, breaks and losses in the document; however, leaving them as they were meant that no one could read them.

To open these documents without incurring damage and loss, we needed them to relax. This state of inner peace was achieved with the careful introduction of moisture. Since parchment is so sensitive to moisture, the use of moisture to treat deteriorated parchment might seem counterintuitive; however, in the case of this treatment, moisture is delivered in the form of water vapour (never liquid water), and it was delivered with control.

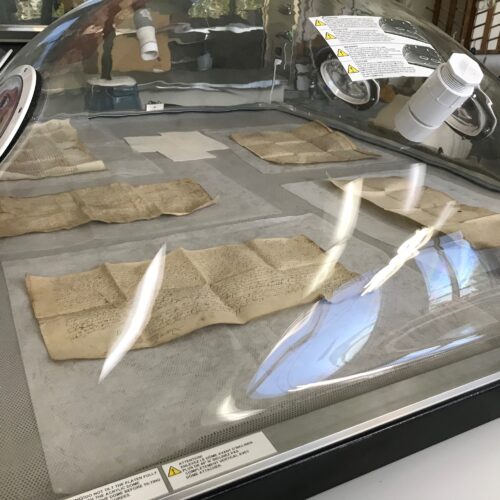

The tightly folded documents were placed in an environmental chamber where the relative humidity (RH) could be raised using an ultrasonic humidifier. The RH levels were monitored throughout this treatment using a hygrometer placed in the chamber. Slowly, over a period of approximately two hours, the documents were unfolded bit by bit, until they were relaxed enough to fall completely open.

Once the documents had fully revealed themselves, they were placed under very gentle pressure between felt pads to ensure they dried flat.

A New Home

Now that these documents are open for viewing, they will be stored flat. They have been transferred to a flat storage box with custom padded trays for two of the documents, with seals and cords attached, ready for the next researcher.